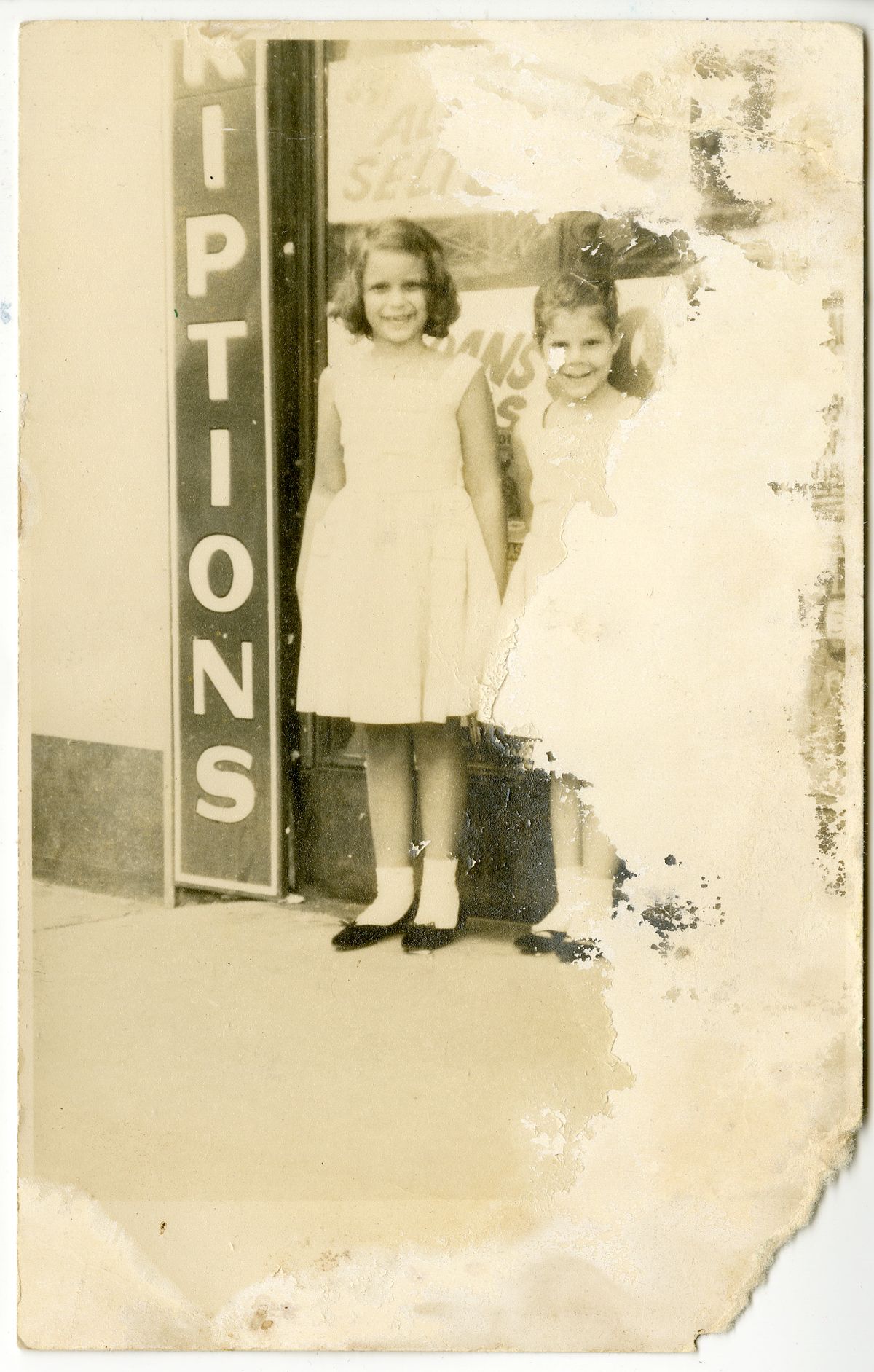

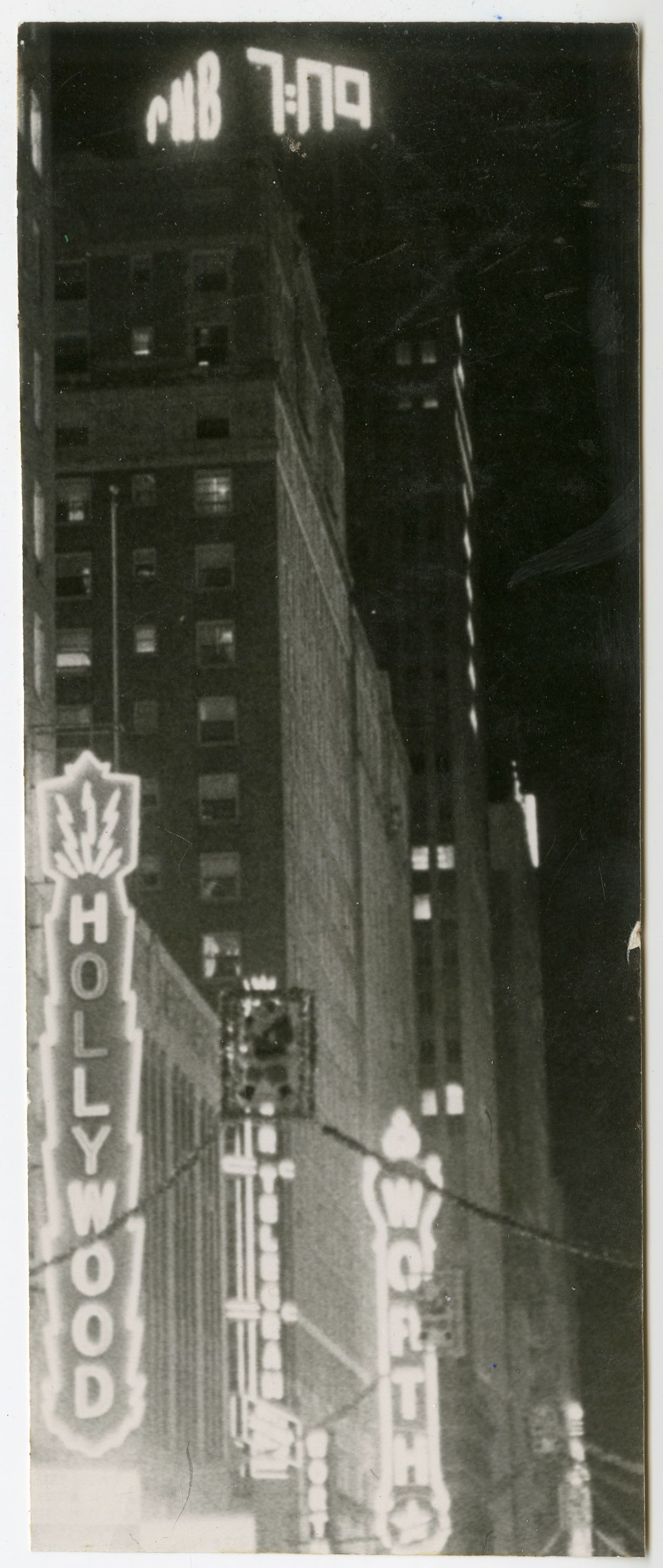

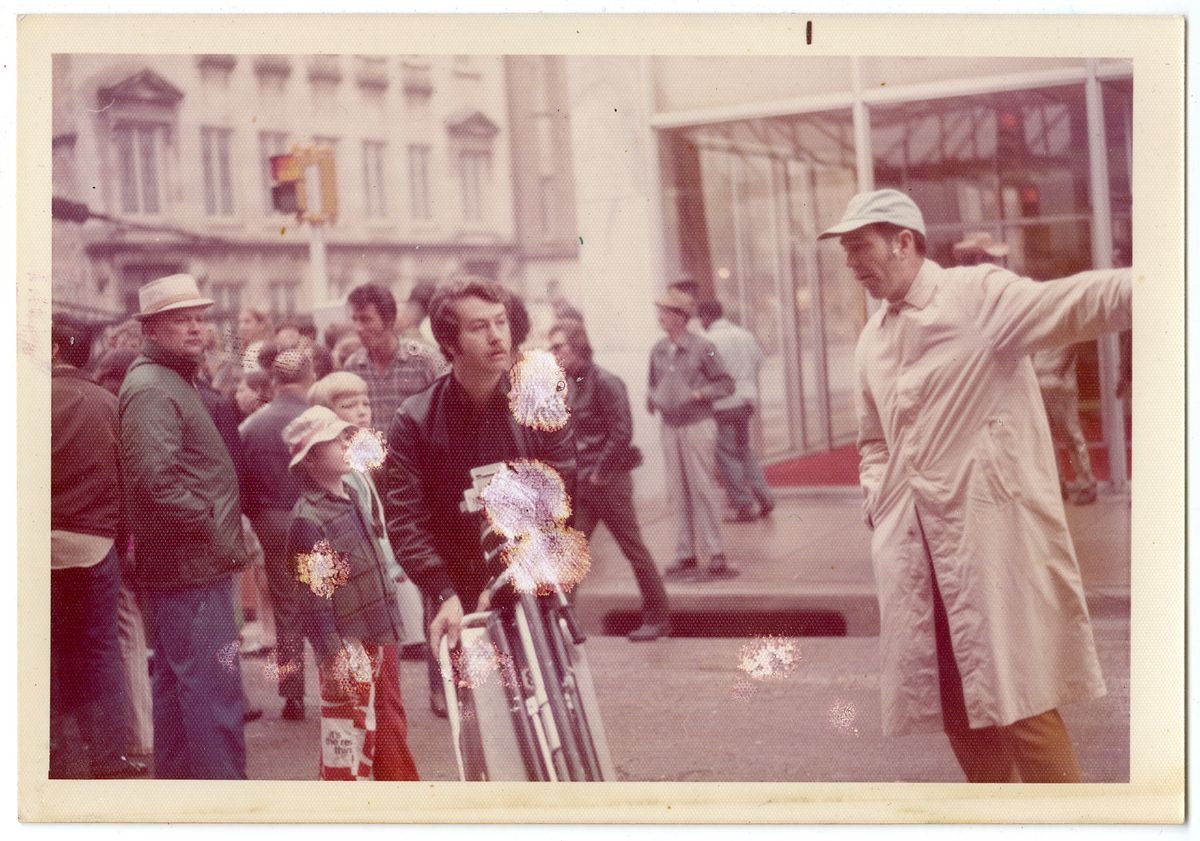

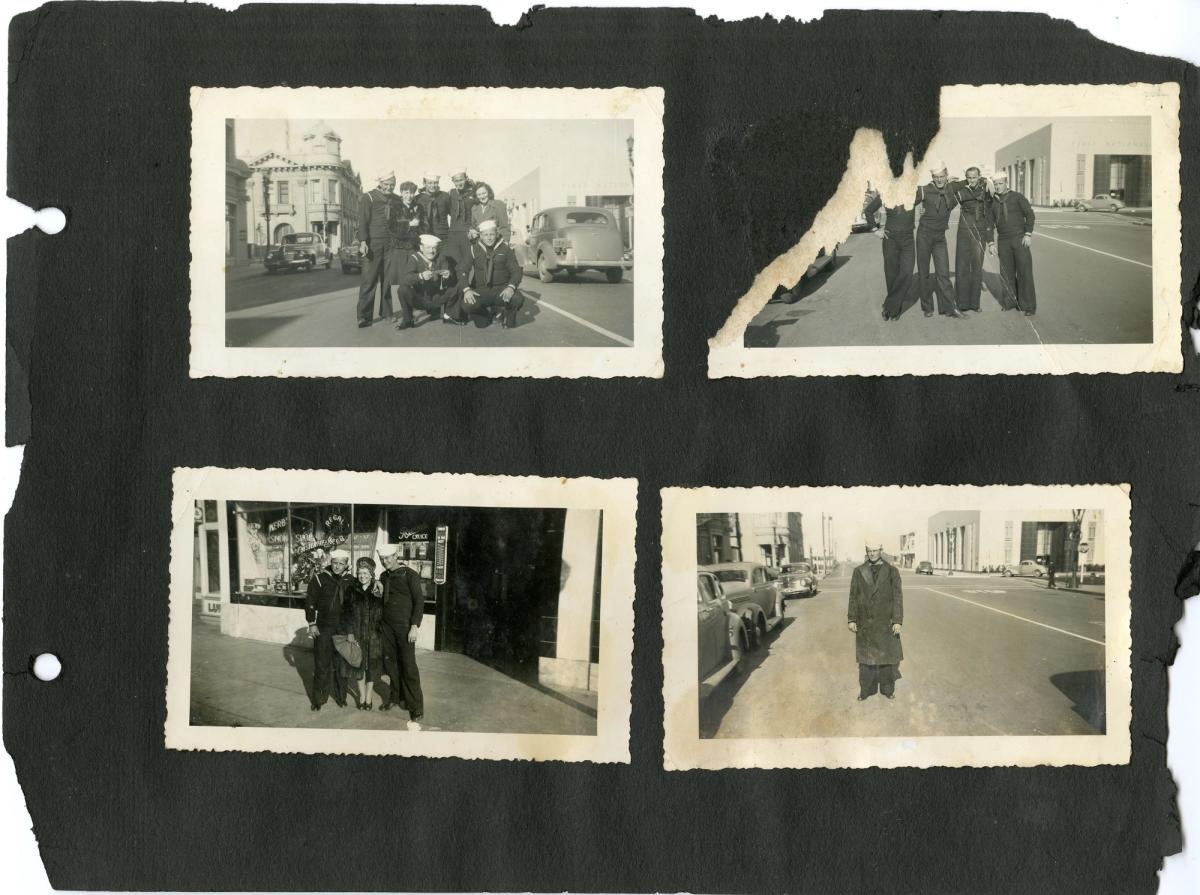

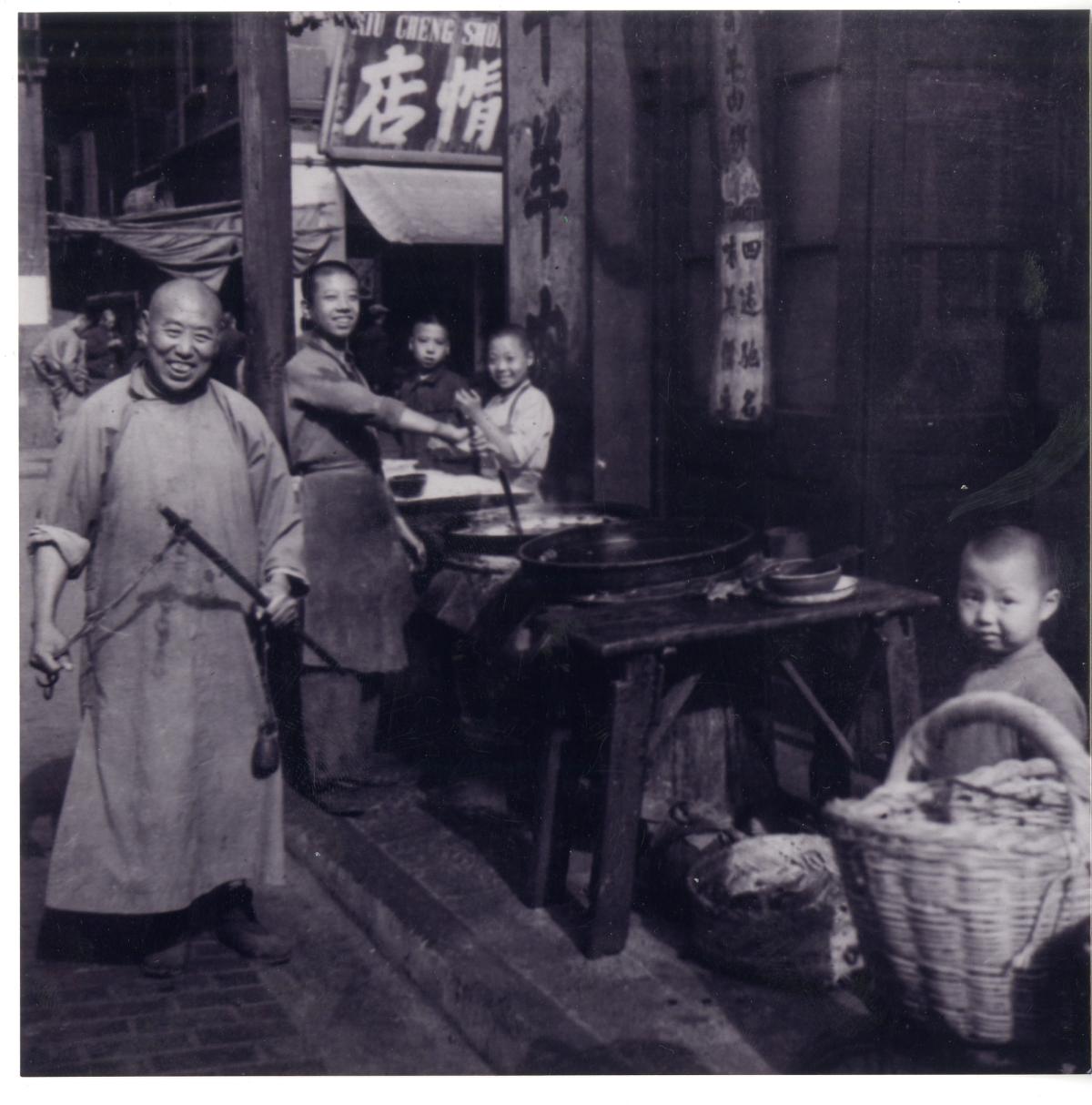

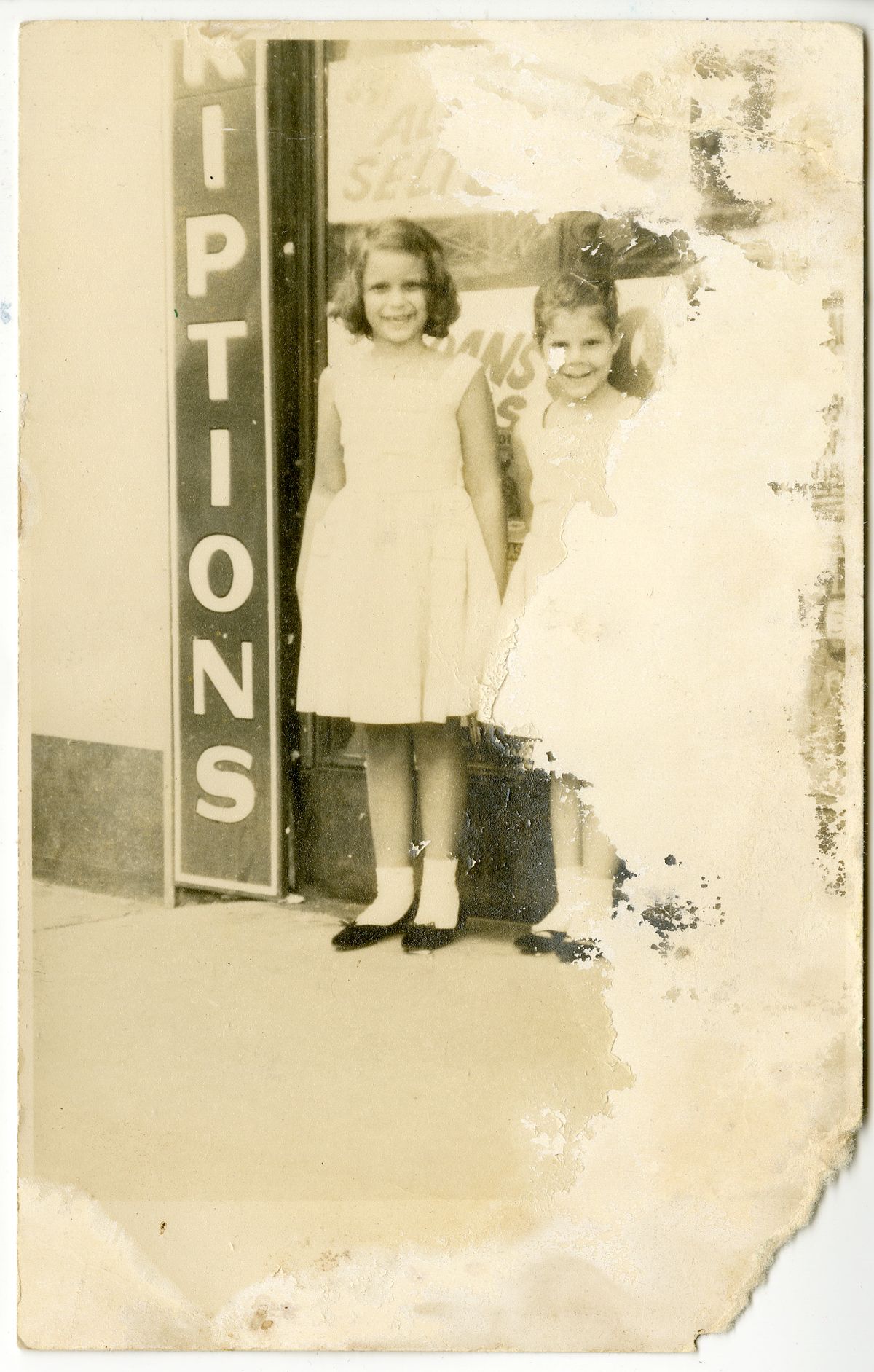

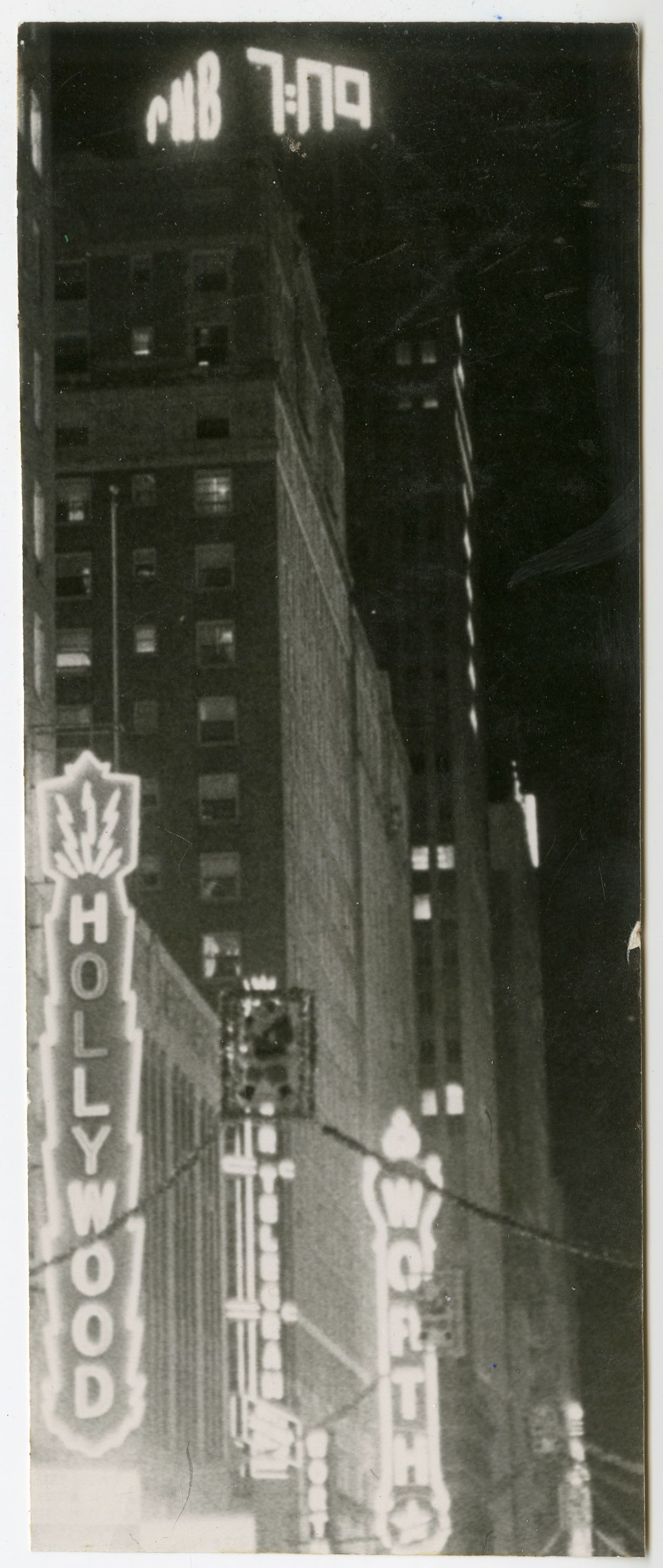

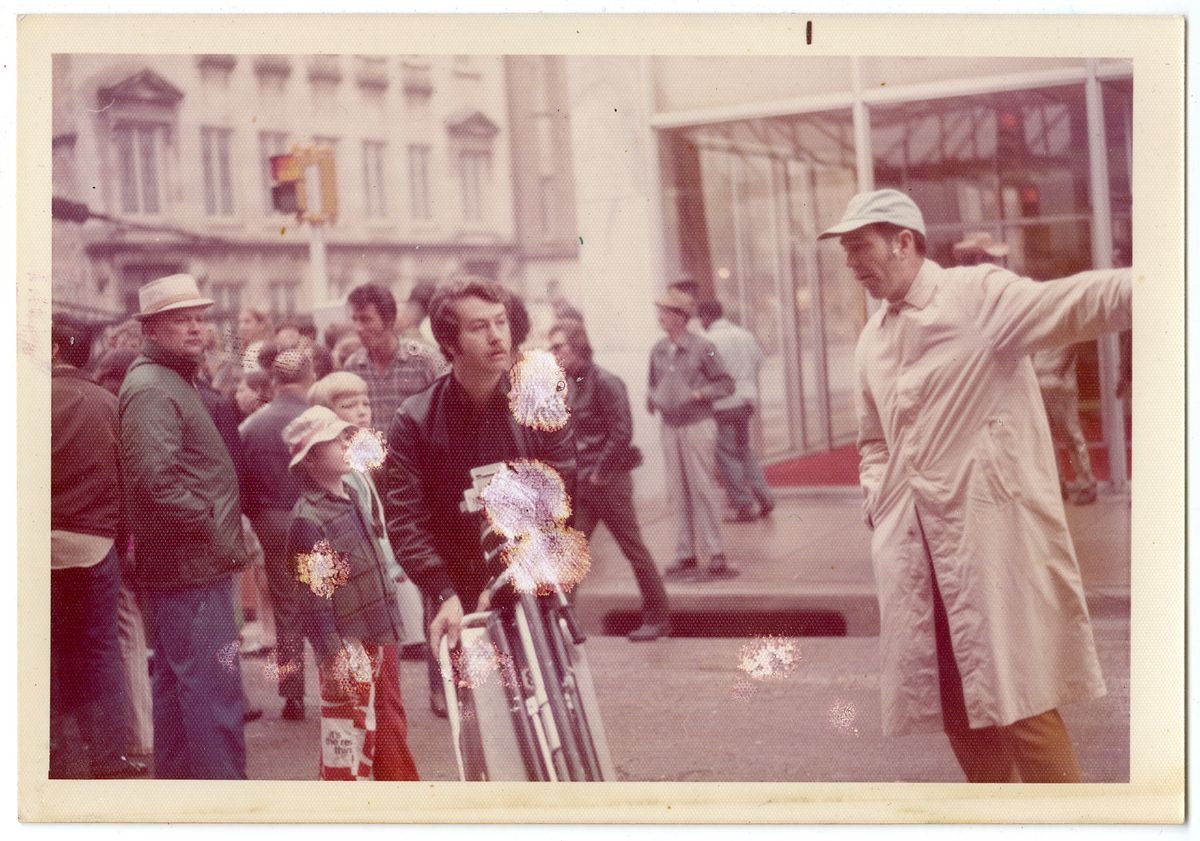

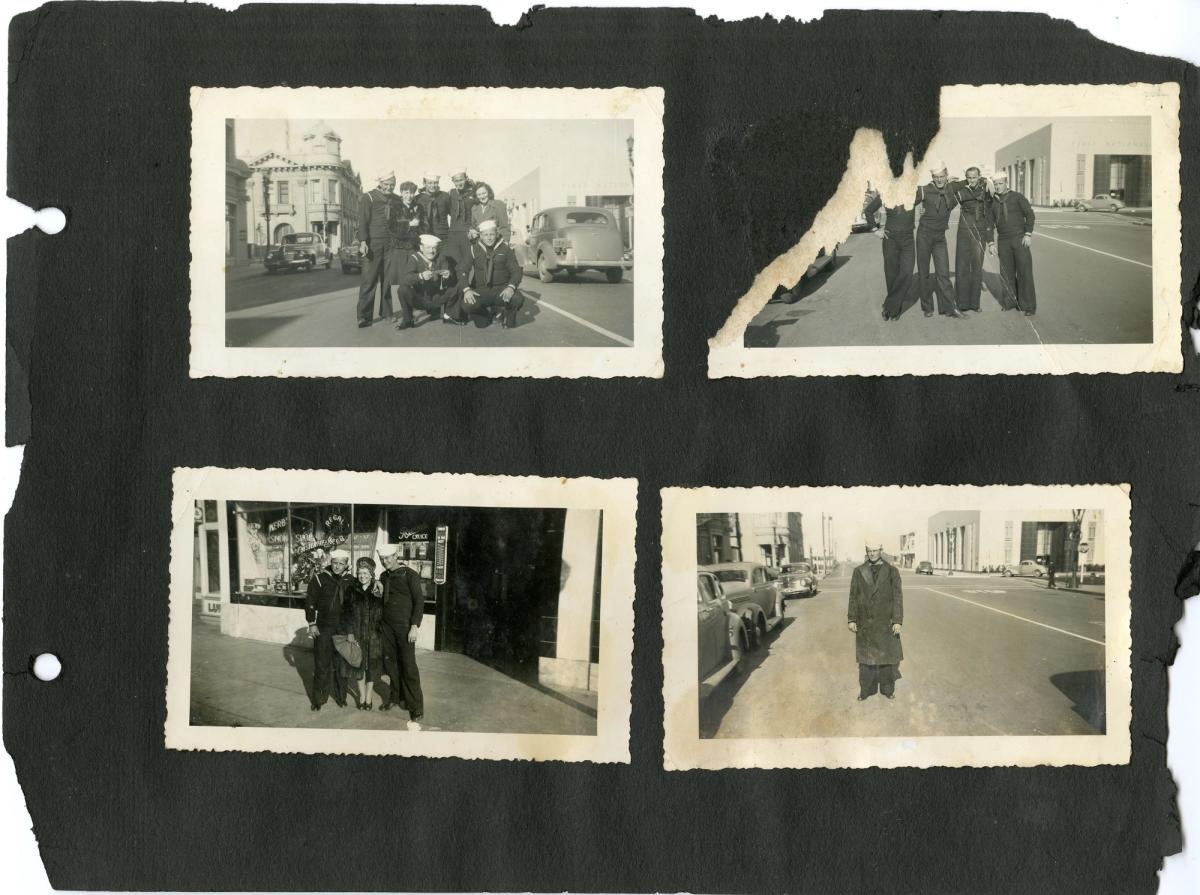

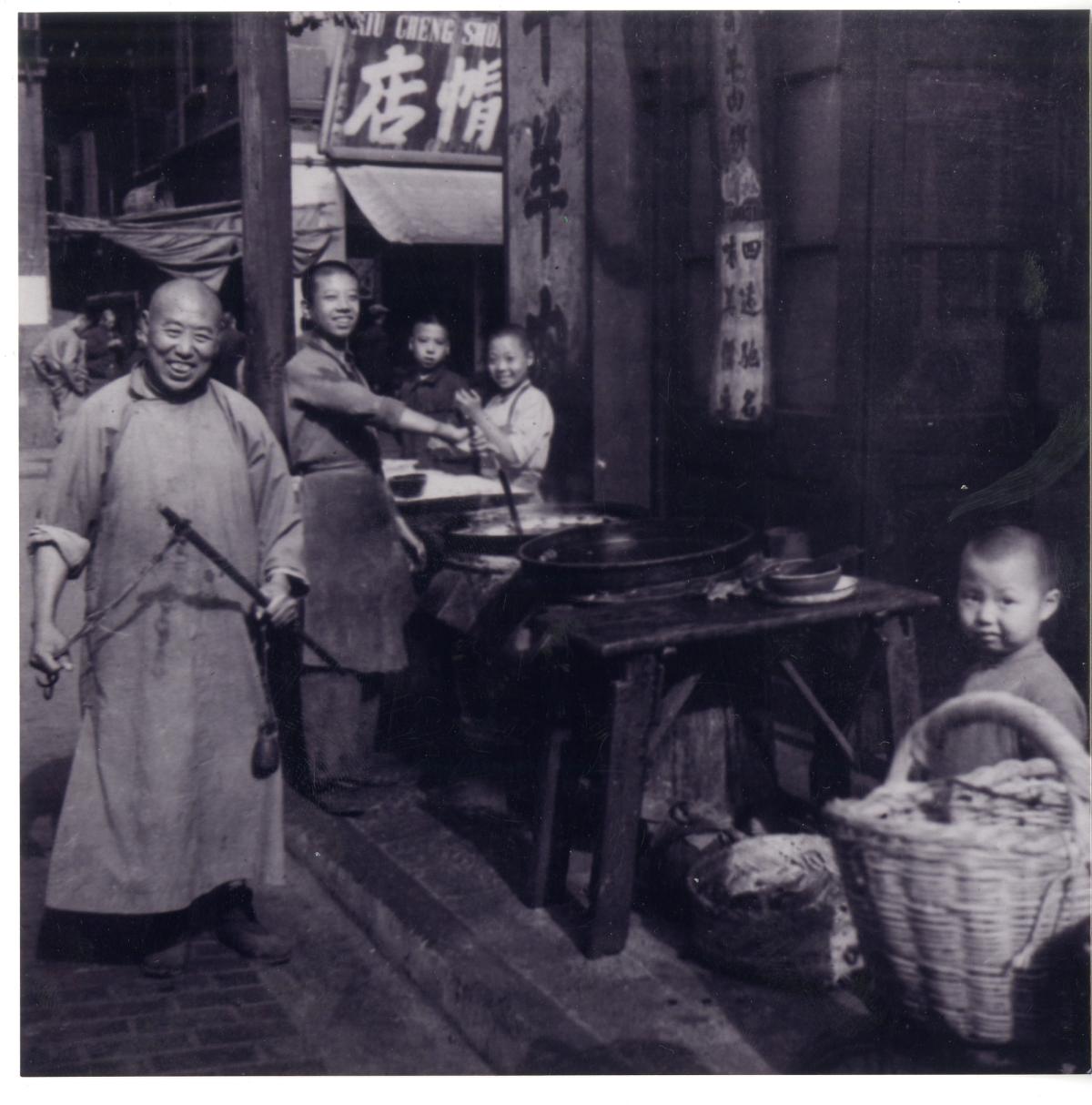

We inscribe urban art on walls, etch it on windows, perform it in public space, hide it in alleyways and underpasses, glimpse it on passing freight trains. We also discard it in waste bins and trash bags. Digging through these bins and bags unearths cardboard boxes, food, clothes – the detritus of everyday urban life. It also reveals a distinctive sort of urban art: the photographic evidence of this everyday urban life past and present. Parents die, couples split, attics and basements get cluttered and then cleaned, memories get digitised – and as part of these processes, old photographs come loose from their origins and find their way into the waste stream. The intended subject of these photos is often a parent or a child, a holiday or a birthday; but the background subject is often the city itself, the particular urban milieu in which such photographic moments unfold. Other times the subject is overtly the city, or some other city, worth noting visually when animated by an unusual event, visited for the first time, or encountered as a long-imagined destination. Scattered around the city, secreted away in its refuse, are images of the city. Lost, they wait to be found.

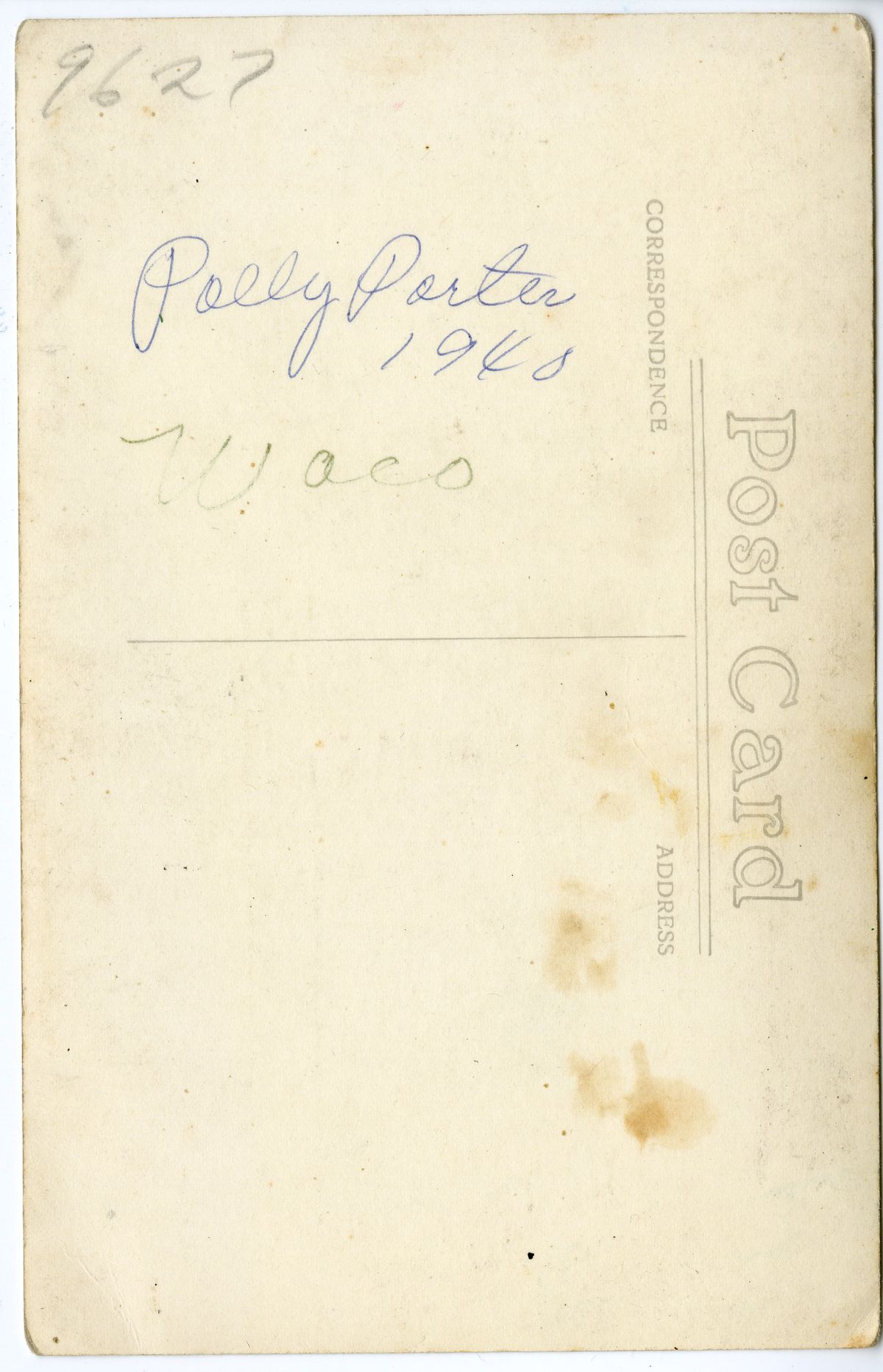

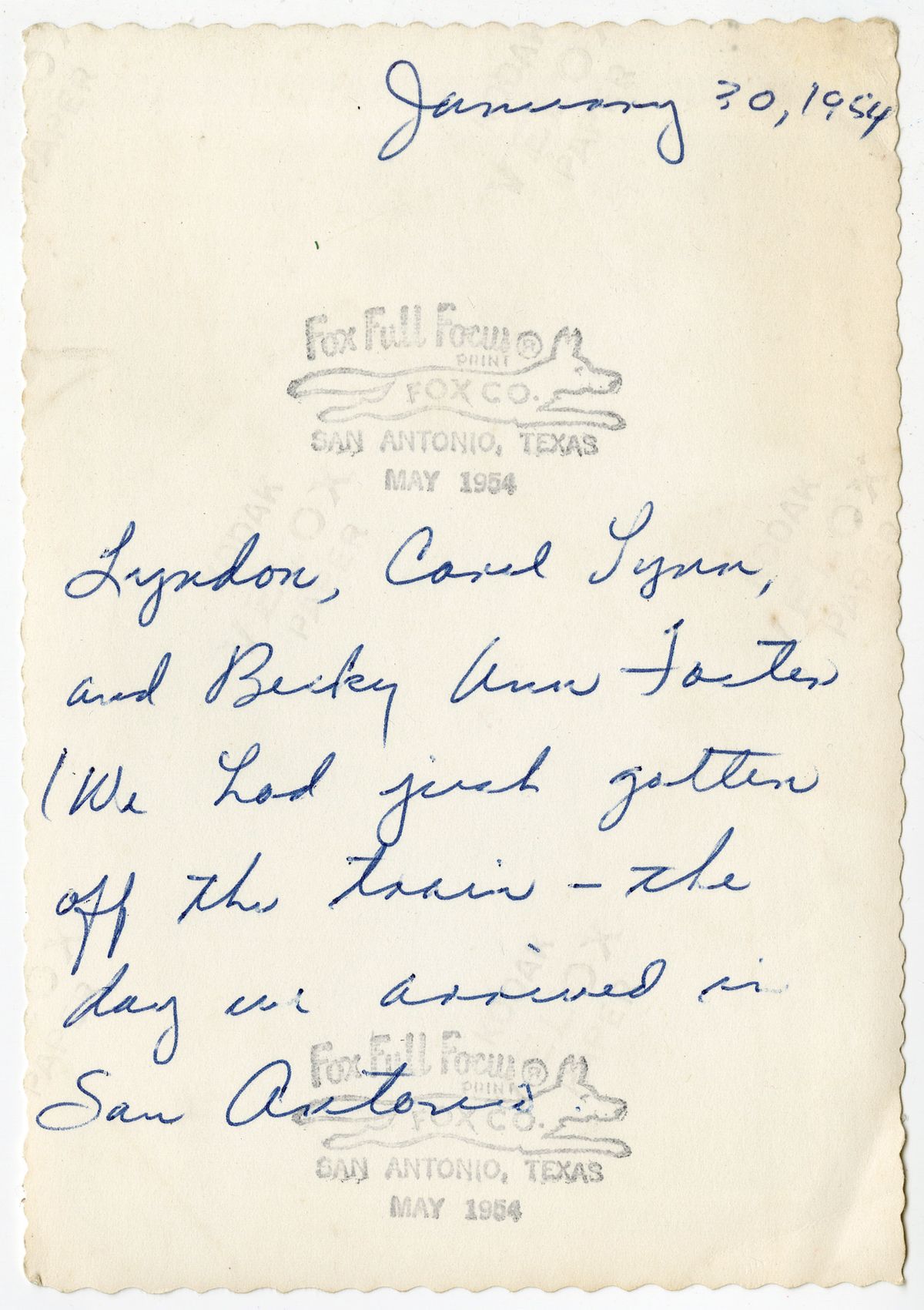

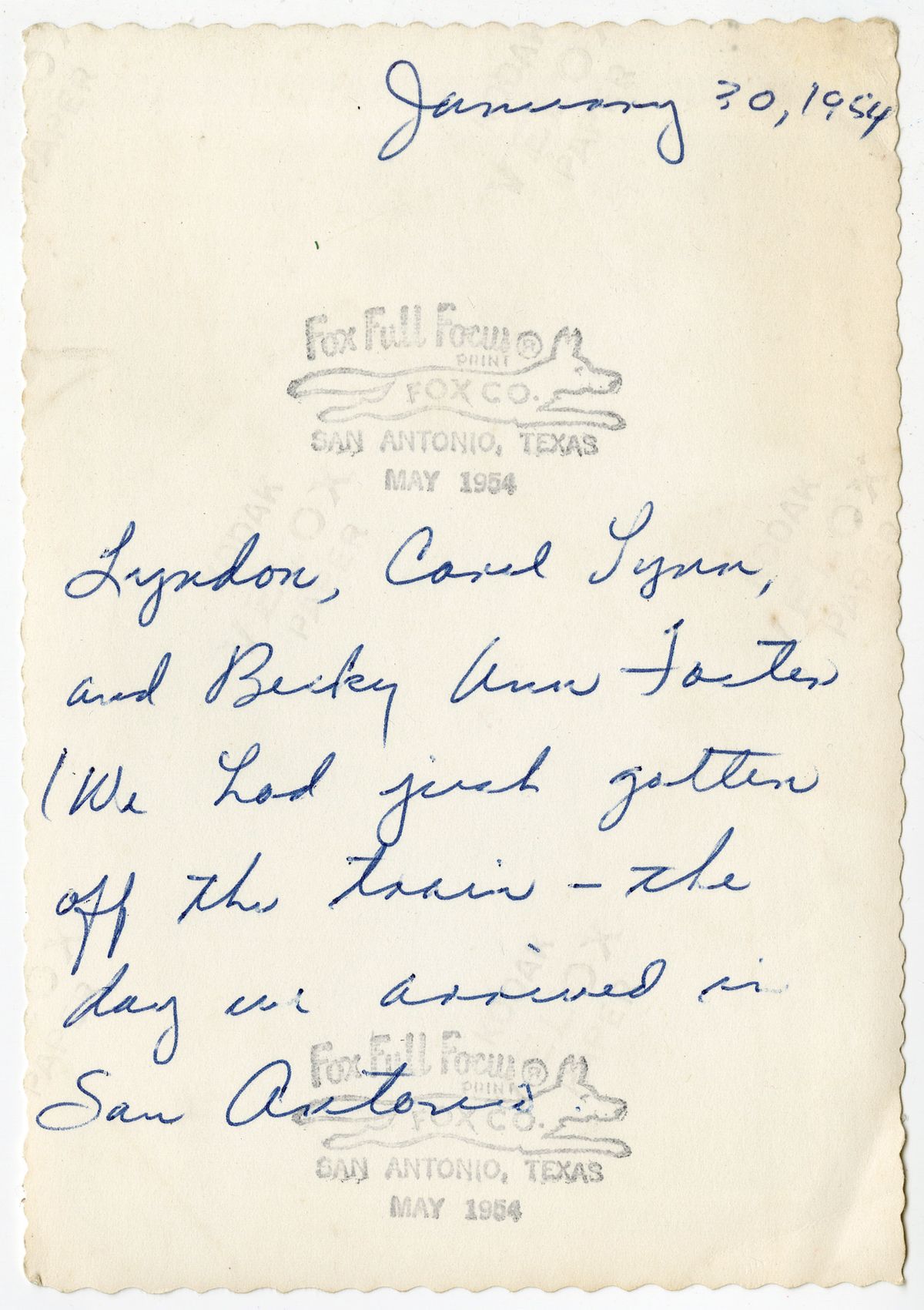

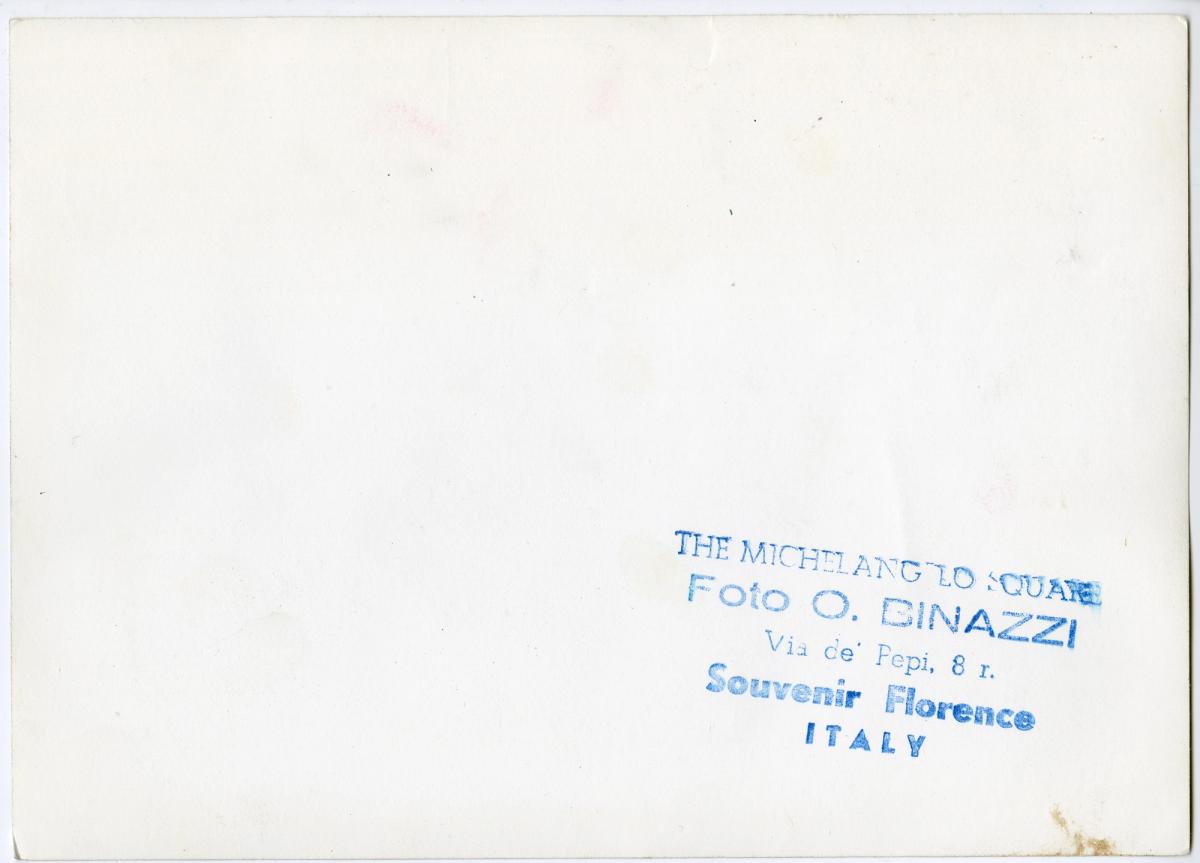

Everyday urban life in turn works on these photographs, marks them, wears on them. The physicality of the photographic print makes it available for written reminders and descriptions – sometimes names or arrows drawn directly on the photograph itself, other times names, dates, or locations inscribed on the photograph’s flip side, or back-of-the-photograph notations recording something of the technical process by which the photograph was developed. The photograph’s fragile physicality also leaves it susceptible to subsequent deteriorations; lost photographs often feature stains, tears, and distortions, some acquired prior to the trash bin, others while in it. The city illustrated becomes the city annotated.

Taken together, such photographs construct a secret archive of city life defined as much by what it omits as by what it includes. The photographs shown here were scrounged and collected from the trash bins of ‘nicer’ neighbourhoods in a large Texas city, for example, and so they suggest the inequitable intersections of race and class that situate certain groups in such areas and systematically exclude others from them. But if such photographs archive particular patterns of urban life, they unravel others. Collectively, they produce a dislocated urban history of visible ghosts and invisible intentions, a disorienting dérive through other lives, other times, and other places. They build yet another city within the city, this one pieced together from image, loss, memory, and imagination.