In September 2023, I met Anderson Nascimento, better known among Rio de Janeiro’s pixadores and pixadoras as Rato, which means ‘mouse’. He showed me the city through his eyes, the eyes of a pixador. Soon after, I interviewed him at his home. Rato, who was founder of the pixação group Legionarios, loved to take risks; for writing his name he would climb precariously high above street level, but he would also crawl on the dirty ground on his hands and knees.

Rio de Janeiro bears his unmistakable signature, on inconspicuous walls, in peripheral neighbourhoods, on the city’s characteristic viaducts, but also in the bustling city centre. In a city deeply marked by social inequalities and spatial limitations, pixadores and pixadoras seem to overcome especially the spatial boundaries. Protected by the darkness of the night, they cross the borders of different city areas and leave their conspicuous marks all over the walls of Rio in a style they call Xarpi.

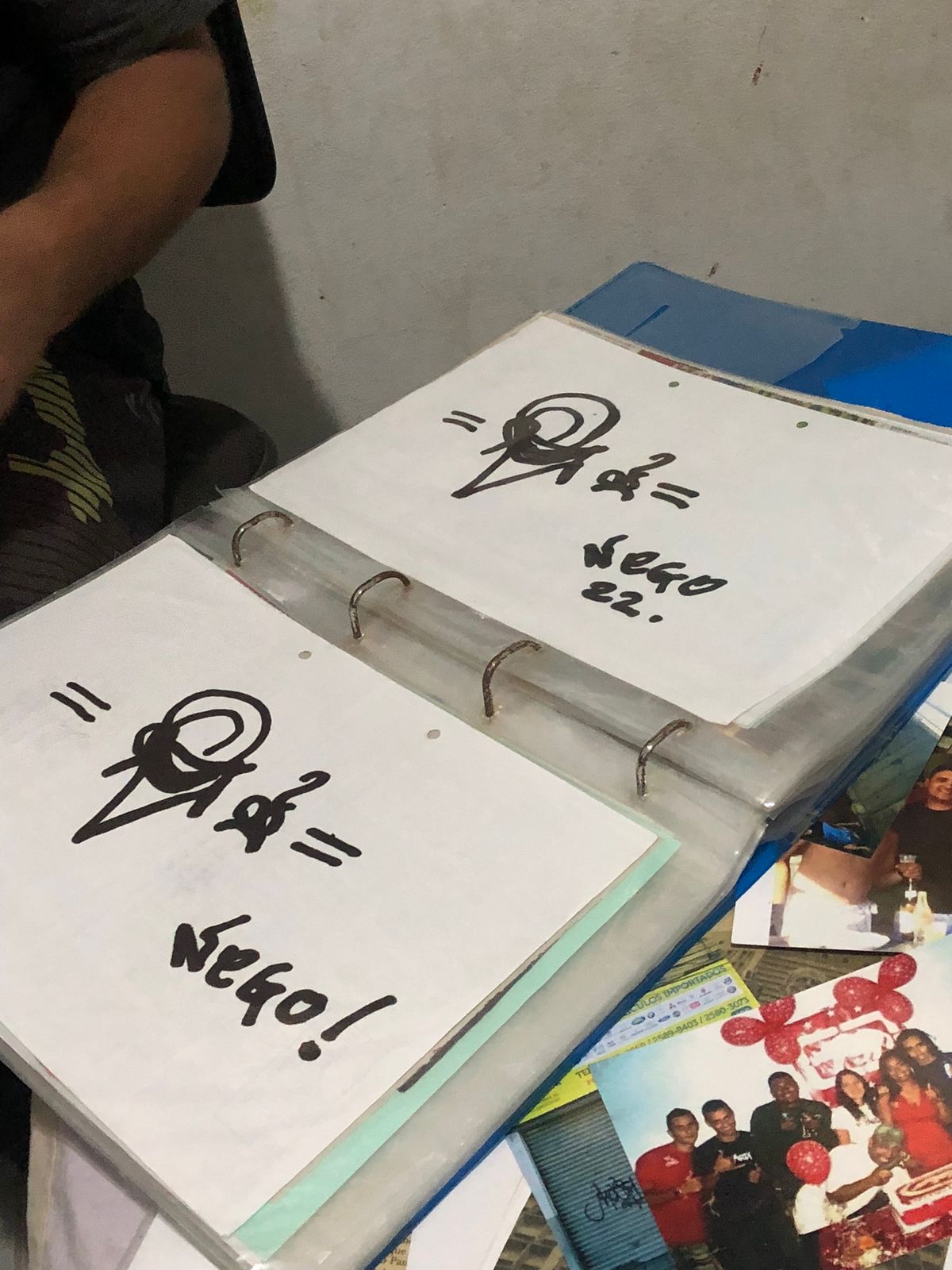

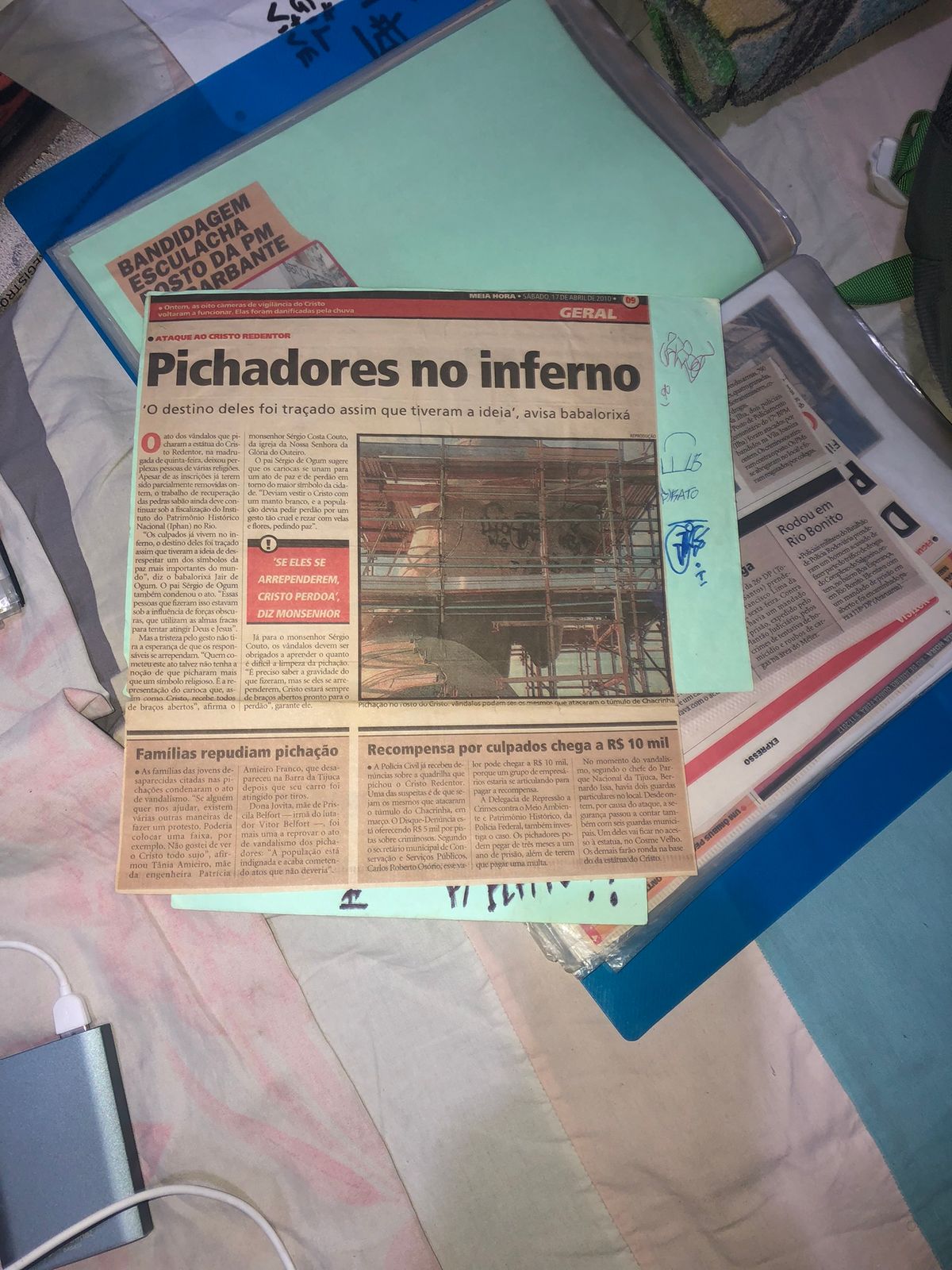

In this interview with Rato, we talk about his childhood memories of being called a camundongo and catching flying fire balloons, and his career as a pixador. We also discuss the tensions between graffiti and pixação, the relationship between art and pixação, as well as the archiving methods that have emerged from within the movement. Rato had amassed a unique collection of photographs and newspaper clippings from 2008 onwards, filling more than eight folders to the brim with Xarpi-tags from different neighbourhoods and gangs (the so-called Siglas).

Anderson ‘Rato’ Nascimento died on April 8, 2024 in Rio de Janeiro in a motorcycle accident. He was 33 years old.

Karl: Why did you start doing Xarpi?

Rato: My father worked a lot. I lost my mother when I was really young. At school, the boys would hide from their mothers in order to have fun, date girls and paint. They were always painting. And I went along with them. But I was very scared. Very afraid. I’ll show you some photos of me riding a mountain bike. Manoeuvring around, I was very audacious. But for these really crazy things like writing and climbing on walls, I was scared to death. One day they created a group here in the neighbourhood – the pixadores from Rio call this group Siglas – but they barred me from joining. They wouldn’t let me in, you know? That made me really angry. A week later, I got into an argument with one of them and ended up getting beaten up. The boy who hit me was working out, it seemed. Some time passed and I joined a jujitsu class so I could take him on. And I decided that I was going to be much bigger than all of them together in pixação. I was dead serious. A year later, I beat that guy up and kept on doing pixação. Now, many years later, none of these guys do pixação anymore, but I realised that I couldn’t stop doing it.

How do you differentiate between a xarpi that you think is well done, that is beautiful, and one that is ugly?

Firstly, the calligraphy. I think the calligraphy is everything. The xarpi has to be legible and well-crafted. And secondly, it’s about the guy’s attitude and style: what he’s done before and what he’s going to do tomorrow. If he started out wanting to attract the wrong kind of attention, or if he wants to do it right.

Can you give an example?

At the time, everyone wanted to have a big name, but not two guys called Bob and Gaspar. They just wanted to do their work quietly. They would go to locations where there was no one else around. In my early days, I used to write a lot at spots where the majority of the other pixadores and pixadoras were writing also. Nowadays, I think that’s very wrong, because Rio de Janeiro is very big, there’s room for everyone to write at different locations.

And your name? Why did you call yourself Rato?

Because I was quite… well, I’m still small, but I was even smaller then, and very white, and I liked catching large fire balloons in the air. Then they called me a ‘camundongo’. When I started to do pixação I said, I’ll just shorten that name. I’ll just abbreviate it so there are fewer letters.

What is a camundongo?

A camundongo is a small house mouse. So, I changed this to Rato to reduce the number of letters, to match the name.

And this ornament you make on your tag, does it have anything to do with the mouse?

No, but people keep saying that it’s the mouse’s tail.

Yes, I thought so too.

It’s because when everyone starts, they make a very childish ornament to their tag. Mine, over time, just got tighter. Then it ended up like this.

But is it important to have an ornament in your xarpi [pixação signature] or are there some people who don’t use one?

It’s optional. Now, a lot of pixadores don’t have one and I think it’s better that way because then your name will fit everywhere. If one day you want to add on an ornament, you can. Gust for example doesn’t have one so, if he writes on a smaller spot, there will be room for his name, while mine will be squeezed in because of the ornament – but if he wants to use one too, he can. Over time, people create a symbol in their minds that becomes dependent on the ornament. After a while, you’ll have engraved that mark there, not just the letter.

Do the people from the pixação scene know you because of the archiving you do? Do they care?

They think it’s important, because you have to be patient, right? Every day you have to look at the newspaper, buy it, cut out the articles, you know?

You have a lot of things in your archive, including ‘folhinas’, right?

Yes, here I have a folhinha, and each folder is a region – Baixada, West Zone, North Zone. Then I organise them by signature, and I keep two sheets of each one. Everyone asks me, why two instead of one? It’s because you never know what tomorrow will bring. I’ve seen a folder like this sell for over two thousand reais. There are groups that know how important these archives are and they offer to pay for this, so you never know what the next day will bring. If one day I needed to sell, I wouldn’t just have one sheet, I’d have two of each, you know?

You also go and take the pictures yourself?

Yes. I take pictures of the actions, buildings, and different siglas, pixadores, and pixadoras. But this is my personal collection, which I like to keep. Here’s me and Sunk. Me and Kim. And me alone.

What is the difference be-tween graffiti and pixação? In Germany, we don’t know the difference. Pixação would be called graffiti too.

No, we’re arteiros, right?

What’s arteiros?

We screw things up, you know, we get up to a lot of mischief. We like to… how do I put this… challenge the system. Whereas people doing graffiti make art.

And you don’t make art?

No. What we do is rustic art. Very rustic. [laughs]

But why do you think the people in Brazil don’t like pixação? Because I mean, they even like graffiti…

Because graffiti is colourful. Graffiti artists do something beautiful. Pixação is only beautiful to us. There are names that even us pixadores find ugly. Mine, for example, I find extremely ugly. Seriously!

Why do you use it then?

Because when I came up with it, I didn’t have much creativity. Nowadays I’m more into irreverence. But sometimes I see a xarpi and think, ‘holy shit, that’s a beautiful letter’.

Don’t you think it’s difficult to be a pixador?

It depends on your style. If you like to write on high buildings, there will come a time when it’s inevitable that you’ll face a risk. It could even be fatal, as it was for some of my friends.

So, you say it’s not art, that’s fine, but you still have to be creative, don’t you?

Yes, just like the phrases we put next to our xarpis. There have been places where I didn’t even want to do pixação, I just went up to them because they would be ideal spots for writing only the phrase. A phrase I use is a saying that goes, ‘a rat is a rat in any sewer’.

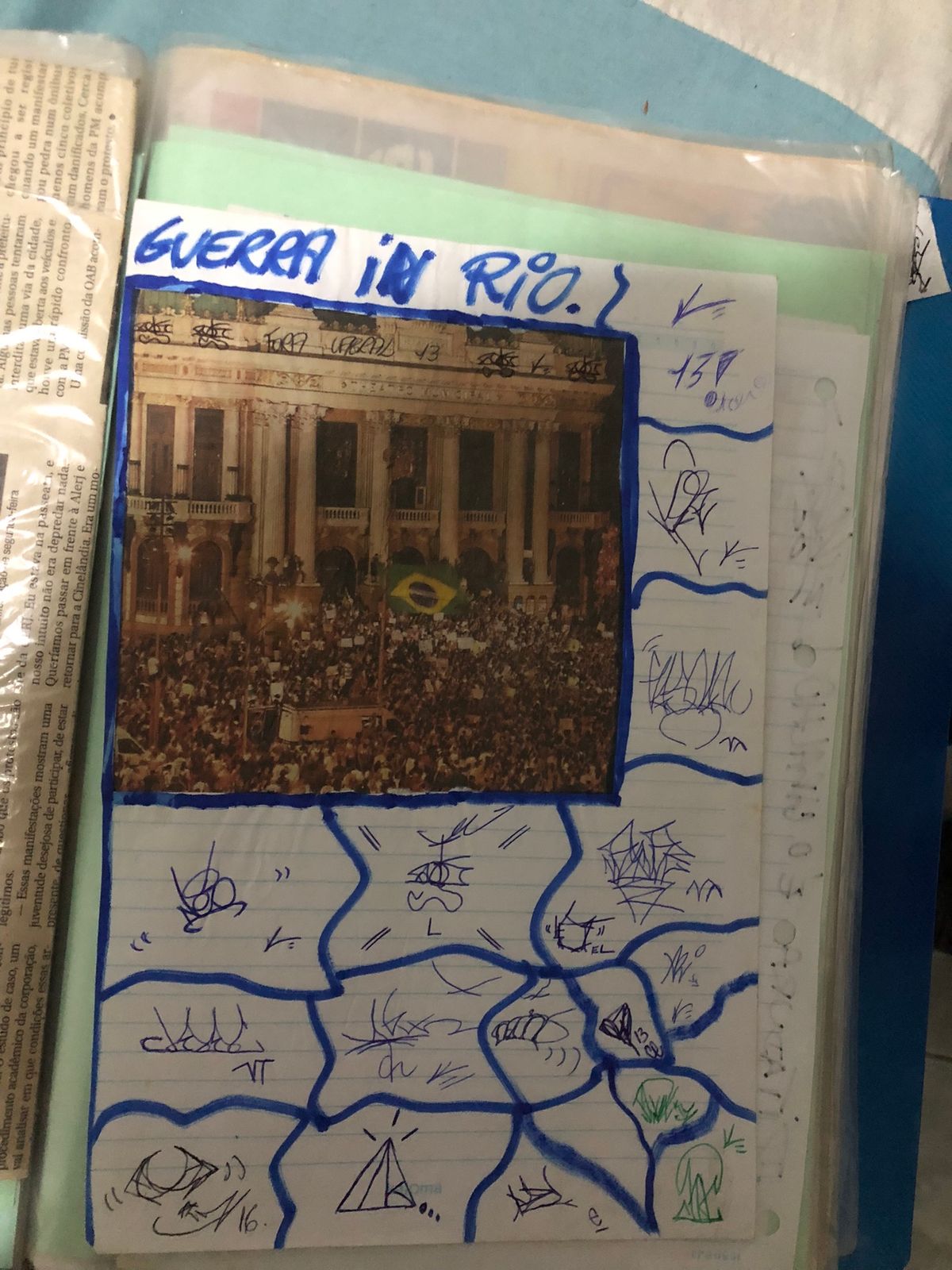

And do you think there’s an affinity between pixadores and those participating in social protests?

Yes, there is. The pixadores wave started with protests. [shows photo]

So, don’t you think nowadays it’s also a protest? Even if it’s not so obvious?

No, nowadays I think it has become more of an addiction. For everyone.

Para meu amigo Ratinho. Fique em paz.

Maëlle Karl is a Research Assistant on SFB 1512 ‘Intervening Arts’ at the Free University of Berlin, Germany in the project ‘Postautonomous Artistic Interventions in Argentina and Brazil’. She works on Pixação, an artistic practice related to graffiti and tagging in public space in Brazil. Maëlle Karl completed her BA in Translation and Cultural Studies at JGU Mainz in 2017 and then began an MA in Interdisciplinary Latin American Studies with a focus on Gender Studies at the Free University of Berlin. She wrote her master’s thesis in Rio de Janeiro in 2019 on art collectives as a space for transformative and decolonial processes.

- 1

A Pixação signature/tag in Rio de Janeiro is also called a xarpi.

- 2

Launching large fire balloons called ‘balão’ is an old tradition from Rio de Janeiro, which has been banned since 1998 due to the high risk of fire, but is still a popular practice, especially in the Zona Norte.

- 3

Papers pixadores collect, similar to blackbooks in graffiti culture.

- 4

Around €165, or $180.