This article examines an esoteric form of memorialisation that is specific to graffiti subcultures. It is one where the friends of a deceased graffiti writer continue to write the dead writer's graffiti name in public space. This form of memorialisation can conceal the fact that the deceased graffiti writer has died to all but initiated graffiti community members, making it appear as if they were still alive and producing new work. This article will explore this form of memorialisation through some ethnographic observations on the death of Philadelphia graffiti writing legend Razz, and will discuss who has privileged access to rightfully produce these memorials. This type of memorial is a complex and compassionate act of remembrance. It functions both as memorial and as a furtherance of the deceased writer's reputation and street fame.

When someone who was cared for dies it is standard practice to remember and memorialise them. In western cultures that way often manifests as a funeral service and a gravestone to commemorate their existence. There are, of course, many other ways a person can be memorialised and many other small rituals of remembrance that those who cared about the departed participate in. Depending on who that person was, their personal beliefs and cultural background, what they did while they were alive, and the groups that they were part of while they were alive, these rituals of remembrance can take many forms. Private, personal memorialisation among those who knew the deceased are most common, but forms of public tribute are also typical. A dedicated bench in a park, or a tree planted with a plaque to show passers who it was planted for, or a donation made in a dead loved one's name so that their name will appear on a public list, are some typical ways that the living publicly remember their dead.

When the deceased is someone who had cultivated a public reputation, the forms of memorialisation expand. Frequently, they are retrospectives of the deceased's career; performance highlight reels, pieces they are best remembered for, or stories shared about how they made their mark on their chosen fields. In the digital age, social media have become a very capable outlet for producing these kinds of memorials. Facebook pages (and similar forms of social media) of the deceased become spaces where stories, memories, and condolences for and to the departed are shared (Brubaker, Hayes, & Dourish, 2013). And platforms like Instagram offer spaces for users from all over the world to display tributes or RIP pieces, and to comment on the impact the individual, or their work, had on them. These spaces become crucial spaces of public memorialisation that anyone can observe (assuming the pages are publicly shared) to know that someone has died, and that that someone was important to, and impactful on others. All of these forms of remembrance do at least two important things; (1) they remember the deceased and (2) they publicly acknowledge that the person being remembered has died and thus will not produce new work.

This article will examine a different type of memorialisation, a more esoteric one that takes place in graffiti communities where the graffiti writing friends of the deceased continue to write the dead graffiti writer's name. This form of memorialisation can conceal the fact that the deceased graffiti writer has died to all but the initiated graffiti community members, while also furthering the dead writer's graffiti presence in the collective memory of the graffiti community and on the physical spaces of their particular graffiti locale (as such it will forego a discussion of digital memorialisation and tribute, leaving that discussion for another time). It is typically only understood by the properly initiated and can mask the dead graffiti writer's death from the general public, making it appear as if they are still alive and producing new work. This article will explain through ethnographic example this form of memorialisation, and it will discuss who has privileged access to rightfully produce these memorials. It will make the case that this type of memorial is a complex and compassionate act of remembrance done to keep the deceased graffiti writing entity alive in the streets, and it is one that inducted graffiti writers spot immediately. As such, it is a form of public memorial in line with the traditional types of public memorialisation (dedicated benches, trees, etc.), but it is also one that functions both as memorial to those in the subculture and as a furtherance of the deceased writer's reputation and street fame to both those inside and outside the subculture. This process will be examined through the death of Philadelphia graffiti writing legend Razz.

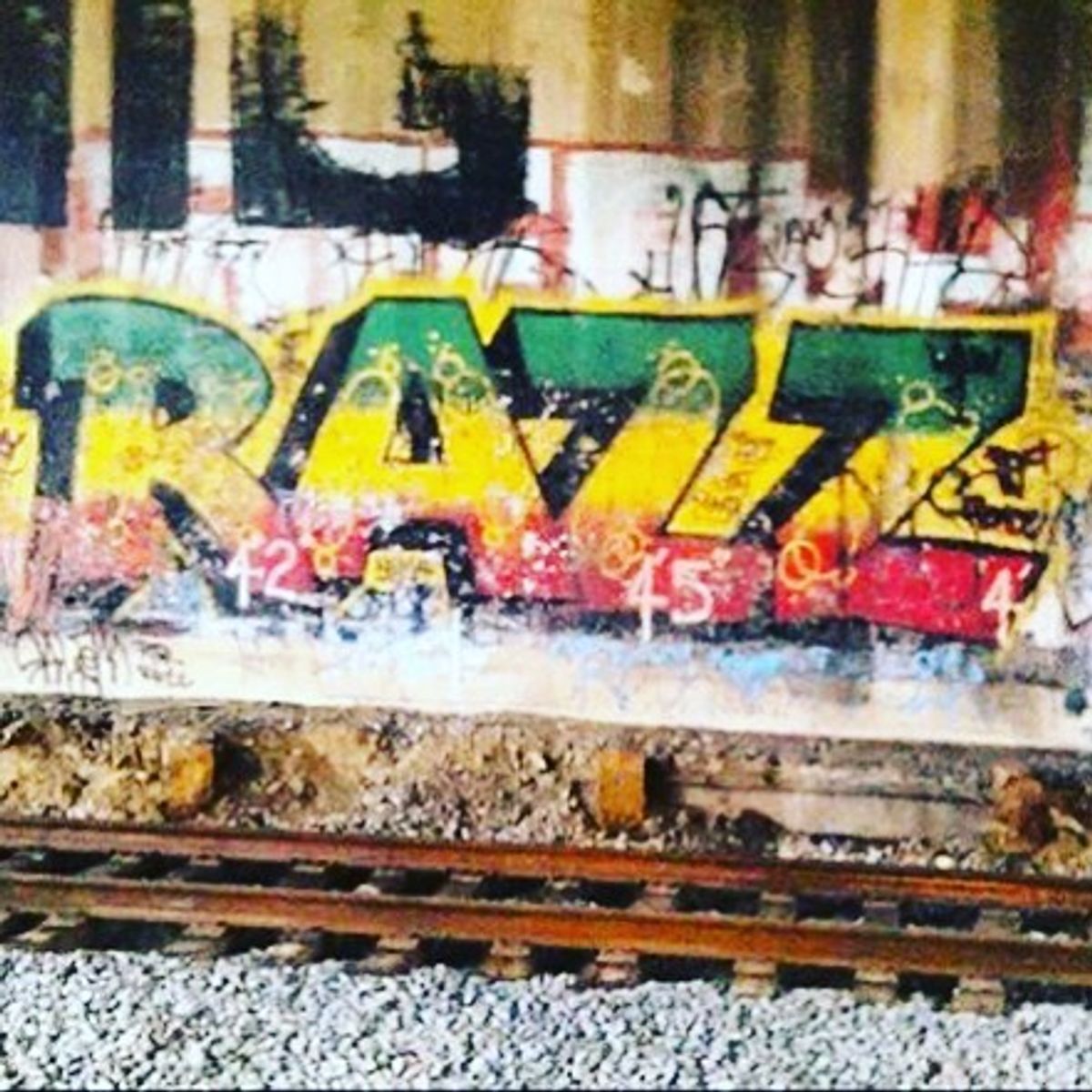

In the history of Philadelphia graffiti there are many shining stars; Cornbread, Mr. Blint, Estro, Disko Duck, Kair, Espo, to name a few. But no list of Philadelphia graffiti luminaries would be complete without including Razz. Razz was a true graffiti presence on the walls of Philadelphia in his time. He was ‘all city’, which means he had his graffiti up in all neighbourhoods of Philadelphia. He founded the LAW1 graffiti crew and was their president for years. In that capacity, he mentored many young graffiti writers and made sure they knew how to write graffiti properly, and knew how to respect the culture and traditions of Philadelphia graffiti. His place in the graffiti subculture as a whole was assured when he had an entire section devoted to him in the classic graffiti culture book The Art of Getting Over (Powers, 1999), which explained graffiti to so many who had seen it but not understood it. He died on May 5, 2012, and so the community lost one of its longest standing and most important members. Of course, he had to be remembered, celebrated, and memorialised. The Philadelphia graffiti community would come together to do just that. And in so doing they would teach a lesson about how the culture remembers its fallen practitioners, and how graffiti writers all over the world understand their identity and social presence.

There is an old saying that says when someone dies they really die three deaths. The first is their physical death, the second is when the people who knew them die or forget about them, and the third is when they are forgotten by all of society because what they have created disappears, or is lost, or forgotten. This is a fitting adage for how graffiti writers understand death in terms of their graffiti identity. It also allows us to more clearly understand the process of memorialisation that graffiti writers undertake.

What follows are my field notes from the night of Razz's memorial held by the graffiti community with only minimal editing for clarity and linearity. Succeeding them are some critical reflections on the events to provide greater understanding of their meaning and importance.

Razz died Saturday (5/5/12). I've heard it was from lung cancer, but haven't read that officially. Baby and Nema painted a tribute piece together after hearing the news. There's an all crew, all city meet up tonight to honour and remember Razz. Baby is taking me. I'm not sure what to expect but I'm guessing something in between a wake, a New Orleans second line funeral, and the opening scene in Warriors (1979).

The meet-up is at a restaurant in West Philadelphia near the University of Pennsylvania campus. Baby, Lady, Nema, and I arrive together and Nema and I go to the bar and grab a drink. Baby and Lady go over to where everyone is meeting. The memorial group is largely African American men who are in their late 30s to early 40s. I get the feeling that this bar is not used to having this many black men in it, especially when some of them fit the media-established ‘thug’ aesthetic. They are passing around blackbooks, standing in the lanes between tables talking and being in the waitresses’ way. A few times what I'm guessing is the owner comes out and eyeballs the crowd with clear disdain.

The crowd is largely members of the graffiti crew Razz founded, LAW1. I meet Bum, Bard, Demo, Expo, Caze, and a bunch of other people. Once everyone has settled in, blackbooks get passed around and people section off into little groups and watch each other write in the books and pass them around to get more names in them. After just about every tag I see people do they write ‘RIP Razz’ next to it. Some just write their tag and then Razz next to it in Razz's famously straightforward style, making sure to connect the R and the A.

The night is dwindling down, people are shuffling out slowly and a lot of people are still out front smoking and talking. Outside it has started raining and those who are out there are standing under an awning close to the door for cover. All of a sudden everyone comes back inside hurried in by the ‘owner’ and five cops. The ‘owner’ and the cops walks over to the area where everyone is sitting and the owner says ‘you all smell like weed, get out’, the cops say, ‘alright, that's the end of your night’ and hustle everyone outside. Nema and I slide to the bar and escape from the fray without being noticed, Baby and Lady are away from it all anyway and a few old heads are not hassled. But anyone who looked ‘urban black’ got thrown out. Baby, Lady, Nema and I sit at the bar until this all calms down. We settle our tabs and go outside, fuck this place now.

We all congregate in the front alcove to get out of the rain, and Expo goes back inside to investigate why the cops got called and everyone got thrown out. He finds out it is as the ‘owner’ said, because people were smoking weed out front and it was wafting in through the door and bothering patrons. This is a legitimate complaint, but it also feels like a convenient excuse for getting rid of patrons that were deemed unsavory.

The biggest issue is that when the cops threw everyone out they confiscated all the blackbooks. Everyone is really upset about this. These were not just ordinary blackbooks, which would be a big enough shame to lose, these were ones that are full of memorials to and memories about Razz. Everyone seems to agree that even if someone went down to the police station the next day there is little chance of getting them back.

The rain has slowed to a drizzle and those who are still hanging around are talking about going painting. It feels like the right next step in the celebration/memorialisation of Razz, but people also want to go as a kind of ‘fuck you’ to the police who hassled everyone and seized the black-books. Caze says he knows a spot we can go paint, but he has to go home first. He says he'll text us in a bit. In the meantime Baby, Nema, Lady, and I get in my car and just kind of start driving around. It feels risky to keep standing around in front of where everyone just got thrown out of. So we leave without a destination in mind.

We drive around for a bit and end up in the north Broad St. area. It's late enough and dark enough that Baby and Nema want to do some hop outs. When the coast is clear I pull over and they hop out and catch tags on the side of a building. After their tags they write ‘RIP Razz’, but then Baby walks a few feet and puts up a Razz tag in his style. Nema sees this and does the same. They get back in the car and I ask them why they put up Razz tags and Nema says ‘gotta keep his name alive in the streets.’ (field notes)

As that night continued, we ended up painting some throw-ups under a bridge since the rain picked back up. But the events of that night up to this point are very telling when it comes to understanding how graffiti writers think about their presence in (and on) the city and how that presence affects their subjective identity. They also exemplify how graffiti writers think about their relationships to each other, and how they conceive of their legacy of graffiti writing. The most important thing that happened was both Baby and Nema engaging in a form of memorialisation where they put up Razz's tag as true to his original style as they could.

Before we can move on it has to be noted that this research took place in Philadelphia, and that Philadelphia is where graffiti as an urban aesthetic practice based around forms of competitive recognition began (Mitman, 2018). This does not mean that this particular form of memorialising deceased graffiti writers is exclusive to Philadelphia; quite the opposite in fact, as will be shown at the end of this article, this practice takes place in many geographically disparate communities. But since Philadelphia has a long history of graffiti on its spaces and an intricate, culturally understood system of guidelines that tell graffiti writers what spaces are and are not acceptable for graffiti, it is important to acknowledge the location and the associated cultural history. Further, it is important to understand that the guidelines of graffiti practice that will be discussed are just that, guidelines. These guidelines are internally imposed by the graffiti culture, but it is up to the individual graffiti writer to choose how closely (if at all) they adhere to them. Because one of the ways the graffiti community thinks of itself is as anti-authoritarian rebels (Macdonald, 2001), the degree to which these guidelines are adhered to will vary. Some writers will adhere to them strictly, while others will choose to only abide by the ones that are convenient for them in the moment, others may ignore them entirely. The one aspect of the rules that has some universality, though, is that when a writer feels another writer has violated their public graffiti presence, or that a writer has violated the community standards, it is this collection of guidelines that get referenced as supporting evidence for the claim (Mitman, 2018).

The guidelines lay out forms of acceptable cultural practice (see Powers, 1999: 154–155, or for a more comprehensive discussion, see chapter 3 of Mitman, 2018). One of the important things they describe is how and when existing graffiti can be painted over so new graffiti can be created. In their most rudimentary form, these guidelines apply a visual hierarchy to graffiti saying that a piece is better than a throw-up, and that a throw-up is better than a tag. As such, when it comes to reusing space that already has graffiti on it, a piece can be put over a throw-up, and a throw-up can be put over a tag. This simple guideline is one that is naturally understood in all graffiti communities, but in Philadelphia this particular rule is complicated by the fact that the Philadelphia graffiti community holds the tag in very high regard. A well-executed tag (particularly a Philadelphia-specific style like a wicked, a tall hand, or a gangster hand) can be as well respected as a throw-up, and as such putting any graffiti other than a piece over it can be considered an act of disrespect.

This matters for this discussion for two reasons. One is that good tags, and tags of well-known graffiti writers tend to remain untouched much longer on city walls in Philadelphia, unless the city or the owner of the space buffs the space clean, which they tend to do indiscriminately. The second reason is that it is absolutely forbidden in the graffiti community to ever paint over a dead writer's work. They are not alive to produce more and, obviously, they are not able to retaliate or reclaim their name, so painting over a dead writer is considered one of the most reprehensible and disgraceful things a graffiti writer can do. Painting over their tags serves as an act of erasure that diminishes the deceased writer's public presence and acts as one more step toward erasing them from history and public memory altogether. It can cause the dead writer's friends to seek retribution against the graffiti writer who went over their dead friend. It can also damage the offending writer's future chances of recognition and participation in that graffiti community. A graffiti writer who paints over a dead writer's work, even accidentally, can suffer great reputation damage within the community which can cause other writers to target their work, be unwilling to paint with them, or just generally be unwilling to associate with them in any way. This can be detrimental to a graffiti career because, while the quality and quantity of work a writer puts up is critical to their graffiti reputation (Schacter, 2008), equally important is their involvement in, and recognition from the rest of the graffiti community (Halsey and Young, 2006). Simply put, painting over a dead writer's work is considered so objectionable that it puts an offending writer in bad standing with the overwhelming majority of their graffiti community.

So, what Baby and Nema did (and what many other writers did in the days after Razz's death as well), was a simple act that had embedded in it a great deal of compassion and complexity. Putting Razz's tag up helped to ensure his presence on the streets and in the collective memory of the graffiti community and city. It is often said that graffiti writers primarily write graffiti for fame (Castleman, 1984; Lachmann, 1988; Ferrell, 1996; Powers, 1999; Snyder, 2009), and to achieve fame they must go out and endure the risks associated with illegal graffiti writing. These risks, among others, come in the form of risks to their freedom from being arrested, and risks to their personal safety from potential assaults from the police or fellow writers, or from getting injured while entering abandoned and/or dangerous places. Additionally, writers endure risks to their personal financial well-being because if they are caught and arrested the punishment they receive from the court is most often a hefty fine. What this means then is that to accept the risks of writing graffiti and to eschew writing one's own graffiti name (thus diminishing the collective amount of fame they can achieve from their graffiti writing efforts) in favor of writing their dead friend's name, is a compassionate act of memorial.

This form of memorialisation, where the friends of a dead writer go out writing graffiti and also put up their dead friend's tag in as close to that dead writer's style as they can, is complex as well. It serves as a noteworthy form of remembrance in two ways.

One, the act of going out and writing with other writers in the service of putting up a dead writer, functions as a kind of ritual of remembrance. It can serve as a type of psychotherapeutic act (Reeves, 2011) that allows writers to process the loss of their dead friend, while also acting as a type of catharsis that allows them to let go of some of their negative feelings about the loss. I have written previously about how graffiti writers use the act of writing graffiti as a cathartic form of art therapy that allows them to process and deal with personal issues (Mitman, 2018). In this instance, writing a dead friend's tag functions as a kind of praxis (Arendt, 1998) where the graffiti writer is cognitively, physically, and emotionally engaged with their particular way of grieving that is associated with the act of memorialisation of putting up their dead friend's graffiti name. This practice offers the grieving graffiti writers a type of catharsis, while also creating a community of remembrance through all those graffiti writers who went out and put up Razz tags in the time after his death.

Going out and writing a deceased friend's tag, and seeing that others have done the same, reinforces the sense of belonging and friendship within the graffiti community. Halsey and Young (2006) describe how important it is for graffiti writers to feel like they are an integrated part of a larger community through friendships with vetted members, as do Castleman (1984) and Monto, Machalek, and Anderson (2012). Going out writing graffiti with friends to remember and memorialise a dead friend attends to this crucial part of cultural participation, but it also strengthens these feelings of friendship and community integration that are so important and motivational to so many graffiti writers.

These feelings are strengthened in another way as well. When writers see their dead friend's tag up, and know the tag was done after their friend's death but do not know who did it, this expands their feelings of connection and involvement and creates a kind of semi-anonymous community of remembrance. This increased feeling of interconnectedness occurs because when writers see their dead friend's tags appear on the walls after they have died, it indicates that other writers cared about their friend in a similar way and are equally willing to engage in personal risk-taking to continue to propagate that individual's graffiti presence in the city.

A dead writer becoming more present on the city walls after their death serves as evidence of the impact that their existence had on the graffiti community. Whether it is many writers putting them up, a few, or even just one dedicated writer, the fact that those in the graffiti community can know a writer has died and see that writer's representedness increase, shows that they were an embedded and important enough part of that graffiti scene for someone to continue their legacy. This act then bonds those who do it to each other through a shared friendship with the deceased writer, and more firmly enmeshes both the dead writer and those reproducing their tags into that graffiti community.

This point comes with a caveat though. For this act to be respected as a legitimate type of memorial by the graffiti community, it must be at least tacitly understood that those writers putting up their dead graffiti friend were indeed friends with the departed. As previously stated, friendships are of critical importance to graffiti writers and these typically include things such as being prepared to be on the lookout while a fellow writer is painting, or helping to resolve any ‘beef’ that may arise. This could be by acting as an intermediary or negotiator between parties, or as someone willing to fight by your side to resolve it, or they could act in myriad other supportive roles.

In graffiti communities, friendships can also serve as a type of subcultural capital (Thornton, 1996). Being friends with a well-known and respected writer can confer increased subcultural status onto their friends. As such, it matters that there was a legitimate interpersonal connection between the graffiti writers, because when doing this, graffiti writers will most often write their name and their dead friend's name thus associating the two together. If the graffiti community does not believe the writer putting up the dead writer's name was a friend of theirs, the act is then considered an act of appropriation. It can be seen as a disrespectful and offensive act done to achieve a quick type of illegitimate street fame by associating one's graffiti reputation with a well-known and now deceased graffiti writer. It is thought of as a type of attempt at reflected notoriety dishonestly cast from the dead writer's name onto theirs; a kind of theft of subcultural capital.

Two, putting up a dead writer more indelibly (literally) marks them on the city. This is very important. Having a visual presence on the streets (or as graffiti writers say ‘being up’) is the primary way that graffiti writers compete with each other and cultivate reputation. It is also the way writers stay relevant members of their graffiti scenes. As such, the longer a writer is active in their graffiti scene and the longer their graffiti work lasts on the walls, the more their reputation and importance to that graffiti community will grow. One of the best strategies for writers to acquire fame is to stay active for a long time. The two biggest hindrances to maintaining active participation are incarceration and death. A graffiti writer stopping for any other reason is considered to have quit or retired. The community believes that if they were truly dedicated, they would overcome whatever barriers they face to get back out there and continue the practice of graffiti writing. As such, putting up a dead graffiti writer's tag serves to maintain their presence both visually and ideologically to that graffiti community. This can be clearly seen in Baby and Nema putting Razz's tag up on the wall, and by how Nema exhibits his understanding of this process when he says ‘gotta keep his name alive in the streets’. Putting up Razz's tag furthers his presence on this city, continues his participation in the graffiti scene, links him visually and conceptually to those graffiti writers currently producing graffiti (as opposed to those who have for whatever reason stopped), and functions as a memorial for those who are integrated enough to understand it as such. This is important because maintaining public presence can be very difficult for writers. They see themselves in a constant battle against ‘the buff’.

‘The buff’ comes in many forms, but it generally means for a writer to have their graffiti obliterated from public view by some authoritative structure. It is such a concern in graffiti communities that the process gets embodied as an entity simply called ‘the buff’, that writers envision themselves in a constant war against. When the city decides to buff a space, they literally can erase generations of graffiti history from the walls. Entire careers can be annihilated when a city undertakes a dedicated graffiti cleanup effort. And those who cannot reassert their presence can be eradicated from the collective memory of their graffiti community. Successful graffiti writers are those who continue to put up new work to compensate for what is lost, and who increase their fame by improving their skill, presence, and reputation in the process.

Writers paint over each other's work as well. They erase each other (though this is not considered part of ‘the buff’). It is a begrudgingly endured and fairly common practice, but painting over a dead writer is absolutely unacceptable, as it is considered an act of disrespect. Writers work to be aware of each other's status in the community, of who it is they consider going over, and thus of who they are potentially going to offend. What this means is that the collective graffiti subculture expects its members to be armchair historians of their local graffiti scene, and to be aware of who other practitioners are and if one of them has died. Generally, this sort of information travels quickly through the community by word of mouth (or knowledge shared via social media). As such, claiming ignorance of a writer's death (especially as an excuse for painting over their work) is not tolerated. Claiming to be a member of the graffiti community, but also claiming to be ignorant of the loss of one of its members are irreconcilable claims.

When graffiti writers put up their dead friend in the same style that friend used it, it is very difficult for the uninitiated to tell what is a memorial and what was actually produced by the dead writer. The average urban resident will see a memorial of this type and merely think the dead writer is alive continuing their graffiti career. This is very much the point of this act. It perpetuates the idea to the public that the dead graffiti writer as an entity in the graffiti community still exists and is still producing work, and it increases the deceased writer's fame.

But an additional part of the point of this act is the message it sends to the aware members of the graffiti community. It serves as a memorial or tribute that shows that other writers care about the friend they lost. Additionally, it being a memorial goes a long way to ensure that it will not be adulterated or gone over by other members of the graffiti community. This is because, while painting over a dead writer's work is verboten in the graffiti world, painting over a tribute to a dead writer is almost as offensive and, thus, is guaranteed to bring the offending writer a serious amount of beef. The dead writer then has a continued and increased presence in the city from their friends. They become a dead, but active member of the community, their mantle carried on by their friends. In this way, a dead graffiti writer can continue their career for as long as their friends are willing to put them up. The initiated will see this as a sustained act of friendship and remembrance, while others will just see a graffiti writer's street fame increasing.

The fact that the dead graffiti writer's tags are done in as close to their original style as can be reproduced, is important. Partly it is an act of respect done for the dead writer that reinforces and acknowledges their stylistic contributions to the graffiti scene. But it also means that these new tags intermingle with the existing ones the dead writer left behind in a way that (hopefully) makes the original ones and the memorial ones hard to distinguish from each other. In this way the dead writer lives on, but their graffiti identity is now co-constructed by their friends who put them up, and through the rest of the graffiti community being aware that the tags they see are simultaneously further steps toward fame for the deceased writer and forms of memorial to them. The difference between the original tags and the new, memorial ones is easy for the initiated to see. The original ones have what Benjamin (2008) calls an ‘aura’. They possess a quality that could only have been produced by the original graffiti writer that is clear in the tag to those who are aware of, and embedded in, their graffiti community.

The co-construction of their graffiti identity gets preserved and extended, but also reflects back on the work they produced before they died. These new tags done as memorial influence the originally produced graffiti in a way that makes those who see it (and can identify its aura) recognise that the graffiti is an original production of a now dead graffiti writer who is actively being memorialised, thus affecting the interpretation of that graffiti. The interpretive shift is that, instead of being just graffiti from a writer, it now gets at least partially seen as a monument from a now dead graffiti writer to themselves. This consciously or tacitly imposes on the observer the subjective distinction between the graffiti writer as a person who is now dead, and the graffiti writer as representation-based entity that still exists. It, and how it interacts with the new memorial tags, produce a narrative that speaks to how important and integrated that graffiti writer was to their graffiti community.

The life after death that this type of memorial grants certain dead writers means that their involvement in, and influence on, the graffiti community continues until their friends stop putting them up. This is incredibly important in and of itself. It means that well positioned and respected graffiti writers can continue to have influential graffiti careers long after their death. But this process affects practicing community members as well. It allows them to witness the lasting impact an influential and revered graffiti writer can have after their death. This can make them work harder to create a respected reputation stylistically and to cultivate a respected reputation within the community, with part of their motivation for doing so being the unspoken hope that someone carries their graffiti self and public presence on after they die.

Beyond this it also serves to reinforce the graffiti community code of conduct and guidelines. Graffiti writers are socialised into their graffiti community and taught its rules through a Vygotskyian (1978) process. There is a type of psychosocial symbiosis that occurs where younger or more novice practioners learn from their interactions with older or more established graffiti writers what the rules of the practice are, how to properly engage in it, what its history is and why that is important, how graffiti writers understand space and property, how people who violate the rules get sanctioned, etc. Through this process graffiti writers cultivate their graffiti identity, but in so doing they must necessarily do it in relation to the existing graffiti identities and personalities that they have interacted with and know of. For emerging graffiti writers what it means to be a writer is framed through what they understand graffiti writers to currently be (Castleman, 1984; Lachmann, 1988; Ferrell, 1996; Macdonald, 2001; Snyder, 2009; Mitman, 2018).

Positioning theory (Harre and Lagenhove, 1999) tells us that we understand and create our being and selves through a subjective social and personal process, with meaning being made through language and sign systems, forms of symbolic and semiotic interaction, and learned models. But the way we create, understand, and interpret these social, semiotic, and learned systems is based upon who we have learned them from, how we have internalised them, and how the cultures and societies we have learned them through have influenced all parties involved. Simply put, this means that understanding and creating our subjective identities is largely a social process deeply influenced by those that we interact with, and by how we understand those who are valuable to the cultures that we seek to belong to. What this means for this discussion is that through the process of being indoctrinated into being a graffiti writer, writers develop a personal understanding of culturally held values that are passed on from one generation of graffiti writers to the next. Amongst the many subculturally specific things they learn, they learn that this type of memorial is a highly respected way of recognising dead graffiti writing friends, a way of engaging in a type of cathartic processing about the loss of that friend, and a tactic for displaying that friendship to the community that also perpetuates the deceased graffiti writer's graffiti identity.

Engaging with this process affirms one's own identity as a graffiti writer. It also acknowledges the importance of the dead writer, the importance of the community of friends within the graffiti community, the importance of that dead writer's contributions to the culture, and the importance of the history and rules of the collective graffiti culture. These dead writers whose friends keep their name alive are writers who continue to exist as members in good standing with the community. The existing community seeing their name get extended beyond their death and knowing how they behaved while they were alive fortifies those community guidelines that allow the competitive aesthetic practice of graffiti to continue from generation to generation, with the new generation having respect for the rules and contributions of the previous ones.

Razz's death has been the primary way that this practice of memorialisation has been examined. But I have also said that Razz was a foundationally important member of the Philadelphia graffiti community. As such it could be assumed that this type of memorial is reserved for only the most well-known and influential members of a graffiti community, or that it is a practice localised to Philadelphia's graffiti community. Neither of these ideas are true. Any graffiti writer from any graffiti community who was a respected and well-liked member of their graffiti community can have this type of memorial bestowed upon them by their friends. Certainly, there are dead writers being remembered in this way in graffiti communities all over the world right now. But allow me to offer a few examples to illustrate how this practice extends well beyond Razz and Philadelphia. San Francisco bay area graffiti writer Tie has been living on in the graffiti world thanks to this practice long after his appalling murder in 1998. Louisville, Kentucky graffiti writer 2Buck has lived on in this fashion after his untimely death in 2015. As have Oil, a graffiti writer who made his name in the Los Angeles and Miami areas, who died in 2013, and Houston born Nekst, who made his name all over the United States and Europe, who died that same year. These examples illustrate how far beyond the confines of the Philadelphia graffiti scene this practice extends. There are countless other graffiti writers being memorialised in this way, and the list keeps growing. But for those dead graffiti writers who were respected and who have dedicated graffiti writing friends, their graffiti identity can live on and on. In this sense, it is true that dead graffiti writers never die, they just fade away.

Dr. Tyson Mitman studies public aesthetics, graffiti culture, and identity. He is specifically interested in how individuals who produce public art construct their identities within their subculture, how their interactions with public space produce a type of political discourse, how their subcultural practices affect spaces and those who use those spaces, and how all of this interacts with forms of subjective consumer identity. He also studies how graffiti's presence affects the way spaces are ideologically constructed, and how producing graffiti helps co-create the individual from subjective and cultural perspectives. He examines how participation in the subculture affects subjective identity construction, and how the efforts to attain specific forms of subcultural capital interact with cultural structuration and individual practice. His other research interests include subjectivity, subculture studies, visual culture, deviance, the politics of resistance, issues of public space and inequality, theories of democracy, access to political voice and agency, beer culture, and morality. He is the Course Lead for Criminology at York St John University, where he lectures in sociology and criminology.

- 1

These field notes come from the ethnographic fieldwork that would lead to The Art of Defiance: Graffiti, Politics, and the Reimagined City in Philadelphia (2018). For this project, I became an integrated member of the Philadelphia graffiti community and a graffiti writer myself.

- 2

Drawing sketchbooks typically bound in black are used by graffiti writers as practice spaces, spaces to plan out the work they want to paint on walls, as autograph books to document friendships between writers, and as evidence of interactions with more famous writers.

- 3

Often just called ‘throws’, they ‘are letter outlines of one color, filled in with a different color, often the whole thing is then outlined again, or ‘shelled’, with the fill-in color or a third color’ (Mitman, 2018).

- 4

Complex, intricately designed and often brightly coloured works of graffiti (Mitman, 2018).

- 5

A graffiti writer's stylised signature.

- 6

These are all styles of tagging that have aesthetically regimented letter structures and connections between letters. They are also heavily influenced by their historical cultural development, and thought of as possessions of the Philadelphia graffiti community to be protected and respected. For examples of these styles and a full description, see Mitman (2018).

Arendt, H. (1998) The Human Condition: Second Edition. University of Chicago Press.

Benjamin, W. (2008) The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. Penguin UK.

Brubaker J., Hayes G. & Dourish P. (2013) Beyond the Grave: Facebook as a Site for the Expansion of Death and Mourning. The Information Society, 29(3): 152–163

Castleman, C. (1984) Getting Up: Subway Graffiti in New York. MIT Press.

Ferrell, J. (1996) Crimes of style: urban graffiti and the politics of criminality. Northeastern University Press.

Halsey, M. & Young, A. (2006) Our desires are ungovernable: Writing graffiti in urban space. Theoretical Criminology, 10: 32.

Harre, R. & Lagenhove, L. (1999) Positioning theory: moral contexts of intentional action. Blackwell.

Lachmann, R. (1988) Graffti as Career and Ideology. American Journal of Sociology, 94: 22.

Macdonald, N. (2001) The graffiti subculture: youth, masculinity, and identity in London and New York. Palgrave.

Mitman, T. (2018) The Art of Defiance: Graffiti, Politics and the Reimagined City in Philadelphia. Intellect.

Martin, A. Monto, J. M., Terri L. A. (2012) Boys Doing Art: The Construction of Outlaw Masculinity in a Portland, Oregon, Graffiti Crew. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 42: 259–290.

Powers, S. (1999) The Art of Getting Over: graffiti at the millennium. St. Martin's Press.

Reeves, N. C. (2011) Death Acceptance Through Ritual. Death Studies, 35: 408–419.

Schacter, R. (2008) An Ethnography of Iconoclash. Journal of Material Culture, 13: 35–61.

Snyder, G. J. (2009) Graffiti lives: beyond the tag in New York's urban underground. New York University Press.

The Warriors (1979) Directed by Hill, W. USA.

Thornton, S. (1996) Club Cultures: Music, Media, and Subcultural Capital. Wesleyan University Press.

Vygotsky, L.S. & Cole, M. (1978) Mind in Society. Harvard University Press.