We are the Political Stencil Crew, a group of artist-activists based in Athens. Since 2014, we have intervened in public space with political stencils and graffiti, both in Greece and abroad. Our priorities are social and political commentary, practical commitment to social struggles, refugee issues, and anti-fascism. Our target is the state’s repression, fascism, and sexism, and the austerity policies that have been violently applied in Greece in recent years.

We treat our field actions as unarmed military operations. We operate in public space, in a ‘hostile’ territory supervised by the authorities: we operate under bridges, on private walls, banners, banks, electricity boxes, and public buildings – any surface that offers a direct view to passers-by, passengers, and drivers. Each case is separately considered, taking into account the peculiarities and factors that can cause complications. ‘Our strong cards are speed and time.’ (Lawrence, 1927: 37).

When necessary, we take precautions against the authorities. We often pretend to be cleaners or groups of volunteers cleaning the city. Whatever precautions we take, we know that ‘a properly started operation is bound to fail if it lacks determination. Instead, hesitation and fear will be present. The determination of the people involved is the secret of a successful action, whether it is simple or complex.’ (Marighella, 1985: 50–51).

Our actions reveal elements of a guerrilla war without ammunition, small rehearsals for war in an urban environment. Political and social events are the fuel that drives the team. They trigger group discussions and the creative process on the basis of which the group then intervenes in public space with multiple stencil works. The works are also released on social media so as to encourage interaction with and awareness of these issues.

Our work draws on cognitive tools from the field of visual literacy. The images we use often invoke a narrative, based on the influence of particular events in society. There is a fundamental difference between images in which those depicted look directly at the viewer and images in which those portrayed do not. For Halliday (1985) the gaze of someone who is depicted ‘requires’ the viewer to enter into some sort of imaginary relationship with that very person. In political stencils, the subject often looks straight at the viewer, urging them to stop and think, if only for a moment (Figure 2).

The people depicted in our graffiti artworks are dead but not forgotten. We believe that not all of the dead pass into the oblivion of history. We therefore also classify our work as ‘memorials’, as we aim to represent and remember the victims of the unconquerable war that rages in our society – all persons that were targeted because they represented a kind of threatening nonconformity: those who were lynched because of their sexual orientation (Figures 3 and 4); those who were killed for supporting a particular football club (Figure 5); and those who were murdered for being active anti-fascist hip hop artists (Figure 6).

We use a basic colour palette – black, red, gray, and white without hues. Our stencil technique and the serial reproduction of our work on multiple walls refer directly to Andy Warhol’s pop art with a basic, noticeable difference: for us the content exceeds the technique, the means serve the purpose and not itself. In the case of pop art, the seriality of the reproduced object weakens the content, which for Warhol was mundane and inconsequential in any case (think of his images of Marilyn Monroe, Mao Zedong, Campbell Soup, etc.). As Warhol stated, ‘I wanted to paint ‘nothing’. I was looking for something that was the essence of ‘nothing’, and I found it.’ (Warhol quoted in Belle, 2007: 430). The means is the purpose in pop art; unlike in our own work, where it is not used for or against an ideology.

The verbal text framing our work is usually beneath, to the right, or above the subject. Words have a syntactical role and mediate, but do not merely provide information (e.g., name, place, event) but also work to create some sort of emotional appeal.

The messages that complete our stencils contain dialectical references to cultural beliefs and moral codes. In figure 2 the text, ‘killed by leventes’ reworks the word ‘leventes’, or ‘lads’. A good lad is conventionally regarded as ‘straight, honest, and dutiful’ (Bampiniotis, 2004: 570). Here, ‘leventes’ is transformed linguistically to stand for a modern version of patriarchy, homophobia, and a widespread violent attitude against those who are ‘weak’. Vangelis Yakoumakis, who is depicted in this artwork, committed suicide after long-lasting homophobic abuse and intimidation by his fellow students. However, sometimes the content of our work has a more playful character. In the case of the ‘best is yet to come’ project, the image took the same form as the building. The composition was codecided; we thought that the ideal ‘shocking’ object for the horizontal layout of the metal banner would be a horizontal erection. The text followed the form, framing the erection with the phrases ‘the best is yet to come’ and ‘blessed’ (Figure 7).

This work was painted on the roof of an old facility belonging to a 120 formerly associated factories located in Ekali on the outskirts of Athens, along the highway leading to Lamia. We chose this location for its easy access, the fact that we could work there without any obstructions, and the clear view of the building from the highway.

On the opposite side of the building is a huge area containing department stores – a no-man’s consumption land, which includes food store chains, toy stores and consumer electronics retailers. Our goal was to capture the attention of the people who visit this consumption zone on a daily basis – those who do not tend to share the financial problems common to other citizens, as they reside in Ekali, one of the most affluent suburbs of Athens.

In addition to shocking the middlebrows and disrupting their shopping excitement, the work was intended to make a bitter comment about the future, a comment on the fragile ‘prosperity’ of Greece. This prosperity goes hand in hand with false hope, harsh repression, the decomposition of society’s networks, and the country being placed at the mercy of world financial markets. Greece is a country which sees 35% of its youth labour force unemployed, which suffers from serious brain drain as hundreds of thousands of young people have sought their fortune elsewhere, and in whose waters thousands of migrants have drowned trying to cross the Turkish-Greek border situated in the Aegean Sea. Moreover, Greece is at the tip of NATO’s spearhead and, geographically, is a land which finds itself right in the middle of a vicious rivalry between imperial powers.

For three weeks, we intervened for a few hours every weekend until the project was completed, knowing at the outset that it would not remain untouched for long. As it turned out, at least one consumer was offended and complained to one of the department stores. Within 20 days, a private group of painters hired by one of the stores was sent to make sure that the erection would be removed. However, the slogans ‘bless’ and ‘the best is yet to come’ remained unmarred.

Meanwhile, the police sent a report to the central district department saying that the graffiti ‘offended public morals’ and ordered public sector cleaners to remove it. However, due to a lack of state resources, it took eight months for them to come into action. The moment they did eventually get on top of the roof, they began to remove the vertical iron blinds that had already been partly cleaned eight months earlier by the privately hired painters.

The supervisor of the building called the police for the illegal invasion of the public cleaning crew and the illegal removal of private property, as had been neither requested nor licensed by the owner. The police arrived and arrested the cleaning contractor and one of his employees. A few days later this employee appeared on the state TV channel ET1, where he complained about his irrational arrest (Figure 8). In the same broadcast, journalists showed the graffiti and argued that ‘it is not possible for someone to make money from these paintings’, completely missing the point of why this intervention was carried out in the first place.

5 Years of Action – Interview

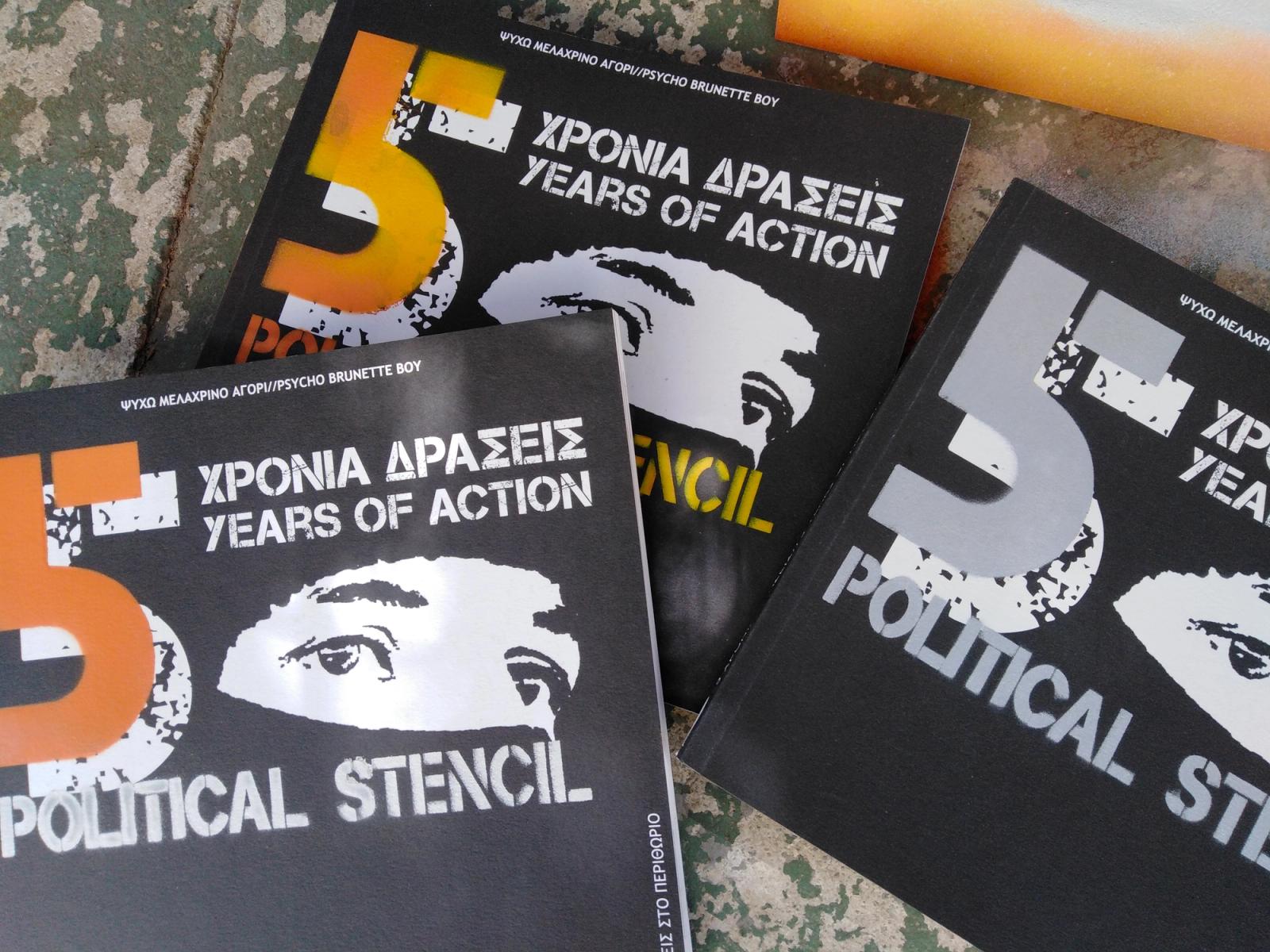

The Political Stencil Crew’s income comes from book sales, as well as donations and other contributions. Selling books provides the crew members with a basic income which allows them to move around, buy materials and paint, and cover other expenses. The team is self-financing, and has no contacts with foundations, sponsors, public authorities or companies.

Both their first book – published in 2014 and titled Political Stencil in the Streets of Athens – as well as their second book – which came out in 2019 and is called 5 Years of Action – have been self-published. Following this latest publication, which provides an overview of Political Stencil’s work of the past five years, Nuart Journal took the opportunity to talk to the crew.

Why did you decide to produce this book?

Because street art is temporary art, this means you can spray now, but by tomorrow it can disappear. So, we wanted to have a record of our actions. We have produced many hundreds of stencils and bombings over the last five years.

In the introduction to the book, you point out that all graffiti involves a kind of political action (when done without permission). In what sense is Political Stencil’s work political?

We use political stencils as a means to have an influence on society. We are a part of a bigger movement. We are working in the interest of the working class, the anarchists, the students, the unemployed – so we use our art to communicate demands from these parts of society.

Your work seems very responsive to the socio-political environment in Athens – do you think that the crisis has stimulated more people to engage in artistic expression on the streets?

Definitely. There has been an explosion of creativity since 2008. There are many groups and individuals going out to spray. We are in a constant crisis in Athens, because we have had so many things happen. In 2008, there were huge demos and rallies, and conflict with the cops. Then we had the economic crisis, and then a massive wave of refugees in 2015–2016. But when society has to resolve multiple problems, people’s creativity and involvement in art booms.

Does the Political Stencil Crew aim to activate people’s artistic and political agency? Do you think people are encouraged to go out and make their own art, after seeing your work?

Yes, this is our purpose – to inspire the people to action. You know, in Syria, the incident that triggered the civil war was someone spraying a wall. So, this is our aim. That doesn’t mean we achieve it, because we can’t know for sure the impact of our actions on others, but we do know that we have thousands of followers on social media, and we know that we are touching people’s hearts and minds. And very often we receive messages from people asking about techniques in stencil methods, and asking questions about how to paint in different places, and we send people advice and free programs. I think that we are effective somehow, in helping people to go out and spray themselves.

Figure 7. ‘The best is yet to come’. Political Stencil, Athens, Greece, 2017.

Figure 7. ‘The best is yet to come’. Political Stencil, Athens, Greece, 2017. Figure 8. A still from Greek national television (2017); the partly censored artwork by Political Stencil and the man who was tasked by the authorities to remove it, but got arrested for doing so.

Figure 8. A still from Greek national television (2017); the partly censored artwork by Political Stencil and the man who was tasked by the authorities to remove it, but got arrested for doing so.

In your book, you describe fascism as ‘the absence of humanity and compassion’ – your work covers an incredibly diverse range of political topics and human rights issues, including LGBT rights and homophobia; women’s rights and sexism; refugee rights and xenophobia; the impact of the crisis and austerity policies; the problems caused by drug dealing; art to enhance the lives of women with children in prison – and protests against particular politicians and so on. Why do you take on so many issues?

We have a diversity of unresolved problems in Greece, and so we produce art about the multiple problems we are faced with. We wouldn’t want to be just an anti-fascist crew – there are plenty of anti-fascist crews that already spray a lot. We wanted to make something wider, to embrace people from the many parts of society that are invisible, that need someone to spray for them – even if it’s a gay student pushed to suicide, even if it’s for members of society who are not politically engaged. Because everyone matters.

What’s next for the Political Stencil Crew?

We have a big mural on the way – illegal of course! The government is planning to make a huge celebration of 200 years of the Greek state, so we are planning to make a huge painting about this, mocking this bullshit. We are also planning a lot of small-scale actions – we are helping to raise funds to help a group of anti-fascist activists who got arrested by the cops. They have to pay €30,000 for their bail. We are going to help by selling books and giving money from our own funds. And we are helping a refugee squat that the government is planning to evacuate. There are many refugee squats in Athens. This refugee squat called us and asked us to do something with the kids from the squat – some stencils, and some spraying around the neighbourhood – and we hope that this will be a tool which will help them to avoid this police raid. So, we are very busy!

All photographs ©Political Stencil

Bampiniotis, G. (2004) Glossary for the Office and School. Athens: Lexicology.

Belle, J. (2007) The Mirror of the World. Athens: Metaixmio.

Halliday, M. (1985) An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Arnold.

Lawrence, T. E. (1927) Revolt in the Desert. London: Doubleday.

Marighella, C. (1985) The Guerrilla Warrior Handbook. Chapel Hill: Documentary Publications.