Urban creativity is an umbrella term for a range of activities within, or in direct relation to, the city. An important characteristic of situated urban creative practices is that they push legal, moral and cultural boundaries by intervening and exploring alternative ways of using, producing, experiencing, and understanding the city.

In thinking about urban creativity, Greek street art has undeniably opened new ways of understanding and experiencing the urban fabric of everyday life, considering the economic and sociopolitical circumstances within which they are placed. Street art (of resistance) as Elias (2014) describes it, has the unique ability to fuse aesthetics and politics, offering a new form of situated participation in urban space and fostering the emergence of a prolific culture. Artists, as he argues, use playful and self-reflective sets of semiotic strategies to engage their audience.

In short, street art practitioners and activists claim their right to participate in the visual construction and reproduction of the Greek ‘publicly accessible space’ (Bengtsen, 2018). The visual environment is ever changing, considering the ephemeral and dynamic nature of street art as well as the economic, political and cultural contexts of these situated practices. Thus, it may elucidate many occurring sociopolitical and cultural displacements. Street art is broader in scope than graffiti, and includes a wider array of techniques, and aesthetic and expressive media. To a large extent, it is an intentional spatiotemporally oriented, ephemeral, entertaining (playful), and cross-cultural, but also socioculturally conventionalized, phenomenon. Relevantly, street art is typically built on the inter-play between two universal and interacting semiotic systems – language and depiction – and is thus a form of polysemiotic communication (Stampoulidis et al., in press).

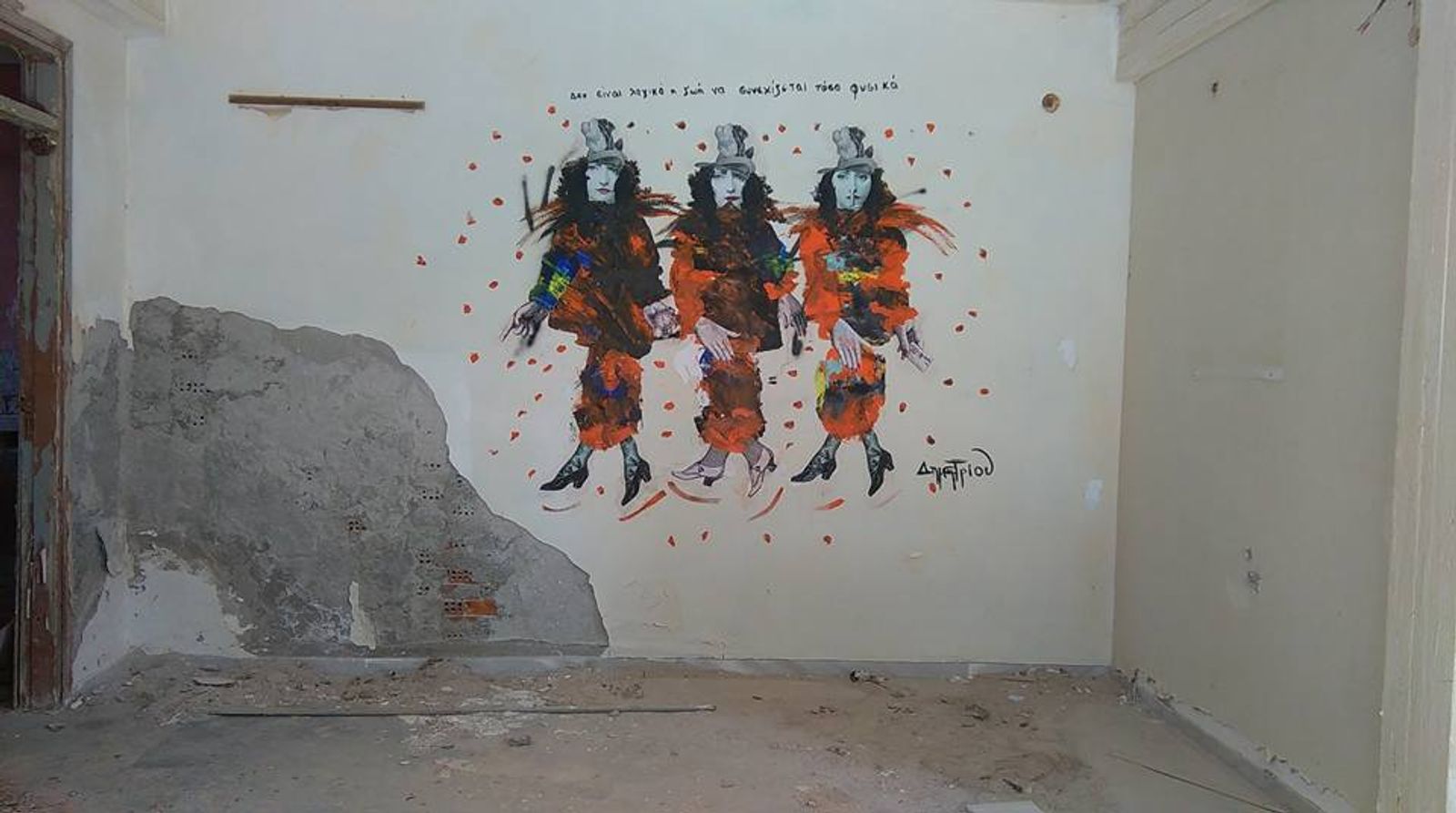

This photo essay focuses on a specific kind of street art practice in Greece, namely a number of visual interventions in abandoned buildings, and especially the Xenia Hotels Project initiated by the artist Anna Dimitriou, as communication tools for addressing sociopolitical issues in interaction with the spatiotemporal contextual surroundings (Avramidis and Tsilimpounidi, 2017; Chaffee, 1993). In other words, the present enquiry considers social, cultural, and political activist aspects of Greek street art, problematising the relationship between both cultural and creative activities in abandoned urban space.

Anna Dimitriou, an Athens-based activist, street artist, and urban practitioner only recently started painting walls in abandoned buildings and on the streets of Athens using the typical decorative technique of decalcomania, which is a fusion of different materials including paint-filled engravings and prints. As she has argued in a recent interview conducted by Stampoulidis in September 2018:

It is a good thing our city is full of empty walls that anyone can express him/herself on. Greece is like a notice board that anyone could post their ideas on […] All this began a year and a half ago, when we found out that my father is sick. I started looking at old photos of him, you know the pink ‘80s vintage kind, trying to recover him from the summers of my youth. Those lovely Greek summers that just do not exist anymore. Somehow, like all those abandoned buildings […] It felt like my father was a part of this demolished, lost world and I somehow tried to recover them both. I began the Xenia Hotels Project, in order to give them back life. To make a fuss in order for people to remember them.

Xenia Hotels was part of a state programme which aimed to develop tourism throughout Greece from the 1950s to the 1970s as one of the main priorities for the recovery of the Greek economy after World War II. However, in the late 1990s, Xenia Hotels were abandoned. Despite this, for many Greeks they (still) carry a significant emotional load. Although abandoned, they remain architectural masterpieces of the historical past of Greece, built on the most spectacular places around the country.

Xenia Hotel, Spetses, April 2017

Xenia Hotel, Parnitha, May 2017

Xenia Hotel, Kalabaka, Meteora, May 2017

Xenia Hotel, Andros, June 2017

Xenia Hotel, Sparta, August 2017

Xenia Hotel, Nafplio, April 2018

Anna Dimitriou strongly believes that Xenia Hotels may be transformed into cultural beehives by hosting cultural activities and other similar services and institutions:

I put a mirror on their faces. I make these forms that I call ghosts. Because they are forms from an old world that no longer exists, since we have demolished it. However, I recreate it. Ghosts of people who passed through these hotels. On the other hand, the angels in the Xenia Hotels are the guards, who potentially take action to rejuvenate. They are modern angels, detached from angel hierarchies and divisions. They do not have sex, as you know. They are angels who protect these buildings until they give back the life they have promised. In most of my frescoes I meet the head of Piero Fornasetti’s muse from those ornamental dishes. The Xenia Hotels Project highlights the problem of cultural heritage management in Greece […] Architecture is a kind of cultural heritage and social memory (Interview by Stampoulidis with Anna Dimitriou, September 2018).

Georgios Stampoulidis is a PhD candidate in Cognitive Semiotics at Lund University. His research interests are in the fields of semiotics, pictoriality, figuration, polysemiotic communication, and urban creativity. His work focuses on street art as a site of cultural production and political intervention. His most recent publications are ‘The black-and-white mural in Polytechneio: meaning-making, materiality, and heritagization of contemporary street art in Athens’ (Street Art and Urban Creativity Scientific Journal, 2018) and ‘A cognitive semiotics spproach to the analysis of street art. The case of Athens’ (International Association for Semiotic Studies, 2018). Georgios Stampoulidis is co-editor of the Public Journal of Semiotics (PJOS) and research fellow at the Pufendorf Institute for Advanced Studies, Lund University (Urban Creativity).

- 1

Urban creativity is an interdisciplinary research theme and is hosted by the Pufendorf Institute for Advanced Studies at Lund University, Sweden: https://www.pi.lu.se/en/activities/UrbanCreativity.

- 2

For a discussion about street art and graffiti terminological issues and various conceptions within recent street art and graffiti scholarship see Ross et al., (2017).

- 3

All photo captions are based on text provided by the artist.

- 4

All selected photographs have been provided by Anna Dimitriou and are displayed on Google maps showing

their geotagged locations:

https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/edit?mid=1s3ZGCn7kR7EsnFVsJXRsgGziV8BYVw&hl=en&ll=39.93728066698674,22.3313404181492&z=7

Avramidis, K. & M. Tsilimpounidi (Eds.). 2017. Graffiti and street art: Reading, writing and representing the city. London: Routledge.

Bengtsen, P. 2018. Street art and the nature of the city. In P. Bengtsen, M. Liljefors & M. P. (eds.),

Bild och natur, 125–138. Tio konstvetenskapliga betraktelser, 16.

Chaffee, L. G. 1993. Political Protest and Street Art: Popular Tools for Democratization in Hispanic Countries. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Elias, C. 2014. Graffiti, social media and the public life of images in the Egyptian revolution. In B. Hamdy & D. Karl (Eds.), Walls of Freedom. From Here to Fame publishing.

Ross, J. I., I. Jeffrey, P. Bengtsen, J. F. Lennon, S. Phillips & J. Z. Wilson. 2017. In search of academic legitimacy: The current state of scholarship on graffiti and street art. The Social Science Journal 54(4). 411–419.

Stampoulidis, G., M. Bolognesi & J. Zlatev. In press. A cognitive semiotic exploration of metaphors in Greek street art. Cognitive Semiotics 12(1).