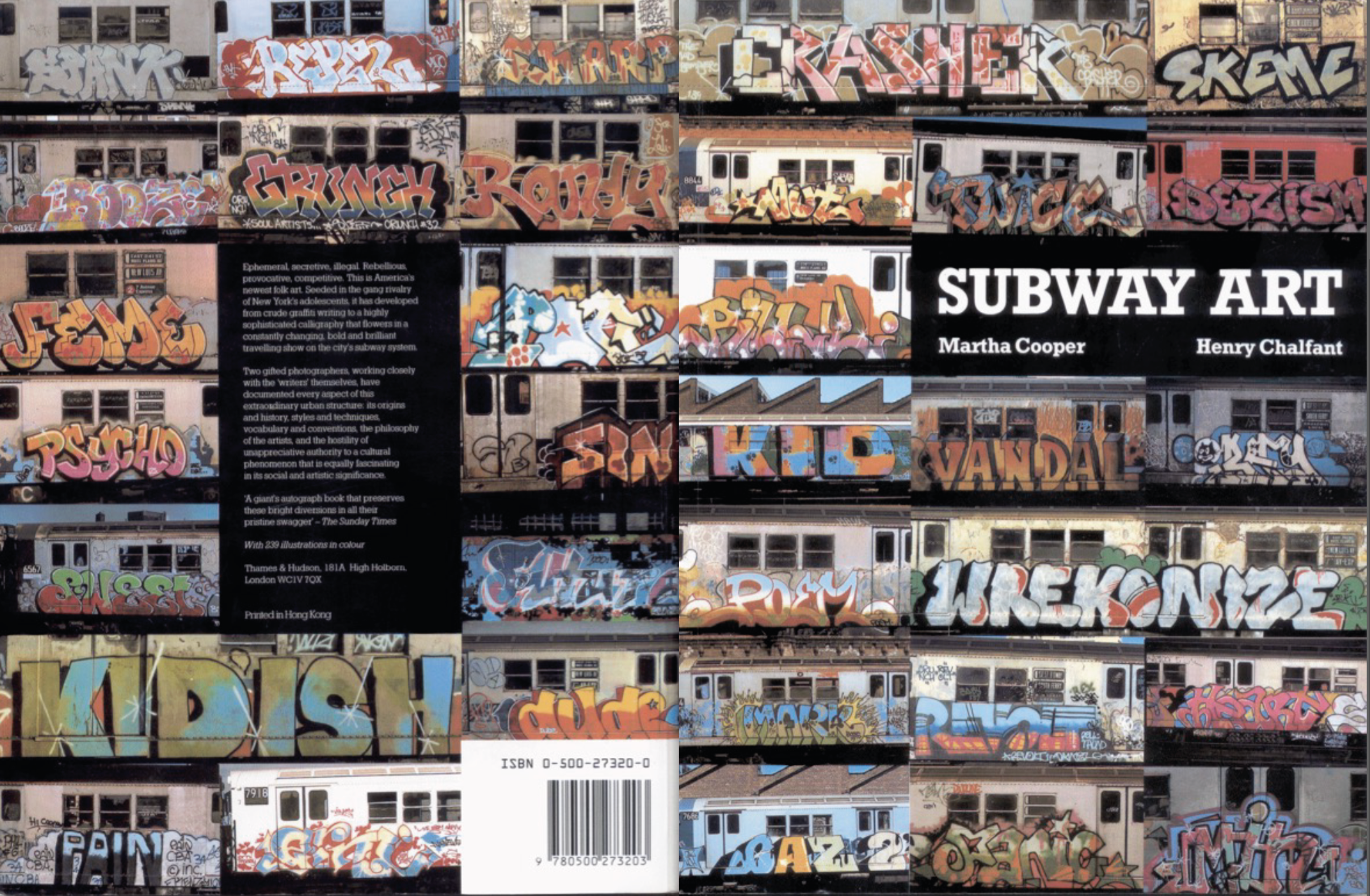

Little did Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant know in 1984, that the book of photos they so struggled to find a publisher for, was to become a huge and long-lasting success. With well over half a million copies sold worldwide four decades on (and a record many of them stolen from bookshops), Subway Art is commonly referred to as the Bible of Graffiti.

2024 marks the fortieth anniversary of Subway Art – a publication that not only helped salvage for posterity the imagery of a local graffiti counterculture, portraying happy and fun-loving Black and Latino youths expressing themselves artistically. It also proved influential to the extent that the sort of graffiti pictured – i.e. the visual language of hip hop – soon transcended New York to be duplicated and become dominant in large parts of the (Western) world. The pervasiveness of this form of letter- and name-based graffiti lasts to the present day.

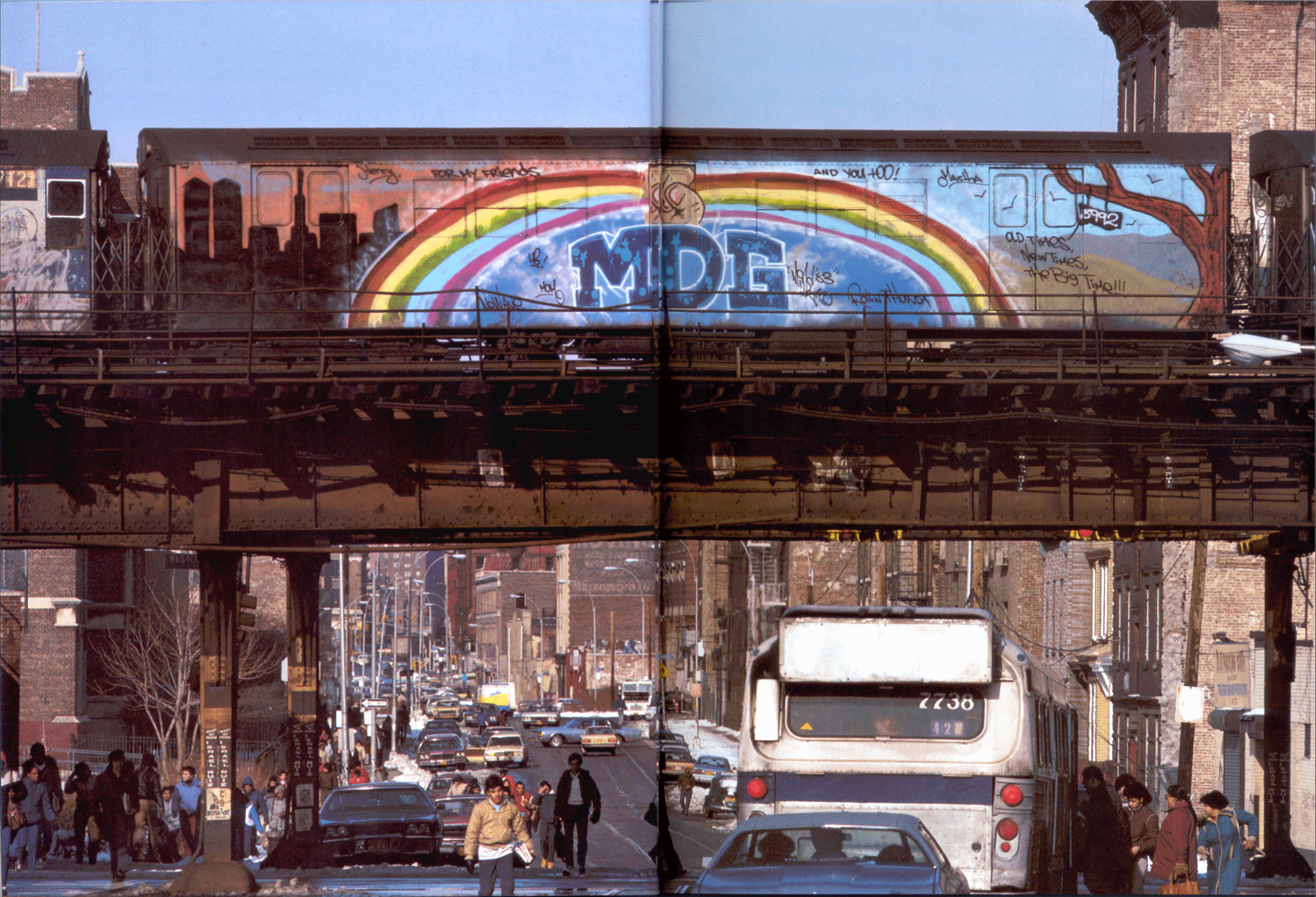

Capturing the painted trains against the backdrop of the city and seizing the imagination of the viewer, Cooper’s contribution shaped the way in which train graffiti could best be interpreted and understood. Although Cooper has always regretted being regarded by colleagues as a ‘graffiti photographer’ rather than simply as a photographer, her status within the graffiti scene is akin to that of a rockstar. Everywhere she travels, she is thanked profoundly by artists who tell her that Subway Art had changed their lives.

Subway Art came as the positive answer to a negative press and a tremendous antipathy to what was seen as a plague of graffiti. Along with the film Style Wars (1983) which Chalfant co-produced with Tony Silver, Subway Art in essence proved to be the saviour of graffiti, paving the way for that form of art to permeate society – from pop culture to advertising – and become the omnipresent phenomenon that everyone is now familiar with. The popularity of Subway Art has meant, however, that other, much lesser known forms of graffiti (that originated in other places in other countries) and other graffiti narratives are usually either absent or at best buried in what is often presented as the ‘official history’ of modern-day graffiti.

Inadvertently, Subway Art seems to have even obscured an interesting chapter in the history of graffiti that transpired in New York itself. One that directly preceded the spray painting adventures captured in Cooper and Chalfant’s visual anthropology. In the 1970s, a much darker, ‘heavy metal’ variant of aerosol art on subway trains incorporated cartoon characters and wasn’t focused on name writing. The most prominent graffiti artist of that generation – Caine 1 (Edward Glowaski) – is known for having painted the first whole train in graffiti history (‘The Freedom Train’, 1976) and for having had significant influence on various writers that succeeded him after his untimely death in 1982 at the age of 24. Subway Art features a tiny, tucked-away photo of Caine 1 spray painting a skull with a headdress, but that wasn’t the exposure others were lucky enough to get and by and large, his legacy has been condemned to oblivion. The likes of Crash, Daze, Futura, Lady Pink, Lee Quiñones, Seen, and Zephyr, to name but a few of the artists who were truly offered a priceless global platform through Subway Art, are more probable to ring a bell among the average graffiti enthusiast.

In light of this, it’s worth mentioning that at public events Cooper has often worn a jacket made by Caine 1 in order to keep his memory alive, while Chalfant in turn apologised in the 25th anniversary edition of Subway Art for the fact that ‘[…] many pioneering artists who were painting trains before we came along were left out. Marty and I would like to acknowledge all those great artists whom we missed due merely to circumstances of timing and location. We’re sorry!’

Bringing an ephemeral heritage back to life

Given its acclaim, Subway Art could be regarded as the epitome of intangible heritage within graffiti culture. The book itself is obviously tangible, but that doesn’t apply to the works it depicts, all of which are long gone. One way of exploring this seminal publication from this point of view, is paying heed to a particular graffiti project that is both the ultimate ode to it, as well as the most direct attempt to bring back to life an ephemeral heritage.

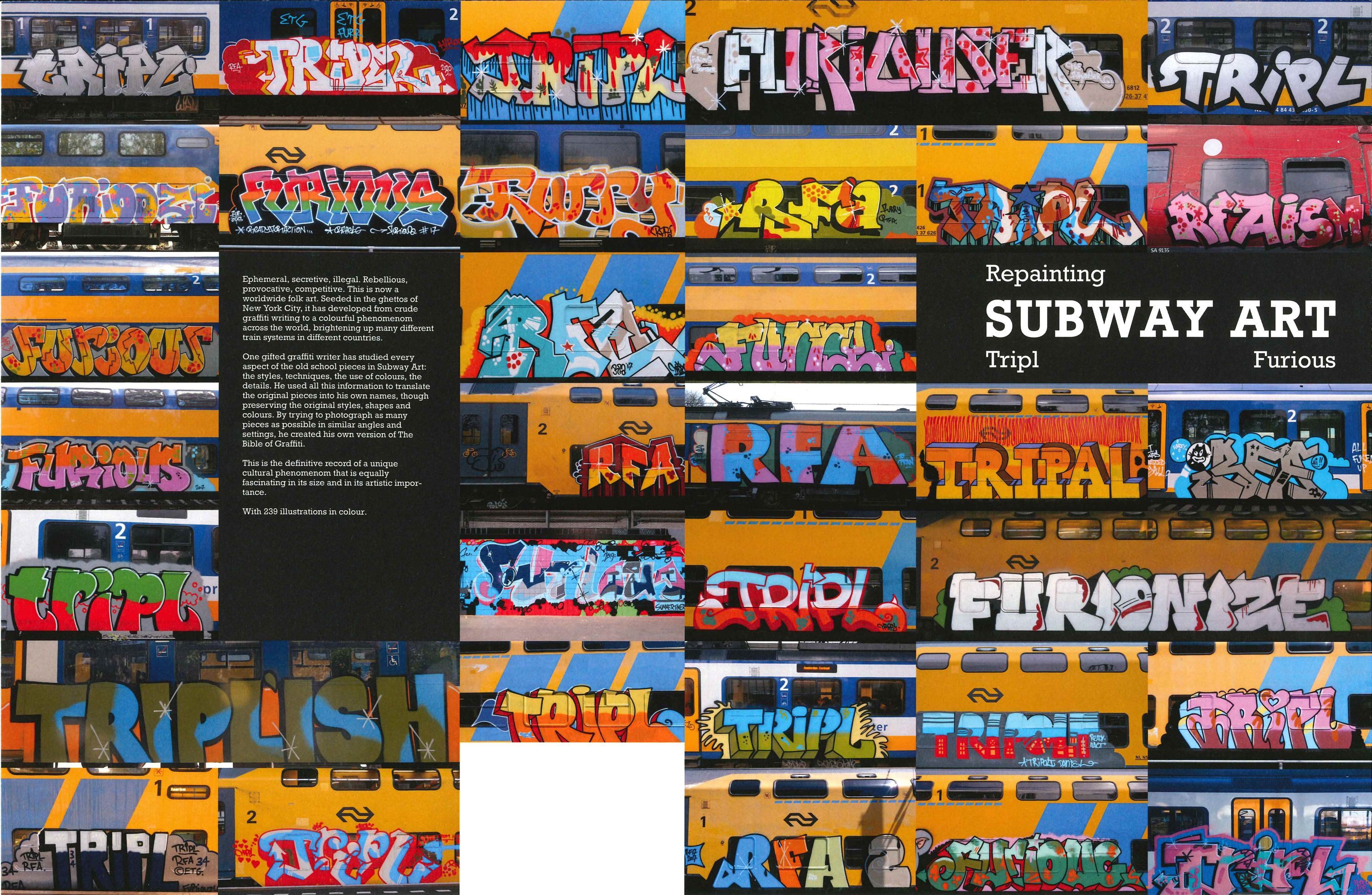

Over a ten-year period, a Dutch graffiti artist who goes by the names of both Tripl and Furious meticulously recreated on trains in the Netherlands all 239 individual works featured in Subway Art. In addition, he reenacted every scene from the book and made sure his own photographs of these works and scenes were as similar as possible to the original shots by Cooper and Chalfant.

Posing like a spray painting Dondi White jammed between two subway cars? Easy! Dressing up like those two moustachioed cops stood inside a subway car covered in tags? Sure thing. Playing on a wrecked train, hanging upside down from one of its open windows? No problem. Running towards the camera on top of a subway car donned in shorts and a green and white striped T-shirt just like the boy in that illustrious photo from 1980? You bet. Tripl/Furious did that too. Chilling out, sketching in black books, and drinking booze like Dondi is seen doing with his friends was a piece of cake by comparison, except finding precisely the right objects to recreate the blue room they were sitting in, wasn’t. That took Tripl/Furious forever and a day, but he succeeded eventually. No one can deny that his devotion to the cause was second to none.

And there is nothing ambiguous about the name Tripl/Furious gave to his mission. ‘Repainting Subway Art’ (RSA) is an unprecedented endeavour in terms of aspiration, scale, timespan, and attention to detail. Eager to learn all about it, Nuart Journal managed to catch up with Tripl/Furious (from here on called only Tripl for ease of reading).

What made him go to such great lengths and how did he actually pull it off? To shed more light on this project (which, remarkably, has had almost no coverage at all in any other media), we also sat down with Jasper van Es, curator of the travelling gallery show dedicated to RSA.

The point of no return

Coming from the skate scene originally, a friend introduced Tripl to the world of graffiti at the start of the noughties. It set him off spotting trains and creating his first tag as a teenager in 2001. ‘One year on, I did my first piece on a commuter train, all on my own. It was both a terrific and a terrifying experience’, he recounts his baptism of fire. ‘I remember how, suddenly, the engine of that train started roaring, and I stood there petrified in the yard. Thankfully, there was nothing amiss, it was just a common thing for that type of train to do every once in a while.’

Ever since, he’s been up on trains, initially writing only as Tripl. After a while however – when that name systematically appeared left, right and centre – he started running into trouble and switched to Furious. Several years thereafter, he deemed it safe enough to readopt Tripl, and had two aliases from that point onward.

It was around 2004 that Tripl got acquainted with Subway Art, albeit in somewhat peculiar fashion. ‘One particular day, a much older graffiti writer I knew had become completely fed up with spray painting after he got robbed while doing so. It seemed a rash decision, but that guy generously gave me all his spray cans and graffiti literature in one fell swoop. That included Subway Art, but it took me another decade or so before I really started studying that book’, explains Tripl, whose sources of inspiration were first and foremost two magazines he grew up with, i.e. the well-known Bomber Magazine and another one called Fuck Off.

Studying Subway Art is one thing, reproducing it from start to finish is quite another. What made Tripl decide to embark on such a huge and highly ambitious operation? Was it a long-held plan, a bet, or a joke that got out of hand? ‘It was the latter’, he says. ‘For Christmas 2013, along with some friends I decided to do a remake of the Happy Holiday piece by Seen – a whole car. A few months on, I was encouraged in jest to do a variant of the Hand of Doom [originally also by Seen], turning it into the Cock of Doom.’

‘Then nothing happened related to Subway Art for two years. I did the third remake in 2015, though only as a result of a lack of ideas. I didn’t know what to paint when a friend suggested recreating yet another work from the book. Subsequently, people started to challenge me to repaint all the works in it. While it all started off as a joke, things became increasingly serious at the start of 2017, at which point I got my head down and there was no turning back. Overall, it took me ten years to complete the entire undertaking, although I did eighty percent of the remakes between 2017 and 2021.’

This is iiiiiiit!

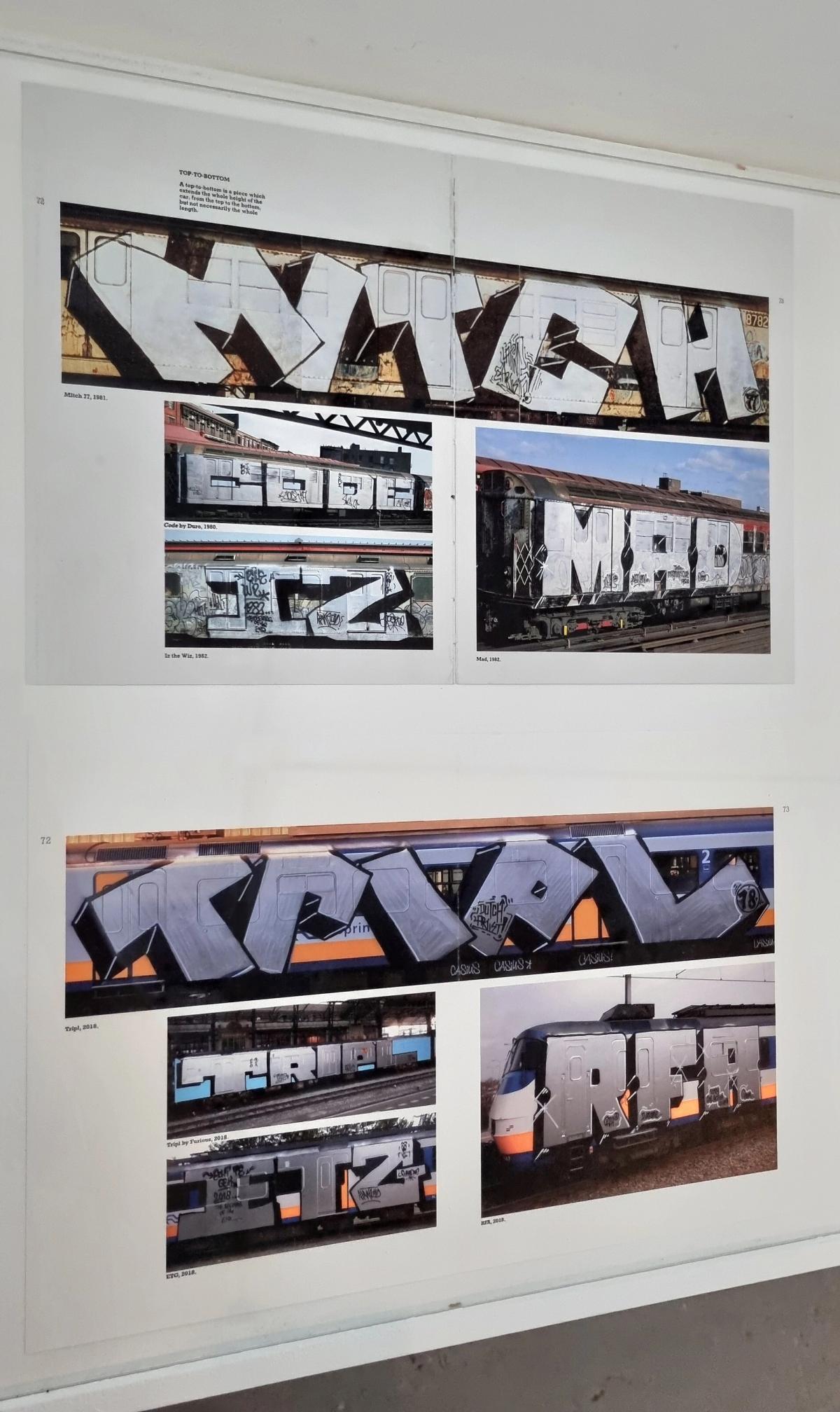

The remakes were highly similar in terms of image, style, and colour, though rarely identical to the original artworks. Tripl would, for example, routinely replace the names of the original writers with (variants of) one of his own, or with the names of two Amsterdam-based crews he’s a part of (ETG and RFA). Which moniker he would use depended mostly on (the length of) the names on the trains in Subway Art.

Doing graffiti was commonly called style writing at the time and, fittingly, the difficulty for Tripl – whose ‘own alphabet’ consists of very solid, readable letters – lay in convincingly copying a plethora of styles. ‘I could write my own name in my own style blindfolded, but to do so in another artist’s style is really quite different. You don’t adopt someone else’s way of writing just like that, it takes practising and adjusting skills’, he affirms.

In some instances, Tripl granted himself yet more artistic freedom, incorporating all sorts of differences, small and large, a lot of them tongue-in-cheek and sometimes referring to the present. The fact that the images and texts he sprayed on Dutch trains were often a direct response to images and texts on subway trains in New York over 40 years ago, is arguably one of the most intriguing aspects of RSA. Mimicking the past through time and physical space, he truly turned it into a conversation with (graffiti) history.

‘This is what graffiti art is not the other way around!!!!!’, Lee professed on a train in 1979. ‘This is iiiiiiit!’ replied Tripl in 2018, with a clear reference to that famous clip from Style Wars where a group of young writers in a state of elation see their own artistic achievements slowly slide by on a train. One of them can’t stop yelling ‘This is it!’. In 1980, Lee wondered in an epitaph on a train whether ‘[…] graffiti will ever last????????’. ‘Yes, it will!!!!!!!!’, answered Tripl decisively 38 years later with a matching number of exclamation marks.

The text ‘Dump Koch’ accompanied by the face of then New York mayor Ed Koch who introduced a zero-tolerance policy towards graffiti (Spike Lee, 1982), was swapped for ‘Dump Trump’ and Trump’s face (2018). A whole car by Lady Pink (1980) that paid tribute to ‘John Lennon’, metamorphosed into a whole car that instead read ‘Michael Martin’, paying homage to Iz the Wiz (2018 also). One other random example: the bespectacled man wearing a suit who is seen reading a newspaper on the subway through the opening of the soon closing graffitied doors was substituted for a woman in the exact same position, albeit looking at her smartphone – a sign of the times.

No lack of challenges

Overall, RSA required a great deal of organisation, dedication, and discipline. Tripl confides that while the project was a lot of fun, he did at times yearn for it to be over and he considered giving up more than once. He never did, but once he brought the job to an end, a huge burden fell off his shoulders. Although there were no outright setbacks along the way, there certainly wasn’t a lack of challenges – not least because RSA was by all means illegal from start to finish and working swiftly was imperative at all times.

At no time during the repainting of Subway Art did Tripl get arrested, despite the eternal cat-and-mouse game between graffiti writers and security personnel. The security measures implemented by the Dutch railway operator and railway infrastructure owner have probably become more, and certainly not less stringent throughout the period RSA was ongoing. They were in any case much more thorough and sophisticated than the few that were in place in 1970s and ‘80s New York. ‘Although I have my favourite train yard in Amsterdam which I know like the back of my hand, like all graffiti artists doing trains, circumventing security is very much a part of planning my every next step’, he emphasises.

As for the process of painting itself, there was no ironclad strategy and certainly no chronological way of proceeding. In other words, Tripl didn’t tackle the artworks from the book page by page. ‘I set out repainting the smaller, somewhat easier works first. The big ones were the most difficult – I dreaded doing some of those and tended to save them for last. Initially, the colours of the spray cans I had on hand at any given time made me select the works that still needed doing. At some point,

I purposefully started buying spray cans necessary to recreate certain pieces. All in all, I spent thousands of euros on thousands of cans and other materials.’

Preparation at home was paramount, he points out, ranging from selecting the right cans and putting them in the bags in the right order so as not to waste time in the yard looking for them, to making colour sketches of all the works to be used as examples in situ. ‘Making a sketch half an hour in advance was the best way for me to get in the groove once I found myself on the spot. One thing I had to keep in mind is that Dutch train carriages are twice the size of a New York subway car, so many remakes had to be much larger too.’

Then again, in the 1970s and ‘80s there weren’t nearly as many different spray can caps available as there are today. So unless writers increased the width of the paint stream by retrofitting the caps and thereby essentially creating their own fat caps avant la lettre (which a lot of them did), it would take a group of artists several more hours to colour a whole car than it would now take Tripl on his own. All the more so as the paint used at the time was far less opaque and pigmented, lacking the quality it has today.

This, however, also implied that a lot of the graffiti works from that early era were rather ‘painterly’ in nature (what art looks like is in large part dependent on the possibilities offered by the materials at hand). The spray cans and paint that Tripl has at his disposal are of superior quality (and manufactured to be able to create sleek lines), but, ironically, that’s precisely what made the production of his copies more difficult. Overall and by comparison, his works probably pop out a bit more.

That perfect shot

Tripl made it hard on himself by not only trying to reproduce the works of art, but also by attempting to take photographs of those works that majorly resemble the ones in Subway Art. In actual fact, he was never quite done without there being a proper picture taken from a similar angle and in similar settings. Illegal graffiti painter not being the average 9-to-5 job, Tripl usually worked at night, though not always. When he did work in the dark, he had to make sure by daylight that every work was photographed as soon as possible. Particularly so in the case of train carriages completely covered in paint as they’re the ones pulled out of service quickest in order to be buffed. This usually meant getting up very early after a night with only very few hours of sleep, or no sleep at all.

There were no guarantees, however, as Tripl could never be certain whether or not his nocturnal efforts had gone to waste. He indeed failed to capture his remakes on camera several times as a result of buffing. One specifically challenging remake required painting two consecutive whole cars originally painted by Duster and Lizzie (pictured in Subway Art from a high angle, with the train crossing the Bronx River at Whitlock Avenue). Tripl didn’t manage to finish the second car on time, meaning both of them had to be completely redone at a later date as the train was cleaned soon after his first attempt. Frustrating? No doubt, but inevitably part of the game, especially doing everything single-handedly.

‘I prefer to work on one particular side of the train to reduce the chance of getting caught’, he explains. ‘Sometimes, the remakes had to be made on the other side for the sake of being able to take a resemblant photo later on.’ But there is only so much you can do in terms of planning ahead. You may well end up in the unfortunate circumstance of being ready and well positioned to take that perfect shot, when – at the supreme moment – you suddenly run out of luck as another train crosses the one with your artwork, blocking it from view. This happened to Tripl on a number of occasions, and armed with a camera, he didn’t always get a second chance to redeem himself without resorting back to the spray can first.

As RSA progressed, Tripl began taking the photography more and more seriously, and he regrets having taken many photographs with a relatively poor camera during the first number of years of the project. The fact that he repainted several of his remakes at a later stage merely to be able to take a better picture with a quality camera, attests to his commitment to RSA.

Endorsement from Cooper and Chalfant

When asked, Tripl confirms that RSA represents the snow-capped summit of his graffiti career (which is far from over, he stresses). Countless people will have seen Tripl’s remakes, but would have failed to realise that these were part of a larger puzzle that was put together step by step over an extended period of time. Only fellow graffiti writers knew what he was up to. His friends knew from the start, others learnt about it soon enough through social media. His remakes were definitely recognised as such and the photos were shared online. ‘Most of the reactions to RSA were positive’, Tripl tells, ‘except for a few whiners who complained that I was copying other writers’ styles, but of course that wasn’t at all my goal in and of itself.’

Reassuringly, some of the graffiti writers from the ‘80s that are still around are supportive of RSA and have his back, like Kel, Quik, Seen, and Skeme (who, on a trip to the Netherlands in 2018, teamed up with Tripl to paint a train). No less important: Cooper and Chalfant also fully endorse the project. ‘They love it’, says Tripl, who paid a visit to Cooper in New York to discuss RSA with her, while Cooper was briefly involved with the reenactment of her own book when she made a trip through Europe in 2021. ‘Some of the photos were taken by Martha herself, including the one where I impersonate Dondi standing on the railway track in front of the doorway of a train, sorting out my spray cans on the train floor. The remake of the portrait of Henry at the end of Subway Art is Martha’s also.’

Book and exhibition

Tripl would often be asked by fellow-writers when his own version of Subway Art would finally come out. ‘Publishing Repainting Subway Art has been on my mind early on into the project and we’re now close to finally realising it as the book will be released at the end of this year’, he says.

Edward Birzin, who wrote his PhD thesis (Subway Art(efact)) on the growth of graffiti from child’s play to an original art in 1970s New York – has been tasked by the publisher with writing the introduction to Repainting Subway Art, and updating all texts from Subway Art that will be featured in it. Considering Birzin’s multi-year Subway Art History Project, this is no coincidence, as this project is remarkably similar to RSA, and in part happened earlier and concurrently, albeit legally on walls, not illegally on trains. It saw Birzin and some ten friends take the classic graffiti styles and pieces from Subway Art, but change the names to names of famous people and thinkers, as well as places, events and phrases from history on a few dozen buildings in New York. Starting out that project with the intention to do every masterpiece from Subway Art and make his own book just like Tripl, Birzin’s original plan changed as his reproductions led him to complete a PhD. Either way, in commenting on RSA, Birzin has an abundance of theory and practical experience to draw on.

‘Repainting Subway Art will contain all the Subway Art remakes presented in exactly the same layout, but it will be twice as thick because in addition, it will also feature a lot of behind-the-scenes images, and images of things that ended in failure’, Tripl continues. ‘I want to offer the book along with a copy of the original, so people can put both copies side by side, just like at the exhibition.’

As far as the exhibition is concerned, Tripl didn’t actually want there to be one as long as the book wasn’t out, but this is how things panned out nonetheless, courtesy of Jasper van Es, an expert on graffiti and a curator of several graffiti shows. Van Es immediately identified the potential of RSA and curated a show dedicated to it that was held first in Eindhoven in the Netherlands, and then moved on to Leicester in the UK, and Weil am Rhein in Germany.

‘The exhibition in Weil am Rhein is actually a group show and it also features works by Tripl that are unrelated to RSA’, Van Es notes. ‘This is important because before you know it, people reduce your artistry to that one project that gets you loads of attention, when in fact you have so much more to offer.’ This indeed applies to Tripl, who’s done much besides RSA and has had (group) shows before.

‘The best thing would be if the RSA exhibition could one day move on to New York’, Van Es continues with a smile. Curatorially, he kept things pretty basic, offering visitors to the show the opportunity to compare the remakes with the originals, which – along with some artefacts spread around the exhibition space – are shown in various sizes side by side on walls and panels. The exhibition is in conversation with the book.

Van Es points out that he’s ‘particularly interested in meta-graffiti, whereby pieces themselves are not the work, or at best only half the work. It’s about how an ephemeral work ultimately appears on a screen, or is given a new place or function – as an ingredient to a new dish, a new expression. The documentation, adaptation, or new expression is ultimately the real artwork as well as the heritage.’

According to Van Es, realising heritage in the best possible way as an artist calls for a conceptual way of thinking. ‘In practice, it’s about the innovative, pioneering acts required to create a work, and about being ingenious enough to raise your visibility. In the age of Instagram, this is becoming increasingly important and while certainly not all writers have a full understanding of this, more and more of them do. The likes of Taps and Moses, Utah and Ether, and the 1UP crew are in a league of their own when it comes to this.’

‘From this point of view, I think that Repainting Subway Art has been an instructive process to Tripl, who’s very context-oriented and has a natural talent ‘to look beyond’ a piece before it’s made. He’s always concerned with how his works will be ‘consumed’, whether along the railway tracks or online.’

Just keep doing it

Through RSA, Tripl regenerated a heritage that exists only in the form of photographs. All of his remakes were short-lived. Indeed, they were often much shorter lived than the original works. ‘In light of the ephemeral nature of graffiti and graffiti’s relationship to intangible heritage’, Van Es comments, ‘the project was a reincarnation of Subway Art in slow motion. Absolutely no one besides Tripl has experienced quite what Subway Art is about in all its facets. You can’t get any closer to it than by doing what he’s done. Coming that close is certainly not for everyone. Some graffiti crew in Germany could have probably succeeded too, but in order to do this all by yourself in the Netherlands, you have to be really clever. Tripl is well-organised and focused, and uniquely qualified to bring Repainting Subway Art to fruition.’

‘As for the best way to preserve heritage, in my view that’s simply to keep doing it – in this case, to keep spray painting’, Van Es underlines. ‘I know someone who plays a 200-year-old cello. That’s great, and much better than preserving that instrument inside a display case. Documentation obviously plays a crucial role too, because if it wasn’t for the documentation of New York graffiti which in turn led to the publication of Subway Art, it would have died out like some other forms of graffiti, and graffiti history would have looked very different as a result.’

Name writing forever?

Zooming out from RSA and taking a broader look at graffiti culture, one could critically contend that – partly as a result of the general fascination with Subway Art – graffiti writers tend to look backwards and cling to that dominant letter-based variant of graffiti, rather than look forward. Not that there’s necessarily a need for that, but it’s remarkable to see that although every writer has their own style and overarching styles vary to some extent from place to place, generally speaking the visual language of graffiti (wild style, if you will) has remained largely the same over the decades. With some notable exceptions (some artists exploring more abstract graffiti styles), graffiti – particularly on trains – has evolved relatively little over time. Against this background, one may wonder whether and to what extent Subway Art has been not only a blessing to graffiti, but also an obstacle to it moving forward.

That said, and with Subway Art now being around for 40 years, what can we expect from the future of graffiti? Where will we be in 20, 30, or another 40 years’ time? ‘In terms of imagery, it’s about sticking to the rules of the game and staying close to the roots and tradition of the culture. It will remain a practice that revolves around the shape of letters’, Van Es claims.

Tripl thinks likewise, and he expects the emphasis will continue to be on name writing. ‘There are no indications that we will deviate from that on a large scale. There are artists who do, but they’re a minority. I do think there will be less and less graffiti on trains, perhaps that may even disappear altogether as security measures continue to increase. Things are getting ever harder for writers these days and in terms of security, I worry about the role artificial intelligence might play in the near future.’

Speaking of which, Van Es perceives a trend whereby graffiti artists tend to change their strategies rather than their creative output. ‘It’s becoming increasingly common for writers to put a piece on a train, take photos of it, and then immediately destroy the work by painting over it in order to cover their tracks and reduce the chances of getting caught.’

Thankfully, that never happened to Tripl on any of his Repainting Subway Art excursions and the forthcoming book that stems from it is one to look forward to.

Repainting Subway Art Exhibition

MU, Eindhoven, the Netherlands, June 10 – August 27, 2023

Leicester Museum & Art Gallery, Leicester, UK, February 3 – May 27, 2024

Colab Gallery, Weil am Rhein – Friedlingen, Germany, June 10 – November 2, 2024

(part of a group show called ‘Patience.’)

Repainting Subway Art

Ruyzdael Publishing, Amsterdam

book forthcoming late 2024

ruyzdael-publishing.com

@whentriplgetsfurious @jaspervanes

- 1

Selina Miles’s 2019 documentary film Martha: A Picture Story is full of such scenes.

- 2

Subway Art also features the image of a ‘memorial car’ for Caine 1 by MIDG (‘Caine 1 Free for Eternity’).

- 3

Derived from ‘Caine 1, free for eternity’, a talk given by Dr. Edward Birzin at the Tag Conference in Linz, Austria (May 16–17, 2024). Birzin will dig into Caine 1’s story much deeper in the upcoming Repainting Subway Art book, of which he is one of the authors.

- 4

A point made by Edward Birzin on page 268 of his 2019 PhD thesis Subway Art(efact).

- 5

See ‘Graffiti of New York’s Past, Revived and Remade’ in The New York Times, October 26, 2010. [Online] Accessed July 31, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/27/arts/design/27graffiti.html?pagewanted=2&_r=0.

- 6

Commenting on RSA for this article, Dr. Birzin even draws a parallel with world literature, as he looks ‘at Tripl like a neo-Leopold Bloom’, the protagonist of James Joyce’s Ulysses. ‘Tripl took an Odyssey using Subway Art as his guiding light.’

Birzen, E. (2019) Subway Art(efact). PhD thesis. Free University of Berlin. Online: https://refubium.fu-berlin.de/handle/fub188/26288?show=full.