One of the things that's really interesting about this project is your visual-sonic collaboration. How did this come to be as a collaborative project?

Ian Strange: I've been a massive fan of Trevor's work for a long time. His music was soundtracking my studio for years. A while ago I went to follow him on Instagram and saw that he was also following me, so I immediately messaged. I was excited to know that Trevor was aware of my work and reached out to say I'd love to find a way to collaborate at some point in the future. This was a while ago, but it's always been a bucket list goal to work with him in some capacity on a project, but I didn't want to come back to him with anything that wasn't significant.

And then, flash forward to 2020. I found myself in Australia in March and then lockdown happened, and I couldn't go back to the US. So I went back to my hometown of Perth. While I was there, I returned to a house on Dalison Avenue that I had always been fascinated by. I found out more about the house and discovered it was getting demolished. So, I reached out to Trevor again to say I may have a project for us. This was early in the pandemic, in the midst of lockdown.

Trevor Powers: When I got that initial message on Instagram I got so excited because I'm such a big fan of Ian's work. But there wasn't a specific idea yet. It was that whole thing of, ‘hey we should work together on something’, but we didn't know what it was going to be. And so, I just kept thinking, well, hopefully that works out. And then I think it was maybe two years after that when Ian sent me a message with the idea of Dalison. I really don't do much collaboration with people outside of my circle. And when I do, it's always music, so there are certain engineers I work with on a regular basis. I'm not one to generally collaborate with other musicians, let alone across other fields of art. It's not because I'm against it. It's because music tends to be such a personal thing for me. It might sound stupid, but it really does feel like there's a spiritual aspect to it. But when Ian reached out to me with the initial idea, it checked all the boxes because not only have I always been so excited about Ian's work, but with this project in particular – and the ideas that he gave out of the gate – I felt like I could already see it in my mind. And that's what guides me. That's what spoke to me.

Ian Strange: The thing that I've always loved about Trevor's work is that it has this foreign but familiar, alien but warm texture that is – I don't want to say melancholy, because that sounds too theatrical – but it has a kind of nostalgic warmth and humanity to it, but it's not overt. It has these big wafts of optimism.

You go on these big sonic journeys with Trevor's music, and there's those moments which I love in music where you can feel the composition almost falling to pieces, like someone's pushing it to almost break. And then it falls back in and then it has a warmth and humanity to it, and then it almost falls apart again. There's a reason I listened to it so much. I love his music, and I've absorbed it probably without even knowing. But I hope I wasn't prescriptive in how Dalison should sound.

Trevor Powers: Not at all, and that's what was great for me. I'm not good at working within boundaries because so much of what I do is based on accident. Anytime I have an intention when I sit down to create, the intention is never as exciting as the accident – I'll have this lane I'm trying to drive in, but then I'll stumble on something else. I think it's because being human is such a beautiful thing. But then it's also so fucking hard. I like embracing accidents in music because it captures more of the essence of what it is to be a human.

When Ian reached out, there were a couple of words he said, I think melancholy was one of them. But other than other than a handful of words, I felt like I had a blank canvas to work with. And that was great for me because otherwise it would have been too restrictive. It would have been so much harder because I never really know what I'm going to stumble into. I have an intention, but if there's a blueprint, I usually end up throwing out the blueprint. Because most of the time it sucks.

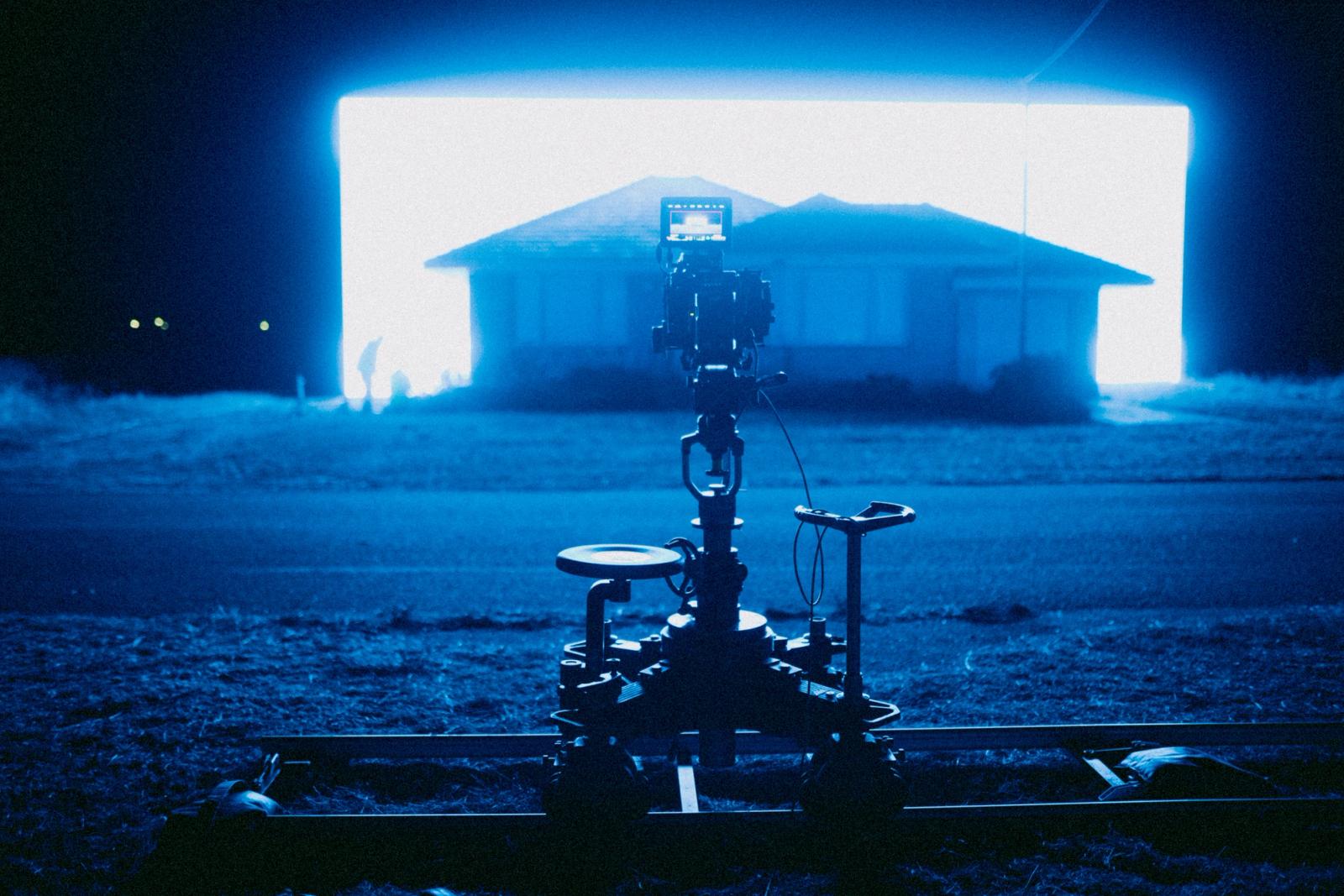

Ian Strange: What I knew I wanted to do with the work was to use a light panel to create three phases where you could light just the house and isolate it floating in space. Then lift the panel behind it so you could cut its silhouette out of the landscape. And then, finally, light the entire landscape around it so you could place the home back in its context. I knew I wanted to move between those moments, where you could have it float in nothingness to then being etched out of the landscape and then pulled back into the context of the landscape and site.

That for me is why it lent itself to being a durational work and a musical collaboration. Most of my previous works are still images or videos, but nothing moved, the lighting wouldn’t change. Whereas Dalison was about trying to shift perspectives over a period of time. A key thematic in the work is time and that temporality – the history and landscape of that house over time, the temporal nature of the home and the ideas it represents, and the context of it literally disappearing with its demolition.

Trevor Powers: Having that combination between familiar and alien was important. That's where it was with the idea of the house. Because houses tend to have a certain atmosphere, a certain spirit behind them, but you don't really know what's inside the house. That's what's alien.

Trevor, were you able to visit the site?

Trevor Powers: No, I never saw it, but Ian was so great about sending me photos and videos and information. So, I felt like I had seen it.

Ian Strange: Yeah, I spammed him with a lot of stuff. There's something poetic about the isolation of that house. And it being created in a moment where everyone was isolated in some way. I know this may be a reverse justification, but I do think there is an aspect of broadcast to this which I really like. The idea that both light and sound can touch things without physically affecting them. The idea that by broadcasting out light, this house touches this entire empty suburb, as does this sound broadcasting out across this empty suburb. With Trevor creating work from a place of isolation on the other side of the world that would then broadcast out across this empty suburb. There's something quite nice about it in this moment where people weren’t able to travel or leave their homes. Trevor called it an anti-concert, which in my head was absolutely perfect. It's like the opposite of a concert. The work is about the lack of community, the lack of site, people not being there – in many ways the work is about that absence.

Trevor Powers: It really is the opposite of the concert in every way possible. Like Ian said, it's a lack of everything rather than everything being present. Whenever I play concerts, I have this feeling that I don't know how to describe. I don't feel comfortable. For me, the process of music is always the writing, the recording. It's this insular thing that comes from the soul. Concerts can be fun, but I definitely have to become a different version of myself to do it. But when Ian had described the house and his plan for the lights it felt like a concert that I was comfortable creating, and obviously the process was all behind the scenes, behind the curtain. The anti-concert aspect of it was something I couldn't be there for, but I could feel my spirit touch it and taste it and hear it.

Trevor, in your prior work, you seem to be attracted to the nexus between the psychological and physical worlds. Does this collaboration represent a further development of this ongoing thread?

Trevor Powers: Always.Whenever I sit down to write anything it's like music is my form of prayer, and I say that in a very broad way. It's trying to communicate with that inner intelligence, the intelligence that's inside of us that we may never figure out, but it's a constant pursuit. That feeling of trying to make sense of what doesn't make sense, whether it be the world in general, or a more personal collision of feelings that you're just trying to put together.It's always that pursuit of the deep crevices in the brain that feel very unexplored. I feel like I could work on music for so many lifetimes and never explore all those surfaces.And that's the most exciting thing about it.It's nice that there's no end.

Ian, does this resonate with your own work?

Ian Strange: With my work, it's usually some form of poetic interpretation of architecture, like how to take the psychological interiors of spaces, or the intangible histories of spaces, and use forms of markings on these houses, to somehow shift these familiar spaces askew.

There are normally two aspects to these works. One is the very specific history of a site, an almost journalistic site history – the anthropological history of the site, which can be pretty absolute. But also, through working with an archetypal image like the home, you can start to deal with it as a broader metaphor, one of shelter and community and place, and everything else that this image is an index of. Even the notion of emotional shelter and safety that it can signify. There are very few things that you can do that resonate like this at a community level. Where you can show it back to the community it was made in, and then also show that same work around the world where, without knowing anything about that community, there's still a psychological truth and honesty to that work and an imagery that's somehow universal, that people can connect with. So, with those two aspects, I'm dancing between the psychological and the physical. Between the poetic universal read of a work and the hyper specificity of site and community.

Trevor Powers: The more poetic something is, generally the more others can attach themselves to it because there's not that specificity. When something's open-ended it's layered, and someone will always be able to find something in it. I think that was also what was so powerful about the work.

Is this specificity also part of gaining the respect or the trust or the engagement of the communities and families that were attached to the site?

Ian Strange: When you make work like this, it always starts from conversations and seeking permission to be there. That community involvement is a part of the project. But I think that for all my projects there's always a contradiction there because there's always a universal frequency where it also has a resonance devoid of context, devoid of site. You could show this work without telling anyone about the history of the site and it would still be largely affecting, just because of the power of the symbols we are working with. But it's also a real place with a real history and a real community, which gives us this other narrative. Those things can coexist, but it's a kind of contradiction I've become comfortable with in my practice.

Ian, when you first moved from suburban Australia to the urban metropolis of New York City over a decade ago, you were working as a graffiti and street artist under the mentorship of Ron English. Is there a connection here, in your ongoing focus on the resonance of ‘home’?

Ian Strange: It was a long while ago, but yes, I think coming from largely suburban Perth, Western Australia and then suddenly being in New York and connecting with graffiti and that whole urban centric scene had an impact. I arrived in 2009, and I was suddenly showing with Futura and Banksy and all these graffiti heroes of mine. They'd all been part of the first wave of that movement in the '80s and had been broke in the '90s, and then I was there for this most recent uptick in the 2000's, and it was that moment where that older generation gained recognition for a thing that they had built from scratch.

I was still very young. Ron English basically gave me Willy Wonka's Golden Ticket – he grand-fathered me into this movement, right at the end, at this upswing. For me, it created a moment for me to question, what were these artists doing in their 20s? What were they making that was new and unique at the time, that was legacy now? You know, Ron English is in his mid 60s, and he was now just starting to get proper museum recognition. So, it made me reflect on what is an artistic legacy was. What story are you telling over a lifetime? And I guess, for me, if you're going to tell the story over a lifetime, it has to come from an authentic place. So, as much as I loved that movement, there was something that didn't completely fit.

But I'm still really interested in the impact of marking in public space and that antagonism of graffiti and mark making. At the time, I'd studied film and photography, so both backgrounds started to coalesce in what became my practice now. I still like the idea that a public marking like graffiti could somehow by aesthetically changing a wall be perceived as damage, without actually functionally breaking anything. You can antagonise architecture, you can antagonise public space, with this idea of marking houses. People can perceive this is as an attack on the home itself and find it offensive but you're really only materially affecting the veneer of the house. You can paint back over it, but it somehow creates a psychological shift. I think that idea of how an aesthetic shift can create a psychological shift in the understanding of that space, and somehow reveal how vulnerable it is, psychologically.

Trevor Powers: Well yeah, because homes are everyone's most prized possession, that's the crown jewel. So, when you fuck it up, everyone's like, ‘what did you do?’

Ian Strange: But it's interesting because in reality, you're not actually damaging it. And that then leads into all these notions that people have written about for years, which is how much we load onto these objects and how they become these indexes of so much in our lives and how we understand ourselves. And of course, people don't logically think I'll just paint over that. They see graffiti as a visceral attack. I think that's super interesting. And that became a starting point for me.

Did notions of home become particularly resonant during the pandemic, when our homes became our whole physical world, and the rest of our lives became so immaterial?

Trevor Powers: From my end it definitely did, because home has always been the place that I come home or come back to sleep to with touring and traveling. I constantly had the opportunity and the drive to get out and I never imagined a world where everything would be shut down. That was something that I just never saw ahead. And so, when that was the case, and leaving home wasn't an option, even going to the grocery store was sketchy because you didn't want to get sick. So, to just be home and have that be the only place that you are had a comfort to it because you knew everyone was in the same position. You're going through it together. But being home also could drift towards the darkness and it could feel like a prison. So, for me in this work I was trying to explore all of these places.

My way of leaving the house was through movies. I have this this old VHS player in my room, and I would put it on mute. There was just something about what would come off the screen that informed my musical choices. I got a lot of my inspiration through the work of Andrei Tarkovsky. I watched his movie Mirror so many times when I was working on the score for Dalison because there was something about the spirit in that movie that somehow fit – the textures and the colours that he had worked with. I don't know what it was, but I the more I focused on movies like that, the more I felt like the score was taking shape.

Ian Strange: I did not know you were watching that while composing. That's fantastic. When we were first messaging, I was actually re-reading Tarkovsky's ‘Sculpting in Time’. I love the way he writes about poetics in cinema, it's informed nearly everything I do.

My lockdown was a different experience. Western Australia was locked off from the rest of the world, largely without Covid. It was like an island, as in literally if you left during the pandemic you couldn't get back in. That was a very surreal situation to be in. I was lucky in many ways, it's one of those situations where you certainly can't complain. But it was claustrophobic in its own way.

The work was born during our initial conversations right at the peak of the first round of global lockdowns when everyone was still in their houses, myself included. The work's subject is an isolated home – it's the last house standing in a former suburb. It's a house that is deeply vulnerable and set for demolition. And I think there was something about those layers of vulnerability in the isolation of these spaces, and a literal and figurative isolation during that time as well. When a project happens it always feels like there's all of these points of reference and they’re all coalescing. And when we started, it all felt like the timing was perfect.

It felt almost too perfect. There was this moment where all my plans were off, but then I came back to this isolated home in Western Australia that was still there six years after I'd first seen it. I was blown away that it was still there, and it was just six months away from demolition. I was trapped in Perth and I was looking for a project to work on with Trevor. And the residents and former neighbours were so supportive of the work. I think the context of it being made at that time gives it a resonance. But I my hope is that it's a work that you could still talk about in 10 years’ time. We have certainly not explicitly seen it as a pandemic work or a pandemic response.

Trevor Powers We would have had to work the same way anyways because we live across the world from each other. So really, Covid or no Covid, the process would have been relatively the same. But it would have been a little smoother as far as the timeline goes. We had to bump the timeline multiple times because of Covid. When I was first working on the music, Ian said I need the music in two months. So, I did all the music in two months because that was the timeline we were sticking to. It was actually really great for my process, because it forced me to be in this world and not do anything else because it was so important that I get it done. After that we had way more time. But if I had known that we had more time, I don't think it the music would have been what it turned out to be. So, I'm thankful.

Ian Strange: Yes, we were told the timeline the house would get demolished on. And then there was a Covid outbreak, and everything got pushed back. Initially we thought we’d have to make it really fast and then it slowed down. So, the work happened in spurts.

This is your first collaborative work together. Are you planning to work together again?

Ian Strange: It's something I'd love to do again somewhere as a concept. I think it's something we could revisit – not this exact work, but the notion of responding to architecture or site and creating a work like this. For this project, we had a one-off performance just for that audience and then it was filmed. But I like the idea that this might be something that could sit within a bigger festival program meand city, where you find a site, create an installation and an original piece for that site, and it becomes a work that you come in pilgrimage to, to visit. These sorts of homes exist all around the world. I would love for a brave commissioning festival curator to curate a version of this work. I think that would be amazing.

And then we could think about how that music is performed. What does that look like, does that mean that it would be a live performance? There's an underlying concept here that I'd love to expand if Trevor is not sick of me.

Trevor Powers: I'm definitely not sick of you.It's funny because I mean really, if you count the number of conversations we’ve had other than email and DMs this is maybe number six?

Ian Strange: Yeah, we’ve never physically met each other before.

Trevor Powers: It's crazy. It's all been screen based.

Ian Strange: Even though we haven't met in person, I feel like there's an intrinsic alignment in terms of value and approach and aesthetics and trust here. It's certainly been a dream collaboration.

dalisonproject.com

Photographs 1–3 ©Chris Gurney; photographs 4–7 ©Ian Strange.

Ian Strange is a transdisciplinary artist whose work explores architecture, space, and the home. His practice includes multifaceted collaborative community-based projects, architectural interventions and exhibitions resulting in photography, sculpture, installation, site-specific works, film, documentary works, and exhibitions created around the world. His studio practice includes painting and drawing, as well as ongoing research and archiving projects. Strange is best known for his ongoing series of suburban architectural interventions, film, and photographic works that subvert the archetypal domestic home. Strange's works have been exhibited extensively in spaces such as The National Gallery of Victoria, Canterbury Museum, The Art Gallery of Western Australia, Art Gallery of South Australia, Whitewall Galleries, Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, ThinkSpace, MCA, The Queensland State Library, Allouche Gallery, Standard Practice Gallery, Strychnin Gallery Berlin, and Fremantle Arts Centre; as well as at arts festivals including Underbelly, PUBLIC, Nuart, Auckland Festival of Photography, and SPRING/BREAK 2017. In 2017, ABC TV released “HOME: The Art of Ian Strange”, a six-part documentary series looking at Strange's career and work to date. Strange has spoken and lectured widely about his practice, including at Parsons School of Design (2014), Columbia College Chicago (2017), TEDxSydney (2018), RMIT University (2019), and Harvard Graduate School of Design (2020).

Trevor Powers is an American musician, producer, and composer based in Idaho. He began recording music in 2011, releasing a trilogy of albums under the moniker Youth Lagoon before announcing the end of the project in 2016. Two years later, Powers and a handful of contributors retreated to Sonic Ranch, a residential studio complex in Texas in the middle of a 2,300-acre orchard. The result was Mulberry Violence – the debut album under his birth name. The six-week tracking process consisted of fusing together textures, arrangements, and programming created at the ranch with poetry he had written over the previous two years. The album was mixed in Los Angeles by frequent Beyoncé collaborator Stuart White. In 2020, after a severe panic attack, Powers took to a cabin with a piano near Idaho's Sawtooth Mountains. Here Powers made the album Capricorn. As Quinn Moreland notes on Pitchfork, ‘Like a heavily tattooed modern-day Thoreau, [Powers] sprinkles the record with recordings of raindrops, streams, and thunderstorms, reminders of the symphony that the natural world offers us for free.’ Capricorn paints a world of melancholia and unsettling beauty. Powers’ field recordings, classical motifs, and software sculptures don't stop time; they examine it like a beetle under a microscope – exposing that the extraordinary is often hidden in plain sight. ‘From the minute we wake up, we're in a trance,’ he says. ‘This is music for our digital coma.’