This is an edited transcript of a series of conversations between John Fekner and Susan Hansen, Queens, New York, July 8 – September 4, 2024.

In the late 1970s, artist John Fekner began a relentless crusade concerned with urgent social and environmental issues in New York City. The politics and energy of Fekner’s street-based illegal interventions also extended to his music – making a multisensory impact on the city.

Starting in the industrial streets of Queens and the East River bridges, and then in the South Bronx in 1980, Fekner’s stencilled messages appeared in areas that were desperately in need of construction, demolition or reconstruction. By labelling decaying structures and emphasising problems, Fekner’s objective was to call attention to the accelerating deterioration of the city by urging officials, agencies and local communities to take action.

These interventions were ephemeral and were never intended to last. They succeeded when the underlying conditions they made visible were remedied.

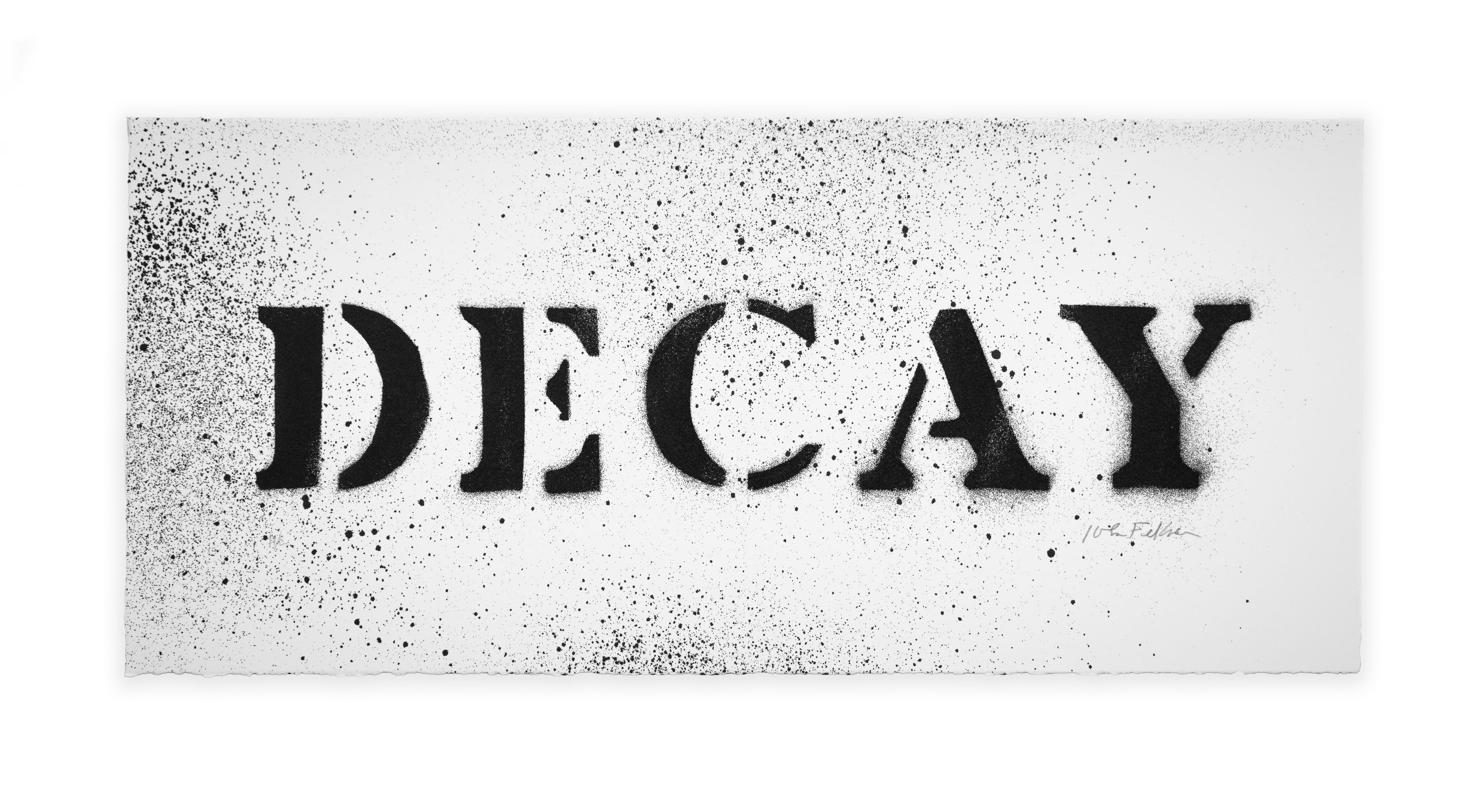

John Fekner: Most people think of the Decay series as being only about those huge stencils like Broken Promises – the South Bronx work. That’s the iconic image of the Decay stencil, co-opted by the 1980 Republican Presidential Candidate Ronald Reagan in the foreground. I guess that’s what people think of first. They’re big pieces. Those letters were three feet high!

What people may not know is that there were many other Decay stencils scattered across the city – at least 50 distinct interventions of different sizes, on walls, bridges and abandoned cars, between 1978–1983.

The lettering on my new Decay print (Bio Editions) is the exact size of the stencils I painted on the Queensboro bridge in 1979. When I did this piece, I had my workspace set up in the living room. My parents couldn’t even watch TV. There were piles of Kodak yellow slide boxes, and my stencils, and maybe they were already putting two and two together.

So, my father would go for the newspaper every morning. But this one morning, he came in with the paper and instead of reading it in the kitchen like he usually did, he just put it on my desk. He didn’t need to say a word. He just put the paper down.

And that’s how he first figured out what I was doing.

The Decay series was about calling attention to the infrastructural decay on NYC bridges. I was paying a lot of attention to my immediate environment and questioning why something was broken and not being repaired. I tried to emphasise the problem that other people seemed to block out of their vision – I aimed to make it more visible. I had started to notice that instead of repairing bridges, the city would first paint over them to cover up the rust and decay, rather than doing the structural work that was desperately needed. On some NYC bridges, parts of the concrete ceiling were falling down onto the roadway. They were crumbling and dangerous.

Because I could paint at high speed, I could repeat the stencils in one location, so you’d see ‘Decay’ driving onto the bridge, and at the other end of the bridge you’d see ‘Decay’ again – it wouldn’t just be in that one spot. I wanted to spread the word and make people think.

This was a very efficient process for me. My stencils were easily transportable. I spotted or hunted the locations first, and fit the message to the location, so that was all preparatory in terms of the locations that were chosen. But the painting itself was super quick, you know, it was in and out.

The city’s graffiti didn’t seem surreal to me at all, but the Decay stencils always had a sense of being surreal and unexpected interventions. These illegal stencils raised questions for the viewer, because they somehow looked official. For me, awakening this questioning fac-torwas really important. I wanted people to give some thought to this one word and its placement in their everyday experience.

The Decay stencils were all done illegally, at night, in my getaway car – I’ve not told this story before now. So, I would stop the car. I’d jump out, pull up the engine hood to look like it had broken down. And then I’d do the painting. With the hood up I wouldn’t be that noticeable. Sometimes I would stencil the Jersey barriers, the concrete barriers between highway lanes.

I mean, I was nuts. This was in the fast lane. I had my hazard lights on, but I still had to be super quick. I could be so fast because these were smaller stencils that I could paint real fast, and that was the unique thing about this work on highway barriers and bridges.

Obviously, I had a car, I had a crew, rarely did I do something completely by myself. You know, there were always the kids from the park or a few of my other friends. And they were like, 10 to 12 years younger than me. But they kind of looked up to me because I was a handball player. The real New York concrete streetball sports, handball and basketball, you know, one-on-one, singles, doubles and cutthroat. In 1974, before the stencil days, I would play at West 4th Street Courts where all the best amateurs from the five boroughs would come together to compete; Blacks, Whites, Spanish with music blasting in the background.

The politics and energy of my illegal street work extended to my music. During this time, I was also starting to write songs. Rapicasso was created from 1983 in various media including painting, music and video. It’s a tribute to Picasso. Like his love of utilising different media, i.e., painting, sculpture, ceramics and light drawings, I would use whatever material necessary to create a multimedia work in different forms of artistic expression. Using my LCD stencil plates, Rapicasso referenced Picasso’s Three Dancers and Three Musicians, with a focus on three breakdancers spinning on their heads and hands.

The lyrics to Rapicasso underline the integral connection between creative work on the street and new forms of musical expression. In 1984, I rapped, ‘Musicians were painting … Watch the street, see the modern art/It’s the present and future tied to his heart’.

In 1985, I was invited by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago to be part of their Oxbow residency. This was in Saugatuck, Michigan, which is on a lagoon – it’s a tranquil and beautiful place for artists. The students from the Art Institute would go there for the summer, which involved artist residencies, talks and lectures, and they would also do their own work. So, I went there for a couple of summers in a row, in 1985 and 1986.

My songs – like my stencils – started in Jackson Heights, at my parents’ apartment. But when I went to Oxbow, I brought my Roland EP-20 electronic keyboard, Synsonics drum machine and cassette recorder, and in the middle of the woods and the cabins, we created what would eventually become Concrete Concerto. This song was co-written with Sasha Sumner. There’s a video performance of Sasha playing the saxophone in the early stages of what was then called Sidewalk Shuffle.

Concrete People was a collaborative work with Dennis Mann that came out in 1986. Writing the lyrics was a year-long project. I stopped doing those kinds of projects because they were so time consuming – you know, you would have to use typewriter paper with white out. I don’t know how many pages I used to rework that song. It must have been 50 pages! So, it’s almost like a book in itself, because you’re constantly moving through variations in the lyrics, just to get it right.

Most of my work was inspired by being involved with late '60s peace movements and listening to protest songs, all those ideas carried in lyrics from people like Phil Ochs and Bob Dylan. From this, I got the whole idea of condensing everything down to one line. Just a single line.The whole idea of conveying something complex and dense into a single phrase, similar to Jenny Holzer. One sentence philosophy. But then I reduced it from a sentence, to two words, and eventually to one word, Decay.

Concrete People also comes out of that instinct, and as a response to what was happening during the '80s, with the media’s superficial valorisation of the ‘perfect body’ as the ultimate goal. Cher was doing fitness TV commercials, Jane Fonda’s workout videos were in every home, Physical featured Olivia Newton-John in a leotard transforming overweight men into muscular ‘hunks’, and Arnold Schwarzenegger was everywhere promoting an impossible body standard.

In response to this, I created Beauty’s Only Screen Deep, which features as a usable stencil bonus print in my new re-release album Idioblast 1983–2004. And the stripped-down version of this message is how Concrete People came about. The city’s surfaces are made of concrete. So, it was about looking at our society’s superficial aspects in those terms. The Concrete People stencils in public space were part of the project and featured in the music video collaboration with artist Andrew Ruhren.

During my Oxbow residency, instead of doing my usual one or two word stencils like Decay, Abandoned or Visual Pollution, like I would normally use on abandoned vehicles, I painted And The Detroit Wheels on this wreck of a van. On a surface level, this was a musical reference to Mitch Ryder’s blue collar rock band, but it was also a critical reference to our location. Detroit was the home of General Motors, and Chryslerand Ford, and all the car factories that have since closed. The cars they produced had a planned obsolescence. Back then, all the cars leaked oil. You had to carry around oil cans in the trunk of your car in case you ran low, and we all left dark puddles of oil wherever we parked, polluting the planet.

Although I was releasing records by 1983, there was very rarely a live performance of The John Fekner City Squad. We had fewer than five performances overall. We were all different people from different backgrounds – some were musicians, some were kids, you know, ‘non-musicians’. As an extension of Queensites, the group of teenagers from Jackson Heights: Dave Santaniello, Dave Lella, Maria Katsaros, Diana Pavone and Lorraine Lucas and others who assisted me with the outdoor stencil work, joined me to perform. It was kind of a big family. A bit like Joe Cocker and friends, you know, bring everyone, including the dogs, on stage!

The first major place that we played live as the My Ad Is NO Ad Band was back in February 1981 at Martha Wilson’s Franklin Furnace space. I was invited to do an installation and instead of just doing an installation, I told her I had been doing some music. So that was the first event with the Queensites kids who had been stencilling with me on the streets. But because some of them couldn’t play, we had to fill out the stage to make it look like we were real good – it was a happening!

Later, in 1987, we joined a lot of super interesting downtown people to play on the Franklin Furnace ferry on the Hudson, but we did not do many performances overall. There were some other rare other performances in this period that were sound-based. But these were undocumented, so they are now lost to time.

John Fekner (b. 1950) is a street and multimedia artist who created hundreds of environmental, social, political, and conceptual works consisting of stencilled words, symbols, dates, and icons spray painted outdoors in the United States, Sweden, Canada, England, and Germany. His work is held in numerous museum collections across the US and Europe including the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA; Museum of Modern Art, NYC; Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC; and the Malmö Museum and Skissernas Museum in Sweden. His work has also received recognition from the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York Foundation for the Arts, and the New York State Council on the Arts. https://johnfekner.com/

- 1

For more, see Fekner’s Environmental Stencils 77-79 video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k6sSr6njKIU.

- 2

A video of the 1987 Franklin Ferry event may be found at: https://vimeo.com/21830022.