It is two in the morning on a regular Saturday, we went out for drinks with Fun. While he is tagging, someone suddenly starts yelling at us from the darkness of the streets − ‘oee, oee hand me that can!’ We were petrified, thinking we would get mugged. Along comes a man aged around 45, saying ‘Calm down ’pana’[mate], I am Fantasma 77, I tag too, but I do the chapeteo…’ First frame.

‘My number must never be forgotten. My name is Plomo and my last name is Seventysix. Plomo 76’, he said astutely when I asked him to explain the number next to his ‘chapa’ [tag], which I had stupidly overlooked at first…Second frame.

‘Chapeoin Guayaquil is not bound by limits’, Yinsu 96 said when I asked him where in town I could find chapeo. Third frame.

Introduction

‘Young people are the mirror of the society in which they live, in the reflection of their problems they throw back an image that we usually don't want to see.’ Nelsa Curbelo

The present paper deals with chapeteo,a type of urban mark making in Guayaquil, Ecuador, that is usually marginalised and condemned for its association with gang culture and crime. It began in the late 1980s and continued all the way through the '90s and early 2000s, meaning there are at least three different generations of chapeadores. This in-depth reflection of chapeteo starts with a brief description of the context of Guayaquil and the key characteristics of this city.

Guayaquil is the largest city in Ecuador and also the country's main port. It has a diverse population composed of people of (mixed) indigenous, European, and African descent as well as economic migrants from the Ecuadorian Andes known as Sierra. Most people work in the fields of commerce and trade. In the words of theorist Francisco García Serrano (2013: 204)

Guayaquil is not only the largest urban conglomerate in Ecuador, it is also a symbol of strength, development, and modernity. Since its foundation in 1537, this city turned into a strategic port for commerce between the Pacific coasts and the Caribbean. Guayaquil constitutes the main hub for the agroindustry, commerce, port services and tourism in Ecuador.

Guayaquil has a large urban concentration formed by 16 parishes: Ayacucho, Bolívar, Carbo, Chongón, Febres Cordero, García Moreno, Letamendi, Olmedo, Pascuales, Roca, Rocafuerte, Sucre, Ximena, Urdaneta, Tarqui and Nueve de Octubre. Geographically these parishes are divided into northern, central, southern, eastern and western zones. The parishes have certain southern and northern neighbourhoods that are considered traditional: Centenario, Urdesa, Las Peñas, and Alborada among others. Certain other areas are flagged as dangerous such as Guasmo, Cristo del Consuelo, La Floresta, Monte Sinaí, Bastión Popular, El Fortín, and El Suburbio. During the '80s and '90s, much of the city faced a lack of basic services, unhealthy living conditions, chaos, and insecurity. This situation went hand in hand with excessive and disorderly population growth and the absence of public policies to regulate public spaces and manage community zones. In terms of access to education and employment, the situation was far from optimistic either. It seems like the uncontrolled traits of a Guayaquil that was in the process of development and expansion, created the right breeding ground for the emergence of various forms of youth organisations in search of their own scene and place in the city. The fact that Guayaquil has a much higher population density than the rest of the country equally triggered the emergence of the so-called pandillas (gangs). All the aforementioned factors contributed to the surfacing of these gangs in this exceptional moment in time for Guayaquil.

In 2004, the Uruguayan human rights activist Nelsa Curbelo published a paper titled ‘Cultural Expressions as Agents of Change in Violent Youth Groups’. Its pages contain an attempt to trace the genealogy of the gangs and ‘nations’ in Guayaquil. The publication established that gangs were formed by mixed groups of men and women between the ages of 13 and 30 and united by bonds of friendship (Curbelo, 2004). In this regard Curbelo (2004: 9) points out:

The gangs are groups of young people made up of about 20 to 30 members aged between 13 and 30. They do not follow hierarchical orders, nor have set rules. Both men and women join these groups that gather in parks to talk, trace routes and plan the execution of muggings and thefts. They use specific slang to express themselves such as echar cabeza (‘throw head’) that refers to the act of observing people who pass by.

In turn, researcher Blanca Rivera (2019: 9) highlights that:

According to data collected by DINAPEN, in the province of Guayaquil in 2003, there were 404 gangs, which represents 57% of the national total. According to this special police unit for children and adolescents, that same year the number of adolescents arrested for graffiti offences, unlawful association, suspicious behaviour, damage to private property, drug consumption, and rows, was 10,141 out of 19,640, i.e. 52% of all arrests.

Those were violent times in Guayaquil − times in which family breakdowns related partly to cases of migratory movements created dysfunctional homes that left children in a state of affective deprivation and loneliness. Soon enough, the gangs would appear to these children as a family substitute, an acquired family willing to embrace them and provide them with the protection and affection they could not find at home. As Snop 10 states in the interview transcribed further on:

A lack of love, we all have the same story. Moms acting as both mom and dad. Divorce, stepfathers, stepmothers. We would go out on the streets searching for the attention we couldn’t find at home. In the gangs we would find all the love we needed, food, someone saying ‘hello, how are you?’. If we didn’t have what we needed, we would go out to steal.

This need for bonds and well-being pushed the youngsters to commit illegal acts to get food to satiate their hunger, get spray cans to tag, and to throw dance parties for all gang members to enjoy. According to the aforementioned ethnographic study, kids would typically join a gang between the ages of 8 and 13 and stay a member for up to a decade. Due to the precarious situation of these groups, it is certain they would all be involved in minor to medium-level criminal acts.

There were major confrontations between rival gangs throughout the city of Guayaquil. The best known gangs were Los Contras, New People, Marea Negra, Cherooke, Gobernantes del Norte, and New Rebel, among others. In the words of Curbelo (2004: 2):

The hypothesis I propose is that the gang member poses a way of living the city, the polis. Therefore, we are faced with a political event, with its own codes, alphabets, music, slang, and structures that represent a culture in which the use of power is always present, even if the various groups define themselves as underground and clandestine.

In addition to the elements that create cohesion within gangs through an exercise of power understood as violence, it is the politics of affectivity that played a decisive role in the forging of their culture. The deep bonds of friendship and loyalty existent in those days endure in many of the surviving members to this day.

We are thus faced with a scene formed by armed youngsters united in brotherhood who have the specific need to articulate themselves in relation to other realities in response to their shortcomings. Their precariousness originated in their domestic situation and was increased by a government that would not guarantee them even their most basic rights as citizens. As the chapeadores point out in the interviews, it was this same government that criminalised them and aimed to wipe them off the streets through different unofficial social cleansing operations.

Chapeo: genesis, gangs, Guayaquil, and the people

'Chapeo appeared when the gangs were booming.'

Plomo 76

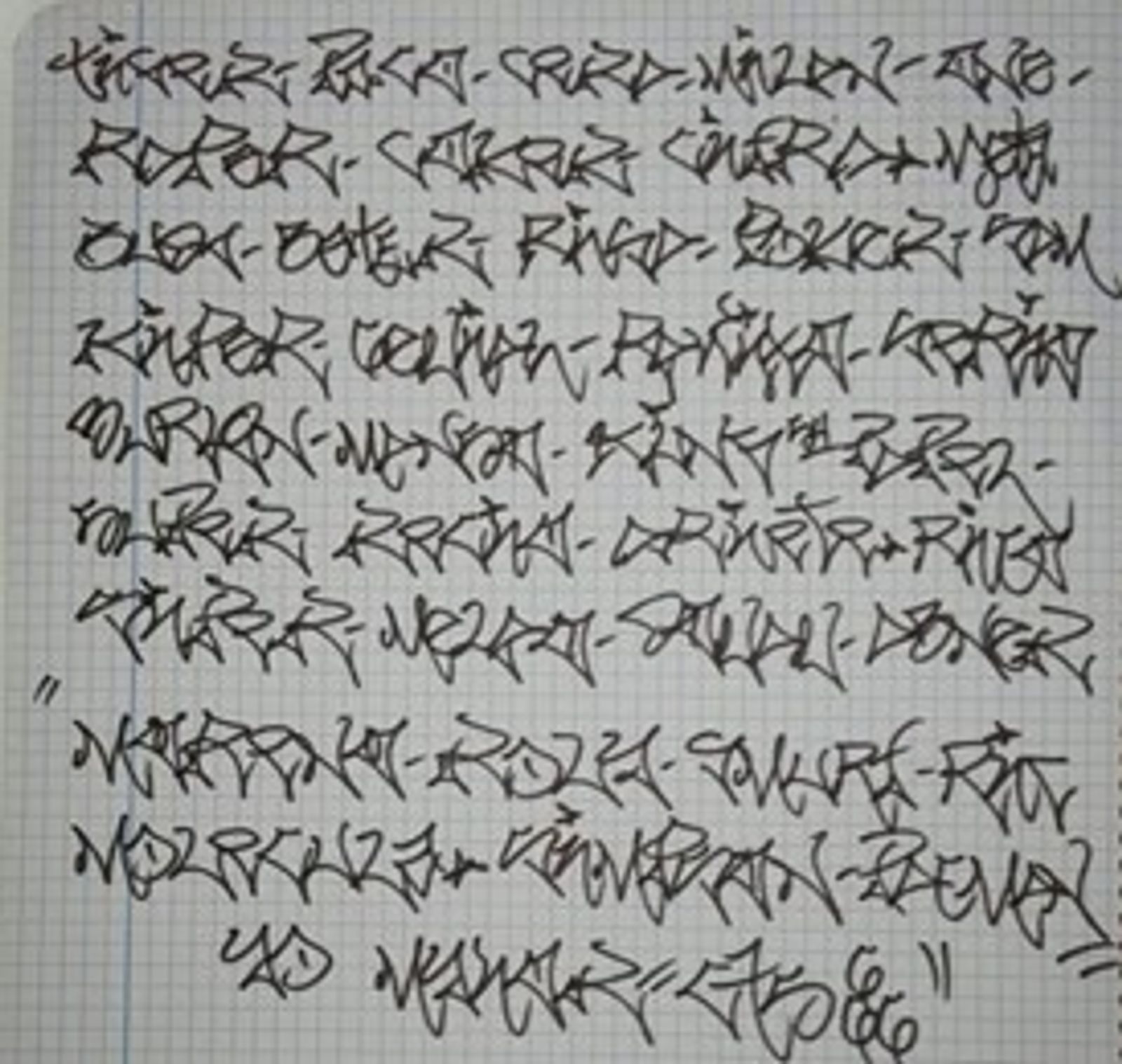

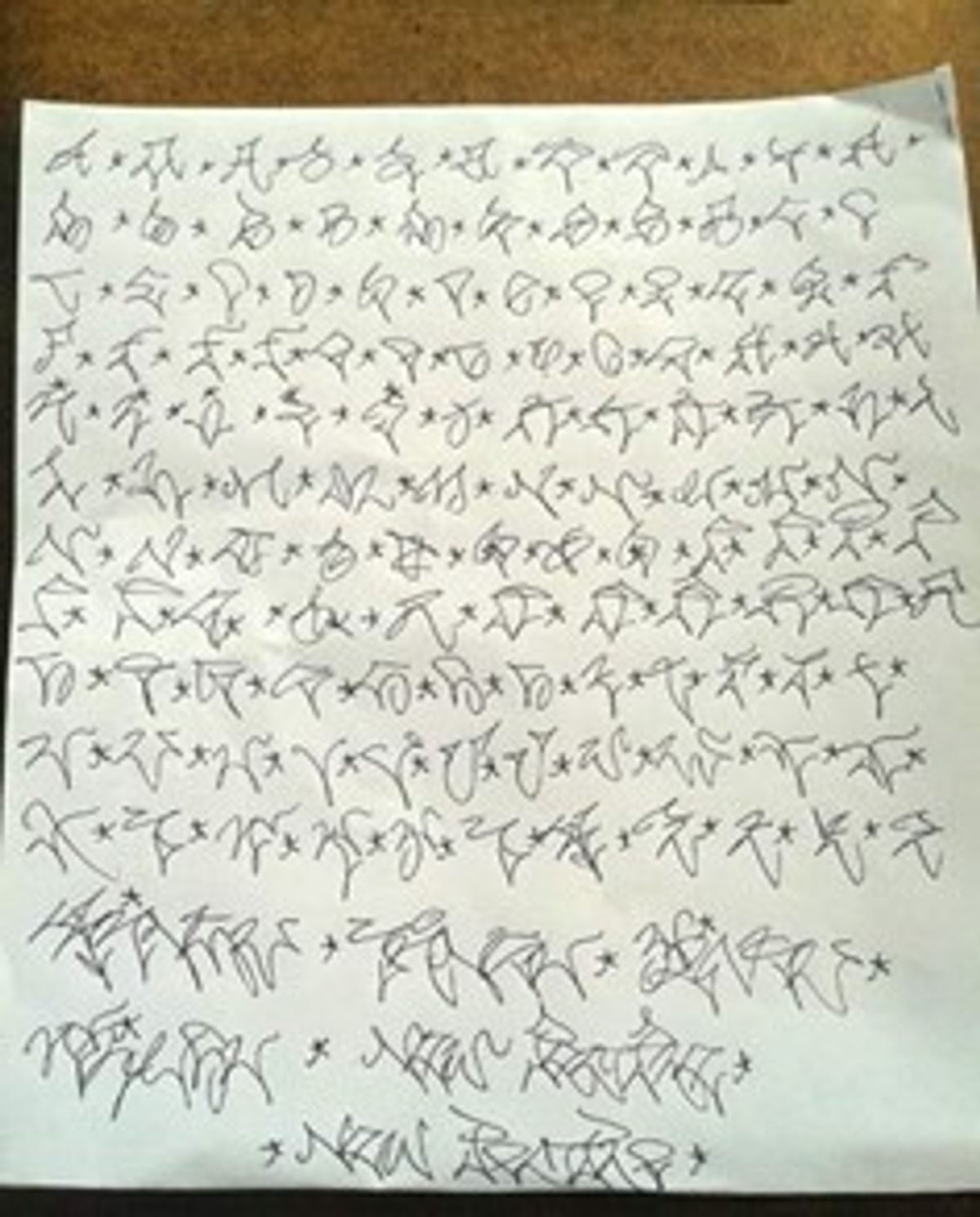

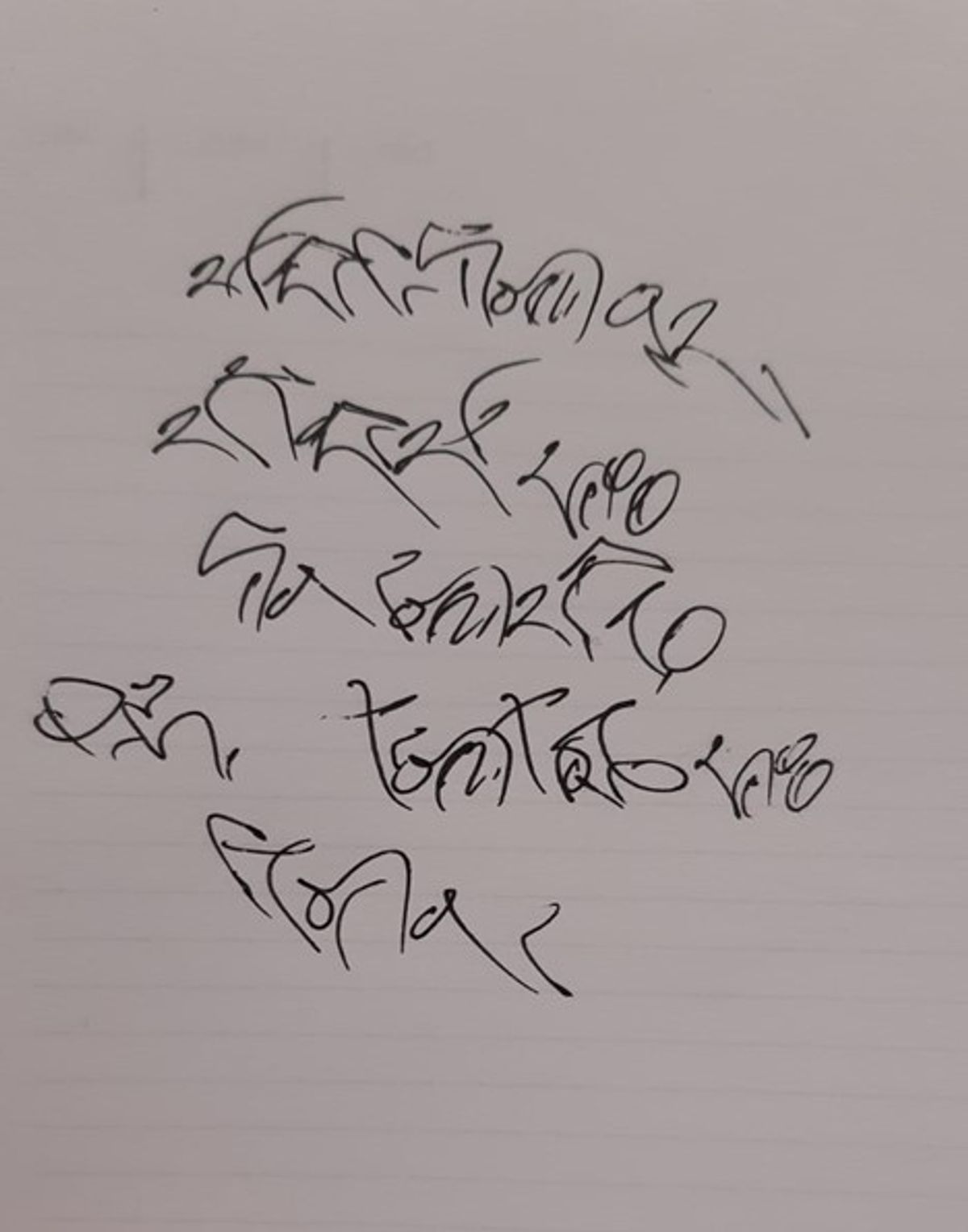

Chapeo is a form of urban calligraphy particular to the city of Guayaquil, widely known also as chapeteo or letra pandillera (gang writing). Very unique in terms of style, its name derives from the word chapa (badge, tag) meaning nickname − the nickname of each member of the gang. This name would be accompanied by a number that identified the bus line the gang members used to commute home with, for example Fantasma 77. Usually the tag would be executed in black, blue, and red in an aesthetic that is reminiscent of gothic writing: a cursive or brittle ductus to reduce the number of strokes and endow the writing with agility. Snop 10, one of the interviewees, explained that formerly these writings were made with the blood of their adversaries but nowadays they use spray paint. The origins of chapeteo go back to a reinterpretation of the alphabet performed by the gangs to establish their very own impenetrable system of communication.

It is important to mention that each gang had their own alphabet that allowed them to differentiate from others and foster a sense of belonging among its members. The most appreciated chapeadores were those who would leave the highest number of marks − marks that would instantly be recognised by their peers because of their style. Mastering this type of calligraphy was key to becoming part of these groups. On the basis of extensive observation, fieldwork, and conducting interviews, three main causes and purposes of the advent of chapeocan be listed:

1. Gang activity. As highlighted before, chapeo can be identified as a specific type of calligraphy and writing system, created with the aim to characterise each gang. It is configured as a distinctive form of communication and as a parallel, encrypted language, which to certain extent works as a true contemporary codex.

2. Classic territorial marking. It can be inferred from the interviews that the rivalry between gangs included chapeo wars, in which each group would compete to have the highest number of tags spread around the city (these would be actually counted). It should be noted that the first and second generation of tags represented the names of the gangs, it was only later that gang members would tag in their personal capacity. Either way, tagging in rivals’ territories was a major challenge so whoever managed to do so gained a lot of respect and fame among peers – which obviously brings to mind the traditional New York City graffiti practice.

3. Rivalry between educational institutions. Two public boys’ schools that were emblematic in Guayaquil were key in detonating the chapeteo phenomenon amongst the students: Colegio Fiscal Aguirre Abad founded in 1944 and Colegio Nacional Vicente Rocafuerte created in 1990. The interviewees explained that many gang members were enrolled in these institutions and that there was no lack of classic rivalries when it came to ball games, other competitions, and of course chapeteo battles.

Considering the above, it is of major significance to look into this type of inscription in public space, not least in relation to the history of the city and its generational changes. Moreover, the study of these inscriptions comes in response to a growing need to identify, analyse, and highlight other organic forms of urban writing and graffiti that go beyond the well-known Time Square Show and the boom of New York City's graffiti. Acknowledging chapeteo and discussing it side by side with similar manifestations such as pichação in Brazil or ganchos from Monterrey, does justice to a style of resistance fraught with sociocultural, political, and economic heritage – a style which, according to some, should not be recognised and should be erased from the official memory merely because of the criminal and violent implications associated with it. I will expand on this point further on.

To try to reconstruct the Guayaquil phenomenon is to trace the chronicles and testimonies of the disruptive existences within the city with the purpose of bringing to light their positive sides. Systematising this street reality is a strategy to avert its extinction and respond to the recurring criminalisation of graffiti movements in Latin America. Moreover, writing about chapeteo is valuing the presence of an entire generation of youths in Guayaquil whose street life existence was traversed by profound problems such as unemployment, lack of family protection, lack of spaces for cultural cohesion, and violence. Leaving traces in the urban environment was a way for them to give expression to their situation. Chapeteo was thus the visual representation of a struggle to find and preserve an identity both as gang members and as adolescents in the city.

Mapping the activity of chapeteo is in itself a political act and a direct testimony of the factors triggering conflict in the city: the dissatisfaction, the disarray, the violence, and the grotesque. To write about chapeteo is to confront the normative way of writing history and the common need to remember what is beautiful and permitted, what is clean and acceptable, leaving aside those traces, imprints, and whispers that most scholars prefer to ignore, erase and forget. Chapeteo manifests itself as an annoying and disturbing presence that wrecks the failing aspirations of the modern project of Guayaquil as a progressive and emancipated city. In this respect, history will always choose to look the other way and eliminate everything that reminds us of the cracks and fissures through which the manifestations of discomfort arise as scars of their own times.

Writing about chapeteo is part of an historical debt to all those dissenting, unruly, and malicious aesthetics obscured by the hegemony of high art and culture. From the interviews held for this paper and throughout my trajectory as a researcher of graffiti culture and street art, it can be affirmed that there is in fact a violent, criminal, and gangster-like undertone to chapeteo. These aspects are inherent to its context and marginalising or trying to erase its presence from the urban history of Guayaquil is pointless. This style is so unique and local it cannot be undone by moral judgments. There are multiple dimensions to these public space interventions and the words play, fun, innocence, and vibrancy spring to mind first and foremost. Yet, each trace also carries a sense of belonging, complicity, and affectivity. Entire generations trying to withstand hardship found a common language in chapeteo. Groups of youngsters that threatened the facade of the city and honoured the abject and repulsive. Their calligraphic lines stem from the distinctive visual elements of Guayaquil's youth associations. Irrespective of the notion of good and bad, chapeteo points to the human dimension in terms of inhabiting the city. According to Spanish theorist Fernando Figueroa – who in his text ‘Signature Graffiti’ expands on this human dimension (Figueroa, 2014) – there is a need of collecting these types of urban experiences even if they are uncomfortable to some. After all, the remembrance of the bad is inevitably an extension of what it is to be human.

In a different sense, chapeteo is also the legacy of the increasing importance of masculinity in the context of Guayaquil. There is a feminine presence in the series of interviews conducted for this research, yet women in gangs played less prominent roles, being mostly ‘companions’ who did not aspire to be decision-makers or protagonists. Both the rivalry between male gang members as well as the initiation rituals − that included robbery, beatings, and other physical confrontations – were masculine in nature insomuch as they affirmed power through the identification of the strongest and toughest. These characteristics are typical of a militia forged in the neighbourhoods and classrooms of Guayaquil. Consequently, chapeo has strong features also in terms of aesthetics: elongated, jarring, and aggressive lines and deep markings. In this sense, this type of calligraphy is an exercise of power that subverts the established order in an arbitrary manner. The one who does chapeteo is in control of the wall, is the winner and master of the territory. With a spray can in hand and backed up by their gangs, chapeadores all felt invincible.

With regard to the music that accompanied chapeteo, it is somewhat remarkable to find that the writers would listen to nineties techno, Panamanian reggae, house, and boricua house. These musical genres invited gang members to measure their strength through dancing, not only on the streets, but also in the first nightclubs of that time: Latin Palace, Forever, Magnate, and La Terraza. This is the playful and affective side to chapeteo which shows that it is a social phenomenon that integrates different manifestations of urban culture. These particularities were found in the interviews and upon review of first-hand testimonies. On the crossroad between the fraternity, the city, the rhythms, and the shadow of death, chapeteo provides an insight into the way of life and survival in Guayaquil.

Figure 7 is a portrait of Snop 10, a member of theGobernantes del Norte(GDN, The North Governors) posing next to his own firearm which hints at his rank and seniority within his mob. Spray cans and weapons allude to a past when gangs took over Guayaquil. Nowadays, these groups are disarmed but maintain the tradition of chapeo in gatherings to evoke the culture of those days. The GDN tattoo on Snop's chest uses the skin as an extension of the sign and the signifier. Clearly, belonging to these groups involves a complex semantic system of representation and identity.

Pichação, ganchos, and chapeo: regional calligraphies

'Infelizmente a pichação

É um degrau pra criminalide

Começa a roubar, practicar um doze

Perigo para a sociedade'

MC Papo

This research aims to put into perspective the similarities, differences, and intersections between local, organic, and site-specific calligraphies and what I would call ‘pure’ graffiti. For this purpose, I will take into account two more such ‘regional calligraphies’: ganchos in Monterrey, Mexico, and pichação in Brazil. Showing their stylistic features and untangling the origins of their emergence, development, and projected futures is important and provides ground for future research. Such a systemic approach will allow for a greater understanding of these practices as archives of urban culture in Ecuador and South America at large. As Pedro Russi explains (1999: 20):

[…] graffiti can be considered as expressions of specific communities or individuals which are made with selected support and through which meanings are conveyed. They demarcate territories in space and time and represent the identity and recognitionof the interpreter (even when unableto decipher).

The point about identity is fundamental because chapeteo is both a calligraphic practice as well as a process of group identification. This is a trait that pertains to every type of graffiti, including pichação and ganchos. In this respect, LR of the ‘Z’ gang from Monterrey explained in a conversation I had with him that there is a solid sense of unity within the groups through the proliferation of identity-based graphics:

Ganchos and apañes, I believe, are influenced by the oldest gang members from the 1960s. Back then, there were already gangs here that started marking their territories by putting their names and nicknames on walls. At a later stage, in the ‘80s, people started doing the same but with more distorted yet still legible letters. It was only after that time that the barely legible apañes began to appear. In the 2000s they stopped calling them apañes and writers stopped doing signatures. Instead, we got used to seeing them as ganchos (hooks) and to call the practice ‘throwing hooks’, as the letters we would make had hook-like ornaments.

Typically, writers sought to generate distinctive features that could associate their graphic production with a territory or moment in time. Chapeo has been created even by adjusting the medium: writers would ‘operar las mechas’, i.e. deform the nozzles of the spray cans to achieve the desired effect according to their style. Figure 11 shows Snop 10 doing this.

In an article about ganchos in Monterrey Pablo Perez points out (2013: 2):

Gancheros, in turn, proudly claim to be unique, as anyone with even only a slight involvement in street art will confirm. Before the internet and shortly after the explosion of hip-hop, ganchos in Monterrey emerged. At that time, there was very little information about graffiti from other parts of the world, mostly in commercial films or music magazines. The absence of information allowed apañes to acquire their own shape: fluid movements, wide curves, obsessive geometry, symbolism, letters that don’t look like letters but like animals.

This description catches my attention because looking at the images shared by LR himself, aesthetically speaking ganchos has a striking resemblance to chapeteo. In fact, a careful analysis shows visual similarities between pichação, ganchos, and chapeteo. In their need to distinguish themselves from the aesthetics of graffiti, these three forms of writing developed during the same time span, i.e. between the ‘80s and 2000s. This need to differentiate from pure graffiti provides proof that more recent generations of urban writers have pursued singularity. In both form and substance, Brazilian, Mexican, and Ecuadorian youths had the desire to explore a calligraphy of their own. In geographical terms, these types of practices manifest themselves in the north and south of the Americas, as well as in the middle, which is more or less where Ecuador is situated. These are geographic poles which, in terms of their sociopolitical, economic, and cultural circumstances, narrate their own history and contextual ‘archeology’.

As mentioned before, chapeteo bears a direct relation to migration, family disintegration, and economic circumstances (the devaluation of the Ecuadorian currency). The story repeats itself for both ganchos and pichação: desperate and lonely youths urging for a sense of belonging and willing to take over the city. For its part, pichação configures a space of graphic resistance and social complaint around the profound inequalities of Brazilian society. It is a process of cryptic communication from that side of the city which is defined by marginalisation and precariousness, similar to the beginnings of graffiti in New York. In this context Russi (1999: 23) discusses strategies of meaning-making based on specific practices and rules that result in urban appropriations. Pichação, ganchos, and chapeo show commonalities with pure graffiti in terms of strategies, illegality, ephemerality, and anonymity, but move away from the traditional culture of tagging and bombing in terms of form.

The endeavour to be different, to have an own identity and autonomous models of representation comes in response to systems of oppression not dissimilar from the one experienced in previous decades by minorities in the ghettos of New York. This context was a breeding ground for original styles, which has led to a form of production outside the system, a struggle against so-called high culture and a watershed with respect to hegemonic art. Marco Tulio Pedroza (2018: 3), a Mexican scholar specialised in pichação culture, puts it like this:

Pichação is a style of graffiti exclusive to Brazil, an alternative culture of urban writing based on the execution of signatures throughout the whole city and beyond. The pixadores associate pichação with signing, mark making, staining, but mainly with protest and transgression. Pichação transgresses the appearance of most public spaces all over Brazil. Its aesthetic flies in the face of the hegemonic aesthetic, which implies excessive tagging of anything pixadores find in their path, hence this practice is criminalised.

On the streets, gancheros, pixadores, and chapeteadores leave distinctive and semantic imprints and codes legible only to their peers. A unique system of communication that liberates them and separates them from the rest. This visual and representational production grants them a sense of unique individuality. Their search to generate parallel systems to the one established through territorial and nominal mark marking, could be recognised as an inherent condition to these three native expressions, as well as to pure graffiti. In the words of the Mexican academic and expert on this subject Dr. Marco Tulio Pedroza (2018: 3):

Pichação could be defined almost in the same terms as tagging, as its conditions of production are exclusively illegal. As is the case with other graffiti writers, pixadores use a tag in the form of a nickname, alias, or pseudonym which they treat as though it were their real name. Tags become a mechanism that grants them a public identity, which guarantees anonymity towards everyone outside of their culture. Simultaneously, writers gain recognition for their work inside of the culture, which can be expressed in different ways: fame, prestige, admiration, or respect.

In this context, the analysis of urban writing offers various nuances for approaching these calligraphic manifestations in public space. The aim of cultural studies is to understand that these are true ways of inhabiting the city and creating unique relational systems, as they circulate parallel alphabets and complex systems of communication that distinguish the writers from the masses. In this way, the tagging of the first generations of writers is intimately related to these other forms of calligraphic production. Nevertheless, the search for originality is a constant factor as Castillo and Naranjo (2019: 2) point out:

Graffiti and pichação both have the same roots, as both are considered illegal and use the same medium (the city) and the same materials (spray paint and paint). Both have emerged as a response from young people living in the outskirts to the exclusion they have suffered in the cities.

The influence from graffiti is undeniable, but there are regional phenomena worthy of study. These disregarded calligraphic forms constitute the voice of several generations of people marginalised, criminalised, and submerged in the peripheries of major cities. Pichação, ganchos, and chapeo represent a fresh niche of study for those who have made the streets their path in academia.

Testimonies

This part of the paper features a selection of interviews held with representatives of the chapeo scene: Pipo 12, Yinsu 96, Snop 10, Fantasma 77, and Caos 30.

Pipo 12

How did chapeteo come about in Guayaquil and where did the style of writing come from?

To be honest, everything related to chapeteo here in Guayaquil is directly connected to the gangs. The roots of chapeteo, the very first writings, were made by Los Contras. People began choosing their tag, name, nickname, and pseudonyms. Numbers attached to names depended on where you used to live. I am Pipo 12 [of New People] because that's the busline that passed by my house. We were all in different sectors [neighbourhoods], we would go out and represent ourselves. The verb is chapetear. The typography is 100% from here, you won’t find these letters anywhere else. Once it started, the style kept on mutating and it was perfected until it became what it is today. People would tune it up and each sector would come up with its own alphabets. In the south of the city it was more angular and aesthetic, in other places it was spikier. In one line you could find the chapeteo of 15 different guys.

How would you organise going out to tag?

Usually after classes, people would be ready with their cans. Mates would come over and operaban la mecha: make the hole in the nozzle of the spray can bigger with a razor blade or needle. This made the spray come out faster and in a wider and more fluid way. We would call this a conaso. Then one of us would stand on the corner to alert the others in case cops would arrive on the scene. Each one alerts the other. Another one would yell which chapas to paint. Sometimes there were eight to 15 of us.

What were the objectives of chapeteo?

In one way or another, territories got marked and people would get to know each other on the streets. For example, I would go to the intersection of 38 and Portete, I would find a cool wall and tag Pipo 12, then others would come and do the same. One was always on the lookout for the most eye-catching and prominent walls. It was about claiming those walls, even if our tags would get erased. My group would come and tag on one side, if someone would then tag over me, we had to go find them.

Yinsu 96

Can you tell us about your initiation into chapeteo?

I started off in chapeteo simply by reading what was there. The writings would grasp my attention, and even if I couldn’t understand them I wanted to know what they were about and why they were made. I was raised in Bastión Popular, a rather dangerous area according to some. At the age of 13, I would do my first doodles with crayons, charcoal, and markers. In school I would play ball games but that was not what I was truly interested in. Some dude from my neighbourhood, who was already in fifth grade, was part of Los Contras 96, a gang from around here. They would set up reuniones (meetings) and they would try you. Those were my first experiences. There sure was theft and that kind of stuff, that didn’t really go down well with me. Little by little I would open up more, around that time my dad − may he rest in peace − lived in the south, in Guasmo Central. Back then everyone who painted was a gang member, there were all kinds of people, good people, bad people.

How did the chapeteocalligraphy develop?

Around those days there were ‘Los Contras’, ‘New People’, ‘La Marea Negra’, which could be identified by the type of calligraphy they would use: a spiky, square or round typeface. Others had a more stylised way of writing. You wouldn’t find the same thing all the time, there were different details in each letter. There were types of letters, around 15 different types of the letter A for example, and you could mix and match styles easily. Most of chapeteadores, were in the colleges called Vicente Rocafuerte and Aguirre Abad. We would go to the hardware stores and steal the cans of paint. We would go through the hassle of simply taking the paint in the extreme event there would be none of it left.

Which gang did you belong to?

When I became a ‘New People’ member in 1997-1998 I was still a college kid, I lived with my dad in the sector called Guasmo. I got to meet Pista 76 and Pluma 73. I don’t remember well how we became friends but we talked and I told them: ‘I want to learn your thing, I want to be with New People’. I said to them I was familiar with tagging and that they should give me a chance. I first met with three of them, then 10, 15, 20. I don’t mean to exaggerate but at one point there were around 150 people or more. We gathered people from Pascuales, del Fortín, de la Prosperina, Bastión, de la Florida, just imagine all these ‘Christians’ tagging all over the city. Soon enough, there was no more room left to tag. By that point, those who were painting risked being fined a thousand dollars. There were bans on graffiti. Every day in the south of town there would be around 12 or 13 people out there painting. There was no fixed time, we did it whenever we wanted, even in broad daylight. The painting would start on the busses we were riding. If I would take the bus to the city centre, it would be tagged all over by the time it got there. We only cared about one thing: tagging, tagging, tagging. What mattered was whoever did it fastest or best, that was the coolest person. The riskiest thing I did was painting near the premises of the judicial police. One time I got detained because they caught me tagging. I was locked up for three days and my family kept asking why I would do such a thing; they were against me. Among the good things were the friendships. Some of those people are still alive.

What kind of music would chapeadores listen to and what would they wear?

The fashion in those days was flannels, baggy trousers, and yellow Caterpillar boots. The nightclubs were Forever, Display, La Cocodrilo, El Latin Palace, El Mundo Frío, El Latin Palace and La Terraza. In any dance party you would find chaperos – you either bumped into your mates or made new friends. The chaperos all went to boys’ schools, their ages ranged between 14 and 22. Naturally, once we were done in the night clubs, we would go out to go paint. Every time, on our way out of Dos Pistas or Pley, we would go hit the walls. Around that time we listened to Spanish rap. Out came the Panamanian reggae by a group called Cuentos de la Cripta. House music was a must in the nightclubs. There were some dancing battles too. But what we all cared about was tagging! Sometimes the night would end up in a fight.

Snop 10

Which gang did you belong to?

‘Gobernantes del Norte’, which was formed in 1997. Before that, I was part of ‘Chemise’, which started in 1972, long before Los Contras and New People. In '72, when a new era began amidst the repressive government of León Febres Cordero, we started getting together for self-defence. If someone robbed or killed a chapeteo, his blood would be used on the wall. In 1987, the first graffiti appeared with the new generation. By the end of the '80s and beginning of the ‘90s there were more than 300 gangs in Guayaquil.

How would you describe those days of chapeteo?

The one who would tag the most would be the most respected. The one who would sneak into someone else's zone and paint would earn even more respect. Los Contras and New People joined forces to push out GDN, which was notorious for being the most dangerous gang. In 2009 we made a peace agreement. Women became part of the gangs: Cris 81, Diva 10, la Girla, la Rose, la Nena. In order for women to join a gang, they had to sleep with the six most senior members, the bosses. The gang came from the Modelo neighbourhood, La Muerte was based in Simón Bolívar. I first roamed the streets when I was eight years old.

Why were gangs in Guayaquil formed?

A lack of love, we all have the same story. Moms acting as both mom and dad. Divorce, stepfathers, stepmothers. We would go out on the streets searching for the attention we couldn’t find at home. In the gang we would find all the love we needed, food, someone saying ‘hello, how are you?’. If we didn’t have what we needed, we would go out to steal. We would go to the hardware stores, ask for two or three spray cans and then hit the streets. The gang would offer you protection and support just for staying loyal to their organisation. They would give us weapons, everything. There were squads for weapons, for tagging, and for stealing.

What was the boldest thing you did?

We tagged signage, buildings, police cars, the police station and even an airplane. Mayor Jaime Nebot was looking for me for around two years, he was sick of me, I had been tagging everything everywhere. There was a list of the most wanted persons for tagging and I was first on that list. Chapeteo was a form of communication intended not to be understood by anyone. We would keep modifying the letters to make sure they could not be read. If we would find someone with the same tag we had to eliminate them.

Fantasma 77

Please tell us about your experience with chapeteo.

I joined Los Contras in 1991 when I was 12, my touchstones were Gota 42, Suburvio, and Los Coquis, who were just starting with chapeteo. They were the first to develop the unique style of writing with jagged lines by the river bank. Then Gota 42 started redesigning those letters. Students that were being expelled from Vicente Rocafuerte spread all over Guayaquil. By 1991, the city was fully covered with tags. Nowadays I don’t tag anymore, I stopped in 1999 though briefly returned to the practice in 2010–2012 when I activated the last Contras generation − we were the bomb! In 2011 some old guard chapeteros from the Contras, New People, and GDN – Star 85, Buffon 27, Stan 27, and myself − got back together. That day we tagged the police barracks of Modelo all over and got arrested for it. Right on the first grand reunion Las Letras Pandilleras got out of the suburbs while the Contras also spiced things up. Papi 77 was there too, the ‘Good Girl's Daddy’ owning the streets. Every time we get together we listen to boricua house music, industrial techno to refresh our memories.

Caos30

Could you tell us about your experience with chapeteo?

I started gang writing with the ‘Rebel People’ from Durán in 2001 when I was 12. I dropped out of that group because there were too many drugs, stealing and stuff like that. The initiation rituals included doing small robberies. When I got back to Guayaquil to live in the southern central zone by Capwell Stadium, I would find more and more gang writing. I would look at the writing of GDN and NPE. I was most interested in the tags by GDN because of their use of space. I belong to the fourth generation of chapeadores that moved over to graffiti. I used to paint in the areas around Portete, Centro, and 25 de Julio streets. One of the most meaningful anecdotes of my life was when Bufon 27, Made, and I sneaked into the airport to paint, and we got chased by the police. They caught me and stole everything I had. They spray painted me with my own cans and took a bunch of photos. I was put in pretrial detention. When I got out I searched for the cops who did this to me. I filed two complaints against them. When I finally found one of them I asked him to give me back my stuff and to help me do graffiti. Ever since he has been helping me.

Conclusions

1. Chapeo, also known by the common people and the protagonists of this practice as chapeteo, is a calligraphy style unique to the city of Guayaquil. The development of this type of writing became popular among youths in the late 1980s, early ‘90s. It functioned as a sort of street ritual based on leaving traces and marks all over the city, and consisted of the creation of alphabets that explored the forms of each letter, with up to 12 different typologies for each vowel or consonant. The outline of each letter depended on the geographic location of its creator. Round, square, or spiky were the distinctive basic shapes depending on the neighbourhoods and zones of the chapeador. This is of major importance as we deal with the construction of alphabets parallel to established ones. The express purpose was to create a complex process of literacy only gang members would have access to. It concerns an endemic form of communication created specifically by and for street gangs. Cryptic messages comprised mainly the names of gangs coupled with a number representing specific cells or derivative groups. The most represented gang was Contras 666.

2. At the outset,chapeo was oriented towards tagging on behalf of the collective, i.e. tagging the name of the group or gang, for example ‘Contras’, ‘New People’, or ‘Marea Negra’. Chapeo gangs were formed by multiple anonymous presences that all adopted the group's name. It is significant to highlight the connotation of collectivity of chapeo in comparison to the more traditional, individual ways of making oneself notorious with a spray can, which stems from the New York City graffiti practice (Castleman, 1995 [2012]). Based on this, I would not consider that the practice of chapeo, especially in its first phase, could be equated to tagging, as there was a sense of the collective present at all time, while the act of tagging is personal. As things progressed in the second phase of chapeo, the number of the bus line every individual gang member would use to go home was added to the chapa (tag). Subsequently, writers would also include their own nicknames and develop abbreviations and synthesising strategies for the names of their groups. For example, a member of New People would write: ‘Pipo12 NP’. Fully understanding these abbreviations – which at times seemed to morph into complex formulae − demands careful study.

3. Another distinguishing feature of those dedicated to chapeo was that of truly acting as a group. It is part of gang practice to walk in groups of at least five, ten, or 15 people tagging across the city. The interviewees mention that they would roam the streets together even in broad daylight, in contrast to their much more discreet peers in other parts of the world (Castleman, 1995 [2012]; De Diego, 2000; Figueroa, 2014). This modus operandi, however, did entail assigning two members of the gang to act as camapanas (bells) at both ends of a street to warn in case of approaching police or residents. In addition, there would be someone acting as ‘speaker’, calling out loud the names that would get inscribed in the collective tagline. Finally, there were obviously those dedicated to actually performing the complex calligraphy on the walls. These writers had in-depth knowledge of the alphabet in its various forms and were savvy with regard to three aspects: the calligraphic style of the gang, the mark making in relation to the neighbourhood, and the numbering of the specific cells. Besides being a genre of graffiti, chapeo thus also comes with a particular collective methodology in terms of execution.

4. Chapeo constitutes a graphic form that continues to shed light on the ways in which at least three generations of youngsters (from the ‘80s, ‘90s, and 2000s) inhabited the city – youngsters who, through gang conformation, tried to resist the transition to clans and ‘nations’ such Latin Kings and Ñetas. These higher-ranking associations managed to disassemble the native gangs of the city, polarising the initial youth groups into two camps. Clans and nations are associations with more complex and sectarian organisational and operational forms. In the words of activist Nelsa Curbelo (2004: 5):

They are larger and more organised youth groups that obey a chain of command based on seniority and merit. They have a minimum of one hundred members and are divided into cells according to the laws of the streets. They hold a pyramidal, hierarchical structure very similar to that of the military.

In the midst of the establishment of these new street customs, chapeo was substituted by the demand for more elaborate graphics such as graffiti. For their part, both Latin Kings and Ñetas were looking for more legible forms and a symbolic presence which the complex chapeo could not provide. More accessible letters, symbols, and graphics were needed to announce to Guayaquil that these new nations were here to stay. Along with this need for visibility, stones were exchanged for weapons and dance wars were replaced by turf wars in the fight over domination of the territory. While aggression and quarrels were already a part of life in the gangs, this was exacerbated by the advent of the nations and clans. Excessive violence attributed to this urban phenomenon took on even more extreme forms with the arrival of second or third generation Ecuadorian migrants who had returned from countries like Spain, Italy, and the United States. In chronological terms, the decay of chapeo began in the late ‘90s and early 2000s as a result of these new associative presences in the city.

5. Another reason for the almost total extinction of chapeo was police control and a series of municipal regulations and prohibitions, which went so far as to impose heavy fines. These restraints affected the no longer young gang members who in many cases chose to become part of the nations. Even if many of them did not agree with this transition because of the violence and great number of deaths, stepping away from the gangs altogether would have meant having to walk alone. Threatened by the new associations, a clamp down on crime by the police and the law as well as terrible family situations, chapeadores faced an untenable situation. The local government implemented a security plan called ‘Más Seguridad’ (more security), which was intended to regulate any type of activity that could generate chaos or violence between citizens, many of whom supported the initiative (Allan, 2010).

6. Today, at least three decades have passed since the first testimonies of the first chapeo remnants. In recent years, some gang members have founded graffiti crews. Among those who have switched from chapeo to graffiti or even street art, are Pipo 12, Climax 106, Yimbo, Yinsu 96, Smock 96, Plomo 76, and Pley. Gatherings of these crews are more like family reunions and nostalgia for the youthful days of gangsterism remains. New People even evolved into a registered civil society organisation that cooperates with municipal institutions, participating directly in festivals and projects oriented towards ornamentation and tourism in Guayaquil. Despite this epilogue, that has brought normalisation and adulthood to the protagonist writers of a time gone by, there is always the possibility of going out to chapear with friends fueled by the remembrance of the glory days.

The analysis of the peculiarities of chapeo highlighted in this paper has contributed to understanding this major form of cultural expression typical of youth associations in Guayaquil. It is a style whose historical value transcends the spaces occupied by morality and decency. The once omnipresent phenomenon ofchapeo articulates memories and has constituted an archive of images and stories from the underground, an archive of those who made out of the streets a battleground and a blank page to write their alphabets. Chapeo will always be more than mere gang writing, it is the graphic testimony of an historical epoch of the city of Guayaquil.

María Fernanda López Jaramillo is an Ecuadorian professor, researcher, and curator. She has been devoted to street art processes at a regional level for more than a decade and has specialised in the management of projects focused on production, research, circulation, and pedagogies for different communities. She sustains an active line of research which has resulted in two platforms called Emergencias Curatoriales (Curatorial Emergencies) and Vandalismo Intelectual (Intellectual Vandalism), as well as lectures in the Netherlands, Germany, England, Peru, Mexico, Cuba and Ecuador. Among other projects, López Jaramillo has produced and curated Cartografías Paganas (Pagan Mapping), MAAC – the First Binational Urban Art Exhibition in Ecuador and Colombia in 2019 –, as well as a university project called Arte, Mujeres y Espacio Público (Art, Women, and Public Space) in Ecuador and Mexico. López Jaramillo is currently head professor of the Management and Politics of Culture and Urban Art courses at the Guayaquil University of the Arts, professor of the Contemporary Curatorial Processes Course at the Master's Degree on Arts Management at that same university, Professor of Cultural Legislation and Cultural Policies in the Master's Degree on Cultural Management at the Politecnica Salesiana University (Guayaquil) and Head Professor of the Urban Art Certification in the FAD faculty at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

- 1

Anecdote from the streets of Panamá & Junín in the downtown area of Guayaquil in December 2018. Fantasma77 is an old guard (second generation) chapeador part of the Los Contras gang. In the streets it is well known he is a pioneer of this type of territorial mark making. After this first encounter we were able to chat with him.

- 2

A phrase from one of many conversations held with Plomo76, a leading character of the Guayaquil graffiti movement. Plomo is a writer, tagger, and urban artist with whom I have been in touch since 2012. He is part of the third generation of chapeadores and a key informer of this research and writing.

- 3

In terms of methodology, this paper is based on three constitutive elements:

1) he process of inquiry in primary sources through direct interviews with six urban writers, initiated in the tradition of chapeteo plus a ganchero from Monterrey, Mexico. This is done with the purpose of establishing similarities, differences, and intersections in these different practices of urban calligraphy. In writing this paper I will use chapeo and chapeteo interchangeably. Chapeo is the internal gang designation around this practice, while chapeteo is the common form that refers to this phenomenon from a collective standpoint. In this context, the participation of interviewees like Plomo 76, Yinsu 96, Pipo 12, Snop 10, Fantasma 77, and Caos 30 has been key. Their ages range between 28 and 39 and all of them currently live in Guayaquil. They still occasionally keep up with the practice. In regard to the Mexican contributor identified as LP from the Z collective in Monterrey, he is 40 years old and in ways similar to that of his counterparts in Ecuador, he still goes out to produce his ganchos every now and then. The contributions of the interviewees are crucial for this research as they represent multiple generations that have witnessed foundational actions of this genre. Their involvement with this practice began at an early age when they were around 8–13. It must be mentioned that other informers of past generations migrated to different places such as Spain, Italy, or the U.S. in search of better days. Others left the streets and preferred to remain silent about this activity while the most unfortunate lost their lives during the peak of gang wars in Guayaquil. While in the case of Mexico it turned out to be vitalto dismantle the conditions of production of ganchos in order to understand the need of an individual identityin the development of a collective graph.

2) y fieldwork investigation allowed me to be present in all sorts of graffiti battles, collective painting, festivals, and encounters where many writers gather. On these occasions I had the opportunity of holding conversations with Caos, Made, Toga, Joe, Yimbo, Buffon, Nkay, Flama, Yimbo, Climax, and other members of the local crews who in some cases had nothing to do with chapeteo but pinpointed key actors, while others were somehow connected to the practice. This proximityto the graffiti movement allowed me to have a less skewed or moralist position towards chapeteo, a styleI embrace despite all of its negative implications which are merely outcomes of the system we inhabit. Additionally, my work as a researcher has brought forth connections especially in Mexico, a scene I feel very familiarised with, hence my closeness to LR from theZ collective in Monterrey.

3) se of secondary sources, i.e. bibliographical material about signature graffiti as a parallel conceptual reference (Castleman, 1995 [2012]; De Diego, 2000; Figueroa, 2014 & 2017; Gálvez & Figueroa, 2014) that allow to identify in chapeo a genuine exercise native to the city of Guayaquil. In additionto these sources, I have turned to the work ofLatin American authors specialising in subjects like pichação, such asDr. Marco Tulio Pedraza: researcher at the National School of Anthropologyand History in Mexico City.

- 4

I would like to thank Nelly César Marín for the translation of this article from Spanish to English and Damian Rosero for adapting the original Spanish text on the basis of the editing of the English by the journal's editorial team.

- 5

In the summer of the 1980 The Times Square Show was a group exhibition on the initiative of artists’ collaborative COLAB (Collaborative Projects Inc.). It saw more than 100 young artists hard at work experimenting and opposing the art establishment in punk-like rebellion. Open 24 hours a day, the show took place in a vacant six-storey massage parlour at Times Square, New York.

- 6

‘Unfortunately pichação is a step towards criminality, you start stealing, practicing a 12 [a graffiti style], become a danger to society.’ From MC Papo's 2007 song ‘Eu Pixava Sim’: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MJi4TCMxOMY.

Alegría, A. & Patricio, H. (2010) Regeneración urbana y exclusión social en la ciudad de Guayaquil. Quito: FLACSO – Sede Ecuador.

Cantillo, V. & Naranjo, F. (2019) ‘El pixação como medio de reapropiación del espacio en un sistema complejo’. XIII Jornadas de Sociología. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires.

Castleman, C. (2012) Getting up: Hacerse ver el graffiti metropolitano en Nueva York. Madrid: Capitán Swing Libros.

Curbelo, N. (2004) ‘Las Expresiones Culturales Como Agentes De Cambio en grupos Juveniles Violentos’ [Online] Accessed January 20, 2021. https://studylib.es/doc/5631122/las-expresiones-culturales-como-agentes-de-cambio.

De Diego, J. (2000) Graffiti, la palabra y la imagen. Barcelona: Los libros de la frontera.

Figueroa, F. (2014) El graffiti de firma. Madrid: Colección Textos.

Rivera Lucin, B. (2016) Seguridad Ciudadana e Iniciativas Culturales En Guayaquil, En El Período 2000–2014. Quito: Universidad del Postgrado del Estado.

Pedroza Amarillas, M. T. (2018) ‘Cultura graffitera brasileña’. Revista Digital Universitaria (RDU), 19(2): 19.

Perez, P. (2013) ‘Gancheros somos en el apañe andamos’. Sexenio, August 21, 2013. [Online] Accessed January 20, 2021. http://www.sexenio.com.mx/nuevoleon/articulo.php?id=21124.

Serrano, F. G (2013) ‘Geografía de la exclusión y negación ciudadana: el pueblo afrodescendiente de la ciudad de Guayaquil, Ecuador’ in: Grimson, A. & Bidaseca, K. (ed.) (2013) Hegemonía cultural y políticas de la diferencia. Buenos Aires: Clacso: 201–222.