Abstract

Through a series of examples, this essay explores the way in which artists’ documentation of their actions in urban space has contributed to the development of what I term action-documentary practices – or actumentary. These practices are transformative in that urban intervention becomes a tool for documentary and experimental writing. I argue that action-documentary is formed in the reciprocal relationship that exists between urban action and its capture. This facilitates two levels of reception: the first where the urban action operates as a work of art in the real world, and the second where the documentation of the original action is no longer simply at the service of the action, but ultimately becomes an action in its own right that serves as an autonomous, supplemental narrative device. Through its viewing as action-documentary, the action documented can gain a certain intensity and replicate the effected experience in a different way.

Urban intervention in the post-media era

At the turn of the millennium, the democratisation of digital tools and the internet allowed for the development of open source amateur and professional practices and resources driven by the value of the freedom of information. However, this democratic open-access dynamic was undermined in the early 2010s, with the advent of social media and the growing control of online spaces by GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft). In 1989, the philosopher Félix Guattari forecasted this period as a post-media era, arguing for a reversal of ‘mass-media power’ by the reappropriation of ‘machines of information, communication, intelligence, art, and culture’. Many artists working today are consciously part of the reappropriation that characterises this post-media era.

The artistic practices of urban intervention which developed at the beginning of the 2000s benefited from the development of accessible photographic and video-documentation devices and editing tools, and increasingly light, mobile, and fluid methods of dissemination. Until the shift of web culture towards ubiquitous, instantaneous, and proprietary use linked to smartphones and social media platforms, access to street art via documented action catalysed its popularity, since its in situ experience was then complex to post-produce. Beyond the spectacular wave of neo-muralism, the increased popularity of street art was courtesy of the dissemination by artists of photos and videos of their own creative processes on personal websites, blogs, and image-based online platforms.

From documented action to action-documentary

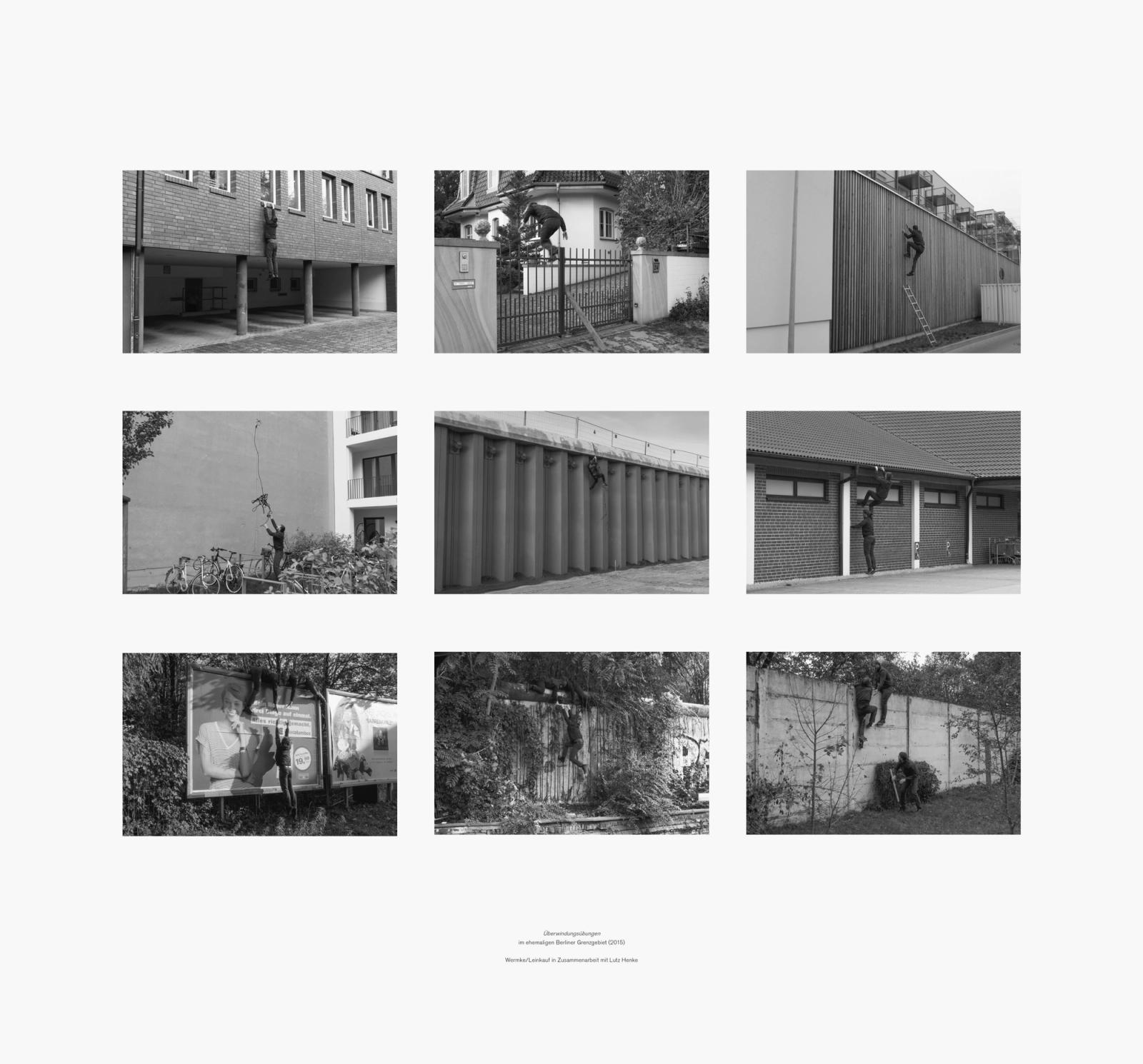

In 2015, Matthias Wermke and Mischa Leinkauf created a series of actions entitled Überwindungsübungen (surmounting exercises, Figure 1) in collaboration with Lutz Henke. Having recovered archival footage from 1974–1975 showing East German soldiers simulating the crossing of the Berlin Wall, the artists transpose these exercises to the current environment along the former border that separated East and West Berlin. Most of the Berlin Wall was destroyed in 1989, but by playing with its absence and appealing to the memory of the body, they relocate the concept of an impossible border crossing to the landscape of residential buildings erected where the Iron Curtain once was. With the end of the Cold War and the globalisation of urban planning models, the only frontier now crossed in Berlin is that of the progressive enclosure of public spaces with the gradual domination of private residential neighbourhoods – carried over from the American model of gated communities – which produce a new separation, both social and capitalist.

In 2019, American artist Brad Downey, who lives in Berlin, asked French artist Julien Fargetton to take on the role of a street performer for a day (Figure 2). Disguised as a mime, Fargetton walks along the demarcation line of the old separation wall, moving his hands flat in the air and pretending to scan its surface for a breach. The pair cross the city centre to the very edge of the line’s materialisation on the ground, until it disappears beneath the new buildings – the same buildings climbed by Wermke and Leinkauf.

Here, capture is also part of the action, as Downey, camera in hand riveted on the mime, passes as a tourist in the midst of the crowd of tourists who have come to ‘see’ the old demarcation line, despite the fact that this is now an invisible border.

Together, these artists adopt a performative documentary style, in which history is told through a symbolic rematerialisation that takes place through the body. They address the difficulty of grasping a memory without the indiscriminate presence of artefacts in everyday life, since time, reconstruction, and urban planning through gentrification, district after district, has homogenised the city from west to east.

The archiving and displaying system adopted by the German duo, Matthias Wermke and Mischa Leinkhauf, plays with the archaeology of the media: on the one hand, the original documents are exhibited as a reference and didactic source for their work; on the other, the installation in the Maxim Gorki Theatre in Berlin featuring six carousel projectors in a row which loop the slide images of the artists, trying to cross residential barriers. The deafening noise of the carousels lends a certain gravity to the installation.

In contrast, the video by American artist Downey is in the tradition of performance recordings. It consists of a long video capturing – on either side of the old line drawn by the wall – the same person crossing the space with a slow, confident gesture that lends a certain anachronistic burlesque to the situation.

Documenting urban actions

In the field of street art, urban actions are often documented on video in a sequence shot in the tradition of 1960s performance filming. The duration of the shot underlines the labour of the body at work transforming the urban landscape. But it also quickly becomes a source of boredom, because it re-enacts the time-lapse of reality by embodying a point of view that replicates that of the static, curious passer-by, observing from a distance of around one and a half metres. There is no certainty over how such documentation is received by a certain audience.

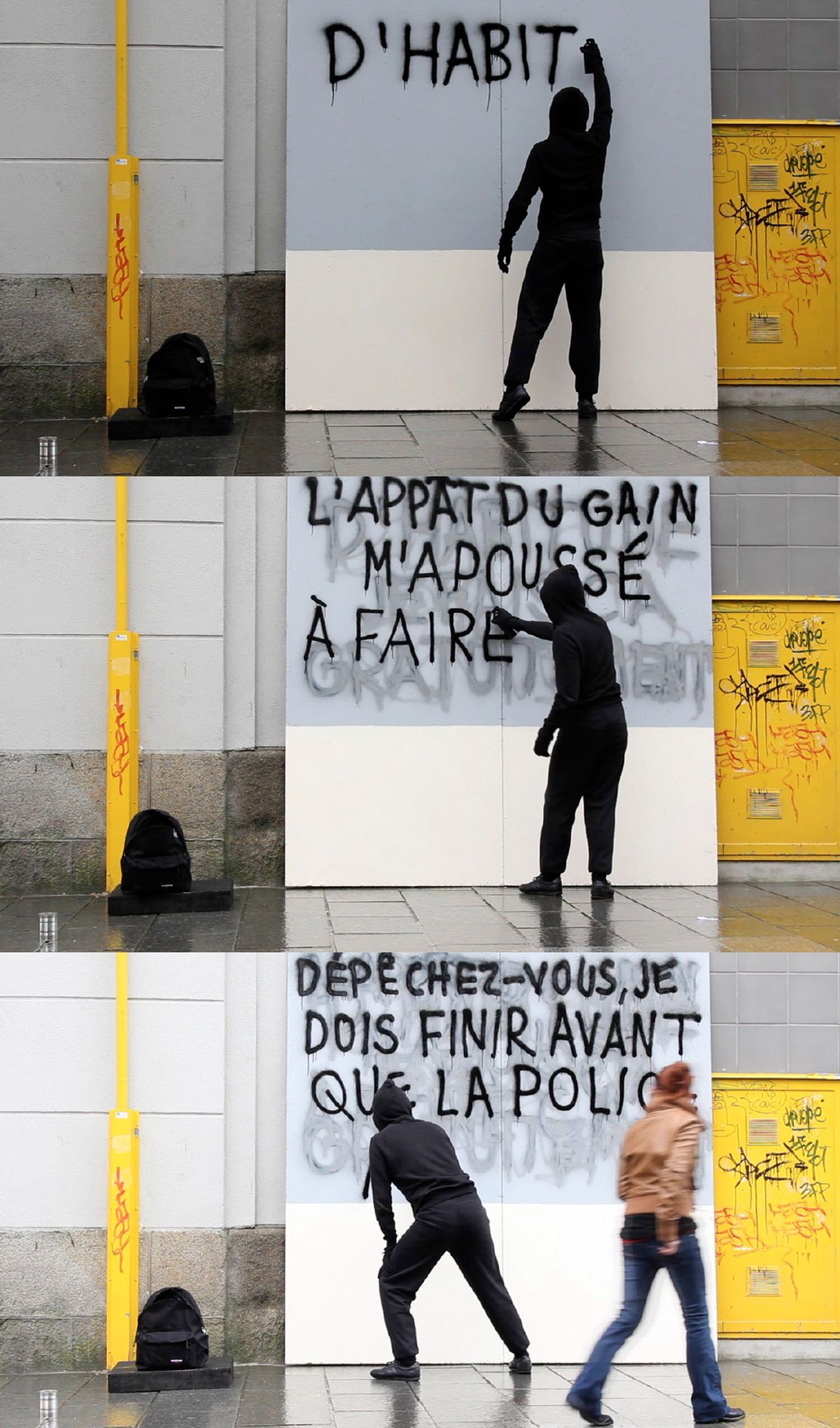

My ‘Graffiti Statue’ project (Figure 3) is a clear example of this, since its documentation, like its production, is based on spectacular expectations which are not met. In a shopping street in the centre of Quimper, France, I’m a street performer enacting a statue, dressed entirely in black, wearing a hoodie, jogging bottoms, and trainers.

When someone throws a coin into the metal box at my feet, I come to life for a few seconds and slowly spray paint a few words. After a few coins, I compose the following sentences in succession: ‘USUALLY I DO THIS FOR FREE’, ‘MONEY MADE ME DO IT’, ‘HURRY UP GUYS I HAVE TO FINISH BEFORE COPS ARRIVE’, and then improvisationally ‘MONEY MONEY MONEY MUST BE FUNNY’. The wall behind the writer-statue that I enact is covered with a picture rail of the same proportion and colour as the wall, so that an assistant can easily repaint it between two sessions. The action lasts two hours, while its documentation consists of a series of seven real-time videos of the seven slogans being painted. Each video lasts between five and ten minutes, depending on the slogan. The stillness of my frozen ‘statue’ stance between painting words creates a certain dramaturgy, but quickly wearies those who watch it online where the videos were shared. Graffiti Statue is intended to be read in the first degree as well as the second: as a classic street performance of a statue with no artistic intention, except that it is deceptive because the performer interacts with the audience as little as possible. The games of seduction that usually attract the audience are here reduced to the act of writing itself; the spectacle of the writer who embraces the simulacrum of subversion to curry favour with the art market. In contrast with graffiti, street performance is socially accepted because it is legal and declared as such.

This practice of documentation operates pragmatically and sometimes takes on a performative dimension as the temporary group occupation of public space re-enacts a simulacrum of legitimacy. In February 2012, during the urban creation residency in Quimper in the context of which I created Graffiti Statue, we came together as groups several times, with between six and ten people taking part in each action (Figure 4).

At each event, artist and artistic director Éric Le Vergé acted as mediator for the curious, while Didier Thibault took on the role of stage manager, assisted where necessary by Ronan Chenebault and Bénédicte Hummel, two art school trainees. Meanwhile, Erwan Babin and Florian Stéphan, two documentary filmmakers from Torpen Production, assisted by their trainees, set up and moved their professional video recording equipment, taking care to leave areas for passers-by to pass through or stop to observe the filming.

As the philosopher Alain Milon (2004) points out in relation to tagging, the practice of urban art, i.e. bodies in action, creates a spontaneous theatricality that transforms architecture from a setting into a scenic space. This is amplified here by the ostentatious presence of the tripod-mounted camera turned towards the site of the urban intervention and filming in public space, which reinforces the idea of transposing the fourth wall that delimits the stage from the orchestra pit and the rest of the theatre to the location of the lens that frames and documents the action.

Documented action such as this effectively becomes an ‘action-documentary’ or ‘actumentary’. This action-documentary is comparable to the register of the ‘mockumentary’. This portmanteau of mock and documentary refers to the practice whereby the director announces that they are going to make their film in a documentary fashion, but stages certain facts in order to weave the narrative thread of the documentary. The mockumentary, which has now moved into the realm of fiction, can be a tool of parody, satire, or social criticism. By virtue of the predominant place it occupies, filming itself, at the time of its production, organises the gesture into a shot rather than a sequence – ‘you have to make it for the camera’, as artist Akay once put it (Les Frères Ripoulain, 2011). The operator, who was supposed to capture the situation on the sly or in a sequence, stepping back in the tradition of reporter-photographers, instead here intervenes to propose their cut, or stopping or repeating the action, which in turn becomes the film shoot.

Video-performance

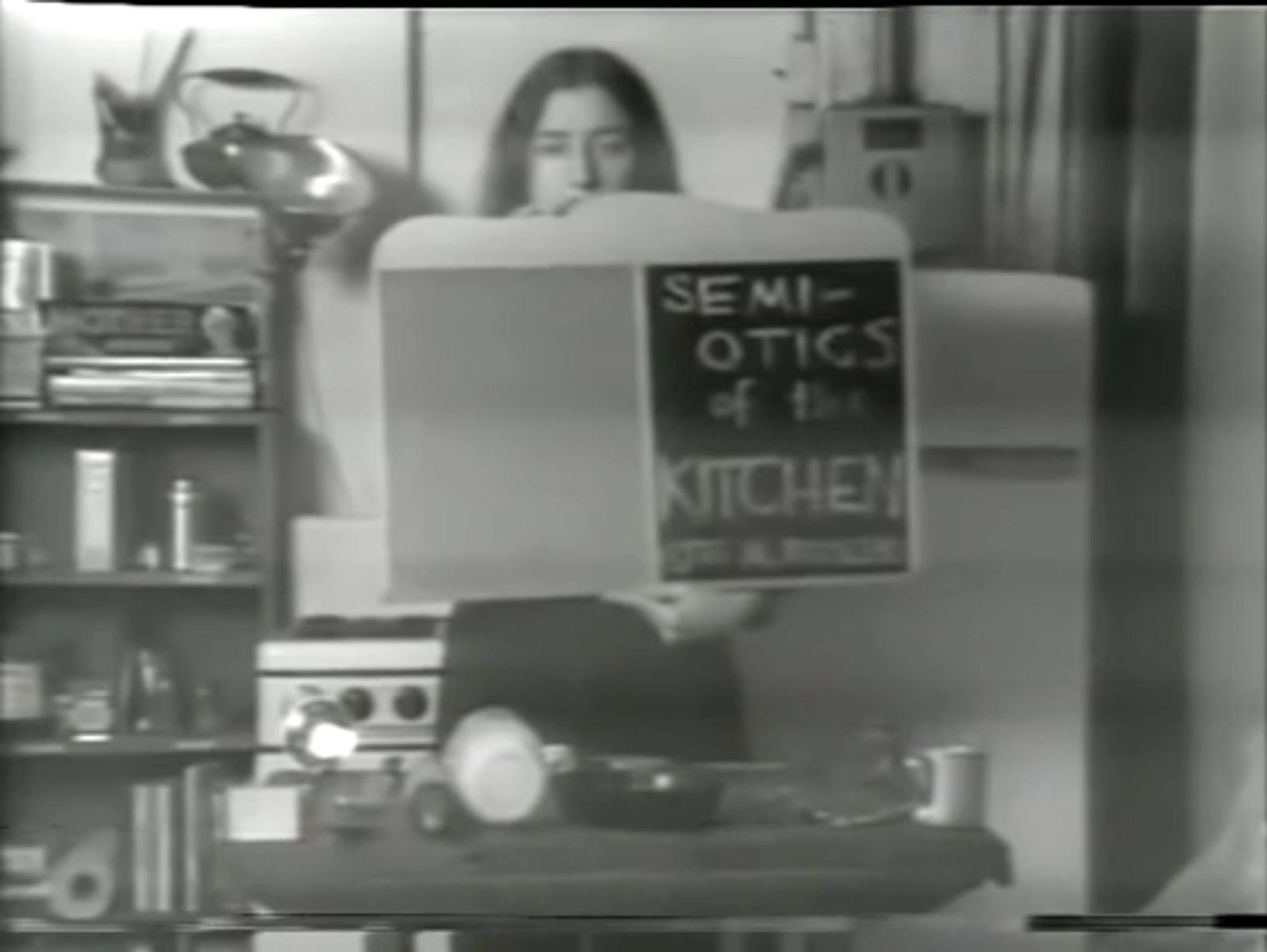

This concept of the action-documentary is distinct from video-performance, in which the artist uses the video medium in place of an audience and performs for the camera. The American Bruce Nauman introduced this practice in 1968 when he filmed himself in his studio walking exaggeratedly around a square traced on the floor (Figure 5).

Acknowledging that performance is always aimed at an audience (whether informed or not), Nauman took the shortcut of transposing and concentrating the audience’s gaze into that of the camera lens – thereby bringing about a transformation in his performative practice. From then on, it was no longer just the framework of his studio that set the limits of his performance space, but also that of the recording device. This principle was later taken up by the feminist art movement of the 1970s to question the condition of women and the multiple roles assigned to them by their gender. The American artist Martha Rosler, for example, produced the performance ‘Semiotics of the Kitchen’ (Figure 6), in which she parodied the figure of the housewife – an archetype popularised by television cookery programmes in the 1960s – by performing non-utilitarian reiterations of mechanical gestures in the very space of domestic alienation.

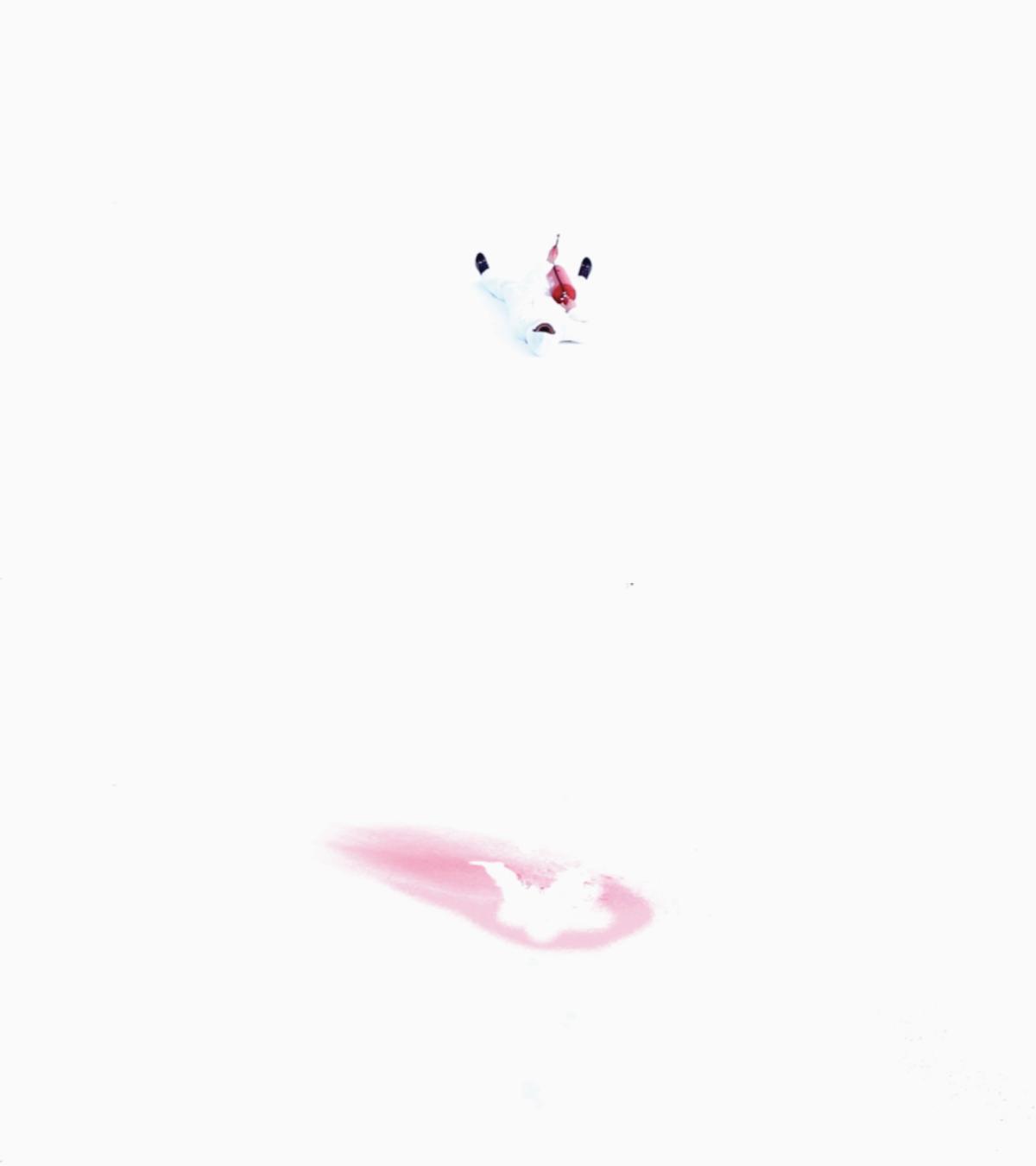

Video-performance also finds a place in urban art, with a number of solitary, isolated gestures filmed in the hidden camera mode that Vladimír Turner has made his speciality, making a mockery of the romantic figure of the artist. In an untitled performance (Figure 7), he enters the field of the immaculate white camera and advances to the centre of the image with a red fire extinguisher in his hand, also wearing a full-body white suit. He lies down on his back in the snow and sprays the red paint into the air, which falls back onto his body. When he stands up again, the silhouette of his body is outlined, and he walks away from the frame.

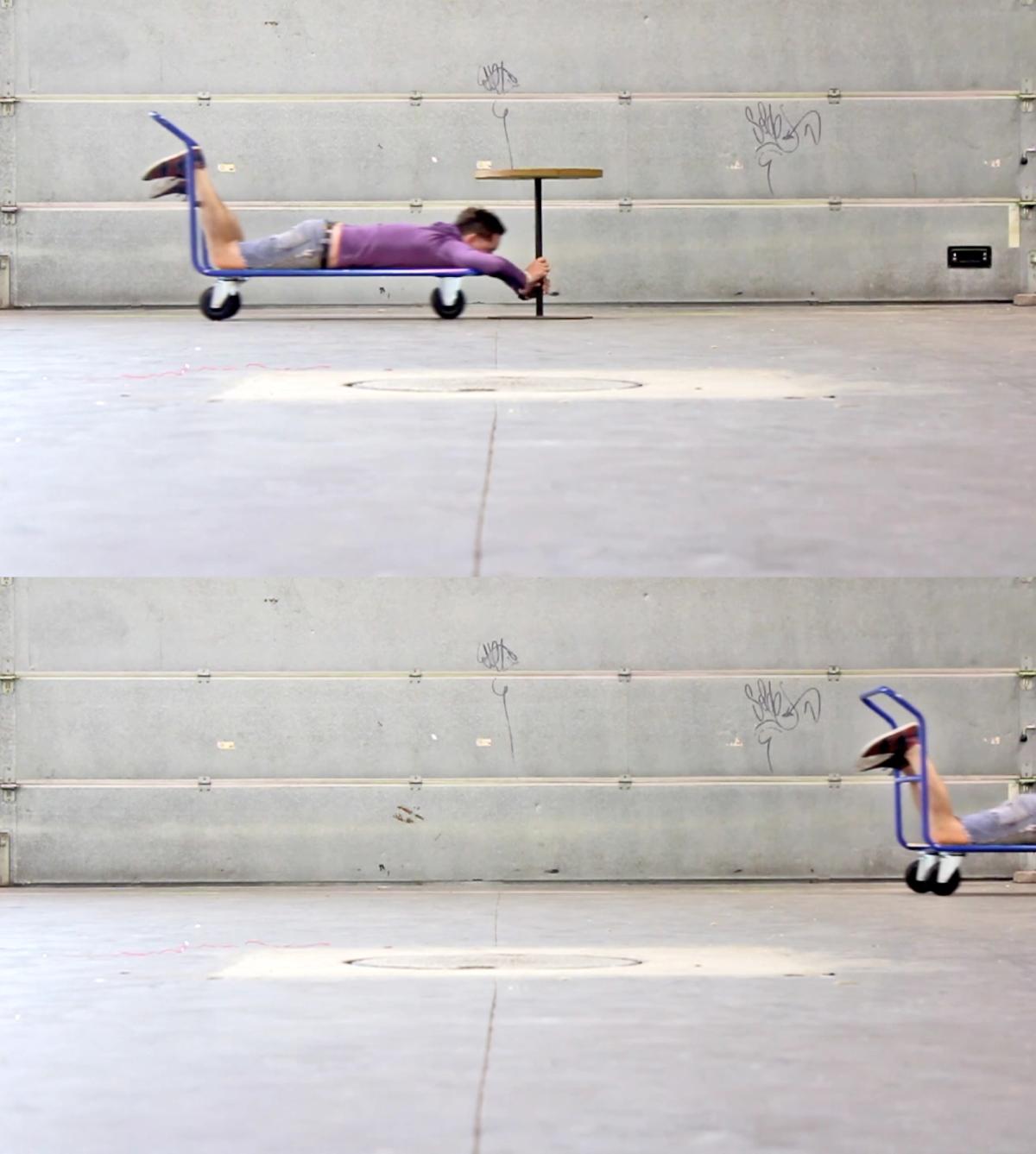

In ‘Sisysfos’ (Figure 8), Turner moves through a hangar lying on his stomach on a wheeled trolley, using a bar table to pull himself along. The performance seems to last an eternity; he has modified and lengthened the soundtrack to give an impression of disproportionate space.

The performative situation

As illustrated by these examples, the main difference between action-documentary and video-performance is that video-performance ignores the context and time of the situation by creating a single, non-human point of view to which the action is subject.

By contrast, the raison d’être of the action-documentary can be illuminated by the ‘performative situation’. A performative situation, as defined by the artist duo Vincent + Feria in conversation with art critic and curator Julia Hountou, is:

…a constant back-and-forth between different designations, but generically we can talk about performance. I tend to use the term lecture-performance, or performative situation, which I really like. We had previously developed and experimented with the notion of an ‘evolving device’. In performance, the action focuses on the artist, who often becomes an ‘actor’ in a spectacular space. The situation calls for interaction. We try to use this form in relation to our preoccupations; it allows us to formulate, to present questions and we translate it into this act of presence. We are not in the business of representation.

(Vincent + Feria, 2010: 35–36)

Understood in the 1960s as the encounter between the situation – as defined by the members of the Situationist International – and the performance, the performative situation aims to escape the ‘spectacle’ of performance and to introduce a sense of letting go, fluidity, and blurred contours: we no longer know where the performative situation ends and begins. This uncertain state makes it possible to go beyond the separation between artists and spectators, since, as a situation, space-time becomes a form of spontaneous theatricality in which all those present are actors, whether they want to be or not. Any concomitant action by a third party is welcomed and organically linked to what is being played out. This idea of a performative situation is similar to Allan Kaprow’s concept of the happening. Happenings are literally about welcoming ‘what happens’ at any given moment (1959: 4–24). On another level, they are also about intervening artistically in an environment, situation, or space in order to modify its content, while accepting and integrating the hazards that arise – which gives it a new dramaturgy that the artist underlined when he first proposed a definition in the 1950s.

During and at the end of each performative situation, Vincent + Feria produce documents: photographs, videos, and texts. These documents can later give rise to a protean account of the experience, which rearranges this fragmentary, indexical base to shed new light on the situation, with a bias closer to a visual essay than a documentary work. But with so much material accumulating after the experience, they found that they were running out of time for editing and post-production. While the duo conceives and implements performative situations in announced settings (conferences, vernissages, exhibitions, workshops, biennials) that ensure the intelligibility of the artistic context, the action-documentary is instead organised around the creative process of urban work in everyday life. As the documentation has been anticipated as a second reading of the urban action, it is often produced by a third party, which represents an issue in itself, in taking advantage of all of the involuntary performativity that is consubstantial with the situation created by the action itself.

Exemplars of the action-documentary form

The action-documentary lies in this reciprocal relationship between an actual urban action and its capture. This allows for two levels of reception: one where the action itself is a work of art in the real world, and the other where the documentation is no longer simply at the service of the action, but becomes an additional narrative tool. The documented action can gain a certain intensity and replicate the effected experience in a different way through its viewing. This is borne out by the following examples of artists who are experimenting with the documentary form and who are, in my view, exemplars of the action-documentary form.

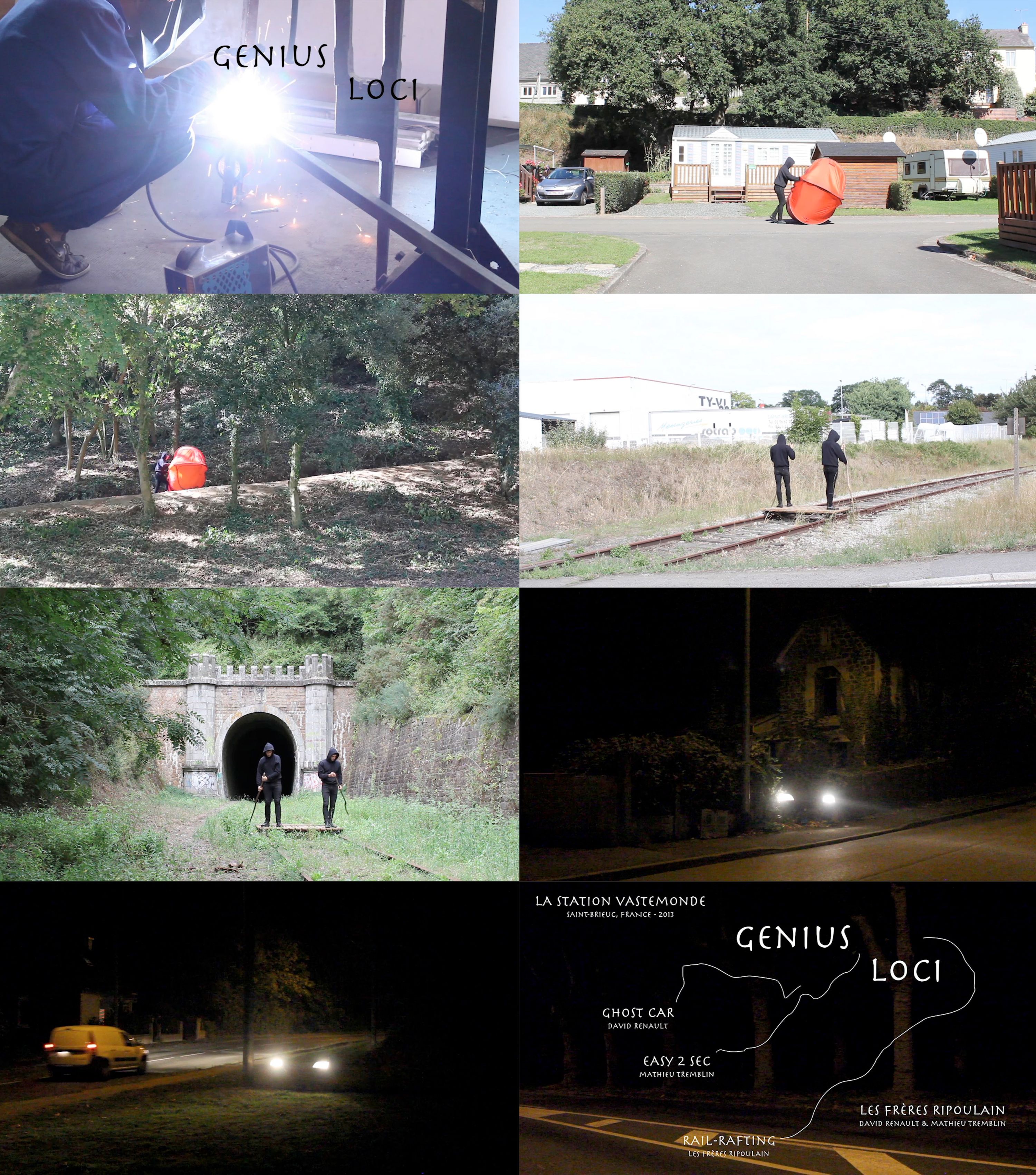

In ‘Genius Loci’ (Figure 9), produced in 2013 as part of an urban creation residency with Station Vastemonde in Saint-Brieuc, we chose to focus on the production of a series of artistic gestures in the city consisting of three constrained strolls along three routes through the Brioche landscape. Each action took place over several days and was repeated several times, so that virtually all of it could be documented in real time. Rail-rafting was the first action and we used a draisine on which a raft was fixed to travel the four kilometres of disused railway line linking the Beaufeuillage business park to the port of Le Légué, crossing various urban areas – industrial, educational, residential, leisure, and agricultural – and skirting the coastline. Our assistant Vincent Tanguy made the journey nine times, documenting it over a two-week period. He also extended the journey through the area, which took just thirty-five minutes each time we used the tracks.

‘Easy 2 Sec’ is a symbolic transposition of the myth of Sisyphus into a suburban environment. Over the course of a day, I crossed the four kilometres of valley in the heart of Saint-Brieuc – between Les Vallées campsite and the harbour in Le Légué – pushing ahead of me an ovoid structure on a human scale. This sphere was constructed from single-person folding tents, built one inside the other. This action re-enacts, in the field of consumer society, the punishment of Sisyphus, condemned for having dared to defy the gods by eternally rolling a boulder up a hill and rolling it back down again each time before reaching the top. This action, repeated twice, appears as an allegory of the condition of the nomad in the city – whether tourist or homeless.

Finally, ‘Ghost Car’ was a nocturnal stroll in which David Renault used a car lighting system to simulate the ghostly presence of a stationary car. Parked in a number of unlikely urban niches or on the side of the road for two evenings, the Ghost Car generated a fleeting and silent ghostly presence, like a disquieting mechanical sentry. Bringing together these three strands, Genius Loci takes a contemplative, melancholy look at Saint-Brieuc, a dormitory town haunted by its industrial and seaport past in decline.

In a similar poetic engagement with the environment, in 2016, Vladimír Turner directed ‘Funeral’ (Figure 10) in which he initiated a symbolic dialogue with an industrial landscape of coal mines, unfolding like a pagan ode to the Anthropocene. In front of the camera, Turner ‘partly improvises scenes and invents installations and performances with the allure of post-industrial land art.’ He plays not only his own role as an artist, but also that of an allegorical figure caught up in ‘a kind of imaginary funeral celebration for the dusty place and for this cursed landscape of the Ore Mountains’. He set out to create an eco-activist film, but it evolved into something much more experimental as the actions and recordings progressed: ‘a surreal collage of scenes and ambivalent tableaux vivants inhabited by an affective and critical vision of the way we treat the landscape’ (Turner, 2016: n.p.).

On a trip to Slovenia in the summer of 2018, American artist Brad Downey discovered that Melania Trump, then first lady of the United States, was born in the small Slovenian village of Rožno. There he met Maxi, a local who claimed he was born on the same day and in the same hospital as her. When Downey returned the following summer, he suggested to Maxi, a folk artist, that he create a one-scale chainsaw sculpture of Melania from a poplar tree on a nearby plot of land that he had bought.

As Downey follows the creative process, the focus shifts from the sculpture to Maxi, becoming a portrait of this singular figure and his relationship to the world. The anecdotal nature of Downey’s approach to the sculpture becomes a kind of symbolic conversation with the persona of Melania Trump – with the whole liberticidal imaginary of the policies being pursued by her husband, then US President Donald Trump, in the background. In July 2019, Downey published his documentary online (Figure 11). Immediately, the sculptor’s clumsiness was mocked in memes. The sculptural portrait, naive and crude, was used by detractors of Trump to mock him.

A second phase of documentation began around the reception and parodic appropriation on the web of Downey’s work produced in collaboration with the Slovenian sculptor. Exactly one year after the inauguration of this ‘monument’ to Melania Trump, the sculpture was set on fire by an anonymous arsonist on July 4, 2020. Given the political context, Downey had prepared a cast of the sculpture in anticipation, and a few months later, he replaced it with a bronze version. At the end of 2020, he made a second part of the documentary (Figure 12), this time focusing on the online reception of the statue, mixing videos of YouTubers expounding their conspiracy theories with news channels reporting on the reception of Melania Trump’s ‘monument’ as a new tourist attraction, or even a place of pilgrimage. Here, the narrative has effectively escaped its creator, who is now apparently merely a witness to the most unexpected developments.

Both Downey and Wermke and Leinkauf draw their action towards the documentary – as actumentary – not from the original narrative of the action, but from its reception, which is an integral component of this re-reading of the ‘artistic event’.

Similarly, Turner had already deliberately experimented with this principle. Since the mid-2000s, the anonymous Czech guerrilla art collective Ztohoven has been known for its virulent criticism of political corruption and the mass media. On June 17, 2007, its members hacked into the national television channel ČT2 and broadcasted live on the morning news a nuclear explosion in the middle of the Krkonoše mountain landscape. Their proposal, entitled Media Reality, is like an updated version of Orson Welles’ 1938 radio hoax ‘War of the Worlds’. As with Welles, the aim of their diversion was not to frighten the public – it was obvious to viewers watching that the explosion was fake – but to highlight the media manipulation at work. Their plan worked perfectly, and within a few weeks the artists found themselves at the heart of a colossal police and surveillance operation, being charged with terrorism.

Turner, who was secretly a member of the group at the time, decided to do his final year project on the reception of this action at the film school in Prague where he was studying. In 2008, he produced ‘On Media Reality’ (Figure 13), a documentary film in which he first follows the art collective in action, and consequently shows the response by the media and incredulous onlookers, the detectives in charge of the investigation, the National Gallery presenting Ztohoven with an award, and the terrorism trial. He details a profusion of points of view, using his student hat to be both judge and party to the action.

Conclusion

This essay has considered the ways in which artists’ documentation of their urban actions have contributed to the development of what I term action-documentary – or actumentary – practices. As the examples above illustrate, this is transformative in that urban interven-tion has become a catalytic tool for documentary and experimental work. In contrast to conventional video-performance, in which the artist uses the video in place of an audience and performs for the camera, the action-documentary is formed in the reciprocal relationship between an urban intervention and its capture. This allows for two levels of reception: one where the urban action itself is a work of art that is produced in the real world, and the other where the documentation of the action is no longer simply at the service of the action, but rather becomes an additional – and sometimes unpredictable – narrative device in the post-media era.

Mathieu Tremblin (1980) is a French artist-researcher and associate professor in Visual Arts in the School of Architecture of Strasbourg (ENSAS), France. He lives in Strasbourg and works in Europe and beyond. Tremblin is inspired by anonymous, autonomous, and spontaneous practices and expressions in urban space. He uses creative processes and simple, playful actions to question systems of legislation, representation, and symbolisation in the city.

He is also developing a practice-based research linking urban intervention, urbanities, and globalisation. It takes the form of editorial direction, exhibition curation, or collaborative proposals and has resulted in initiatives and projects such as Éditions Carton-pâte, Paper Tigers Collection, Office de la créativité, Post-Posters, Anarcadémisme, the documentary collection of the Amicale du Hibou-Spectateur, Die Gesellschaft der Stadtwanderer.

Tremblin’s research focuses on the relationship between the right to the city and artistic urban practices, as well as on sensible diagnosis as a tool for citizen empowerment, processes of co-creation and self-dissemination in relation to social struggles, and the permeability of uses between digital and urban spaces.

- 1

A human-powered light auxiliary rail vehicle used to transport materials for railway maintenance.

Downey, B. (2019) The Ground Walks With Time in a Box. Full HD video, colour, sound, 16:9. 18 min 59 s.

Downey, B. (2019) Melania. Full HD video, colour, sound, 16:9. 12 min 11 s. [Online] Accessed August 20, 2024: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=5tY62-dSx40&t=16s.

Downey, B. (2020) Melania. Full HD video, colour, sound, 16:9. 8 min 11 s. [Online] Accessed August 20, 2024: https://vimeo.com/501813677.

Guattari, F. (1989) The Three Ecologies. London: Continuum.

Kaprow, A. (1959) ‘The Demiurge’. Anthologist, 30(4).

Les Frères Ripoulain (2011), ‘Le graffiti comme carte psychogéographique’. Graff It, 36: 66–73 (proceedings of the seminar ‘Graffiti as Psychogeographical Map: The New European Urban Intervention’ (directed by Abarca, J.), August 22-26, 2011, Menéndez Palayo International University, Santander Spain).

Les Frères Ripoulain (2012) Urban creation residency ‘1 + 1 = 1 1 + 1 = 2. 2011–2012’. Pôle Max Jacob, Quimper, France – curation: ART4CONTEXT. [Online] Accessed August 20, 2024: http://art4context-residence-ripoulain.over-blog.org.

Les Frères Ripoulain (2013) Genius Loci. Full HD video, colour, sound, 16:9. 21 min 18 s. [Online] Accessed August 20, 2024: https://vimeo.com/videos/244805602.

Milon, A. (2004) ‘Les expressions graffitiques, peau ou cicatrice de la ville?’ in: Civilise, A-M. (dir.) Patrimoine, tags & graffs dans la ville: Actes des rencontres Renaissance des cités d’Europe. Bordeaux: CRDP d’Aquitaine, 2004: 122-138.

Nauman, B. (1968) Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square. 16mm film transferred to video, black and white, silent, 4:3. 10 min. [Online] Accessed August 20, 2024: https://www.moma.org/collection/works/117947.

Rosler, M. (1975) Semiotics of the Kitchen. Video, black and white, sound, 4:3. 6 min. 09 s. [Online] Accessed August 20, 2024: http://www.moma.org/collection/works/88937.

Tremblin, M. (2012) Graffiti Statue. Full HD video, colour, sound, 16:9. 10 min 06 s, 6 min 01 s; 9 min 15 s. [Online] Accessed August 20, 2024: http://www.demodetouslesjours.eu/graffiti-statue/.

Turner, V. (2008) On Media Reality. Full HD video, colour, sound, 4:3. 44 min 20 s. [Online] Accessed August 20, 2024: http://sgnlr.com/works/on-screen/on-media-reality-2008-prague/.

Turner, V. (2011) Untitled (Red). Full HD video, colour, sound, 16:9. 2 min 13 s. [Online] Accessed August 20, 2024: http://sgnlr.com/works/on-screen/untitledred-2011-prague/.

Turner, V. (2011) Sisyfos. Full HD video, colour, sound, 16:9. 2 min 17 s. [Online] Accessed August 20, 2024: http://sgnlr.com/works/on-screen/sisyfos-2011-strasbourg/.

Turner, V. (2016) Funeral. Full HD video, colour, sound, 16:9. 10 min. [Online] Accessed August 20, 2024: http://sgnlr.com/works/on-screen/funeral-2016-north-bohemia/.

Vincent + Feria (2010) Post Post Antarctica. Situations performatives. Paris: Editions Hallaca.