For over 40 years the concept of fame – as in subcultural recognition and celebrity – has been the self-evident answer used to explain the driving force behind the hows, wheres, whats, and whys of subcultural graffiti. Still, the concept of fame itself is all too often left unproblematised. In this talk, cultural criminologist Erik Hannerz approaches fame less for what it is and more for what fame does, arguing that fame works to materialise collective emotions, ideals, and boundaries that are otherwise ephemeral and intangible.

Erik Hannerz: Ever since I started researching graffiti some ten years ago, I have been reluctant to use the concept of fame. Mainly because I am allergic to the unproblematic transferring of a subcultural concept into an analytical one.

What makes perfect sense to subcultural participants often appears as idiosyncratic when approached from a theoretical point of view, for the simple reason that what works within the subcultural does not have to make sense outside of it. Analytical concepts, however, have to do that.

Still, lately I have begun to rethink my use of the concept of fame. Criminologist Jack Katz asks us to investigate what crime does – what does an individual achieve through stealing a bike, dealing drugs, or beating someone up? And Katz does so by stressing the phenomenological aspects of crime and deviance – what and how the crime makes us feel?

So, I started going through the literature on graffiti as well as my own interviews and fieldnotes, focussing less on what fame is and more on what fame does. What can fame tell us of how subcultural graffiti is experienced and expressed?

In this talk, I will outline a somewhat novel approach to how we can understand the concept of fame, and how such a refined definition can work to capture how graffiti is made sense of as a collective activity. I will point to how fame works to provide a material and physical shape to the otherwise intangible. Drawing from the cultural sociology of Emile Durkheim I will refer to this as a totemic principle – that it is through the physical representation of the sacred – the totem – that participants come to experience and express themselves as a group.

I will do so by trying to argue less against the previous research, and by trying to point more to how such a refinement of the concept of fame makes it possible to read into earlier works. The totem provides an existential and affective aspect to subcultural doings and beings, while at the same time distinguishing and maintaining a distance to the outside:

It is by shouting the same cry, saying the same words, and performing the same action in regard to the same object that they arrive at and experience agreement (Durkheim, 1912 [1995]: 232).

Nevertheless, I will have to start by arguing against the previous research – so much for Mr Nice Guy (that lasted for literally ten seconds!) – because what bothers me is how fame is too often used to simplify subcultural graffiti, suggesting an instrumentality. For example, Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant write in Subway Art that fame – as in prestige and admiration – is ‘the repeatedly stated goal of graffiti writers’. Graffiti, they argue, is a competition for visibility, and fame is the result of succeeding in this game:

Getting fame is the repeatedly stated goal of graffiti writers […] Once a writer is ‘up’, he finds himself on a treadmill. In order to get fame and rise to the top of a multitude of competitors, he must get up over and over again. He is then rewarded by prestige and admiration – satisfactions he finds hard to part with (Cooper & Chalfant, 1984: 28).

There are numerous examples of graffiti being defined as a game of fame where visibility is the superordinate measure of worth, and the point of graffiti is to get your name up. As such, other aspects such as style, risk-taking, and control are explained as mere means to achieve such visibility. Standing out through style, showing technical skills, hitting hard-to-reach spots, or being the first to hit a particular place, are all thought to simply increase visibility. Other examples of this are the dissemination of your work to a larger audience such as through police reports, mass media, subcultural magazines, or Instagram, which in consequence, move you up in the game for fame.

All this assumes that graffiti is highly individual and highly rational. The communicated reason why graffiti writers would make up names, write them in style in places they are not allowed, risking their health, freedom, and economy is simply to compete for visibility so as to gain fame:

Fame, respect and status are not naturally evolving by-products of this subculture, they are its sole reason for being, and a writer’s sole reason for being here (MacDonald, 2001: 68).

As such, previous research paints itself into a corner, pun intended. Doing graffiti without attempting to become the biggest, most stylish, boldest, or the first becomes rather hard to address without pointing to this as less committed or less meaningful. It’s the same with graffiti that is done in less visible, less daring contexts.

This is so, even though there is plenty of research that suggests otherwise. For example, Malin Fransberg shows, in her work on Finnish train writers, how visibility is something potentially negative, and how these train writers exploit the invisibility forced upon them by the buff, so as to pursue secrecy and exclusivity. Similarly, Ronald Kramer has provided a thoughtful critical analysis of legal graffiti.

Fame as capital

Interestingly, previous research attempts to explain the diversity in how and where graffiti is done, through fame. Richard Lachmann, for example, argues that there are two aspects to fame – one that is based on saturation and quantity, and one that is based on style and aesthetic skills – and that the first gives rise to the second. Quantity leads to quality. Nancy MacDonald even talks about this as a graduation, the young beginner pursuing quantity and fame, so as to be able to ‘graduate’ into a more style-oriented career that is less wild and demanding.

Fame, argues MacDonald, works as a ‘highly valued wage’ that validates the dedication and sacrifice of writers, allowing them to relax or even to cash in on their fame, for example within the art world. The idea of graffiti as an alternative career is almost as old as graffiti itself. That it constitutes a possibility for young poor writers – often from a minority background – to become artists or designers.

Gregory Snyder writes:

Graffiti writers who have built a reputation and have avoided (for the most part) arrest find that as they age they have the option of using their talent, knowledge, and fame to transition into an adult career (2009: 44).

The move from tags and quantity to fame, and then from fame to style and galleries, is argued to make this possible.

But – if you allow me to play the devil’s advocate – I would argue that the previous research implies that the primary reason for doing graffiti is to be able to stop doing graffiti. That the goal of the game would be to stop playing. To grow up, graduate, and cash in.

To be sure, graffiti writers do at times become renowned artists or graphic designers. We can all name quite a few. But there is more convincing empirical evidence of this being due to competencies acquired through doing graffiti than of this being a matter of a transferral of fame. What makes a writer a great artist is less their subcultural fame and more their aesthetic skills, creativity, flexibility, being able to work under pressure, support from parents and art teachers, class background, etc.

Capital thus risks being mistaken for habitus.

‘INSTAFAME’

‘CHEAP FAME’

‘FAME WHORES’

The definition of fame as a form of capital also suggests that fame is something that can be measured objectively, as it introduces commitment as something in between visibility and fame. Of working hard and paying your dues. As such, fame that is earned without this commitment, as in becoming famous through a single photo or video on Instagram or through appearing in a news article, is addressed within the subcultural as cheap fame.

Again, subculturally, this makes sense. But from an analytical point of view, this is trickier. Although there are important studies such as those by MacDonald and Fransberg, that point to the gendered aspects of how commitment is used to include and exclude, and how non-male writers are dismissed on the basis of cheap fame, the term cheap nevertheless suggests that there is something that is real fame, and real commitment, and that this is something that can be studied independently from the subcultural.

Still, reading the comments section on any random graffiti post on Instagram is usually enough to realise that even graffiti writers have problems agreeing on what is real fame or true commitment. What is fame for one writer is cheap fame to another.

What about fun?

The problem, I will argue, is that fame is assumed to be a highly individual effort, rather than a collective one. And that this stress on instrumentality and the competitive element takes away the passion and the fun. To be sure, the participants I have interviewed over the years also note that graffiti involves a competition for space, for visibility. But it is a game you play to play, not to win. What matters more, they argue, is friendship, creativity, fun, thrill, and the collective.

This is in line with other research on subcultural groups who voluntarily pursue risks –- for example Jeffrey Kidder’s work on parkour or bike messengers — that stresses how these activities relate to identity work, self-control, and self-confidence, making friends, and seeking thrill, or excitement.

Or why not consider research on sports and arts? My daughter plays handball, and she dreams about making it to the national team and becoming famous. But she would laugh at the remark that the sole reason for playing handball is fame. To her it is about the fun, the passion, and the camaraderie. Why would graffiti be any different?

Previous research on graffiti does at times mention the aspects of fun and passion. Yet when they do so, they keep fun separated from fame — the competition for fame is considered the real and serious aspect, and fun refers to the social aspect.

But we don’t need to complicate things. We don’t need to come up with a formula of how saturation, style, and commitment relate to fame. We don’t need to approach graffiti as different from other subcultural groups. If we let go of the trees, we might be able to see the woods.

And if we ask what fame does, it becomes obvious that its elementary aspect is that of including, affirming, and collectivising. Of making the individual feel part of something.

PLAY!

From a sociological point of view, play is defined as voluntary and self-contained. It only makes sense within play.It rests on the desire to participate and on the internal rules that specify what should be done, and how and why this is important. From the outside, play is thus seen as largely irrational and unproductive. But play is transformative for the players. It enables them to temporally and spatially escape a prescribed order.

Hide and seek is a perfect example.It can be initiated at any time by someone merely stating it,initiating a way of thinking that we most often do not adhere to – hiding from our friends, and hoping they will fail to find us. Graffiti constitutes an extreme version of hide and seek. It is disembodied play. Graffiti, as noted by MacDonald, hides in the light. Writers know about other writers through their writing, despite never having met. To be recognised as a fellow writer refers to a collectivisation of the individual, being included as part of the play, and as adhering to the rules. This is perfectly illustrated by the graffiti way of greeting someone you don’t know: ‘Whatchu write?’

Craig Castleman (1984) offers a brilliant example of this in his story of Stan 153:

Tie 174 said to me. ‘Listen, let’s go up to the Coffee Shop.’ I didn’t know what it was, but he said, ‘Come up with me and I’ll introduce you to some people.’ I walked in and I saw all these guys all over the place and I said, ‘Wow, look at all these people. Who are they?’ There was a tough guy with a scar across his face; we called him Zipper Lip. He used to write Pearl 149. He walked up and said, ‘Whatchu write?’ I said, ‘Stan 153.´ So he said ‘Stan who?’ And I said ‘Stan 153.’ ‘DGA!’ He yelled it out across the coffee shop, and everybody immediately focused their attention on me. I was like, ‘Who, me? I’m an artist too.’ But at that time I wasn’t an artist. I was just a little toy, a DGA.

The last part is telling, having to accept that you are not fully included, a feeling of not truly belonging, of not getting around, a DGA, a little toy.

Stan 153 continues:

And it went on for two or three hours, signing books, and then Tie said, ‘Come on. it’s time to leave.’ And I said, ‘Where are we going now?’ ‘To the Concourse.’ So I said, ‘Concourse?’ because I was from Manhattan and didn’t know too much about the Bronx. So I went to the Concourse and I went through the great humiliation again of ‘What’s your name.’ ‘Oh, I’m Stan 153.’ ‘Who? DGA!’ When a train came in they said, ‘Your name on that train?’ And I said, ‘No, my name ain’t on this line.’ And they said, ‘What line is your name on, the number Z?’ And I said, ‘No, it’s on the 3s.’ And they said, ‘O.K., we’re going to the 3 line. If your name’s there, you can hang out. If it isn’t, ‘bye guy.’ So we went to 96th Street and Broadway. It was me, Topcat 126, El Marko, Bug 170, Phase II. I didn’t know Phase II then; he was just a guy everybody seemed to idolize. So we’re at 96th Street and after a half an hour of waiting, my name came up. ‘Is that your name?’ It was an ugly piece of gook on the side of the train, but I said, ‘That’s my name! That’s my name!’ ‘O.K. You can hang out.’ When they said that, I said to myself. ‘I’m accepted. The Bronx people accept me!’ (Castleman 1984: 85–86).

Similar to the earlier quote, what is here being stressed is the affective aspect of belonging. It refers to being seen in its most elementary form: of being validated, validated as having an existence. Stan tells of how he was twice denied inclusion, referred to as a DGA (‘Don’t get around’) as in someone they have never heard of, and thus recognised as partly excluded from the subcultural. It is only through pointing to his name on a train car – one can imagine the relief – that he gains their acceptance. This is a beautiful quote as it captures a move from the unknown, uninitiated, excluded – DGA – to acceptance, with Stan’s pride being obvious. They know I write, therefore I exist. We play so as to become part of the play, rather than as a game.

The graffiti writers I have followed would tell similar stories of inclusion, of being out with a senior writer they had never met and the pride they felt when that writer already knew their tag. But they would also tell of the opposite – of being ignored and refused permission to participate.

Feelings such as fun, passion, love, and humiliation are thus an intimate part of fame, not something separate. They are directly tied to the collaborative and existential nature of writing.

Writing both as a noun and a verb is the totemic object of subcultural graffiti

Writing is the physical form through which the subcultural is expressed and experienced as a collective. And as with other sacred objects, such as the emblem of a clan or the flag of a country, it includes, through encompassing – and excludes, through denying – the feeling of belonging. This makes subcultural graffiti different from other forms of graffiti – such as, for example, Michelangelo’s graffiti in the cellars of the Medici Chapels in Florence; Rimbaud writing his name on the Temple of Luxor; or Ellen at Lund university who wants to address her presence to everyone(Figure 3).

All of these forms of writing are public in the sense that they invite an outsider to participate. We might not know Ellen or care whether she is ‘in da hauz’ or not, but we can read and understand it. Its message is straightforward. It expresses an already existing identity. Ellen’s existence, and even more so Rimbaud’s, is not exclusively defined by their writings.

Subcultural graffiti, however, is.

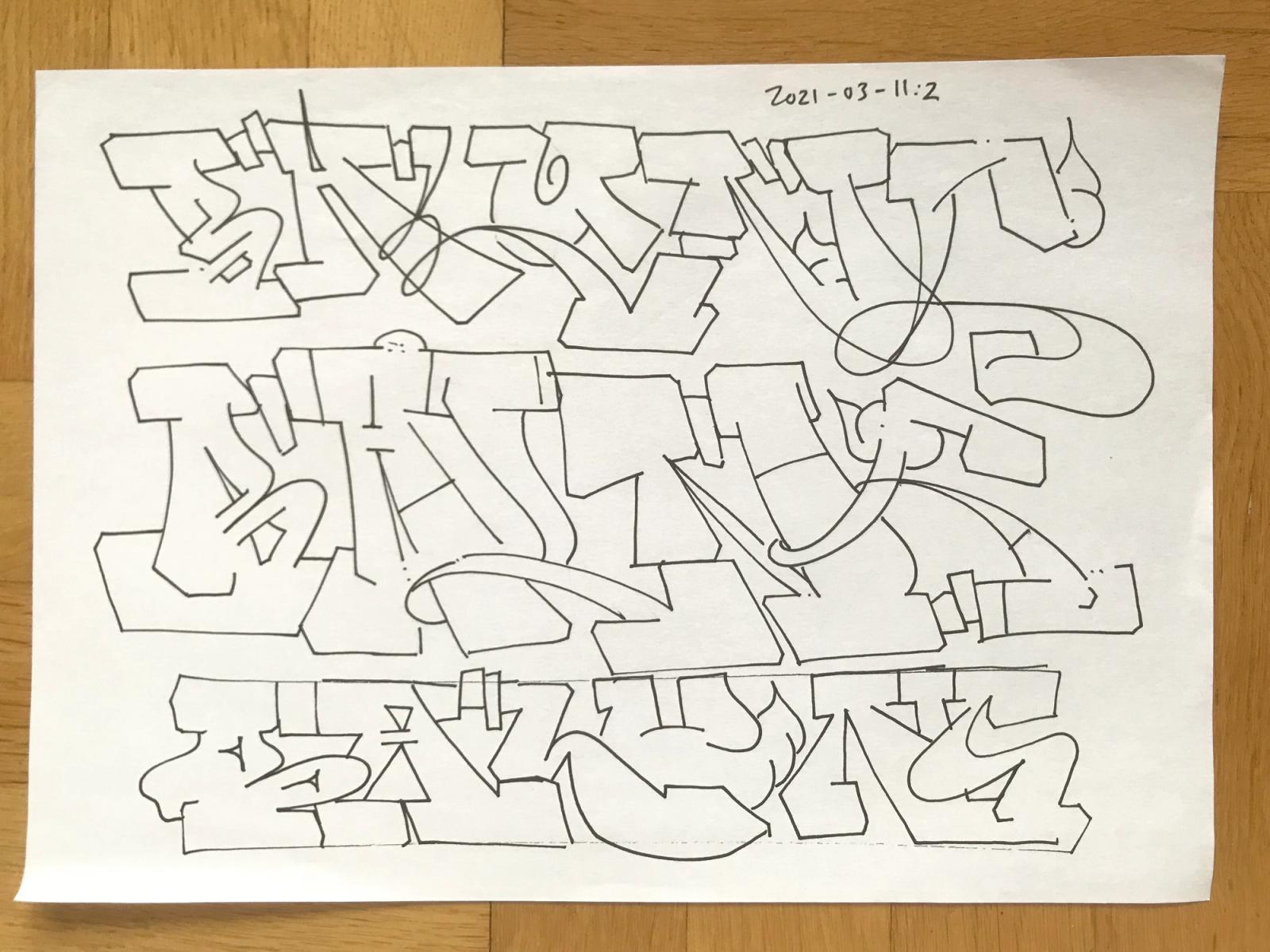

It is performative, in the sense that there is no doer prior to the deed. Tobias Barenthin Lindblad (2008: 12) captures this in saying, ‘to be sure graffiti writers create tags, but the tags at the same time create the writers.’

Uzi becomes the writer UZI through the writing (Figure 4).

The form is the content. The content is the form. Or if you prefer: the medium is the message. Contrary to Ellen in da Hauz or Rimbaud, UZI does not exist without this writing.

A further difference is the attempt of subcultural graffiti to exclude a non-initiated outsider. The sanctity of the totem of writing means that belonging is ritualised through rules and prohibitions. Partly through what and how to write – a unique name, written in style, in various forms (tags, pieces, throw ups, etc.) – and partly through how to read the writings. Again, a collectivisation of the individual.

Deciphering tags, throw ups and pieces is somewhat similar to reading black metal logos. It takes an acquired competence of being able to tease out the letters. As Kase 2 notes to the camera in Style Wars:

Sure, l got styles already that’s more complex that nobody know about. I mean, super-duty tough work. See, this is just semi-like, what l would call it. But, if I really get into it and start camouflaging it, l don’t think you even be able to read it.

Furthermore, to read is to understand. And, similar to belonging, understanding is to be able to piece the partstogether into a whole. How different forms of writing U-Z-I become the writer UZI, or – as seen in Figure 5 – how different forms of writing B-A-L-U-N-S become the writer BALUNS. Every single public bathroom in Sweden has the Swedish word for cock written in it: kuk (Figure 6).

However, I doubt that anyone would read those scribbles and go: Wow KUK again. Shit that KUK is really up.

The point is that to read in graffiti is to connect. And to connect is to include. Of collectivising the individual. Objectifying the subject. As when Stan 153 is asked, ‘is that you on that train?’

Is. That. You. On. That. Train?

Writing graffiti includes as it excludes the outside. They see it, they might be able to read it, yet they can never understand it.

And this goes for all subcultures. I remember the first time I, as a young punk, heard and liked Black Flag. There is separation here in time between hearing and liking. I had listened to Black Flag for months with my friends and I had told them and others how much I loved Black Flag. During this time, I had questioned myself, I had questioned others who claimed to love it too, as well as questioned the band itself. As their music appeared to me as pure noise. But the feeling when I actually understood it, when I wanted to listen to it – that was priceless.

Fame in its most elementary form constitutes the recognition of such a feeling as valid. The feeling of being part of something bigger.

To paraphrase Emil Durkheim:

It is by shouting [writing] the same cry [forms], saying [reading] the same words, and performing the same action in regard to the same object that they arrive at and experience agreement.

This aptly summarises this first aspect of fame. Its elementary form of drawing and bonding participants together, accomplished through the feelings that writing evokes in participants.

Fame as a totemic principle suggests a transformative and transcendent character through writing – participants lose themselves in the collective. As such, fame is a process, but not in the sense of the previous research’s focus on a subcultural and individual development from toy to king.

Rather it is a collective process. Something that is negotiated and validated. As Joe Austin (2002) points out, fame is collective in the sense that it is something that is told, re-told, and mythologised.

Through writing, participants come to belong. Through stories of writing, such belonging is strengthened.

Fame as the iconic

This brings me to my second point: fame as the iconic. Stories are crucial to understanding graffiti: writers sharing their own experiences as well as the extraordinary adventures of others. Who has done what, with whom, who was first? Or who has the worst history of getting caught? As documented by Rae and Akay in their great book Getting Caught.

Let’s return to the affective aspect of fame as belonging, pride, acceptance, self-worth. Other feelings such as passion, thrill, love, dedication, and creativity associated with the doings of graffiti are harder to grasp. Same with ideals. But stories give a physical form to such feelings. They make it possible to express a fear of getting caught, the thrill of fooling the guards, the beauty of a trackside wall at dawn. But as such, stories also individualise the collective. The subject of such stories come to represent what graffiti is and what graffiti should be.

UZI is not just UZI, in the sense of a recognised part of a whole, to many writers UZI is rather that very whole they feel part of – a subcultural saint – not just recognised but rather renowned. Immortalised through books, interviews, and videos.

If fame as belonging is the inward form of the subcultural, fame as the iconic refers to the outward form. Jeffrey Alexander (2012: 28) refers to this aspect of the totemic principle as iconicity, in the sense of the set apart, that which at the same time represents and singularises:

Powerful icons combine the generic (they typify) and the unique (they singularize).

Or, as notes Ian Woodward and David Ellison in the same volume: iconic status refers to a condensation of ‘the supreme object of a particular class’ and an expression of the collective:

The icon as a ’symbolic condensation’, a thing that holds within its material form a cultural, moral meaning […] pointing to an icon’s taken-for-granted status as both the supreme object of a particular class and as concrete expression of a collective representation (Woodward & Ellison, 2012: 157).

Fame as in the iconic singularises so as to make participants feel and express collective ideals.

Let us take Danish graffiti icon KEGR (Figure 7), present in almost all my interviews as part of stories:

KEGR, who you know I remember from 1995, when he owned the Central Station in Copenhagen, all the way into the station, had tagged all the sides of the platforms, and with fucking beautiful tags. And now, he still owns the Central Station, what an amount of work that is. It such a headstrongness, it’s impressive, I mean, many had, I mean he could just withdraw, he has the ways in, he knows all of those who do more gallery stuff, he could easily live on that, but he still hits the streets and I find it so cool that determination, and how you see his tags in fucking weird places, he’s been fucking everywhere.

KEGR has been renowned within European graffiti since the 1990s for his style, his trains, and as the above quote testifies, for literally saturating the city with his name. To the point that there is a saying in Swedish graffiti that you are never more than 500 metres from a KEGR-tag.

To be sure, we could argue that KEGR is iconic for what he has done – his commitment to the subcultural, his visibility – a well-earned wage that could even be transferred into the art world. This is the assumed meritocratic and individual aspect suggested by the previous research.

Yet, as noted by Jacob Kimvall (2014), masters are built through stories and materialisations. Subway Art and Style Wars established a canon of masters, all while sending other pioneering writers into oblivion as they were excluded.

KEGR is KEGR not on the basis of what he is or what he has done. KEGR is KEGR because of what he has come to represent. KEGR is KEGR because his writing becomes a means for participants to express subcultural ideals, subcultural feelings, and subcultural boundaries. The quote above says more about the individual interviewed than it does about KEGR.

Through stories, pictures, and videos of the iconic, it is possible to express and experience the subcultural in a shared way. They remind participants of what the subcultural is and what it should be. It is a simple and direct way of expressing what kind of writer you are, but also a convenient way of negotiating awe, fear, or excitement.

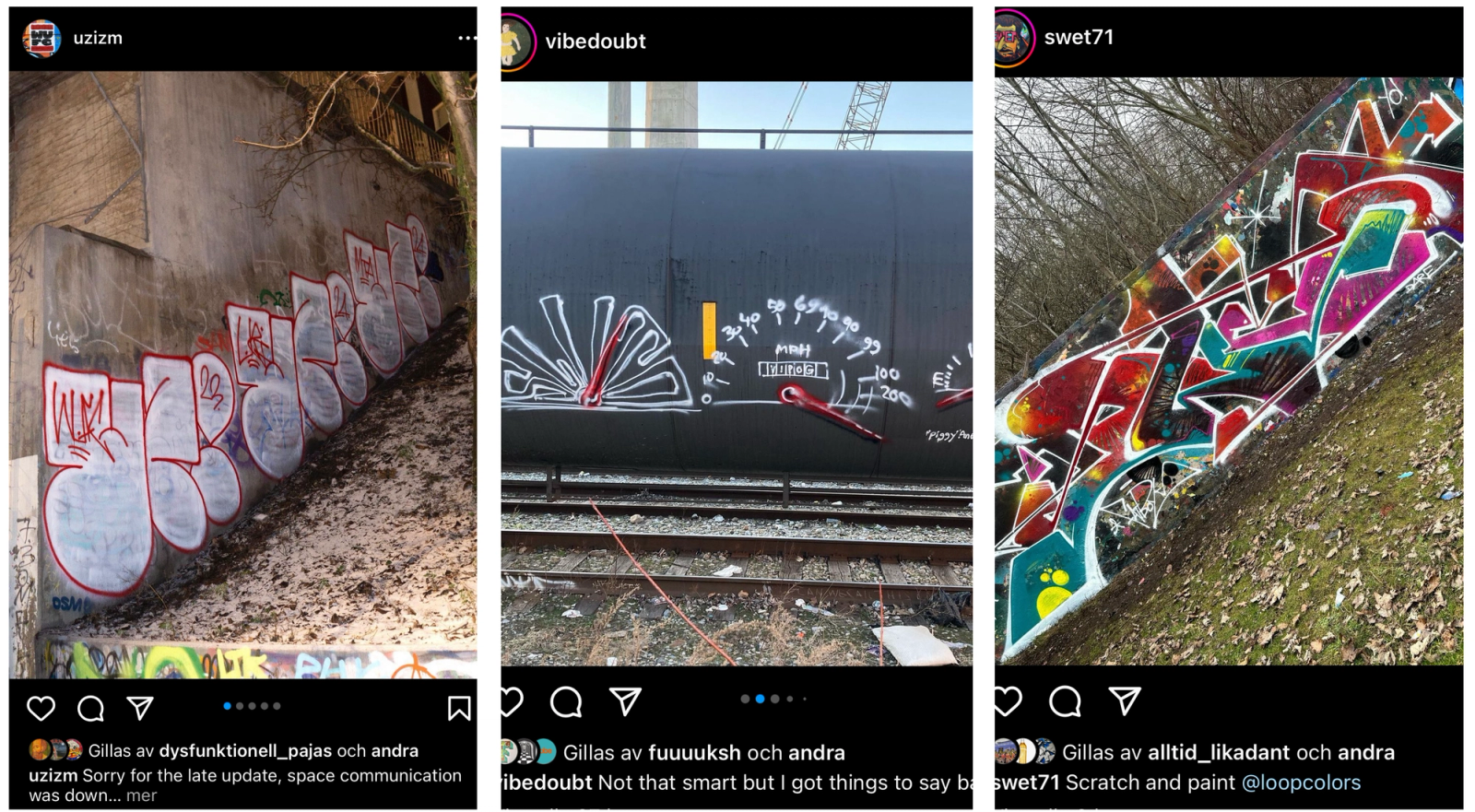

That is also why Instagram has become such a stronghold within subcultural graffiti, not just because of its image-based format, but also how it facilitates and makes public a discussion that was previously limited to jams or discussions with your friends(Figure 8).

Regardless of whether you admire Sluto’s incredible freight pieces, UZI’s throw ups or Swet’s frantic style, Instagram does not just offer a window, it offers an online shrine – where participants can express themselves together and in so doing extolling and reinforcing both subcultural ideals and their excitement.

Instagram of course also offers the opposite – i.e. a public shithouse – and yet it still refers to subcultural boundary work. Negative representations, as in accusations of the fake, the cheap, the toy or DGA are but just another way of materialising collective ideals.

Conclusion

So, to conclude, I am not arguing that graffiti is a religion. The totemic principle should rather be seen as an apt metaphor for how fame becomes a basis for social organisation. A ritualisation of meaning, depth, and collective beings and doings.

To talk about the totemic principle of subcultural graffiti is to describe how participants are drawn together, bound together, and how they come to experience and express themselves as a subculture through writing.

Writing graffiti – that is name-based, style-based, repetitive, and through specific aesthetic forms constitutes the emblem of the group – is the flag of the subcultural, that which marks it off from other forms of crime, and other forms of illegal writing.

Fame, as I have argued, involves an existential joining of individuals into a collective.

Still, this phenomenological aspect rests on a narrative aspect, whereby individual writers come to represent subcultural ideals and feelings – in an outward form of this collective energy.

I have referred to fame as the collectivisation of the individual in the form of recognition and belonging, and as an individualisation of the collective as in the iconic. Still, these constitute two sides of the same coin. Accordingly, I agree with the previous research that fame is essential to subcultural graffiti. But not in the sense of an individual competition for attention, but rather as something through which the subcultural is felt, experienced, and made sense of.

The part here evokes the whole.

The totemic principle, as notes Durkheim, refers to a tangible representation of the group itself:

Here, in reality, is what the totem amounts to: It is the tangible form in which that intangible substance is represented in the imagination; diffused through all sorts of disparate beings, that energy alone is the real object of the cult (191).

It is through the principle of fame that subcultural graffiti worships itself.

That is the totemic principle of subcultural graffiti.

Erik Hannerz is a researcher and Senior Lecturer at the Department of Sociology, Lund University, Sweden, and a Faculty Fellow at the Center for Cultural Sociology, Yale University, USA. He received his PhD at Uppsala University in 2014 on a dissertation on subcultural theory, with punk as the main case. The last decade he has spent researching graffiti and especially its spatial aspects. Hannerz is the co-founder of Urban Creativity Lund, and coordinator for the master of science programme in Cultural Criminology at Lund University.

Alexander, J. (2012) ‘Iconic Power and Performance: The Role of the Critic’. In J. Alexander, D. Bartmański & B. Giesen (Eds.) Iconic Power: Materiality and Meaning in Social Life. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Austin, J. (2002) Taking the Train – How Graffiti Art Became an Urban Crisis in New York City. New York: Columbia University Press.

Barenthin Lindblad, T. (2008) Foreword in Cooper, M. Tag Town. Årsta: Dokument Press.

Castleman, C. (1984) Getting Up: Subway Graffiti in New York. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Cooper, M. & Chalfant, H. (1984) Subway Art. London: Thames and Hudson.

Durkheim, E. (1912/1995) The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Trans. K. E. Fields. London: Allen & Unwin Ltd.

Fransberg, M. (2020) ‘Spotting Trains: An ethnography of subcultural media practices among graffiti writers in Helsinki’. Nuart Journal, 2(2): 14–27.

Katz, J. (1988) Seductions of Crime: Moral and Sensual Attractions in Doing Evil. New York: Basic Books.

Kidder, J. L. (2013) ‘Parkour: Adventure, Risk, and Safety in the Urban Environment’. Qualitative Sociology, 36: 231–250.

Kimvall, J. (2014) The G-word: Virtuosity and Violation, Negotiating and Transforming Graffiti. Stockholm: Dokument Press.

Kramer, R. (2017) The Rise of Legal Graffiti Writing in New York and Beyond. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lachmann, R. (1988) ‘Graffiti as Career and Ideology’. American Journal of Sociology, 94(2): 229–250.

MacDonald, N. (2001) The Graffiti Subculture: Youth, Masculinity and Identity in London and New York. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rae & Akay (2014) Getting Caught. Rome: Globcom, Whole Train Press.

Silver, T. (Director) (1983) Style Wars [Film]. Public Art Films.

Snyder, G. J. (2009) Graffiti Lives. Beyond the Tag in New York’s Urban Underground. New York City: NYU Press.

Woodward, D. & Ellison, D. (2012) How to Make an Iconic Commodity: The Case of Penfolds’ Grange Wine. In J. Alexander, D. Bartmański & B. Giesen (Eds.) Iconic Power: Materiality and Meaning in Social Life. London: Palgrave Macmillan.