For the last five years, I’ve been thinking about the impact that Instagram has had on graffiti and street art. I grew up in the graffiti scene in the 1980s and ‘90s. We had no technology in the way that we do today. No mobile phones, no internet. So, like many of us, I’ve lived through a transition where art forms like graffiti, and later street art – which emerged on the cusp of the digital revolution – have now shifted into a space where we are drenched in forms of media culture.

This is not a pro-Instagram talk, but as a scholar and as someone who makes art on the streets, I’ve become fascinated with how Instagram has reorganised aspects of street art culture and also how it has made visible some things that were previously invisible. My new book, Instafame, looks at the top 100 accounts for street art and graffiti. It gives a broader theoretical concept to this digital shift and it looks in detail at the kind of data that is produced by Instagram.

This project began with the very simple realisation that, when we are flicking through Instagram on our phones, there is a vertical feed – a mesmerising transition of images –, our finger is rubbing the screen and the images are floating up and down. For me, the transition of images across our eyes has a lot of similarities with the experience of being on a train, looking out the window. There’s a longstanding theoretical tradition that thinks about the connections between train travel and the emergence of visual technologies like cinema, but for me it was an intuitive realisation that scrolling through Instagram is like looking at graffiti from a train.

A Melbourne train carriage, with windows resembling the square format of the early Instagram feed.

A Melbourne train carriage, with windows resembling the square format of the early Instagram feed.

A spectator photographs a mural by Rone. Melbourne, Australia, 2015.

A spectator photographs a mural by Rone. Melbourne, Australia, 2015.As someone who looks at graffiti, you begin to develop particular techniques of scanning images. Graffiti itself is very much attuned to the logic of Instagram, because graffiti is all about grasping your attention in an instant. Something about this very small fraction of time – the instant, the speed of contemporary culture – gives graffiti a real opportunity, a real connection, to the perceptual apparatus that has developed on Instagram. My point of argument in the book is that Instagram accelerates and amplifies forms of street art and graffiti. In more formal terms, it institutes a series of feedback loops that influence every aspect of the production and consumption of graffiti. I’m thinking here about that moment when graffiti writers and street artists begin to embrace technology and start to use their phones in the street, there’s no more sketches, no more blackbooks – suddenly this digital object becomes the filter through which art is produced. Phones also become integral to the documentation of art on the streets, and they become the tool through which we all begin to encounter street art. There has been a radical amplification – where street art is now available to enormous audiences who will never encounter the work in its original location. Digital audiences start to swell, and now dramatically outnumber the people who would ever see the work in the flesh.

And there is also pressure on artists to become involved in this series of transactions that revolve around Instagram. You know from your own use of phones that Instagram produces certain types of anxiety, certain fears about visibility – and it’s not too long before we see artists being drawn into that system – feeling like they have to be on Instagram, as this is the place where things are happening.

So, we have a series of feedback loops that really begin to organise the field of street art in interesting ways. They make visible new forms of aesthetics, which are a correlate of the ‘likes’ on Instagram; they also begin to organise forms of affiliation, this is the idea of followers; and finally, there’s this notion of attention (or comments). Indeed, the attention economy is organised by the architecture of Instagram. We begin to see in Instagram a collapsing of context, and a radical equivalency between categories which were previously separate. We begin to see forms of collapse, both in terms of spatial categories and in terms of temporal categories. To take one example, here’s a couple of images: A crate man figure in Melbourne in 2005 and a work by Ben Wilson on the Millennium Bridge in London. The work on the left, as you can see, is made of milk crates, and the work on the right is the size of your fingernail.

A ‘Crateman’ (sic) at Victoria Park station, Melbourne, mid-2000s and a painting on discarded chewing gum by Ben Wilson, Millennium Bridge, London, 2015.

A ‘Crateman’ (sic) at Victoria Park station, Melbourne, mid-2000s and a painting on discarded chewing gum by Ben Wilson, Millennium Bridge, London, 2015.

So, in terms of spatial and temporal collapses, when these works are posted on Instagram they are often out of sequence – the spatial scale of the two works is completely missing, the spatial context in which they happen evaporates, and any sense of the duration of the works is lost. These crate men figures existed for only a month, while Ben Wilson’s work is virtually indestructible, and will last at least ten years. In the world of Instagram, we have this radical equivalency where space and time start to collapse. We can see this in many different types of production. We see artists playing with, or being sucked into, this radical equivalency, as people try to respond to the force of gravity of Instagram.

This all shows a number of very negative effects; the erosion of experience, of tradition, and of many of the earlier forms of graffiti. The title of my book – Instafame – is therefore an idea that’s filled with cynicism. This idea that the goal should be fame, and that you can gain this instantly. But as a scholar, I began to think about other aspects of Instagram and thinking about how it begins to make visible a number of things that scholars have been interested in, but have been unable to fully grasp or fully represent. So, in the second part of this talk I want to show some examples of what I have done recently by extracting forms of data from Instagram and using that to represent aspects of street art.

I’m trying to avoid the impression here of giving a Ted talk and also trying to avoid the impression of giving a share market report. My slides look a little bit like a share market report of street art, but really it’s about taking some tools and inventing some new methods that will help us to chart the institutionalisation of street art. So, for instance, some of my work has been about addressing this question of gender and thinking about how we can use Instagram to produce statistics to show the limited representation of women in the industry elite. As someone who got acquainted with street art at a time when it was a radical democratic practice, a practice that was an open invitation to change the city, it’s almost with horror that I lived through this technological change, but also this institutional change, which is producing a kind of aristocracy within street art – often with artists whose work I really admired, but I just had this uneasiness about this. So, I’m hoping that this work will not add to this production of an aristocracy, but rather provide more visibility to some of these tendencies.

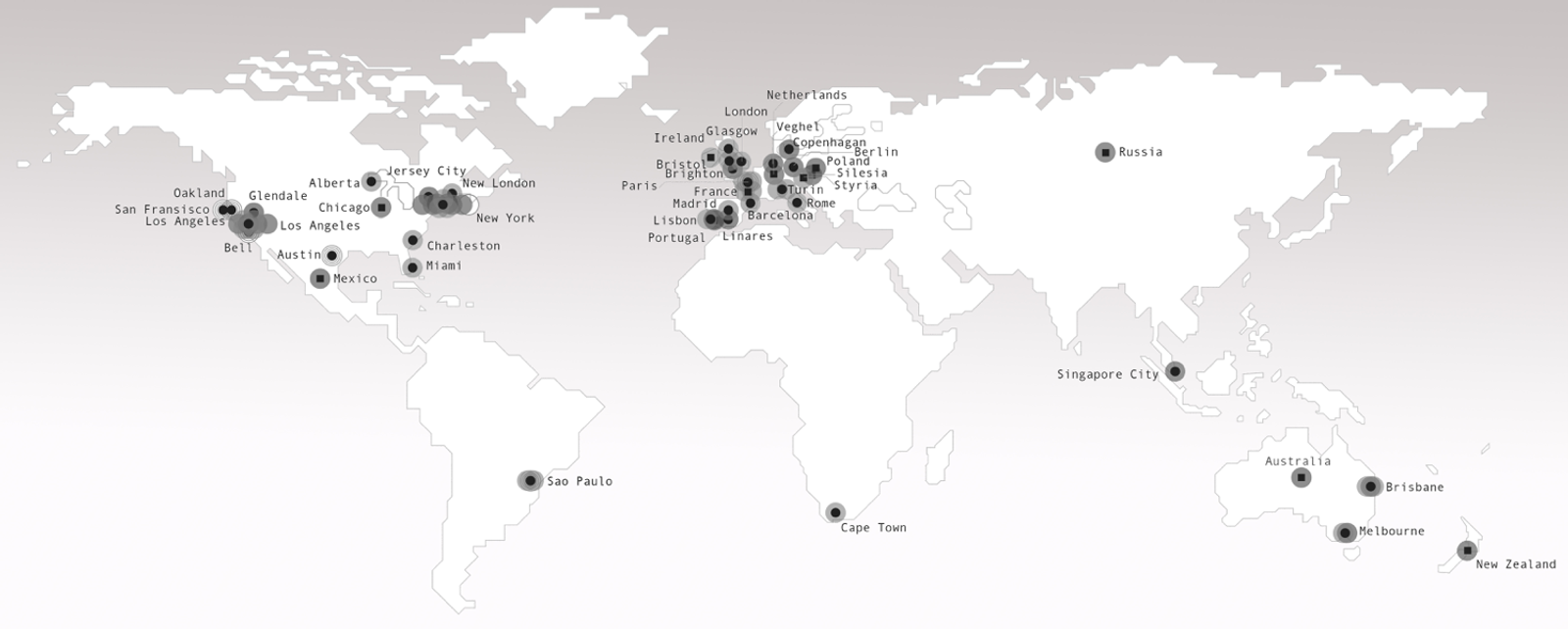

I’ve been developing data on the 100 most followed Instagram accounts for graffiti and street art, and I’ve used this data in many ways to try and visualise this global trend, particularly over the last four years. So, this is just one example; thinking about street art – which is framed as this global practice with our coffee table books full of images in exotic locations – we can see from this mapping that the elite in street art really are clustered in three zones: on the West Coast of the United States, in New York, and in Western Europe. So, while street art has shaped the globe in many different spaces, these metropolitan centres in the United States and Europe are still the focus of this kind of work.

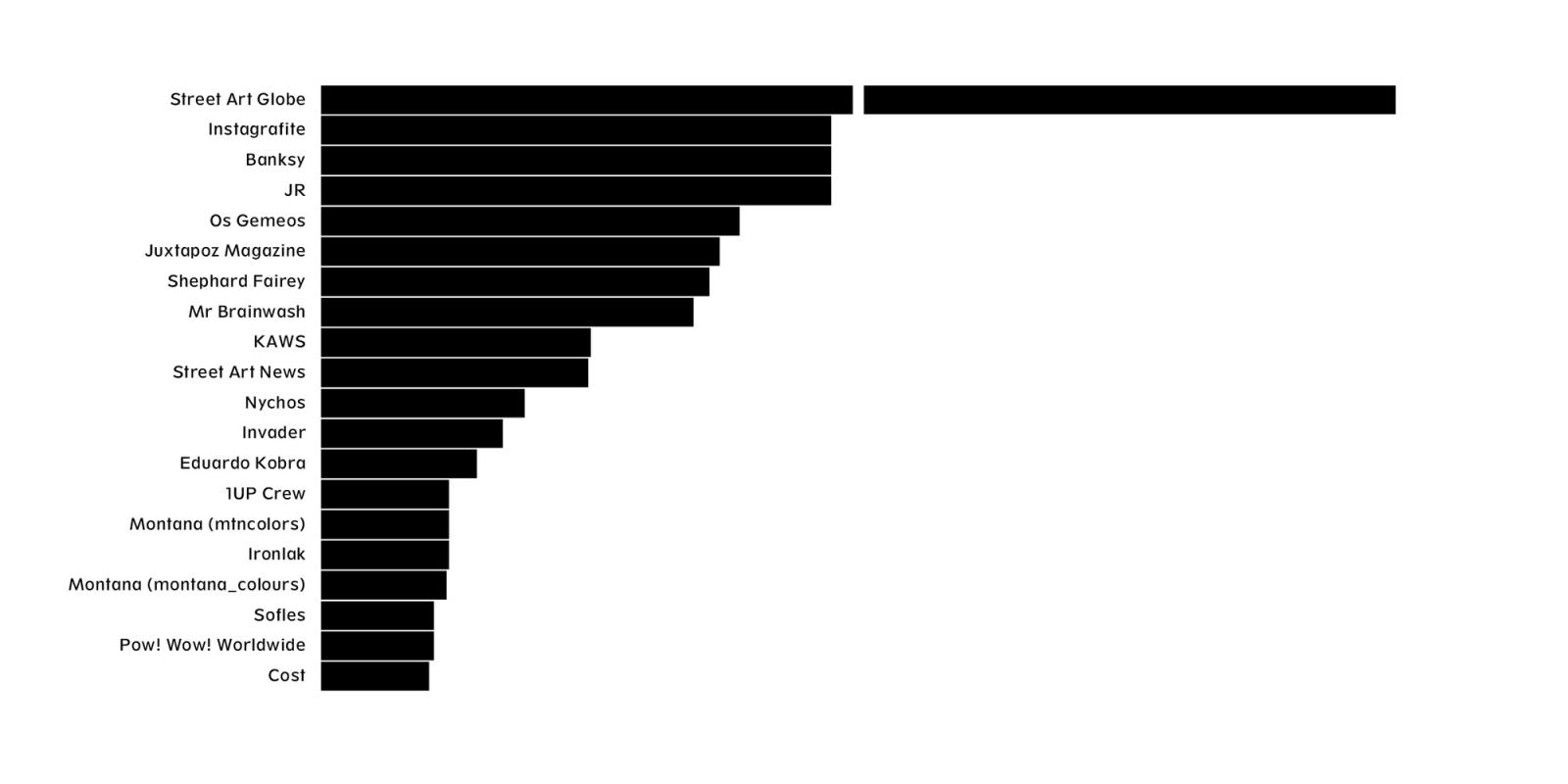

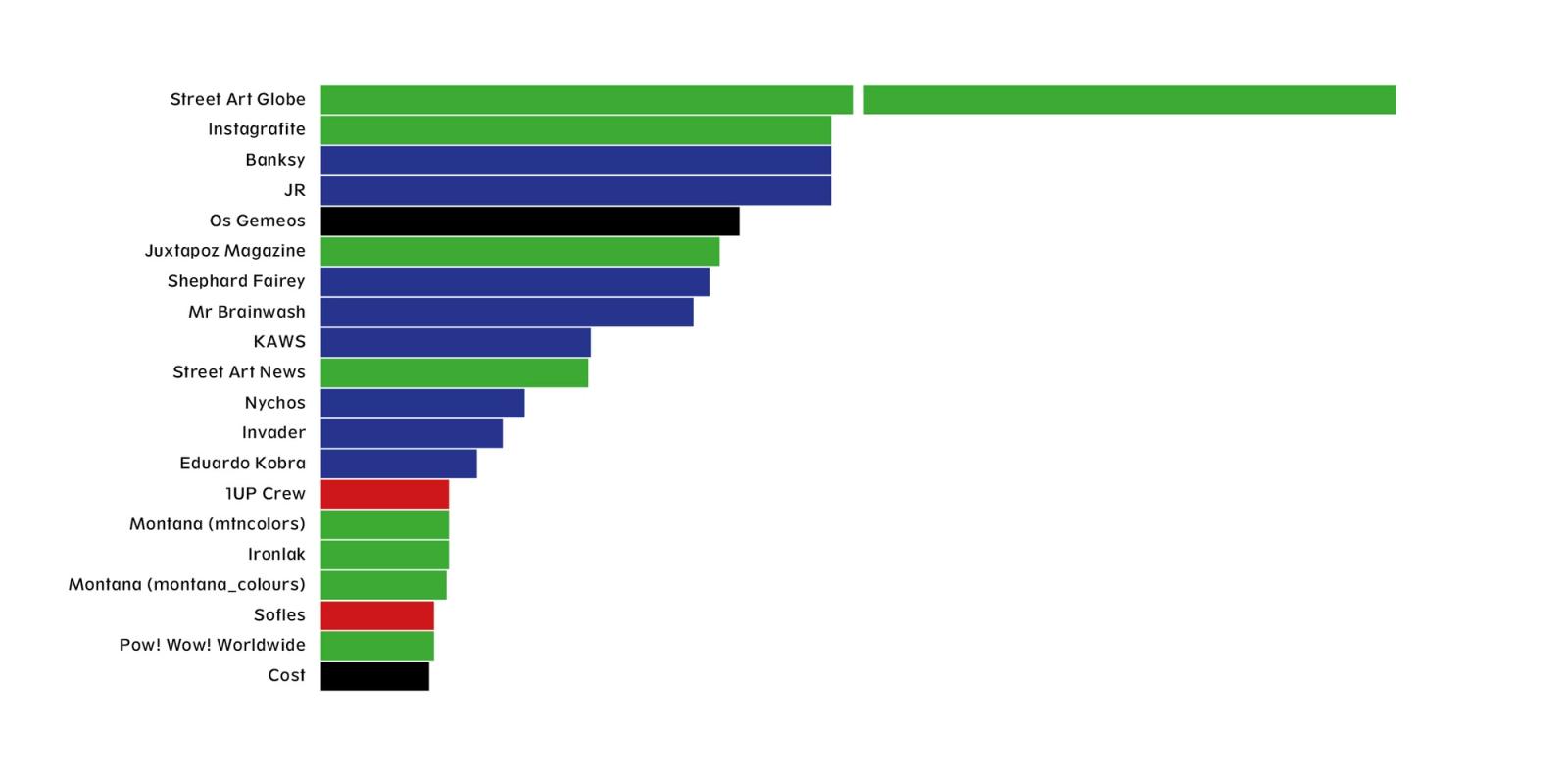

And here’s a mapping of the most followed accounts, the top 20 accounts on Instagram:

These are the elites of street art; the artists, festivals, organisations, and publications that have the most followers, and therefore the most influence. Once we have data like this, other kinds of questions emerge. And one of the ways that I wanted to think about this space is in relation to graffiti and street art, and the relationship between these two formations. In many cities around the world, this has become a topic of debate over recent years – often a topic of contestation, conflict, and even physical conflict. Having an affiliation to both graffiti and street art myself, I never see this conflict in black and white. It’s not that I don’t think that the two formations have differences, it’s mostly that I actually see they also have many similarities, which set me thinking about how I might code this data. Whereas ideas and concepts related to graffiti are represented by the red in the image below, those related to street art are in the blue, while the overlapping space in the middle is represented by the colour purple.

When we look at the artists in the top 100 you can see that they have very varied backgrounds, but on many occasions, there is often a very strong relation between graffiti and street art. Either the artists have had a strong origin in graffiti and then have moved into street art, or perhaps they have a parallel practice, like Banksy was rumoured to have a parallel practice of street art and more illicit graffiti, or perhaps they had a hybrid kind of notion. So, trying to think about this data, what does it look like if we begin to code it in relation to these categories? This is obviously a highly controversial exercise. It’s very difficult, for example, to think of a way to categorise the artist duo Os Gêmeos, as these two artists have grown up with hip hop, but now produce very much ‘street art’ kind of work. That’s why for me they exist in this hybrid (purple) sort of space.

In each particular case, I’ve weighed up the artists’ allegiances to graffiti and street art in terms of their background but ultimately, I’ve simplified the data and given their Instagram accounts a kind of coding. All the green accounts in the image below are institutional accounts – they are not artists’ accounts, they are either aggregated displays of street art, or they belong to publications like Juxtapoz. You can see that the top of this tree of the elite is dominated by street art accounts, there are very few pure graffiti writers in this top 20 of most followed accounts. This changes as the data moves down. But thinking about how this might help us to address some of these debates really shows some of the complexity of this space.

So, the title of my talk is ‘Snitches, Glitches, and Untold Riches’. There’s a saying in graffiti culture – a very clichéd saying – about ‘snitches get stitches’, meaning people who cheat other people and talk to people they shouldn’t, will get physical abuse – but I’m not really into that! I wanted to update ‘snitches get stitches’ to think more about glitches and also riches, because these are two elements that are really now very visible on Instagram. So, we have snitches (or bad behaviour), glitches (which is the way in which the architecture of Instagram itself shapes some of these ideas), and also untold riches (that is, the economic and social affiliations and arrangements that underpin what is now a big industry, which is very valuable and lucrative for some).

Let’s have a look at some snitching and glitching. I’m going to be the snitch in this and I’m going to call out the biggest account on the list. I’ve been tracking this data by hand for the last four or five years, and I want to tell you about just one element, one story, about the transition behind an account like Street Art Globe, which is now not just the biggest account in the top 20 list, but the biggest account by far.

It has 7.2 million followers and though it is called Street Art Globe, it’s not just about street art, it’s got weird pictures and videos of different kinds of art. It’s a really voracious monster that’s gaming the system to produce very high scores and drag in new followers and I want to talk about a little controversy that emerged around Street Art Globe. This is important because it raises some broader questions about the organisation of Instagram. In January 2017, there was an attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris, a very shocking incident that drew a lot of attention around the world, including a lot of attention from street artists. In the hours after that attack, an drawing of pencils – one whole (yesterday), one broken (today), and a third, where the broken pieces are sharpened into new pencils (tomorrow) – was posted on an Instagram account with the name @Banksy. As we know, Banksy has a complex relationship to technology, and to social media; he does not like to be on a lot of social media. But there’d been this Banksy social media account weirdly floating around, not getting a lot of attention until suddenly, the eyes of the world were on this account. A lot of newspapers started to report that Banksy had a new artwork made in response to the Charlie Hebdo attack. But very quickly, those same newspapers had to adjust their reporting, as the day after it became clear that this was not Banksy’s account and this was not Banksy’s artwork. It was the artwork of a French illustrator, Lucille Clerc.

Because I had been following the data on these accounts, I was able to produce a different kind of narrative about what happened here. In my raw data sheet the names of the accounts on Instagram are coupled with a long number, which is the user ID. It turned out that the user ID of Street Art Globe is identical to the ID of the Banksy account. So, this shows that this was not Banksy’s account; it was an account which was very cynically run under Banksy’s name to gain more followers, posting images of other artist’s work, even work that was made in response to a brutal terrorist attack. And then, when it was uncovered, the administrators very quickly changed the name of their account to Street Art Globe. Their everyday practice of reproducing artists’ work without credit is cynical, but this was suddenly uncovered and became a lot more visible as a result of the newspaper reporting about the terrorist attack, so the artists had to be credited after all.

This is part of the inglorious history of Street Art Globe, its voracious interest in attracting followers, without any kind of traditional ethical arrangements in terms of moral rights of artists, or any sense of what’s going on in the world outside. It’s a beneficiary of this outrage economy. It has also forced artists like Banksy to start using their Instagram account. Banksy now has a verified Instagram account, with a blue tick. He wants to ensure that his name is not used to generate profits for this nameless personal corporation, but Street Art Globe has continued to simply refine its practices such that it continues to grow and draw in followers simply by bottom feeding off other artists’ work and intervening in this attention economy. So, I’m snitching on Street Art Globe!

What about some glitches? Here is a glitch that I found in the system. By glitch I mean a way in which the Instagram platform is not just a container for street art or a big electronic photo album, but actually a form of architecture that structures, produces, and processes the data and the images that are uploaded. To take one example, muralist SAINER has got a peak following on Instagram. He started with Instagram in 2013, posting images of very beautiful work that attracted a lot of interest and followers. SAINER has a close colleague he paints with called BEZT, whose work actually starkly resembles his own. BEZT joined Instagram a year later, in 2014. When you join Instagram, it’s like the snakes and ladders game where you start at the bottom of the tree, in other words, you start with zero followers. So, in analytical terms, this was an interesting contrast as BEZT arrived late to this technology, yet posting very similar kinds of work to SAINER as they have the same colour palette and realist style. In case they collaborated, they even posted images of the same works.

Screenshots of @sainer_etam and @bezt_etam accounts on Instagram.

Screenshots of @sainer_etam and @bezt_etam accounts on Instagram.

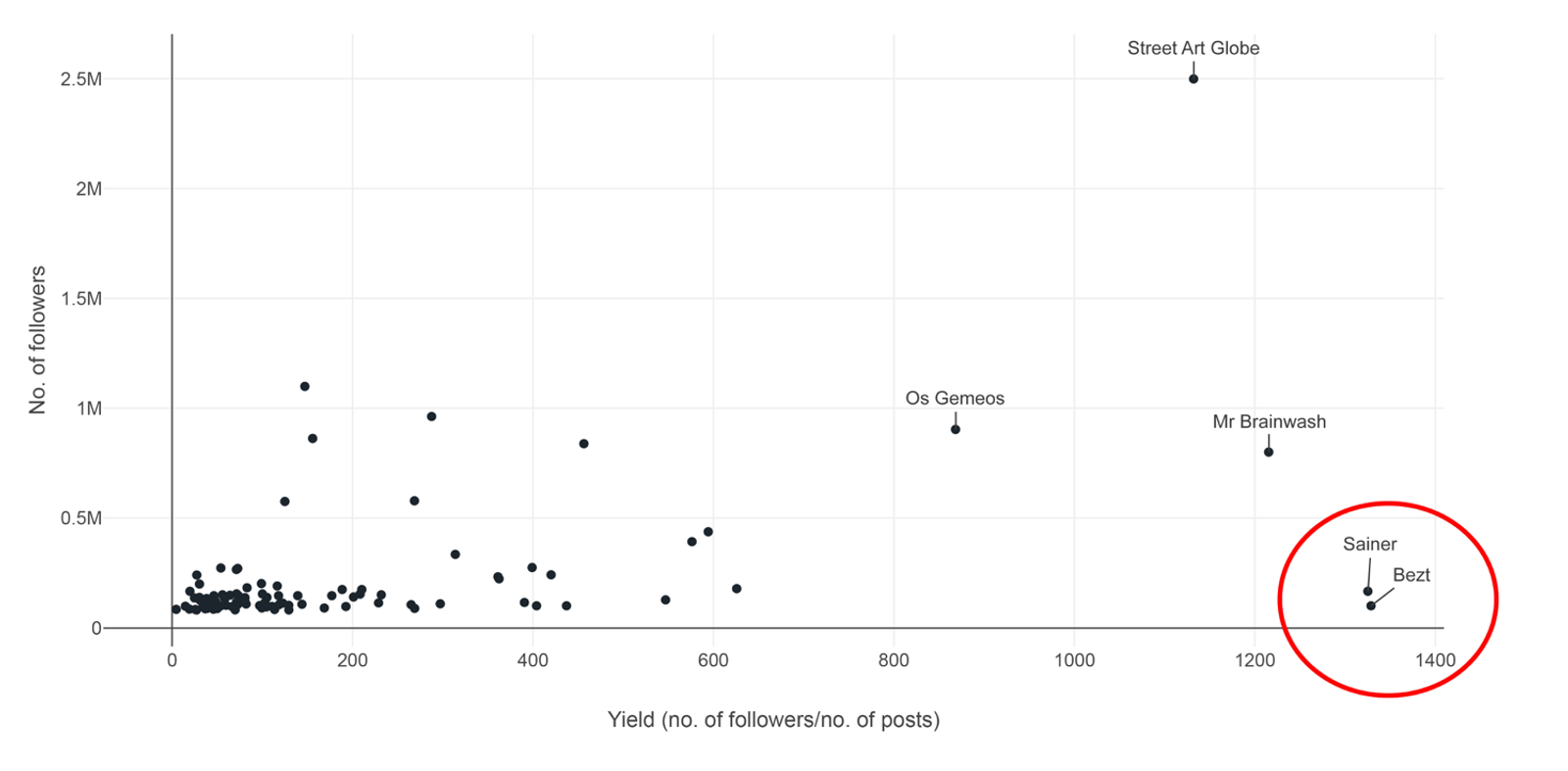

So, what happens to the data around these two accounts? What happens is a glitch in the system, which I will come back to in a moment. My question was, in terms of artists posting on Instagram, ‘which artists generate the most attention with the least number of posts?’ While some accounts post a lot of stuff to generate a lot of followers, other accounts post very little and yet still seem to generate a lot of attention. I invented a methodological category, which I call the yield of a post; the average number of followers that you would gain by posting something on Instagram. This yield will vary pretty widely for different accounts.

For those not used to looking at data, all the dots on the left hand side in the image above represent a kind of ‘normality’. This is the middle of the cluster – this is what happens to the accounts of most people when they post images, generating two, or four, or six hundred new followers for each image that they post. But there are also people who are real outliers in the system; Street Art Globe, situated in the top right hand corner, is posting a lot, but it’s also generating a lot of followers. Down at the bottom right corner we find SAIDER and BEZT, the crewmates making similar looking work, who joined Instagram at different times and as a result have different numbers of followers. And yet, the yields on their posts seem to be strikingly similar. That’s the glitch in the system that I find remarkable. These guys are the ‘Os Gêmeos of data’, they are data twins of each other. They don’t have the same amount of followers – SAINER has 210,000, BEZT only 131,000 – and yet the proportion between the number of posts they make, and the number of followers that they gain for each post, is very similar. So, there is something here about a hidden digital footprint, an unconscious patterning of audiences, that is slowly being made visible through some of this data.

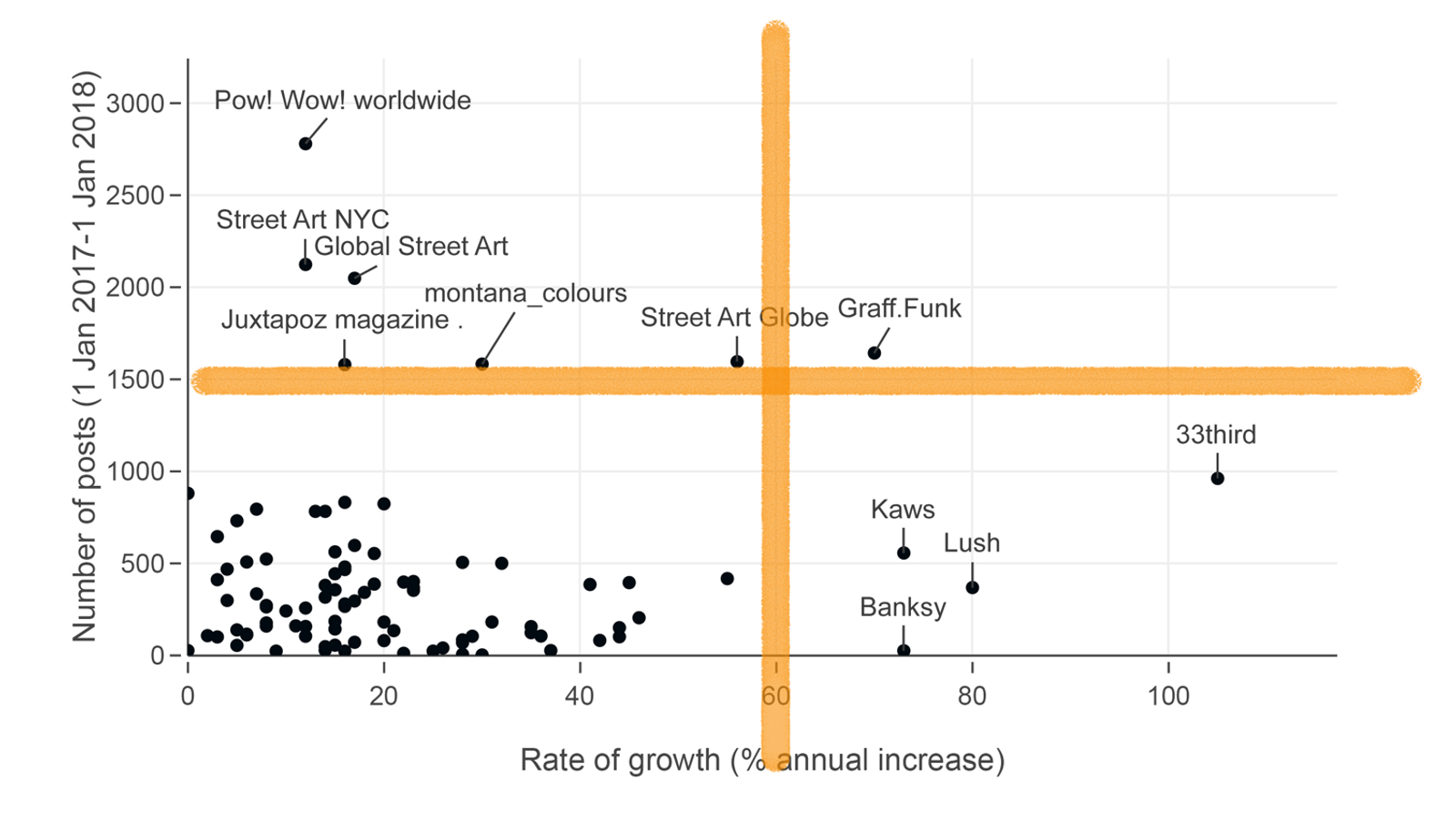

Let me give you one more example – thinking about untold riches. Here are some more dots on a page. Instagram is a regressive platform. That is, it is regressive like taxes can be regressive. It’s regressive because it rewards people who already have a lot of followers. Capitalism rewards people who already have a lot of capital, allowing them to make more capital. Instagram regressively rewards people who already have a lot of followers. So simply charting the number of followers in different accounts on Instagram isn’t necessarily going to be a very good model for anything. It tells you a lot more about when people came to the technology. What might be a better measure is thinking about this data over time. However, Instagram doesn’t allow you to do that. You can’t go on your Instagram feed and find out what number of followers someone had a week or a month ago, so it’s only through playing with this data for the last few years that I’ve managed to generate these kinds of patterns.

This is one of my representations of the world of street art and it uses the notion of rates of growth to generate quadrants. That is, four groups within the world of street art.

The first group, in the bottom left hand corner, is simply ‘most people’. These are people who post fairly regularly (up to 1000 posts in a year) and the rate of growth for these accounts is pretty strong, up to 40%. This is how most accounts evolve, but more interesting things happen in the other quadrants, most notably the top left quadrant. Here we have the accounts of those that are posting a lot more than the average person, and use Instagram really as a kind of broadcast medium; festivals, magazines, spray paint manufacturers and aggregated accounts like the one from Lois Stavsky’s Street Art NYC, who I like to single out, as she has posted 30,000 images on Instagram and posted three times more than the next most frequent poster in the period examined.

And then we come to the third quadrant in the bottom right hand corner. Again, an interesting cluster of data. Not so much in terms of where individual accounts are, but when we think about the rates of growth – if this was a share market, if you were thinking about what shares to buy, what’s hot right now, what are the accounts that are likely to grow really quickly – it’s in this little cluster of artists’ accounts. The accounts of three artists – Banksy, Kaws, and the Australian artist Lush (aka Lushsux) – are generating enormous growth, and we can attribute that to a whole range of reasons over a year, not just the number of works that they’ve made, but also the kinds of works as well as the kind of audiences that they are eliciting. Kaws has had a whole host of big gallery shows and other reasons why his Instagram account might be hot, Banksy’s account is always hot, and Lush’s work is often tailored specifically to the contours of Instagram, making arts data memes.

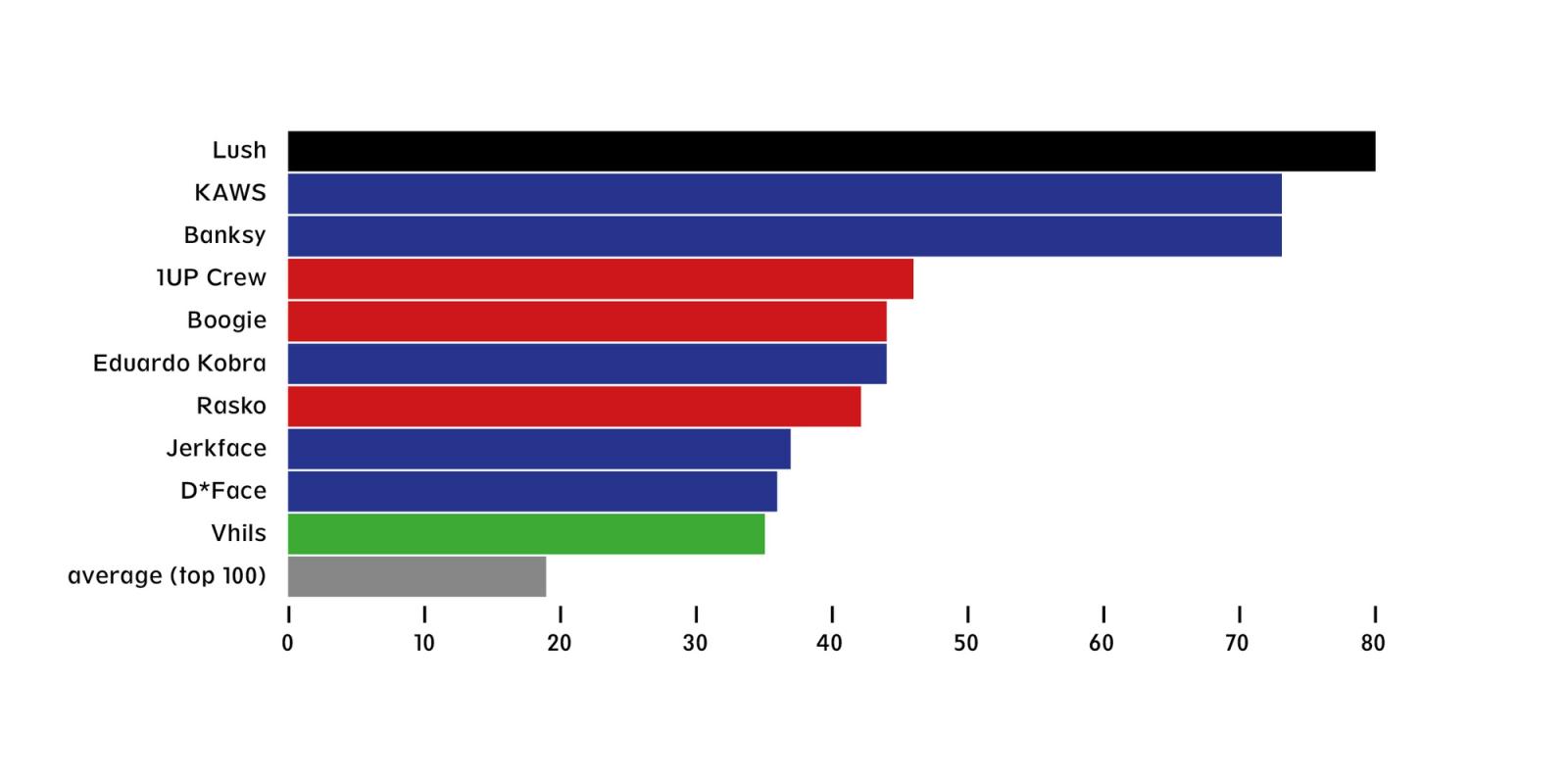

Finally, the image below shows the rates by which the accounts of the top 100 artists have grown over the last year. It’s another way of visualising the global institutionalisation of street art, but this time without thinking about how the architecture of Instagram is shaping the categories. Lush is on top of the list as a result of his explicit working of the Instagram platform, but other artists on this list make very interesting work too.

Although we should be critical of these analyses and think about how limiting they are, this project has been the first to chart some of these global relationships in graffiti and street art. I used 23,300,000 pieces of data to produce some of these maps, a very large number of global decisions which could help us chart some of these broader arrangements of taste, and think about how others are responding to this world – a once analogue world with neither smartphones nor the internet, but one that has long moved into a new digital paradigm.

Audience Questions

Street Art Globe is an account that started following the street art movement, but they have become a bucket of memes, jokes, and videos. I don’t think this is actually destroying street art, but the perception that street art is about something so stupid makes me angry. Is Street Art Globe so popular because it’s basically a ‘show’? In your opinion, why does it attract so many people?

MacDowall: I would say a couple of things. Firstly, there has always been ‘street art.’ There have been a lot of practices in the streets, and historically the term street art has been taken up in many different ways. In the 1970s, street art in the United States is Afro-American art, in other places like Italy, it’s about street theatre. So, leaving aside what it actually means, just thinking about the popularity of the term, it becomes a very important rhetorical container, and a very popular idea, in the early 2000s. Part of the attraction of an account like Street Art Globe is the idea of ‘street art’ in the title. This provides a space for very many different practices. So, the invention of street art is partly about the invention and promotion of a kind of ‘hashtag street art’. And what that does is open up a space that’s potentially infinite, and feels very democratic – streets are everywhere, artists are everyone, and we’ve created X and Y axes of practices that could include a whole range of things.

So, we could say that’s the more democratic answer – that people go to Street Art Globe because they are attracted to this very ephemeral notion of street art, that for them feels very open. But Street Art Globe is like a machine, like an algorithm. Maybe there’s no personal corporation behind it, maybe it’s just a churn of images. What’s clear is that they are watching very carefully to see which of the things that they post are responded to, when they are responded to, and by whom. I am not sure if you are aware of what it looks like to be an account holder with millions of followers. I spoke to a few people that had more than 100,000 followers, and I said to them, ‘have you imagined your audience?’ And they looked at me like, ‘Imagined? We don’t have to imagine.’ And they showed me their Instagram account. It’s not like our Instagram accounts. There’s a special Instagram account for people of that size. And they have an enormous amount of data about the countries and gender of their followers, about the time these people spend on their accounts, etc. This is computational capitalism; very carefully curated content designed like a shark to go through the ocean and eat as much attention as possible.

Is it a coincidence that most of these accounts are near the equator, and that all of the painters are white men – does this reproduce hegemonic power?

It’s no coincidence at all. In fact, in a geographical mapping exercise, I have data to show where artists were born, and where they are now based, in that top 100. And it’s a vortex that is pulling people from the South up to the North to those big metropolises. People are being drawn into that system. Instagram is about the reproduction, in this data set particularly, of hegemonic tastes. So, I want to be careful to map, but not to reproduce, this notion of the elite. I want to show how this elite world is operating.

All images ©Lachlan MacDowall.

Working across art-making and academia over three decades, Lachlan MacDowall is a scholar of graffiti, street art, and digital culture, best known for pioneering research methods that mix genres, images, and data. He has published widely on the history and aesthetics of graffiti, as well as urban informality, public art, cultural policy, and digital platforms. As a writer and photographer, he has pioneered new methods to register the complexity of graffiti and street art, including its rise as cultural heritage, challenges to documentation and photographic practices, the uses of bio-social paradigms, ficto-criticism, the analysis of data-rich environments, and its connection to white supremacism and the alt-right. His work is widely cited and has been translated into French, Italian, and Ukrainian. His most recent book is Instafame: Graffiti and Street Art in the Instagram Era (2019), published by Intellect and University of Chicago Press (2019). He is currently an Associate Professor at the MIECAT Institute in Melbourne, Australia.