The Wool Urban Art Festival has been held annually in Covilhã, Portugal since 2011. The following is an edited transcript of a conversation held at Wool between renowned documentary photographer Martha Cooper and Nuart Journal Editor Susan Hansen.

Lara Seixo Rodrigues (Wool Festival Director): Welcome to Wool. Tonight, we are in a special place. This is called the Continent Room because the ceiling features a mural showing all of the continents that were known during the 17th century, when this was painted. So, I think this is the perfect place for us to receive Martha Cooper.

Susan Hansen: Tonight, we’ve decided to focus on one critical issue in particular, rather than having a more general conversation. This topic is the role of documentary photography in the heritage of graffiti and street art. My colleague Jacob Kimvall – a Swedish art historian who specialises in graffiti – talks about the role of the documentarian in graffiti subculture as being long recognised and respected, as photographic documentation is essential for the evolving life of the subculture. Indeed, Martha’s now iconic status is inextricably connected to her being one of the first, and certainly the most prolific and well-known documentarians of graffiti.

So, Martha, while you’re obviously a highly technically accomplished photographer and you have produced decades worth of aesthetically strong work, you’ve also played an ongoing role as an historian and an archivist. Why is this role so important?

Martha Cooper: As necessary as I once was, I think that today, there are many, many documentary photographers, and together, we are important. Every place now has their own documenters. But when I first started taking pictures in the late ‘70s of graffiti on film, not everyone had access to a camera. Now digital technology has advanced to the point that pretty much anybody can take a really good picture with their phone.

Do you still work with film or have you made the digital switch?

Never. I would never want to work with film again! I don’t understand people that think that film somehow is better than digital. Film is very slow. You need a lot of light to get a good picture. I think digital is better, it has its advantages. I mean, there’s so many things that I can do by myself now, like the post processing. I never could do colour post processing with film.

But that must mean that you’re amassing a lot of photographs, particularly with your digital camera?

I am. Hundreds of thousands. Millions! Well, maybe a million.

A million photographs! What an incredible re-source. Do you have any plans for archiving or cataloguing your photographs?

I’m in the process of archiving my photographs now. Which is a big job, but I feel it’s a necessary one. I have just sold my entire archive to the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. I have four years to get it all in, and I’ve started this process already. I’m trying to identify everything and put it in in some kind of order so that future researchers will be able to go to the Library of Congress and search for a name, a date, a place, or a festival and I’m making it so that people can use the pictures – not for advertising, but for editorial purposes. So, artists will be able to go and get pictures of their own work and use them. That’s the agreement. So that’s my plan for the next couple of years, and that’s what it’s going to take to prepare my archive for the Library of Congress.

This is very exciting news, but it sounds like a lot of work! Out of curiosity, I did a quick deep dive on the Library of Congress website before our conversation. With the search term ‘graffiti’, there were only 479 hits for images – and 100 of these were photographs of historical graffiti prior to style writing. So, the addition of your considerable archive represents a significant increase to the available visual documentation of graffiti and street art.

Yes. I should also mention that Henry Chalfant, my coauthor of Subway Art, is also working with the Library of Congress. So, both of our collections will be in the same place. I’ve also started a library at Urban Nation in Berlin. People give me a lot of street art books and I’m giving them all to the library. So, there will be a street art library to archive books on street art and graffiti for people to access.

That’s fantastic.

People are calling this the biggest art movement in the history of the world. And it’s important that these archives – and I would hope that every country has its own archives – are placed somewhere so that 5000 years from now, people will be able to access them in order to understand the way we’re looking at art history now, and at alternative forms of art histories.

Absolutely. This is a major institutional acquisition. Do you know which section of the Library of Congress your archives will be catalogued in?

My section is folklife, because I had done some documentary projects with them in the past that are catalogued in this section.

Do you feel that the positioning of graffiti and street art as belonging in the folklife section of the Library of Congress reflects the fact that these forms of art are still not being taken entirely seriously within major cultural institutions as a critical period in art history?

I don’t know whether it’s going to make any difference, but I would like to see graffiti and street art be taken a little more seriously by contemporary art museums. That would be my hope for the future. My hope is that museum curators will look at it more closely. But I don’t think I have had anything to do with the fact that is not the case now because I’ve seen and photographed so many wonderful graffiti pieces that are never talked about. And here in Covilhã I don’t mean the murals, but just the graffiti pieces around town. They’re inventive, colourful, fresh, interesting. And you know, these are kids doing it for each other. They have their own ideas about what they like about art. And I just would like to see that taken a little more seriously by contemporary art museums.

What is the role of documentary photography in achieving this?

I think that photography is really critical to the preservation of street art and graffiti, and I feel like my photographs are probably going to last longer than any of the walls that we see as we walk through the city. Some walls don’t even last for a year. Other walls last for five years, but it’s unusual to see a wall that lasts for, say, ten years in really good condition. So, how are those walls going to be preserved? From my point of view, the best way to preserve them is in good still photographs, which not just show the wall but also show the context of the neighbourhood the walls were painted in and if possible, the process of painting the wall, which is my specialty. I really like to be able to actually see the artists at work. I mean, anybody can take a picture of a finished wall. But there’s only a very limited period of time when the wall is being produced.

It’s essential to capture that process. I think this reflects a vital approach to heritage as it applies to graffiti and street art. This departs from a more traditional approach, which assumes that we should treat work on the street like art in a gallery or museum and put a heritage protection order on the finished work in order to preserve and restore it physically for all time. But the documentation of the life of the work in situ, including its production, as a form of living heritage, feels so important.

Martha, your approach effectively captures finished walls and their social and environmental context, but crucially, you also lean towards capturing process, and thus towards capturing some of the energy and the adrenaline, or the life of producing the work on the wall. That’s an energy that some claim is integral to these ephemeral art forms. The example we were talking about earlier is Keith Haring’s Crack is Wack wall.

Yes, that’s a very good heritage example because since Keith painted the Crack is Wack wall in 1986, it has been preserved and repeatedly repainted. But in the repainting, it loses something. Of course, whoever repainted it was probably a professional artist, but they are not Keith Haring. You know, they paint so carefully, and all the lines become very straight over time, that it loses the freshness and energy of the original.

So, it somehow loses its aura in the attempts to preserve it? Does restoration then paradoxically destroy art on the street?

Yeah, it becomes kind of petrified.

Do you feel that ephemerality is a defining part of this art form? The fact that it might fade over time, or be destroyed, or painted over?

I would agree that ephemerality is the defining part of this art form, and indeed if this were not an ephemeral form of art, I would not be so interested in photographing it. That’s what makes it interesting as a subject for photography – the fact that it isn’t going to last.

I discovered this morning that if you google Keith Haring murals in New York City, the first photograph that pops up is one of your process shots showing Keith in action painting in the 1980s, which really brings his work to life.

Yes, I think that shot is of him painting the Houston Bowery Wall, which like Crack is Wack was also repainted, but now it’s not there anymore. So, there was an attempt to restore it.

I didn’t realise that was an ultimately failed physical restoration attempt. I guess now the only real records of that work are through photographs such as yours, and the context they provide.

Audience: Martha, it seems very important you not just photograph pieces on trains or on walls. You also photograph the artist and the context where they are working. What’s the importance of context for your work?

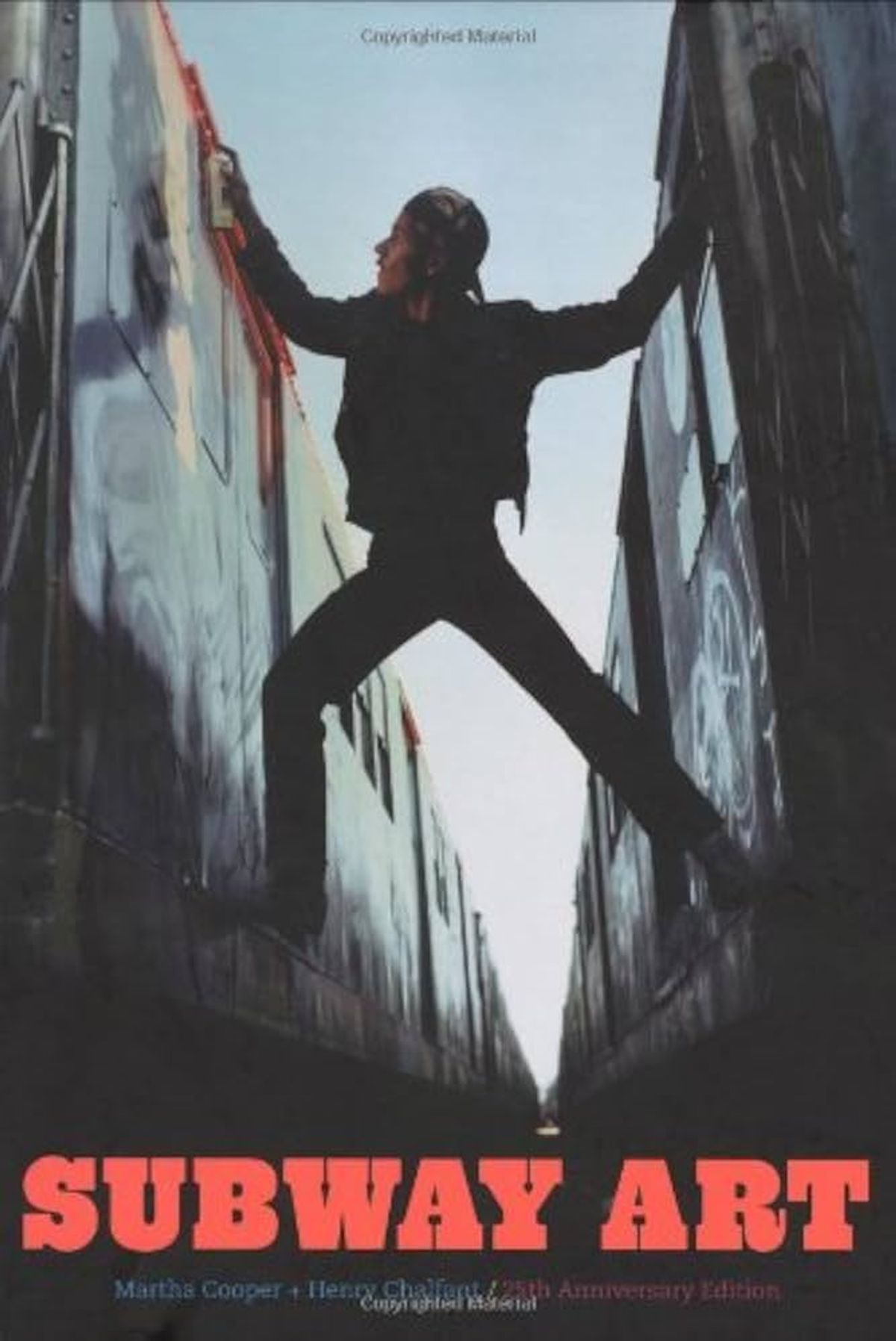

Well, the cover of Subway Art is Dondi painting in the yard. After I met Dondi, I explained to him that I had seen trains in New York and I’d spent a lot of time standing in vacant lots just waiting for painted trains to go by. But I didn’t really understand how those trains could be painted. And I kept asking him to please take me to the yards, which one night he finally did. And really, it was only because these trains are so huge, and because they were parked side by side, that they were able to stand up between them and get to the top of the train. It really was a revelation to me how these trains were painted. In order to paint a whole train [painting every car of a train], the windows were also painted just in case, this was not some random act of vandalism. And so, for me, that’s an important part of the story.

First, the graffiti writers make a plan. You have to decide which colours to take because it takes maybe 20 cans of paint. You’re sneaking into the yards through a little hole in the fence and you’re carrying these bags full of paint and it’s really dark. And while you have a sketch, you have to sort of memorise the colours in order to outline the piece. All of that was a mystery to me until I came along. And then the photographs tell the story. So, I think that was really important to capture.

It also feels important that you didn’t take the artists that were there out of the picture, you kept them in the frame.

Yeah, of course, but only with their permission! It wasn’t like I was sneaking around taking photographs. I do think it’s important to photograph what you see and what you know. And I always like to see what the artist looks like. So, it’s disappointing to me when an artist like Banksy won’t let me take a picture of him. You know, I’d like to see what he looks like! I think it’s interesting.

Did you think that the media distorted the reality of what those young people you hung out with and photographed were like? You know, they created these images of vandals just trying to destroy things. And you’re standing there seeing young kids interested in art. Did that feel frustrating at the time?

Yes. It was frustrating and I always tried to counter that vandal image with images that genuinely showed who they were and what they were doing. I mean, of course there was some real vandalism, but there was a lot more than that.

SH: Did that motivation – to counteract this pernicious ‘vandal’ discourse – affect the editorial composition of Subway Art? I’ve always wondered.

In the first edition of Subway Art, we even included a glossary of terms, and we explained graffiti a lot more. But by the time the current edition of the book was published, some decades later, we figured everybody knew those terms, so we didn’t explain them so much. Subway Art is now more of a photography book than the first book was. The first edition was published in England. We could not get it published in America. We sent it to 20 different US-based publishers, and they all hated graffiti so much. They were like, we have to look at this every day, we hate it and we are not publishing it!

And now it’s the most stolen book of all time?

Yeah, when it finally came out, the bookstores locked it in cases.

Audience: How was it like working in New York City in the ‘70s? The city seems to have been a crazy environment then – how difficult was it to capture this energy?

It felt adventurous, but I had a car, which was my secret weapon. So, I could drive around, and I used to take some of the writers in the car and go to the yard. Yeah, it felt exciting. But the city was bankrupt. And they had a lot worse crime to think about than graffiti. And still do. I mean, if you think of the South Bronx and the Lower East Side, lots of the buildings were destroyed, there were vacant lots everywhere, it was empty. Landlords were burning down their own buildings to claim insurance.

SH: Going back in time, I believe you studied anthropology at college? Do you think that you have an ethnographic eye when you pick up your camera? Is this perhaps why you have such a keen interest in the ‘human’ process shots and other aspects of the social context?

I was an art major and I did graduate work in anthropology. Yes, I think I’m looking at it from the point of view of an ethnologist. I mean, the thing about the process shots is that after the wall is finished, you really don’t even know what kind of paint was used. You don’t know whether the artists used a stencil or an edge and sprayed against it, or whether they picked things up from the ground and used those to paint, which I’ve seen artists do. Those are the kinds of details that you can document and maybe it’s not of interest to everybody, but it would be nice to have that process recorded along with the picture of the finished wall.

Audience: I’m a photographer and what I admire most in your work is the humanity you capture. It surprised me listening to you just now, that you studied anthropology, I didn’t know! I also think it is amazing that you got your pictures in the Library of Congress. In Lisbon, we put our pictures in the municipal archives.

Oh, it’s good to know your pictures are going to the municipal archives. That’s wonderful. Every country should have municipal archives for photography.

I see many efforts around the world regarding the conservation and preservation of street art, but these are mostly about protecting material heritage – the walls or the pieces themselves. So, I was wondering what your thoughts are about the immaterial part? The intangible part, or the memories that those walls leave to the community that lives with those walls?

Definitely, it should be part of the documentary process to try to record the memories that are associated with the wall as well as the memories of how the wall was painted. That’s important.

Whenever we go to a festival, everyone talks about the impact of the art on the local community, but what about the community of artists, producers, and documenters that festivals bring together worldwide – this community that we engage in together. How do you feel about that community?

The main emphasis is always on the local communities who are embracing the art that the artists are putting up. But you’re right, there’s another community that is of the artists themselves, and the documenters. It’s a wonderful community and we are now travelling from festival to festival, and we meet each other in different places around the world. I think the artists have been given a lot of incredible opportunities, without which the street art wouldn’t have happened, and it’s made their work very visible. I’m sure every artist has many stories of what their walls have led them to. Who knows what kinds of commissions have grown out of these festivals? And I have stories like that too as I get invited to other festivals because of these connections.

SH: But without photography, and especially in a smaller festival, is the audience for the work limited?

Well, photography allows many more people to see the work. I mean, how many people are actually going to see the mural in person compared to how many people now, especially with Instagram, are going to see a picture of the mural? But the artists themselves are taking very good pictures.

Audience: Has this helped? The fact that everyone has a camera? Or has this devalued the profession of being a professional photographer?

I’m definitely not as necessary as I used to be, but on the other hand it’s giving me a lot of visibility. I don’t know, I think it’s both. What do you think?

I think you’re right. I think it’s both. But if you’re a specialist in the field and you come to an event like this, you attract an audience that really wants to see what you’re doing and what you’re documenting. That’s not the case with somebody just walking down the street, taking a good picture.

Well, you never know who’s walking down the street and taking the picture. Anything can happen now with Instagram.

SH: Martha, I believe there’s another important collection of yours that has recently been acquired. In closing, could you tell people about this?

I have a collection of images of women photographers called Kodak Girl.com. So, when Kodak first developed cameras, they had an advertising icon, who was a woman – the Kodak girl. But somehow when I was growing up in the late ‘40s and then the ‘50s, photography was considered a man’s job. I was the only female photographer for The New York Post, and their first ever female photographer. That was in 1977, around the time I first started photographing graffiti. So, I have this collection that shows that women have always been photographers. You know, I’m just trying to make early female photographers more visible because there have always been many of us. When I don’t have a camera, it feels like something’s missing.