SUSAN HANSEN: With this exhibition in the Saar Historical Museum in Saarbrücken, Germany, it feels like you are consciously unsettling and rewriting our accepted narratives of graffiti and street art history. Why did you adopt such a critical curatorial strategy?

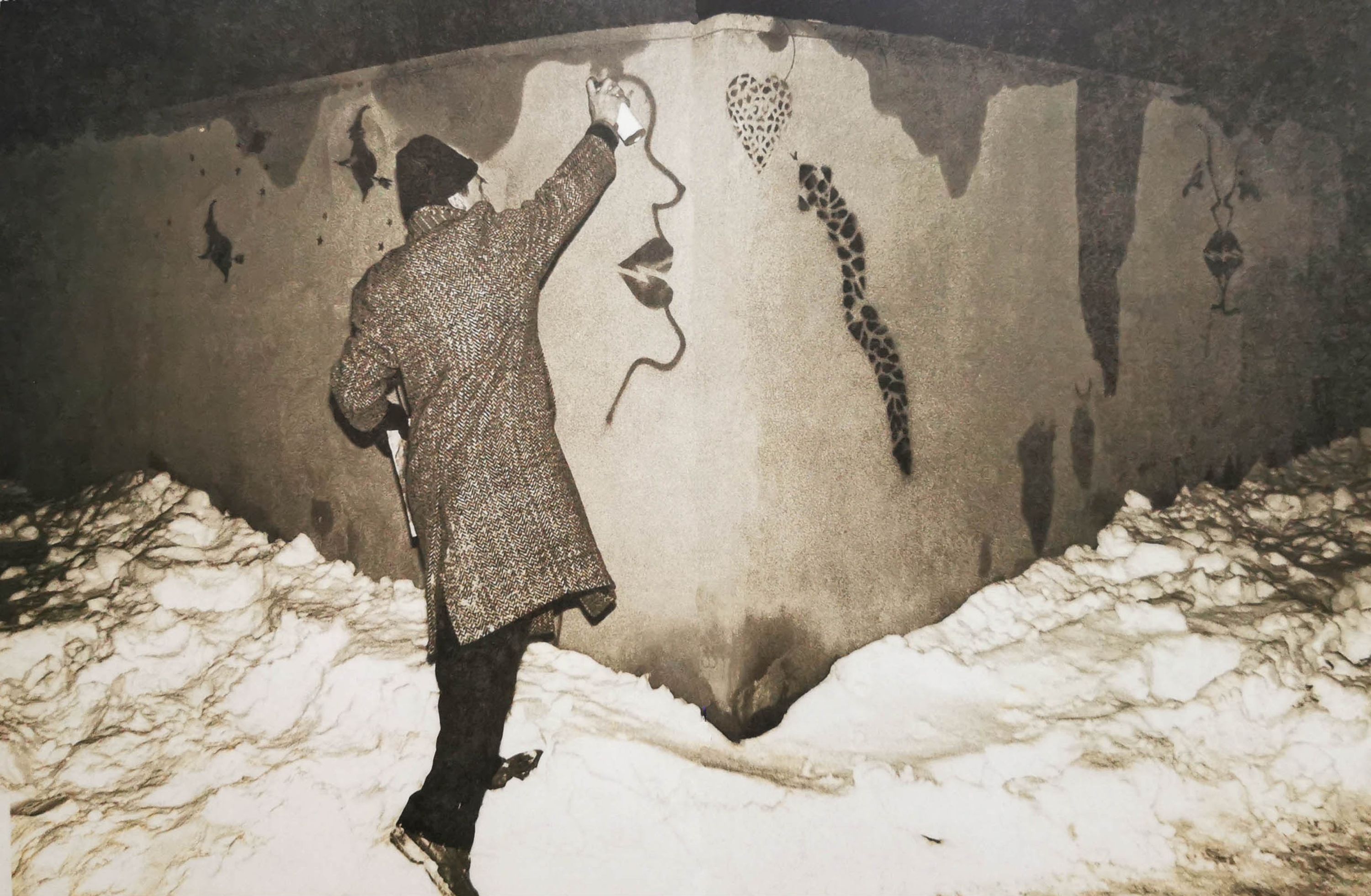

Ulrich Blanché: On the one hand, I wanted to show there is a canon and obviously I don’t want to change that canon completely. But I do want to question it, and I want to complicate it, so we can talk about our shared street art histories, whether in Germany, France, or Poland. We all use the English term ‘street art’ because there’s a kind of dominant narrative, or a history, that rests on the assumption that the Americans invented it, and that Europe was a blank canvas. That the inspiration for ‘street art’ originally came from the US, as did style writing graffiti. And then you have post-graffiti, but this is based on that same narrative. With this exhibition, I have tried to show that this is actually not true, and that this historical narrative is more like a construction we have imposed afterwards. The exhibition ends in 1995, the year in which Banksy’s earliest works appeared in England.

I also tried to show that there are many early examples of graffiti being welcomed with open arms. We knew from Amsterdam that there was a huge punk graffiti scene there. But we had art on the streets in every country. You just have to look for it. And to find this work, you need to use different search terms, not English terms like graffiti, style writing, street art, etc., but other terms that cross genres and borders, like conceptual art or political art.

It turns out that if you use slightly different search terms, you can find artists working very early on in the streets in Poland and Russia, and elsewhere around the world. The exhibition highlights, for instance, the work of Brazilian stencil artist Alex Vallauri. In the early 1980s, his work appeared earlier and had more impact worldwide than Blek le Rat’s work. People were inspired by Vallauri not just in New York, but also in Paris and Warsaw. Nobody knew his name. But they knew his work, which sparked stencil scenes all over the world.

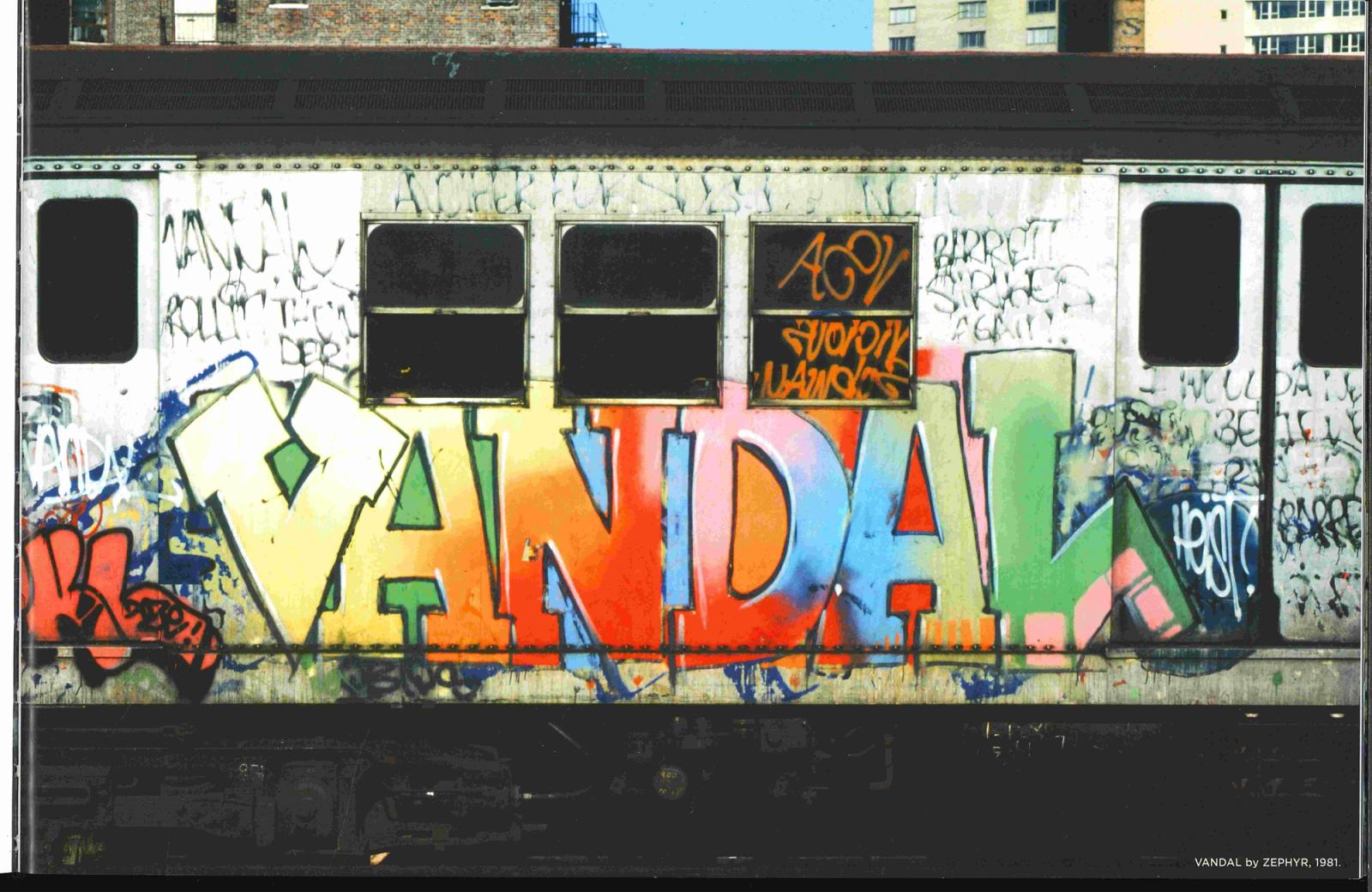

So, I wanted to trace those early examples and game changers. The ILLEGAL exhibition shows how art punk stencils by Crass influenced Banksy and Robert del Naja before they had even heard about Blek. There was also an international illegal street sticker campaign by Cavellini in the 1970s – well before OBEY in 1989. We also show LA cholo gang graffiti, Philly graffiti and pichação from Brazil – not just NYC-based style writing. But unfortunately, I just couldn’t show everything I wanted to include because of space restrictions and the fact that you can’t always get everything you want, in terms of securing permissions.

Catalogues for street art and graffiti exhibitions often have great visuals and maybe one strong essay, but the essays and authors that you have included in the catalogue for ILLEGAL make it more like a serious academic book. How did the essays inform the curation of the show, or were they developed together?

The catalogue and the show were developed together. For me, it was important to produce a bilingual [English and German] catalogue to show a wider audience that there is a history of street art and graffiti in various countries within the 1960–1995 time frame. There were some topics I really wanted to include in the catalogue that are not my specialty, and so these were the ones I outsourced. For example, there is a close connection between graffiti and other forms of artistic expression such as avant-garde art and literature, and also, in particular, popular music.

Many graffiti writers were not just visually creative, but they were also active musically, or they designed album covers. This dynamic interaction between visual art and music is part of the exhibition. As many of us know, the Swedish art historian Jacob Kimvall has an extensive collection of albums which feature graffiti on their covers, yet I’d never come across a text that explores this connection in detail. So, we were keen to include this.

Until I read Kimvall’s essay, I didn’t know the story about the Tuff City whole car being edited out of later editions of Subway Art once the authors discovered it was a ‘commercial’ piece!

[Reproduced below]:

[Given that] that the work was done by two of the most prominent artists, it is at first surprising to learn that the photo was not included in the extended and enlarged 25th anniversary edition of the book. The reason? The authors had found out that the graffiti piece ‘Tuff City’ was an early example of what would be referred to today as street marketing or guerrilla marketing, and thus found it too commercial to use… Tuff City Records is an independent New-York-based record label which had its first release in the very year ‘Tuff City’ was painted: a tune entitled ‘Beach Boy’ by Verticle Lines and featuring Phase 2 himself (Kimvall in Blanché, 2024: 54).

Who else did you invite to contribute an essay to the catalogue?

I really wanted to include an essay on street art and politics so I invited Sven Niemann to write one as he has dealt with this before extensively. But two books were published on this topic last year and I didn’t want to reproduce them. I wanted a new essay that would encapsulate what we know about street art and politics. I also wanted to explore some lesser-known precursors, like the New York jazz graffiti artists from the ‘50s and the French poets who have such a strong connection with both visual art and graffiti.

Another consideration was that this is an exhibition in a museum that is in a region of Germany that borders France, and we wanted it to have some connection to the local area and its history. So, for the big pieces, the life-size works, we tried to show art from international graffiti and street art history. We also included a map tracing how street art and graffiti arrived in the area and showing all of the earliest pieces of illegal art that we could find on local walls, such as stencils. As I’m not an expert on the art from this region, I asked Myriama Idir, who is a French specialist for the Grande Région, to write an essay for the catalogue.

In ILLEGAL, you bring to light some otherwise unknown – or hardly known – artists and writers, with a focus on women artists. In doing so, you destabilise our androcentric and heteronormative assumptions about the typical street artist or graffiti writer. Most official histories assume that the key players in these movements were cis-men.

The show includes lots of artists that clearly played a role at the time they were up. Today, TAKI 183 and writers featured in Subway Art are still recognised internationally. So is Cornbread, who’s in the show as well, of course. Over time, these artists have continued to speak about their role, and they’ve written themselves into history. But there are other writers and artists, like Barbara 62 or Vampirella, who also played interesting roles at the time they were active on the streets, but who would not come out publicly again after. They disappeared. Somehow, they didn’t feel the urge to step out at a later stage and say ‘I was Barbara 62. I was the person who did that’.

And so, many early female artists didn’t get a voice and haven’t become part of our official histories. But in my research for the show, I found out that Barbara 62 and Eva 62 played a much more important role than has been previously acknowledged. Apart from being the first female writers in New York, they played a crucial role in that they were the first writers we know of to move between the tag and the piece. So, it turns out that they did something radically new, which nobody had done before, whether male or female. They were not just the first female artists, but the first artists to do that. In finding examples like this, I tried to contradict the usual narratives.

The virtual tour of ILLEGAL gives a good sense of the layout of the exhibition and it’s cool that it’s also interactive – it really gives remote viewers an appreciation of how you’ve used the museum space. You’ve got some works that look like they are almost life-sized in scale, and you’ve got some entire walls that look monumental through the use of projection.

There are moving images on the walls of the exhibition, but unfortunately, these did not translate to the 3D tour. We had to freeze the projections because we could not capture moving images using this method and – during the one hour when this guy walked around with his camera to take all the footage for the 3D environment – I had to choose one screenshot for each projection that represented it well. Apart from that, all the posters and prints are visible in the virtual tour, and you get an impression of the scale of the artworks within the space, so that works well.

Your use of space feels deliberately different to the ways in which shows on street art and graffiti tend to conventionally approach museum space. How did you use the museum differently to bring this work to life, and why was this important?

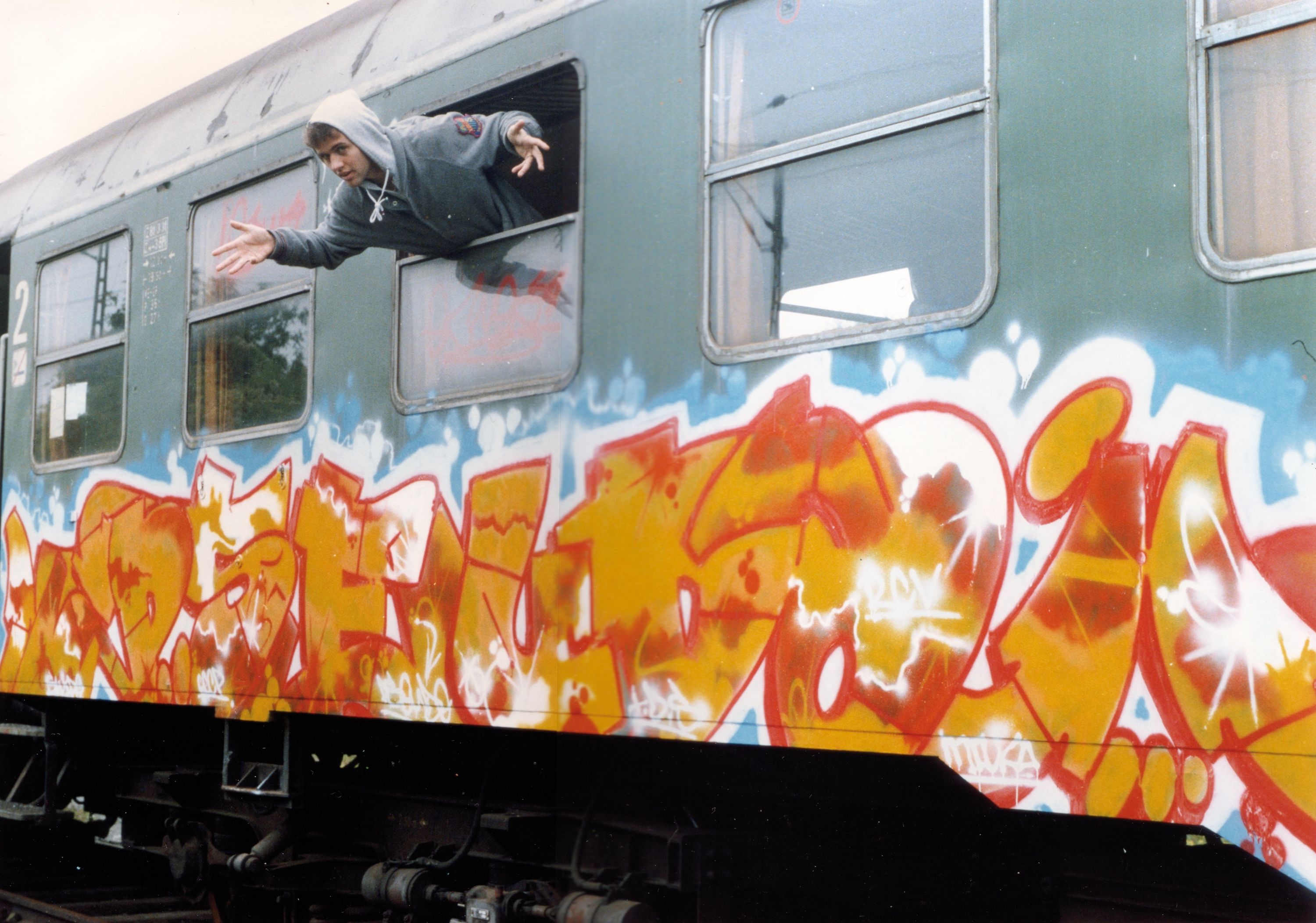

Many so-called street art exhibitions show work on canvas, or other studio-based work by artists who have also done interesting work illegally on the street. But painting a subway train on a canvas, or putting some tags on a canvas, is not the real thing for me. So, I tried to be consistent in not including any non-illegal works in this exhibition.

So, anything that’s legal was barred. No studio-based work allowed?

In principle, yes. But of course, there are exceptions. There are a few studio-based artefacts in the exhibition. For example, we show the stencils that were used as tools to do vandalism. These were obviously prepared in advance in the studio, as were the posters that were then pasted in the street, but for this exhibition, focussing on real vandalism was the goal. So, most of the works in the show are illegal.

In which other ways is this show different from other museum-based street art exhibitions?

The second thing I hate about most street art exhibitions is that they usually just speak to your mind and not to your body. That means you often have lots of little photos. The trains captured by Henry Chalfant for example – which were like 16 to 24 metres long – are usually shown as hundreds of small-scale photos, which is an overwhelming visual experience for the viewer. I think it’s more interesting to look at just a few works, but at a scale that is closer to the length and height they were to the viewer’s eye at the time they were created. It is only in this way that we can appreciate – to some extent – the phenomenological effect of a whole car running past you, or a Shadowman by Richard Hambleton leaping onto a wall. So, that was a tactic.

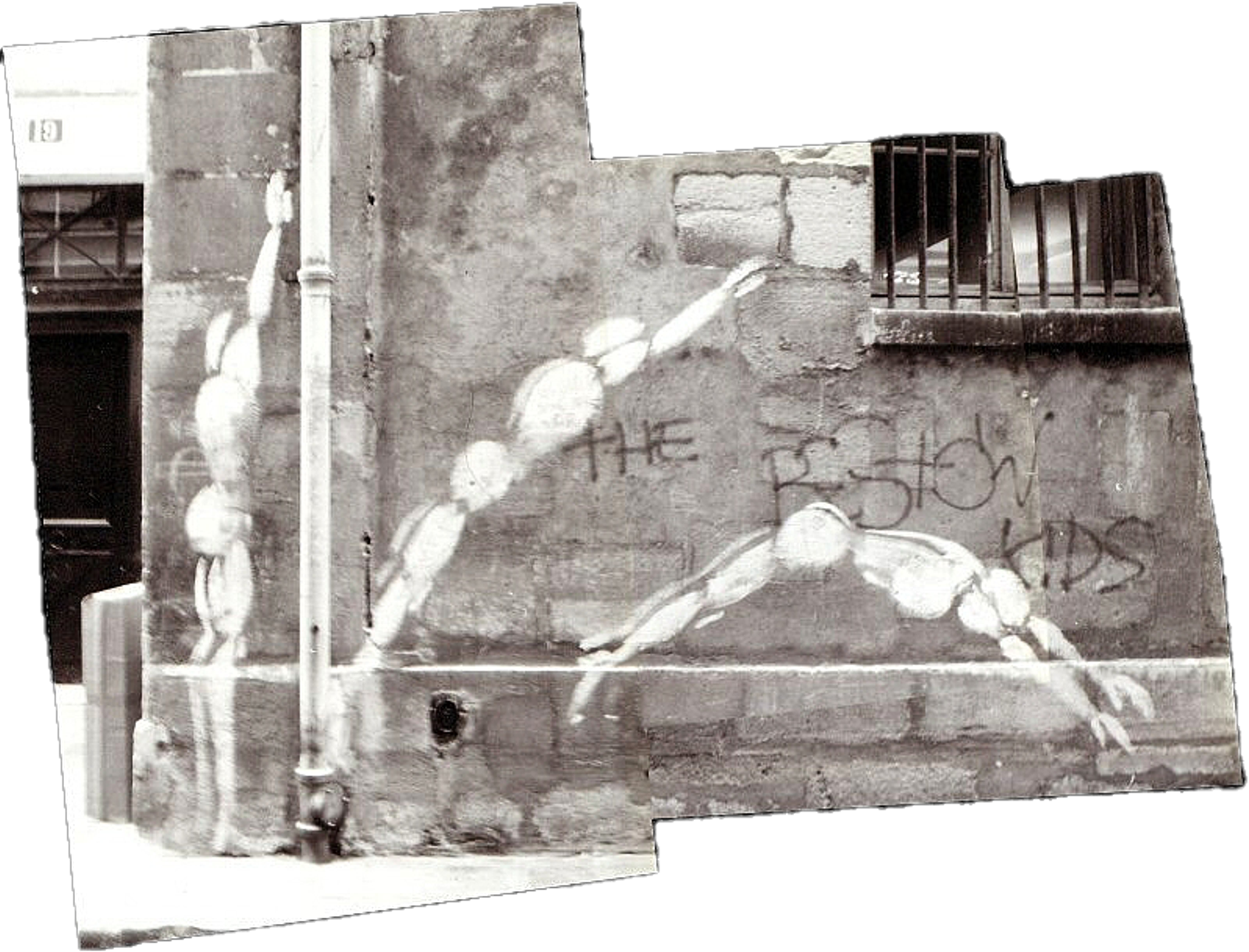

The third thing I dislike is that showing developments over time is often neglected in street art exhibitions. I know you also work with repeat photography – or photographing the same walls over time. But 1960 to 1995 was such an early, historic period for street art. People usually didn’t photograph the same wall again and again and again to show progress – not that many people had cameras anyway. So I had to research a lot. And I found photos by different photographers who didn’t know about each other, but who took photos of the same walls at different times. I put together a timelapse projection where you can see walls at the first stage, and then a later stage, with new work coming up again and again. I tried to make this kind of dialogue visible.

I had no idea that Brassaï was doing repeat photography of graffiti in Paris way back in the 1930s!

Yes, he was. He came back to certain walls to see how the graffiti looked that he had originally photographed 15 or 20 years earlier. That’s the very first example I know of that deals just with graffiti as a subject that’s not just somewhere in the background.

The final thing I hate about street art exhibitions is that usually when photos of street works are included, these works are always shown in a state of perfection. A state reached the moment that the can drops. But that’s not representative of most works on the street, because they have a development over time, they change and become even more interesting. They are not just this pristine perfect thing.

The coffee table book version of street art we see on Instagram?

Exactly. So, I wanted to focus on entire walls and not just separate individual works, to show the ephemerality and decay of street art and graffiti, and the life of the city’s surfaces over time – not just the perfection of the work immediately after it was created.

There are a lot of artists who claim a particular wall, and every time somebody paints over their work, they come back and do a new piece. In the exhibition, we included the Aachener Wandmaler [Aachen Muralists], an artist duo who for over six years painted on the same wall several times. They made their last work in 1983 and it’s still there. It’s one of only five works in the German speaking countries that are under official state heritage protection. They were created illegally, but are now officially protected. The Aachener Wandmaler were a gay couple and the first queer street artists I know of in Germany – and indeed in the rest of the world. It’s not that easy to find early queer street art that’s not just activism – gay rights and slogans – but visual art that deals with queer subjects, and this is in the late 1970s.

We’ve been talking about ILLEGAL mostly as academics with prior knowledge of the field, but what is it that you’d like everyday visitors to take away from their experience of the exhibition?

I think about, what do they know? What does the average person already know about street art and graffiti? And that’s usually Banksy, and a bit of what they see in their own streets. Most people who come to this exhibition are from this area: Saarbrücken and the surrounding cities. A ten-minute car ride away, there’s a big outdoor exhibition in Völklingen, a UNESCO World Heritage site which has hosted an Urban Art Biennale since 2011. So, I knew that the visitors would probably come to visit both the museum and the Biennale. The Biennale is held at a former industrial site that is now a ruin. The curators invite the usual suspects to paint legal murals there. It’s very impressive. But it’s just one (legal) side of the coin and I try to show people the other side.

Do you think that German museums are more receptive to a show involving graffiti and street art than museums in other countries?

If we look at the graffiti and street art shows and events hosted recently in German museums, such as this exhibition in Saarbrücken, or Javier Abarca’s recent Tag and Unlock events in Munich and Hamburg, it’s important to note that these are not art museums, they are historical museums. And that is a big difference. German art museums are still hostile to street art and graffiti, so we still have a problem. The only art museums that show this kind of work are places like Urban Nation in Berlin or the Museum of Urban and Contemporary Art [MUCA] in Munich – but these are run by private collectors or big companies.

In Germany, art museums equivalent to the UK’s Tate wouldn’t show street art or graffiti, and I think the reason for that is because having to connect to their local community is not a prerequisite for receiving the funding they get, as it is for British museums. And there is an assumption that local communities hate vandalism! But what I like about British museums is that they really engage local communities, and children, and people who are not art specialists, which is often missing in Germany.

In France it is more possible to show graffiti in art museums – like Christian Omodeo’s recent exhibition ‘Loading: Street Art in the Digital Age’ at the Grand Palais Immersif in Paris. I’ve just had a visit from Susana Gállego Cuesta, the director of the Nancy Museum of Fine Arts who is very much into street art and graffiti. She came to see ILLEGAL with two curators: former graffiti writers Patrice Poch and Nicolas Gzeley. They are working together to take over a current exhibition of French spray paint art. They were very interested in the way in which we used the museum space for the show, with large scale projection and life-sized photography.

So, ILLEGAL may have an influence on the use of museum space in other street art and graffiti museum shows?

Hopefully, or at least they will see that there are some other possibilities beyond the usual options!

Do you have any plans to host the exhibition anywhere else?

Yes, the exhibition could travel. It would be an easy show to travel with, because it’s mostly not original works – all of those were destroyed 40 years ago. And even though the show takes up a lot of space in the museum, it’s not that expensive to produce because it’s mostly projections and printed photographs, as these are the only records we have. Of course, we do have a few original works here and there too, but these could travel also because I have good connections to the collectors.

Without photo-documentation, we couldn’t show the history of street art and graffiti?

Yes, without photography all of these works would be lost, and historical exhibitions like ILLEGAL would not be possible.

So, perhaps the one thing you might have to do in a different city in another part of the world would be to rework those parts of the exhibition that are place specific?

Exactly. As I said, there is one part of the show that’s very much about East French and West German street art and graffiti history. But if ILLEGAL were to travel to a different city, I would replace that wall by constructing a new map showing ‘who was the first in this region?’ To start locally gives us a different way into the history of street art and graffiti, which is important in correcting the dominant narrative that everything, everywhere, stems from Wild Style, Spray Can Art, and Subway Art. In local histories you will often find lone wolves working on the streets, who got their inspiration from the strangest places – an advertisement, a film, a record cover, or a music video. Or perhaps they saw someone’s photos of their trip to a different city, and they started their own local scene. Street art and graffiti did not start centrally just in Paris and New York to then spread to the rest of the world. In the days before social media, people in different countries were developing their work independently from and in parallel with each other without there being much direct contact.

Ulrich Blanché has been researching and teaching at Heidelberg University, Germany, since 2012, initially as a research associate. Since 2021 he’s been a regular private lecturer at Heidelberg University (where he has just completed his research project ‘A Street Art History of Stencils’), at the Heidelberg University of Education and at the Heidelberg Centre of Transcultural Studies. In 2021 he finished his postdoctoral dissertation titled Monkeys in Pictures since 1859. His dissertation on consumer culture and commerce in Banksy and Damien Hirst was published in German in 2012, and in English in 2016. Blanché has edited the exhibition catalogue Stencil Stories: History of Stencil Graffiti (HeiBOOKS, 2022) and co-edited the anthology Urban Art: Creating the Urban with Art (Urban Creativity, 2018). In 2024, he curated an exhibition on the history of unsanctioned urban art at the Saar Historical Museum in Saarbrücken, Germany.

ILLEGAL: Street Art and Graffiti 1960–1995, May 18, 2024 – February 23, 2025. Details and 3D Virtual Tour: https://www.historisches-museum.org/illegal-street-art-graffiti-1960-1995

Blanché, U. (2024) Illegal Street Art Graffiti 1960–1995. Munich: Hirmer Verlag.

The ILLEGAL exhibition's finissage will feature a conference on Art & Place, co-directed by Ulrich Blanché and Javier Abarca (of Unlock/Tag). This will be held in Saarbrücken in February 2025.