In the summer of 2019, the streets of Hong Kong became a global stage of a still-ongoing fight against authoritarianism. This was not the first time for the territory to find its otherwise carefully maintained and seemingly orderly public realm turn into a space for political mobilisation in response to increasingly diminishing freedoms. Yun-Chung Chen and Mirana M. Szeto (2017: 69-72) argue that this kind of resistance began with Occupy Queen’s Pier in 2007, when an attempt was made to stop the demolition of the Pier, which was a significant transport hub but also an important civic space. Since this Occupy movement of 2007, there have been several moments in which important spaces in Hong Kong were reclaimed through collective civil disobedience and with the intention to ‘speak in the face of power’ (Chen & Szeto 2017: 80). Indeed, as Chen and Szeto (2017: 81) assert, the reclamation of public space in Hong Kong ‘has been a means for political mobilization and building of civic and political subjectivity in a context of growing political repression’.

What is new to the movement of 2019 is the explosion of written notices of discontent in the spaces of the city. Don Mitchell (2003: 35) contended that it is not predetermined ‘publicness’ that makes a space public, but that it is a particular group in society that makes space public through either deliberate or unplanned actions. Hong Kong’s public spaces have become ‘contested terrains’ (Loukaitou-Sideris & Ehrenfeucht 2009: 30) through physical occupation, but citizens have also resisted the ‘disciplinary demands’ (Geyh 2009: 1) of the urban spaces in which they live through a visual occupation of the walls of these terrains. Rather, the public’s demands to have its voices heard have been made through a reclamation of what could be called a ‘contested urban canvas’. Hong Kong’s façades, windows, bus stops, underpasses, and any other of its wall-like surfaces have been occupied and repurposed as canvasses for ‘voicing out’ – something common in many parts of the world, but relatively uncommon in the context of Hong Kong until quite recently.

The walls of Hong Kong’s contested terrains were initially covered in coloured memos, followed by increasingly well-organised poster arrangements. Soon, however, more ‘permanent’ messaging emerged around the urban areas of the territory – Hong Kong’s sporadic graffiti writing quickly developed into rich spatio-textual discourses not only around the so-called Lennon Walls, but along the entire stretch of urban space where marches and gatherings were held. More specific locations in the city also invited painterly correspondences. Particularly, façades of government buildings, entrances of MTR stations, and shop fronts of businesses that are outspokenly pro-Beijing turned into critical canvasses of sorts. Hanauer (2011: 316) suggested that ‘the uncensored nature of graffiti writing (or to be more exact, the illegal nature of all graffiti writing) creates a situation in which competing political understandings can be presented’. In Hong Kong, this competition of opposing political ideas plays out not just between one graffiti text and another, but it eventuates in a visual power play that involves the erasing of these texts and their subsequent reappearance.

While the urban canvas is reclaimed in pursuit of freedom, constant attempts are made at a visual silencing of the voices on Hong Kong’s walls through different tactics. Urban façades are written on, yet are often quickly painted over, brushed out, or otherwise covered up. In this competition of voices and their erasure, the public space becomes an active space for discourse. With every attempt at concealing messages of revolt, the authorities and other institutions of power both produce obvious markers that uncover their intended ‘silencing’, and unintentionally encourage more graffiti precisely by creating new and quite perfect empty canvasses. Indeed, where coloured memos and posters were relatively easily (though never entirely) erased – leaving behind scraps of paper; remainders of discontent; visual proof of societal scarring – the attempts at erasing Hong Kong’s graffiti that ‘speaks in the face of power’ have led to a kind of political dialoguing between voices and silences. This is the contested canvas of Hong Kong: in a political context where the authorities have chosen not to listen but to suppress, urban walls become canvasses that not only present ‘competing political understandings’, but also record failing attempts at concealing discontent.

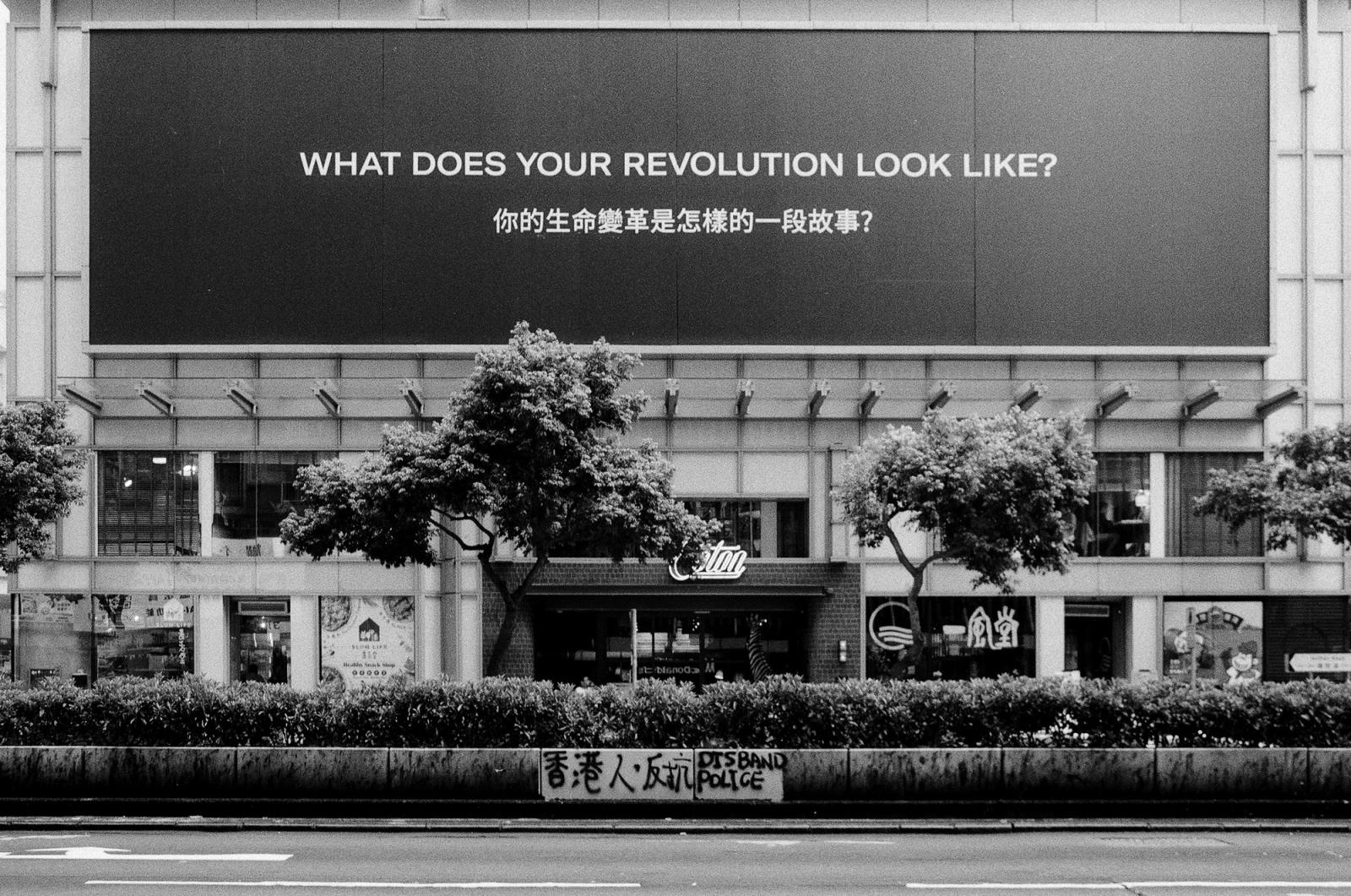

‘Hongkongers, rise up!’ and ‘Disband police’ written on a Jersey barrier, while hotel Eaton HK’s billboard features in the background. Graffiti can be found everywhere, especially around main roads where marches take place. Messages of protest have become part of daily life. Attempts are made to cover them up, but in a context where the authorities choose suppression over listening, freshly painted surfaces invite new messages to appear. Jordan, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Yu Wing Ching.

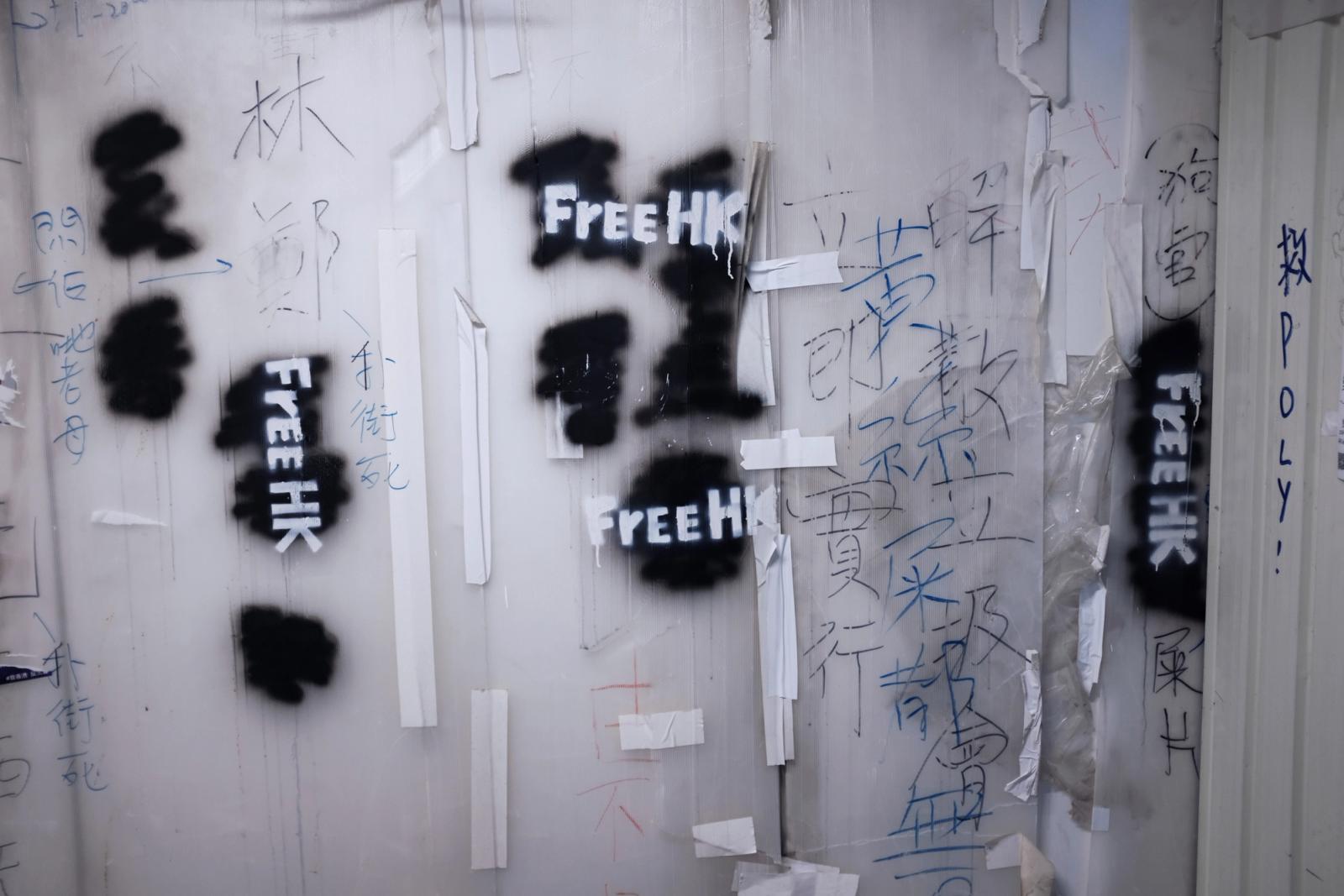

‘Communist bank’, ‘Say no to RMB’, ‘Liberate Hong Kong’, ‘Revolution of our time’, ‘Our leader is conscience’. Mainland Chinese banks use white construction hoarding to cover their damaged shop fronts, providing ample space for graffiti. Prince Edward, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Yu Wing Ching.

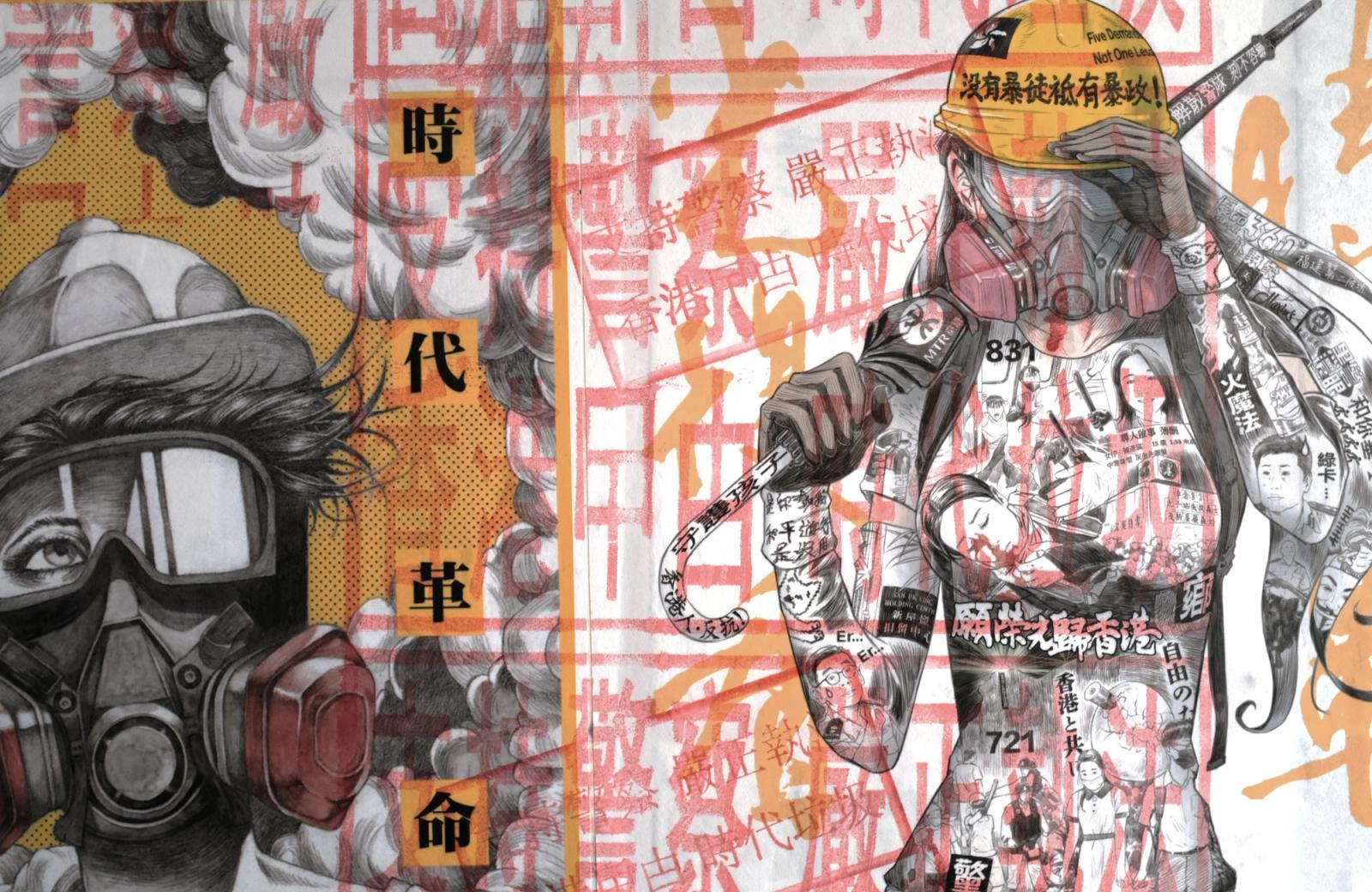

Around Hong Kong’s contested Lennon Walls, posters are not only ripped off, they are also responded to in other ways. Competing political understandings emerge in a collage-like, mixed-media fashion, with red-inked chops being a typical medium for supporters of the establishment: ‘Help the police enforce the law. Hong Kong cockroaches [protesters] are the trash of our time.’ Tuen Mun, New Territories, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Anneke Coppoolse.

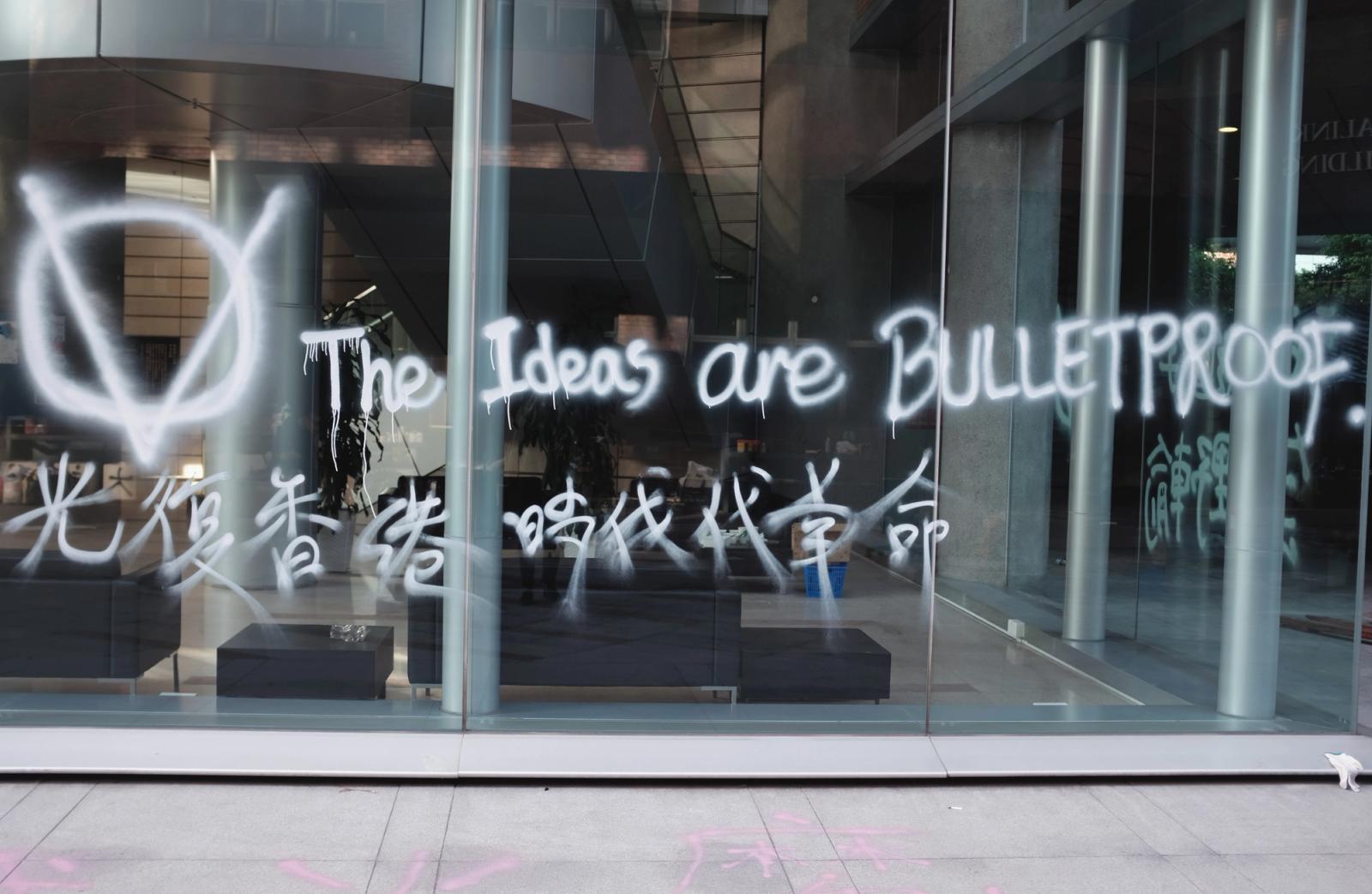

‘Liberate Hong Kong, revolution of our time’ and ‘The ideas are bulletproof’, featuring beside the V for Vendetta symbol. Several university campuses had become sites of unimaginable conflict. These are the windows of one of the administration buildings. The message is loud and clear. Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Anneke Coppoolse.

Hong Kong has been a commercial space from its outset; a neoliberal spectacle with billboards and other visual stimuli that suggest economic activity and prosperity. Its billboards have been overridden. Displays of commerciality have transformed into displays of discontent: ‘Five demands’, ‘Heaven will destroy the CCP’, and ‘Liberate the Hong Kong Polytechnic University’. Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Anneke Coppoolse.

Billboards at tram stops have been taken down and replaced with white boards; an open invitation to graffiti, which gets erased by the authorities not long after it appears. A competition of opposing political understandings results in painterly abstraction. Central, Hong Kong Island, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Chan Ka Man.

Perfect canvasses are created unintentionally, ‘covering up’ damaged walls and inviting fresh graffiti writing at the next protest or sooner. Central, Hong Kong Island, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Chan Ka Man.

The covering up of façades sometimes serves also another purpose; contributing to the creation of presumed ‘normalcy’. A great number of station entrances have been turned into ironclad fortresses by MTR, a corporation that is known to collaborate with the authorities. Soon enough, plaster and paint will be added to this entrance to make it look ordinary. Until fresh graffiti emerges. Central, Hong Kong Island, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Chan Ka Man.

The act of ‘covering up’. The windows of MTR entrances have been covered up with iron plates, plaster, and fresh paint. Jordan, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Anneke Coppoolse.

No matter the effort individuals put in repainting MTR entrances, the public’s voice persists: ‘Rapist’, ‘Murderer’, ‘They [police officers] don’t need a reason to pepper spray you’. Yau Ma Tei, Kowloon, Hong Kong, 2019. Photograph ©Anneke Coppoolse.

Anneke Coppoolse is an Assistant Professor in the School of Design of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (PolyU Design). Her research is located at the crossroads of design and cultural studies and specifically focuses on the visuality and materiality of urban everyday life.

Chan Ka Man is a communication designer and a student at PolyU Design. She has a research interest in the locat-ions of communication design in the context of culture and local politics –specifically as it organically appears and disappears in streets and on walls.

Yu Wing Ching is a visual designer and will soon graduate from PolyU Design. She mainly works with photographic images and related printing techniques. She has an interest in the relationship between images and individual and shared experiences of social crisis.

- 1

In 2014, during an earlier democracy movement that is generally referred to as the Umbrella Movement, a number of central roads in Hong Kong were occupied for months. At the main site, near Hong Kong’s Central Government Complex, the wall of an outdoor staircase was covered with messages of support and political grievance, written on coloured memos. The wall came to be referred to as the Lennon Wall, named after the original Lennon Wall in Prague, Czech Republic. During the still-ongoing democracy movement that erupted in the summer of 2019, similar Lennon Walls popped up around (and outside of) Hong Kong – in underpasses, on footbridges, and in other strategic locations with much pedestrian traffic. These Lennon Walls were initially covered with memos, but soon a nearly continuous production and distribution of posters that responded to the most recent events in the movement helped convert these otherwise unremarkable spaces of pedestrian passage into sites for conversation. These sites, however, also became places of conflict. Especially those located in areas where larger concentrations of opponents of the movement reside, would see posters getting ripped off and arguments break out between people with opposing views.

- 2

The Mass Transit Railway (MTR) is the main public transport network serving Hong Kong.

- 3

Interesting to note is that the erasing of messages of discontent from the Lennon Walls turned into a more organised form of political participation among supporters of the government when controversial lawmaker Junius Ho launched a clean-up campaign, calling for volunteers to participate in a clearance action on 21 September 2019. This was, in turn, an invitation to supporters of the movement to expand the Lennon Walls and produce fresh batches of posters.

- 4

RMB is the abbreviation for the renminbi, the currency of the People's Republic of China. Hong Kong has its own currency: the Hong Kong dollar.

- 5

Hong Kong’s protests began when its pro-Beijing government proposed the ‘Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill 2019’, which would allow extraditions between Hong Kong and territories Hong Kong currently does not have extradition agreements with, among which Taiwan and Mainland China. The bill was perceived as a threat to Hong Kong people’s (and visitors’) freedoms as it could subject them to the legal system of the Mainland. Moreover, while the Hong Kong government claimed that the proposed amendment responded to a murder case in Taiwan with a suspect in Hong Kong, Taiwan’s Mainland Affairs Council that deals with cross-strait matters had indicated not to have an interest in the extradition of the suspect and also other foreign government bodies had expressed concern about the bill. When the Hong Kong Government and Chief Executive Carrie Lam initially continued to defend the extradition bill, the protests developed into a bigger movement with five core demands: full withdrawal of the proposed extradition bill (which was withdrawn after many weeks of protests and therefore ‘too little, too late’ according to the protesters); the establishment of an independent commission of enquiry into alleged police brutality; the retraction of the characterisation of the June 12 protest as ‘riots’, as those charged with ‘rioting’ can face a prison sentence of up to ten years; amnesty for arrested protesters and, lastly, the implementation of universal suffrage for the elections of Hong Kong’s Chief Executive and the Legislative Council.

- 6

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), also called the Communist Party of China (CPC), is the ruling political party of China.

Chen, Y.C. & Szeto M.M. (2017) ‘Reclaiming Public Space Movement in Hong Kong: From Occupy Queen’s Pier to the Umbrella Movement’ in: Hou, J. & Knierbein, S. (eds.) City Unsilenced: Urban Resistance and Public Space in the Age of Shrinking Democracy. New York: Routledge: 69-81.

Geyh, P. (2009) Cities, Citizens, and Technology: Urban Life and Postmodernity. New York: Routledge.

Hanauer, D. (2011) ‘The Discursive Construction of the Separation Wall at Abu Dis: Graffiti as Political Discourse’. Journal of Language and Politics, 10(3): 301-321.

Loukaitou-Sideris, A. & Ehrenfeucht R. (2009) Sidewalks: Conflict and Negotiation over Public Space. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Mitchell, D. (2003) The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. New York: The Guilford Press.