Enrico Bonadio: What is the relationship between street art and the law? In his latest book ‘A Philosophy Guide to Street Art and the Law’ Andrea Baldini argues that street art has a constitutive relationship with the law. The first lines of Andrea's book – ‘I fought the law, and the law swanned’ – introduce the reader to the relationship between art and law with a citation that adapts the lyrics of a song by the British punk band The Clash – the story of a young man who ends up in jail after committing armed robbery.

Andrea then proposes an interesting analogy: the law swans in the street art world, and it does so in an inconsistent and causal way. On the one hand, the full weight of justice punishes street artists and graffiti writers that paint illegally because of laws that treat them in the very same way members of organised crimes are treated. On the other hand, our societies often glorify the vandalism of certain artists, especially the most famous ones.

This is the well-known ‘street art / vandalism’ dichotomy or paradox. Yet, Andrea believes that this is actually not a dichotomy – let alone a paradox. He sees the relationship between street art and vandalism as not incidental. The various forms of art placed in the street – as Andrea puts it – are both ‘art’ and ‘vandalism’. In other words, vandalism is a technique that street artists and graffiti writers use to imbue their creations with meaning and subversive value. Infringing the law constitutes the very meaning of the street artwork or the graffiti piece. Andrea stresses in his book that subversiveness and illegality are the main structural features of these forms of art.

Subversiveness is a theme that also pervades the second half of Andrea's book, which focuses on the relationship between street art and graffiti and copyright. Andrea notes that it is because of the subversive nature of these forms of art that copyright is not an appropriate legal tool to protect artists from corporate misappropriation. Contrary to my own opinion on this subject, for Andrea copyright is capable of corrupting, destabilising and jeopardising the very heart of street art and graffiti. According to Andrea, copyright has the power of turning everything it touches into a ‘hot commodity’. As mentioned, I have an opposing view, but I welcome robust academic debate, and I hope that this critical discussion will stimulate further research on this fascinating area at the intersection between subcultural creativity and intellectual property laws.

Andrea will now present his book, with critical responses from Susan Hansen, Sabina Andron, and members of the audience.

Andrea Baldini: Why do people get interested in academic discussions on street art? We all come from very different backgrounds in terms of disciplines. Interdisciplinarity is largely a myth – it's usually an illusion – but somehow street art is capable of violating boundaries, even when we get to academic discussion, because it's very difficult to actually understand the complexities of the phenomenon from only one point of view.

This book is about how the law relates to street art. In it, I argue that street art has a constitutive relationship with the law – I think that it is not accidental. But, what is the link binding law and street art together? Is street art necessarily illegal?

In the book, I build on Alison Young'saccount in her book Street Art, Public City to introduce a distinction between illicitness and illegality – where illicitness is basically a matter of violating social norms and customs, and illegality is actually a notion that relates to violating a positive law. I use an example in the book about the illicitness of Hawaiian pizza in Naples. But nobody goes to jail for that.

Illegality has to do with positive laws. Something becomes a token of illegality when a judge decides it. This is very important. So, illegality is not a property, strictly saying, that inheres in actions – it is actually something that is conferred by the action of a judge. If you kill somebody, you haven't done something that is illegal per se, it is something that is characterised as illegal by a judge.

There is a further way of distinguishing the question. On the one hand, you could say that illegality is a necessary condition for street art, on the other, that it is a sufficient condition for street art. So, when you talk about a necessary condition, you want to say that you can find X feature or property in ALL genuine examples of street art. However, this view has counterintuitive implications at a conceptual level and in terms of demarcation – insofar as many accept at least some legal works as street art. In the second sense, one may say instead that the property of ‘being illegal’ is a sufficient condition for an artwork to be street art. As a sufficient condition, illegality need not be present in all genuine cases of street art, but it provides us with enough ground for considering an artwork as street art. For instance, Andrea Brighenti says that illegality is the zero degree of street art – or graffiti. Following from this claim, one could say that there are many borderline cases – legal artworks, commissioned artworks, etc. – whose identity as street artworks is contested. However, there are some core cases – illegal artworks – that straightforwardly qualify as genuine street art. Their illegality is sufficient for making them street art.

I also believe that this second view is actually false: there are cases of artworks that, although illegal, do not qualify as street art. In the book, I use the example of street based work by Fauxreel – who did a series of giant wheatpastes in Toronto that looked like street art but that turned out to be part of an illegal advertising campaign for Vespa. Now if you want to say illegality is a sufficient condition, then you have to tell me that this is actually street art. But a lot of people were critical of Fauxreel's actions, and many refused to consider it to be street art, despite the fact that this campaign was illegal.

So, is illegality a necessary or sufficient condition for an artwork to be street art? In the book, I argue that illegality is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for an artwork to be street art. However, ‘being illegal’ does function as a ground for the social holistic property of ‘being subversive’.

I define street art as an essentially subversive art kind. An art kind is basically a set of artworks that share a particular value. My argument is that the value that all street art works share is their subversive value. And the subversive value of street art is a function of its capacity to question acceptable uses of public spaces. The idea is that there are certain social norms, laws, habits, that regulate what you can do, and what you can't do, in public spaces. For instance, you can't walk outside naked, you can't paint on the street. But you can do other things. Today, the set of norms that regulate public spaces gives priority to advertising transforming public space into a forum for economic transaction. I call this the corporate regime of visibility, which street art challenges.

Susan Hansen: As Andrea mentioned, one of the really neat things about scholarship on street art and graffiti is that it is interdisciplinary. Everybody on the panel today comes from a different disciplinary background – which I think can be quite productive – but I'm not sure that I agree with Andrea when he says we are speaking the same language, because I think sometimes we are not. While interdisciplinarity can lead to complementarity, I think it may also be productive to explore some of our differences.

With our divergent backgrounds in law, philosophy, anthropology, and architectural history we bring some of these differences to the table tonight. My own background is in art history and social psychology. My work is grounded in ethnomethodology – a form of sociology with a focus on people's own mundane sense-making methods, rather than top down forms of categorisation and analysis.

I’ve been trying for the last decade or so to apply some of these ethnomethodological principles to the analysis of graffiti and street art, which are obviously primarily visual, and often presented as works of art. We're used to seeing works of art in gallery space as discrete objects produced by one person, and that's also the way that we tend to reproduce images of street art on Instagram, or in beautiful books. These usually feature photographs that capture artworks shortly after they were painted. But that is a different thing from street art as it exists on the walls of our cities. If you look at street art the way that ordinary people passing that wall on their way to work every morning look at it, you will see it instead as part of a living wall – as a changing surface that is not the result of single authorship. Unlike art in galleries, multiple people contribute their thoughts to our city walls, and if you have a lipstick or a pen in your pocket you can make your own mark. This is very different from art as it exists in museums.

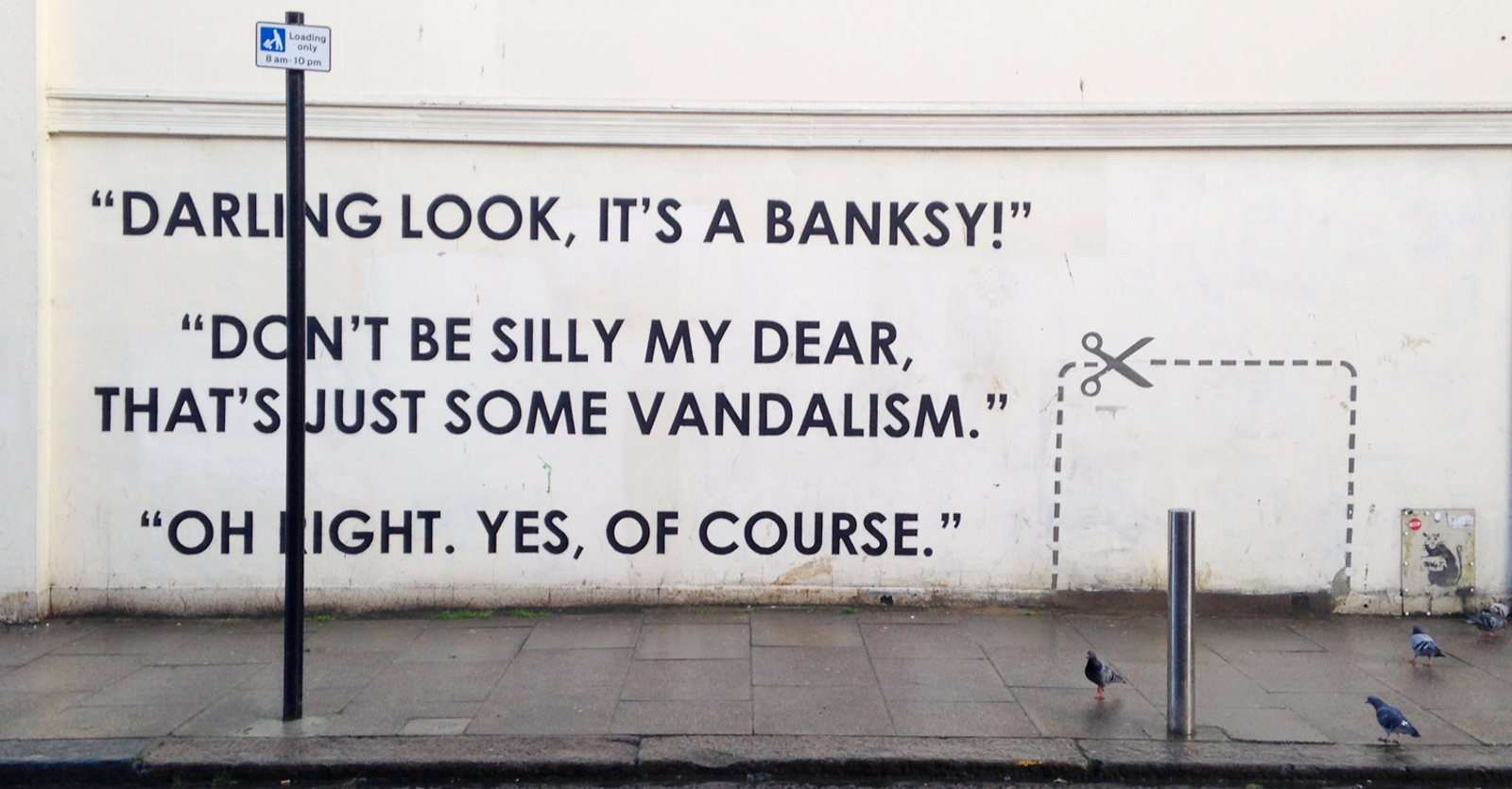

This is a still from a 5-year longitudinal photo-documentation project that I thought might be relevant to our discussion today. We can see the distinction being drawn here by the artist Mobstr between what is received as ‘a Banksy’ versus ‘vandalism’ or graffiti. This draws attention to the hierarchy of aesthetic worth that guides our very practices of looking when we're talking about graffiti and street art. This text arrests the viewer with an exclamation and an injunction – ‘Darling look, it's a Banksy!’, that is, it's worth looking at because it's street art. But this is followed by the dismissive and downgrading retort, ‘Don't be silly my dear that's just some vandalism’. So, this is a satirically banal commentary on our mundane evaluation of the status or worth of street art, that critiques the objectification and commodification of street art that Andrea just alluded to. Here ‘a Banksy’ (street art) is positioned as something that's worth exclaiming over and looking at and ‘some vandalism’ (graffiti) is the stuff that's not worthy of viewers' attention.

The main point here is that art on our city walls is temporally unfolding and permanently unfinished, which makes it a slightly different kind of thing that Andrea and I are talking about, even though we're trying to describe similar practices. Our cities have living walls, and that kind of energy is something that's very difficult to capture with declarations of what street art should be.

As academics, we tend to work on top-down theories and categories that we produce to explain either how things are, or how we think they should ideally be arranged. Ethnomethodology tries to focus instead on how ordinary people, in the empirical data we can actually see, come up with their own explanatory categories – how we make sense of the world ourselves, so that there's not this gap between how ordinary people make sense of stuff, and use categories like ‘street art’ and ‘graffiti’, and how we as academics use them. Because for me, that is a problem. Collapsing graffiti into the category of street art because it makes logical sense – as you have done in your book Andrea – is problematic for me, because it does not seem to match the ways in which graffiti writers and street artists – not to mention ordinary people – use these categories.

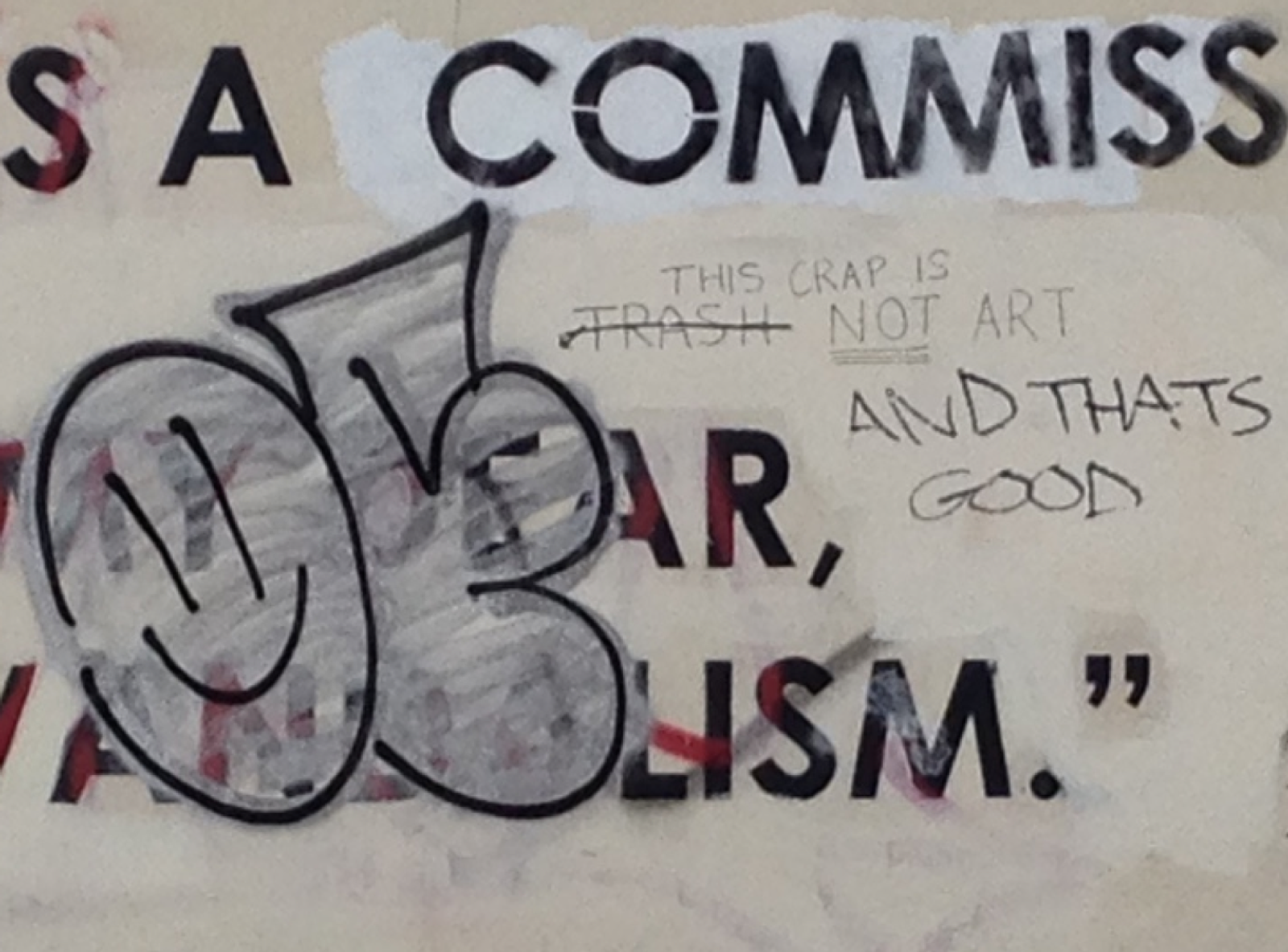

Here is an example of what I mean in practice. Someone has identified the ‘graffiti’ covering Mobstr's ‘street art’ (above) as ‘TRASH NOT ART.’ This is an evaluation. It's also possibly intended as an insult. But what happens next is that someone else intervenes to turn this into a positive evaluation: ‘THIS CRAP IS NOT ART AND THAT's GOOD.’

As we can see from this example, what we think we can do in terms of describing how to evaluate street art and graffiti, or what the qualities of these may be in formal terms, as academics, is actually, in practice, variable, complex and flexible. So even something offered as an insult (or a negative evaluation) of graffiti can be turned into a positive evaluation because maybe, graffiti doesn't always want to be called ‘art’. At least, for this particular writer, in this particular case.

Sabina Andron: So, what is Andrea's book about? What are the themes that are approached in this book and how do we situate these with reference to different bodies of knowledge?

This book is about art and politics and the law. These are big themes, but I believe that everything is about politics. It is also about subversion and vandalism. I would also point to the title of the book, which is A Philosophy Guide to Street Art and the Law – and I'm particularly interested in the fact that you’ve decided to call it a guide, because I think in many ways, that's what it is: it is a very good source for legal precedents, if you're interested in finding out examples of when street artists have had to deal with the law, there are, especially in the footnotes, quite a few good examples of these in the book.

It's also about freedom of speech, which I think is also interesting – especially if you come from a legal background – it's about commodification; it's about resistance, and the issue of moral rights. Taking a step back though, as I am not a legal expert, it may be interesting to consider the wider implications of this for us as citizens of urban environments, whether we produce graffiti or not.

As Susan said, we come from different disciplines, and each of us has a different angle on the various themes that come out of Andrea's book. And I think this is one of the important points that I would like to start with. This idea of studying art and law is something that is a more recent turn. It is an interdisciplinary way of doing things, but I think it's quite crucial that this book was published in a series that looks at the intersections between art and law. Often this is more object-centred, as Susan says, especially if we look at fine art. This is also true of heritage studies' attempts to protect works of art, for example. But I think in this case, in what Andrea discusses, it has more to do with the process and other aspects that are not necessarily object-centred, in terms of the relationship between art and law.

Now, I come from a built environment perspective. While there is a lot of talk about the legal turn in different disciplines, there is also a lot of talk about the spatial turn. Law and space, and how these come together, is something that interests me in my own research, and I think this is another aspect that comes about in your book in certain points. I think that perhaps there is some scope for these kinds of inscriptions, whether they're graffiti or street art, beautiful or not, to rewrite the idea of property. To rewrite what's public and what's private. My own proposal is to rewrite it as a commons, to think about the surfaces of the city as a third-type of property – something that is public by virtue of how it is used, not by virtue of ownership.

Again, I'm not a legal scholar, but the point about this is not for it to be achievable in practice and then the government issues a policy tomorrow. Rather, the point is to give ourselves agency to speculate on how this could be better. Maybe there is a way to approach the law based on looking at rights, and who should have the rights to what – the right to citizenship, the right to produce space, the right to occupy space. So how can we enable a kind of law that protects the right of surfaces to be inscribed, not for them not to be inscribed. Rather than heritage approaches, which stop people from writing on walls, what if there was a form of listing that actually said well, there should be more people who have the right to write something here. So, a kind of law that protects against stillness. Leake Street (a legal graffiti tunnel in London) would be an example of this.

There is no apolitical art. I think there should be, rather, no apolitical art. I think this is the conversation that we should be having. This is the thing that matters: how to produce more politics. Andrea, you started by saying that everything was complex. This is true, but we're not acknowledging it as such, and I believe it is our duty as academics to complicate things, to complexify things, to problematise things. We're here to make things more complicated, not to give TED talks. Philosophy can perhaps be a way to achieve that.

You said one thing that I really liked in your presentation, Andrea, which was that philosophy is about how things should be, and maybe this is a power that philosophy has for us. Of course, we need to clarify what is there first, but then we need to be able to lift it from where it is, complexify it, and then make the world better through speculating, through being imaginative in our solutions.

Max Morris: I think there might be a certain assumption in the argument that you’ve built, Andrea. I really like how you began by setting up that question about art versus vandalism, and then saying that the question is wrong. But then when you were talking about the Fauxreel/Vespa case, I started thinking ‘why did you not consider that to be street art, what was it?’ And by the end of the presentation you came out with this clearer position – because it's commodification. But aren't you just setting up another false binary there, between it's either commodified, or it's subversive, and it can only be street art if it's the latter? Actually, I would argue that commodification can be sub-versive, and there's a lot of examples of that, for example Pop Art, Andy Warhol's work. And you can't really separate, I don't think, street art from Pop Art, because they are so closely aligned in many ways. You could even make another historical argument by saying that commodification is subversive towards a much older, almost aristocratic traditional view of art – which says that only real art, the best art, is that which is done not for profit, in an aristocrat's spare time – and commodification is actually subversive towards that much older conservative notion of art.

Andrea: Thank you for your question. I define subversiveness in terms of the rejection of what I call the corporate regime. Street art calls into question the commodification of our public spaces – street artists transgress the rules of market economy by being a ‘gift’ to the city. So, the idea is that by being a gift you have something that is excessive in many ways, it basically makes you question all sorts of assumptions that you have about public space. One of the aspects that people are most puzzled by when they think about street art and graffiti, is that the artists get nothing out of it, and they usually spend their money to do this work, for free. As Michel de Certeau argues, in capitalist economies gifts carry a subversive potential insofar as they challenge the logic of value exchange. Gifts are not traded with the expectation of receiving something in return.

Susan: But do you think graffiti (as opposed to street art) is received as a gift, normatively?

Andrea: I get this question all the time. Not to dismiss the question, but we struggle to understand what is a gift, if not in terms of trading. So, the idea is that today we understand gifts as a way of, if I give something to you, you give something to me.

Susan: But what if I give you something that you don't want? And what if it's not really intended for you, but for a subcultural audience that you are not a part of?

Andrea: The point is that in traditional gift-giving you can receive gifts that you didn't want, and that you didn't expect.

Susan: But then you understand that this was intended as a gift, with benevolent motivations, even if you don't like it. This seems true of the way that street art is often offered and received, but I am not sure that you can include graffiti in this claim. There is still a hierarchy of aesthetic worth at work here, and arguably street art and graffiti are still received very differently by the general community – and in any case, it seems that they are intended for very different audiences.

Andrea: But that's the way that we treat gifts today – traditionally. It seems to me that the central idea of the gift is that you give something without the purpose of economic return. For me, to be subversive, for street art, is not to be commodified.

Luke McDonagh: There's something that struck me about your book. It's a series of decisions that you’ve made, which are quite brilliant, in their way. You know, you decide what subversiveness means in the context of the book, and then everything flows from that. You know, even the title ‘A Philosophy Guide to Street Art and the Law’ is a different thing to ‘A Philosophical Guide to Street Art and the Law’. It's an interesting thing to do, a philosophy guide to street art – much more so than doing just something that has to do with the law. Because as we have seen from these differing perspectives, street art is something that is incredibly fluid. And I think that it is so fluid that as soon as you draw a line, you begin to lose some of that unique character. There's so much going on here, it's impossible to capture, even with these five academic disciplines represented here tonight. You could not have a philosophy guide unless you made some clear points. But when you do that, you begin to lose something else, somehow – some of the messy details.

Andrea: I perfectly agree, and everybody hates philosophers, because they like to define things. For good reasons, philosophers have this attitude where they want to tell you what things are.

Susan: Or what they should be.

Andrea: What I try to provide are conceptual tools that allow us to clarify the problems we face. But sometimes as a philosopher, I see the wrong questions. There are all sorts of assumptions that we bring to the mix, often without actually being aware of those assumptions. That's why we need to take an interdisciplinary approach.

Andrea Baldini is Associate Professor of Art Theory and Aesthetics at the School of Arts of Nanjing University, China.

Enrico Bonadio is Senior Lecturer in Law at City, University of London.

Sabina Andron is Teaching Fellow in Architectural History & Theory, Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London.

Susan Hansen is Chair of the Visual and Arts-based Methods Group in the Department of Psychology at Middlesex University, London.

Baldini, A. (2019) A Philosophy Guide to Street Art and the Law

Leiden: Brill. Available from brill.com