The year 2020 highlighted intricate questions about the role, (re)mediation processes, and (im)materialities of graffiti and street art. Through changing levels of lockdowns and restrictions, and through new social realities worldwide, the coronavirus pandemic reshaped the positions of arts and cultural productions. While many of those engaged in the arts and cultural sectors had to cope with new requirements in order to be able to keep on working and be accessible, new opportunities also emerged, especially in and by the virtual spheres. At the same time, these conditions had an impact also on the possibilities of arts to enable people to manage and reflect on their everyday circumstances. A case in point is disCONNECT, an urban art exhibition co-organised by Schoeni Projects and HKwalls, first in London (July 24 – August 24, 2020) and then in a locally adapted form in Hong Kong (October 11 – November 29, 2020), complemented by permanently available online displays. By disrupting the usual paradigms of the art world (both gallery and street art scenes), the main aim of the organisers was to create a novel approach that would enhance togetherness and collaboration, and inspire conversations.

In globally precarious conditions, the disCONNECT exhibition indicated not only the growing importance of arts for bringing people together from all walks of life and across artistic styles. In terms of contemporary arts in general, it also contributed to an unprecedented paradigm shift towards remote working and viewing practices across cultural contexts. This hybrid, multi-site endeavour with virtual exhibitions raises new questions within the long-lasting discussion on if, how, and where graffiti and street art – and/or manifestations based on these practices – can be exhibited and documented. What are the defining features of ‘authenticity’, and how do the protagonists re-experiment with a host of artistic practices in order to expand the field to interactive immersion? It therefore also repositions research on graffiti, street art, and urban art at the intersection of the immersiveness of virtual reality and virtual arts (Bolter & Grusin, 1999; Grau, 2003; Popper, 2007), the importance of (re)mediation processes for sense- and memory-making (Bolter & Grusin, 1999; Erll and Rigney, 2009), and the growing interest in augmented reality in arts (Geroimenko, 2014). Through close analysis of processes and artworks, and by investigating the experiences and perceptions of organisers, artists, and audiences, I distinguish what kind of (dis)connections, interactions, and layers of immersiveness the exhibition project made evident through the ephemerality of the tangible art exhibitions and the permanency of the intangible ones online. Even though it is commonly acknowledged that a virtual art exhibition cannot (yet) provide comparable sensorial experiences, nor create similar affective atmospheres as physical on-site art exhibitions can, new technological advancements nonetheless bear increasing potential to build towards enhanced immersiveness and interactions in and between online shows.

Readjusting arts and streets due to the COVID-19 pandemic

Opening during the COVID-19 pandemic, disCONNECT not only adapts to adhere to restrictions imposed by the pandemic, rethinking creative and physical constraints due to the current global crisis, but also prompts reflection on the psychological reactions toward the pandemic as well as the role of technology. (press release of disCONNECT Hong Kong)

Since the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020, a great many artists have started to engage with a variety of graffiti and street art practices for communal, didactic, and sociopolitical purposes. Murals of figures wearing facemasks and raising awareness of public health security have gained the most public attention, but they represent only one visual form and intention among a multitude of related motifs and approaches. From stencils and installations to masked-up public statues, all such creative takes on the pandemic on the streets have communicated shared mixed feelings of concern, criticism, and, to a growing extent, gratitude to the front-liners’ tenacity. Besides their unsolicited manifestations, artists are also collaborating with local communities, officials, and international programmes.

The need for varied forms of art in public spaces has been heightened by the lack of adequate access to museums, concerts, and other indoor events. Such aspirations were further enhanced by the economic challenges and existential threats that hit independent art organisations and artists especially hard. Where possible, audiences and artists alike moved their artistic practices to public spaces, but in curfew circumstances, other options were called for and fed the demand for online exhibitions and services. As has often been the case during societal crises, art and artists not only respond to and reflect on the existing hardships, but also seek new strategies for mitigating them.

Both the plans and the practices for the disCONNECT exhibition project had to be similarly readjusted and gradually implemented in relation to the local regulations during 2020. The organisers originally wanted to invite an international group of graffiti and street artists to take over the Schoeni Projects’ future space in London – a Victorian townhouse in South West London – before its renovation. This inaugural exhibition was planned to take place in late April 2020. While most scheduled art events and exhibitions were simply cancelled or closed, HKwalls and Schoeni Projects felt that they needed to find a way to continue regardless of the perilous circumstances and to develop a cross-continental hybrid exhibition directly addressing the realities of and reactions to the pandemic. As Nicole Schoeni elaborated before the opening: ‘You just have to stay positive. This is the new norm and there's no certainty when or if things will go back to what we are used to. […] We have to reject the sense of loss of hope and instead, make some positive sense about the situation we are in and give it some meaning.’

With international travel restrictions in place, my plans to see the exhibition in person, at least in Hong Kong, gradually evaporated too. Yet, the necessity to rely on remote research methods, such as online communication and digital information, in turn enhanced my understanding of the artists' and organisers' experiences about new forms of cooperation. As such, this study was also transformed into a personal endeavour to examine whether and to what extent this kind of hybrid exhibition could be examined. How could I − eager to see and analyse art and, in particular, to witness how it resonates with the site − adjust my working methods to these new realities? Instead of urban ethnography and close analysis of the artworks in situ, this paper therefore tests novel research paradigms in practice, resonating more with the exhibition project itself.

Paying close attention to health security and safety, the curation of the London exhibition for the end of the summer relied on innovative remote working methods and collaborations. Detailed information and abundant visual materials of the house, the rooms, and the utensils available for the artists to choose from were sent to the artists to facilitate their creation processes. Four artists based in London – Mr. Cenz, Aida Wilde, Alex Fakso, and David Bray – took turns creating their artworks in the townhouse, while other artists were occupied by the search for innovative remote working methods due to international travel restrictions. For instance, the house's original doors and curtains were sent to Vhils in Lisbon and Adam Neate in São Paolo respectively, to enable them to create directly on these objects, which were then returned to London and placed back into the townhouse. Likewise, Paris-based Zoer could not travel to London to set up his work, so local artists and assistants were needed to paste up his large-scale and meticulously detailed installation. Icy and Sot found a kitchen table in New York similar to the one in London and after carefully designing the plates and cutlery, they sent these across the pond to be installed on the original table in the exhibition space. Preparing and placing Isaac Cordal's miniature sculptures around the house and the garden relied on multidimensional communication between Cordal in Norway, his Bilbao-based studio, and the curatorial team. In Germany, the artistic duo of Herakut created their cardboard figurines in their studio and shipped them over to be installed. Yet, handwritten texts on the walls by a curatorial team member required projections and online video consultation with Hera in order to match the right style and rhythm. The final touch of playfulness in the room was created by small children who were invited to draw on the walls, which added another layer of interaction and collaboration in terms of shared agency.

The London exhibition was already an unprecedented international collaboration, but to transfer a selection of the artworks and set these up anew in Hong Kong for the second edition in November raised the translocal (re)mediation processes to a new level both in terms of logistics and curatorial practices. Four local artists, Kacey Wong, Jaffa Lam, Go Hung, and Wong Ting Fung, were invited to respond with their art and create further discussion about the pandemic and about how the related emotions and anxieties are to a large extent globally shared. Obviously, the exact same narrative and curatorial strategy would not be feasible because of the different layouts and features of the physical sites – a British townhouse from the 1850s versus a restored Hong Kong tenement building from the 1950s and an annexed pop-up space in a shopping mall close by. Relying on both professionals and volunteers to take care of a vast array of responsibilities, altogether around 215 to 220 people in ten countries took part in this cross-cultural project. Taking into consideration how much of the organisational and curatorial communication relied on technological interfaces, disCONNECT attests to the possibility of international collaboration regardless of restricted circumstances.

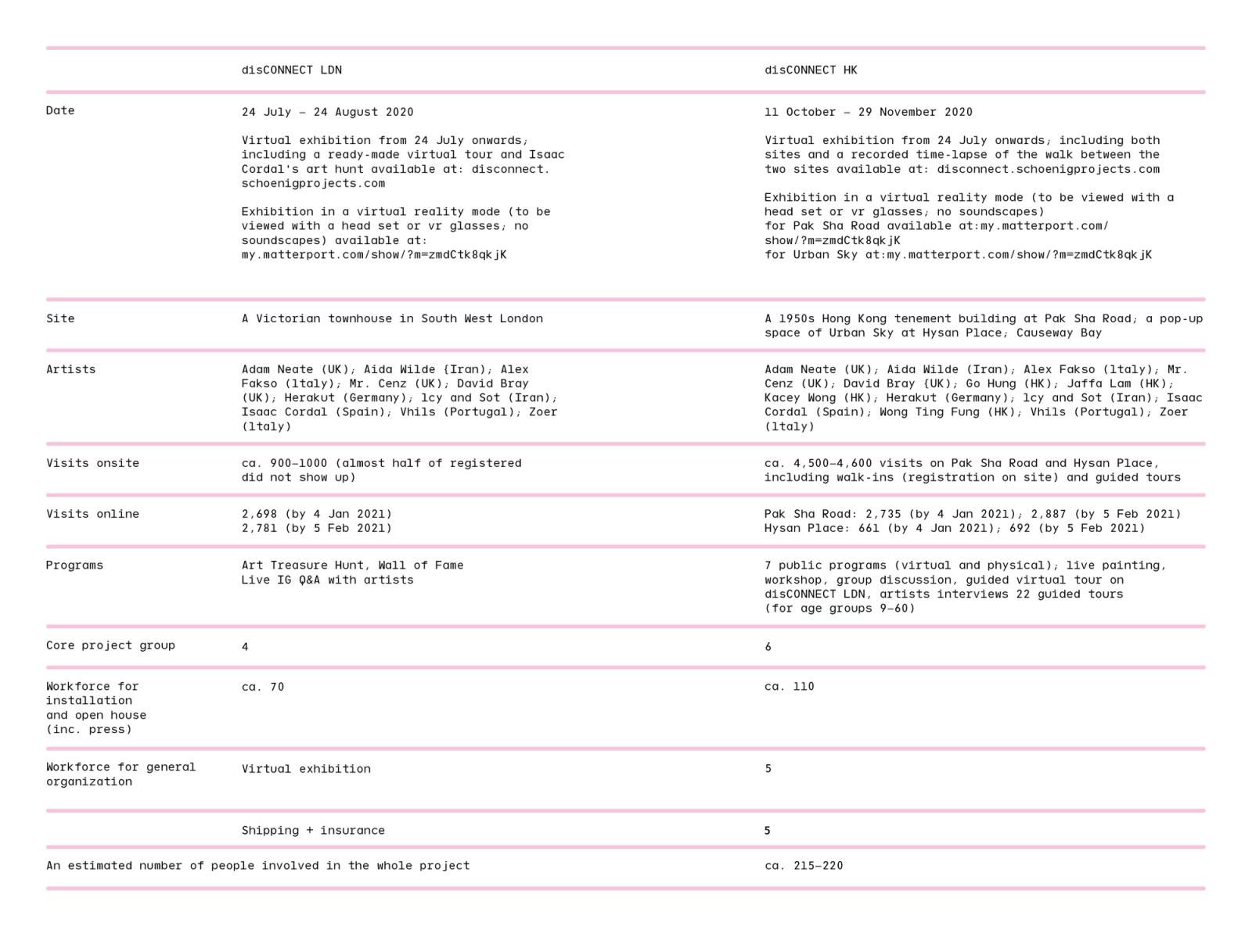

Adding to these practical challenges of transfer during the pandemic are the dissimilar habits of visiting, viewing, and appreciating arts in these two rather different cultural contexts. For instance, visiting exhibitions in museums and especially shows in art galleries is less common in Hong Kong than it is in London. Moreover, the multilayered history of graffiti and street art has gained more media coverage and appreciation in the 21st century in the UK. For Nicole Schoeni, one of the defining features of street art is its accessibility to the general public, as it is neither displayed in white cubes nor intended for art enthusiasts only. Together with HKwalls' managing director Maria Wong and co-founder Jason Dembski, Schoeni was keen to demonstrate the diversity of street art in non-gallery-spaces in order to question the internal hierarchies of contemporary arts that still confine graffiti and street artists into less valued categories. Keeping the innovativeness and quality of art as the primary criteria, the curatorial team had set its sights on a rich mix of emerging and more established local and international artists with varying approaches and methods engaging with public spaces, publicness, and communities. In spite of the numerous technical challenges, the notions of ‘publicness’ in art and how it can be enhanced through online interfaces, not limited to social media, gained additional dimensions: the online exhibitions featured high-resolution imagery and specific soundscapes, while the virtual reality manifestation required a VR headset or glasses for viewing. This approach applied to all three exhibition sites (Figure 1). Before delving deeper into these multilayered interactions, interfaces, and immersions of the on-site and online exhibitions, it is worthwhile to examine the prevailing affordances of and alignments between digitalisation on the one hand and graffiti and street art on the other.

Digital resonance in and for graffiti and street art

The digital documentation and distribution of graffiti and street art through the internet towards the end of the 1990s had a major impact on artistic practices on the streets across continents. While such (re)mediation processes were – and still are – essential for enhancing translocal knowledge exchange, they are also to some extent prone to (un)intentional partial information, misrepresentations, and misreadings. In the 21st century, an increasing interest in improving the visibility and understanding of graffiti and street art practices worldwide has emerged among protagonists and researchers, leading to a flurry of online databases, platforms, and map applications. Curatorial aspects and permanent online preservation are increasingly emphasised by initiatives such as the Google Cultural Institute's Street Art Project. Launched in June 2014, this project relies on collaborative partnerships with graffiti, street art, and muralism communities around the globe. Yet, as Glaser (2018), among others, elaborates in detail, digital archiving projects are liable to multiple issues, including but not limited to platform politics, accessibility, incompleteness, and subjectivity.

These intricate questions of documentation and preservation, whether within or beyond the urban infrastructure (see also Bonadio, 2019), directly interrelate with broader critical discussions on the institutionalisation of graffiti and street art by galleries, museums, art markets, and street art festivals. The repercussions and prospects of (re)positioning and documenting graffiti and street art in an institutional space, and the ways in which processes of ‘translation’ depend on the medium and the site, can be analysed in detail from a variety of perspectives (see e.g. Di Giacomo, 2020; Hansen, 2018). Even if the first exhibitions were organised in New York by United Graffiti Artists already in the 1970s, the inquiries into representational politics are well grounded today – not least because of the new layers of (re)mediation added by virtual exhibitions.

Another major change that the (re)mediation processes have brought about is experimentation with digital practices in graffiti and street art, which, in turn, have established new interactions between (im)material forms of art both in tangible urban landscapes and intangible virtual realms. While various technological advances have been keenly experimented with in new media art especially since the late 1960s, it was not until the mid-1980s that digital interventions by contemporary artists such as Krzysztof Wodiczko emerged in the urban infrastructure. By adding multiple layers of signification which directly questioned the official narratives maintained by public art and spaces, his pioneering public projections revealed how ephemeral practices could disrupt the predominant power structures and aesthetic codes of the city. In the realms of graffiti and street art, similar advancements towards digital, virtual, or augmented features started to gain more interest around 2006–2008. Holograms, projections, laser beams, and virtual reality (VR) allowed for new modes of engagement with the urban environment and enhanced a multitude of intentions, from unauthorised urban hacking to commissioned spectacles. Some well-known examples include the GRL L.A.S.E.R. Tagging System developed by the Graffiti Research Lab, and INSA's hand-painted, animated street art, gif-iti. These have both also been introduced and employed in translocal collaborations in East Asian cities.

Inevitably, laser tagging and virtual bombing, together with projections and new manifestations made possible by augmented reality (AR) applications, question the prevailing understanding of graffiti and other creative interventions as destructive vandalism. Yet, their immateriality enables new takes on ‘virtual vandalism’ not limited to urban space and public artworks but happening also in art institutions and exhibitions. Even more importantly, these examples demonstrate the shared need for digital equipment as an inherent part of the processes of creation and perception. Such reliance on technology not only further complicates issues of ownership, accessibility, and visibility, but necessarily adds to the multilayered significations that these interventions create in and beyond the tangible (semi)public space. In this respect, the above examples of the Graffiti Research Lab and INSA indicate the rich variety of practices that have continued to strengthen the mutual dependence of the analogical and the virtual. Consequently, they closely resonate with the following, much-quoted words by Lev Manovich (2013: 15):

I think of software as a layer that permeates all areas of contemporary societies. Therefore, if we want to understand contemporary techniques of control, communication, representation, simulation, analysis, decision-making, memory, vision, writing, and interaction, our analysis cannot be complete until we consider this software layer. Which means that all disciplines which deal with contemporary society and culture − architecture, design, art criticism, sociology, political science, art history, media studies, science and technology studies, and all others − need to account for the role of software and its effects in whatever subjects they investigate.

Understandably, the ‘real’ site-responsive, unauthorised interventions created manually in-situ in physical urban infrastructure remain the valued cornerstone for many protagonists. Such interventions are the key defining factor of ‘authenticity’ and ‘keeping-it-real’, not only for old-school graffiti writers but also for the majority of street artists whose work leans on the nuanced interconnectedness with the site and the materials. Hence, Manovich's perceptions on the ubiquity of software does not infiltrate all the graffiti and street art practices in the tangible urban environments to the same degree. Yet, besides actual artisticand creative practices, other related areas − from the design and planning of activities to documentation and supervision − are subjected to information and communication technologies (ICT) and henceforth to datafication with unpredictable consequences. This in turn is reshaping the field and highlights the need for further studies in the future.

Throughout my research across eighteen cities in East and Southeast Asia during the past decade, it has indeed become evident that a growing variety of artistic and creative practices in urban public spaces are actively using digital devices and applications in order to find ways to engage and interact with different layers of (sur)reality. My findings therefore further confirm Gwilt's (2014: 189–190) perceptions that connecting augmented reality with graffiti and street art ‘provides us with a complex socially and technologically encoded interface that has the potential to combine the first-hand experience of public space, digital media and creative practice in a hybrid composition’. At the same time, AR applications enable activists to explore innovative ways of disseminating information, enhancing participation, and circumventing censorship (see, e.g. Skwarek, 2014). Forms of ‘augmented urbanism’ with mixed reality tools bear the potential to activate the city by enhancing community engagement through less-privileged neighbourhoods too (Wilkins & Stiff 2019). In the same vein, amplified knowledge exchange could also increase AR applications’ efficacy in building reciprocal communication in graffiti and street art with new methods of increased site-responsiveness in the urban environment and beyond.

In light of these intersecting trajectories, the disCONNECT exhibition highlights new potentialities for interconnectedness by providing both on-site and online displays (see Figure 2). Digitalisation practices inevitably add new layers of emphasis on ephemerality both in the tangible environments of streets and in temporary exhibitions indoors. Simultaneously, the employment of new digital applications enhances the works' permanence and broader visibility in intangible, virtual realities. This rewarding contradiction provides innovative ground for both sense- and memory-making processes. But can a virtual exhibition offer added value to a physical exhibition regardless of its limited sensory experiences and affectiveness? Given that the detailed, high-resolution virtual displays of the artworks, their physical surroundings, and work-specific soundscapes all contribute towards an immersive experience, disCONNECT also provided new challenges and prospects for creating, perceiving, and researching graffiti and street art.

Online / On-site:new realms of interactive immersiveness

Virtual reality does in fact begin with the assumption that vision, like the self, is disembodied. Nonetheless, the goal of virtual reality is not rational certainty, but instead the ability of the individual to empathize through imagining. […] The technique of visual immersion distinguishes virtual reality from the classic transparent medium, linear-perspective painting. (Bolter & Grusin, 1999: 251)

Virtual reality, by definition, relies much on the faculty of imagination and brings forth strategies of visual and audible immersion. However, as Grau (2002), among others, elaborates, image spaces for creating illusions based on varied immersion strategies have been commonly used in visual arts even before digital affordances. Understanding immersion from the perspective of a transmedia continuum enables us to perceive how common the aspiration has been – and still is – for making spaces reaching beyond everyday realities, regardless of the differences in contemporary methods and technologies. Especially in interactive, computer-aided real-time new media art, borrowing Grau's (2002: 8–9) words, ‘[…] interactivity and virtuality call into question the distinction between author and observer as well as the status of a work of art and the function of the exhibitions’. Still, it is important to consider that since the 1970s, interactive participation in contemporary arts has found new strands to redefine − through material and tangible forms − the interrelations between artist(s) and audience(s) too.

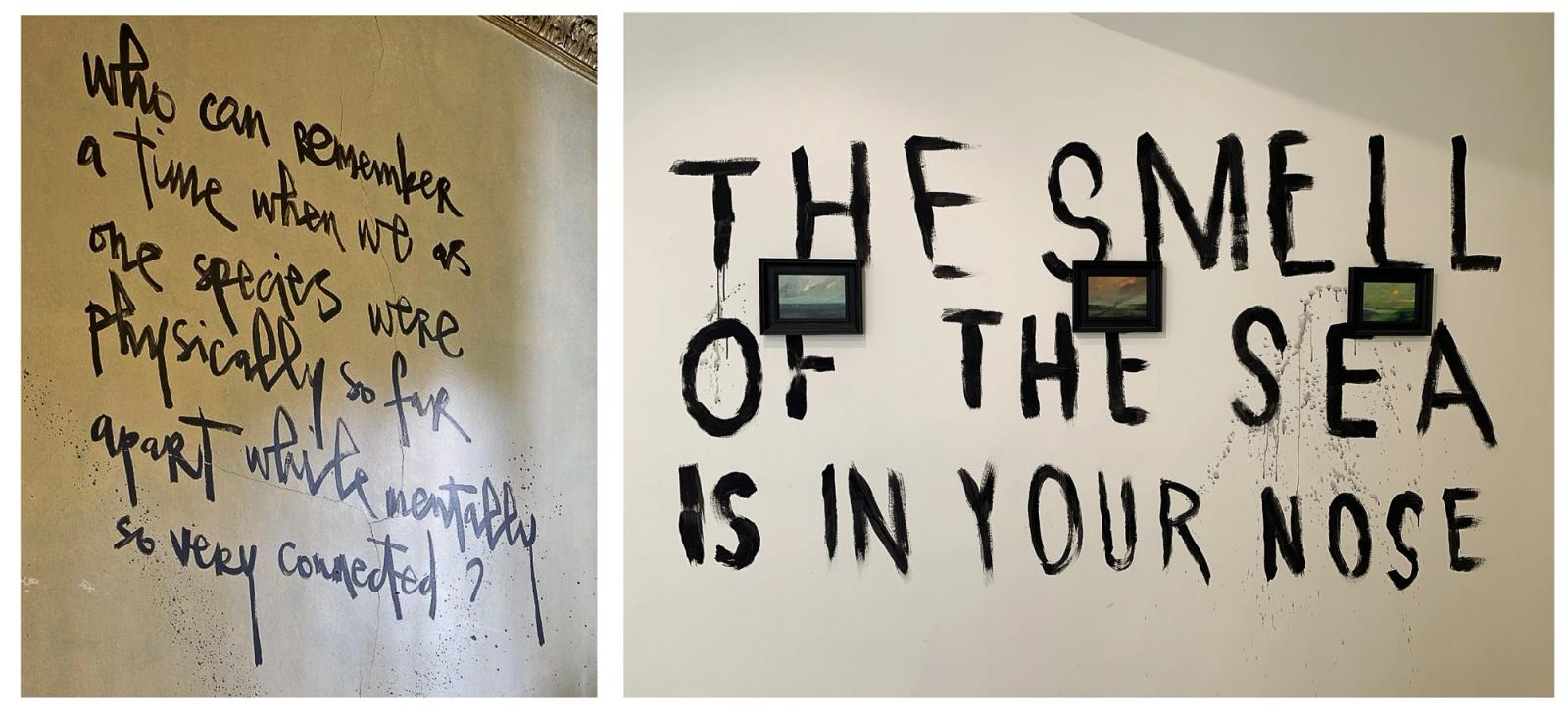

In disCONNECT LDN, the interactions, interfaces, and immersion were catalysed by multiple on- and off-site practices. Taking over a townhouse and its garden in an affluent area where artistic activities are not so common, the artists composed a specific, temporary, and spatial experience for the audience. The free of charge exhibition opened when the first lockdown was eased and provided both a somewhat unusual break from everyday circumstances as well as an opportunity for reflection. While each artist or artist duo employed their chosen methods, materials, and aesthetics, and focused on their own room or space, the exhibition as a whole highlighted a multitude of effects and emotions that had been evoked by the pandemic, from societal concerns, panic, and escapism to fear of crowds, hope, anxiety, and resilience. Hence, the first layer of the interactive immersiveness derived from a collaborative transformation of a private space into an artistic experiment as ‘a house of pandemic’ open to the public.

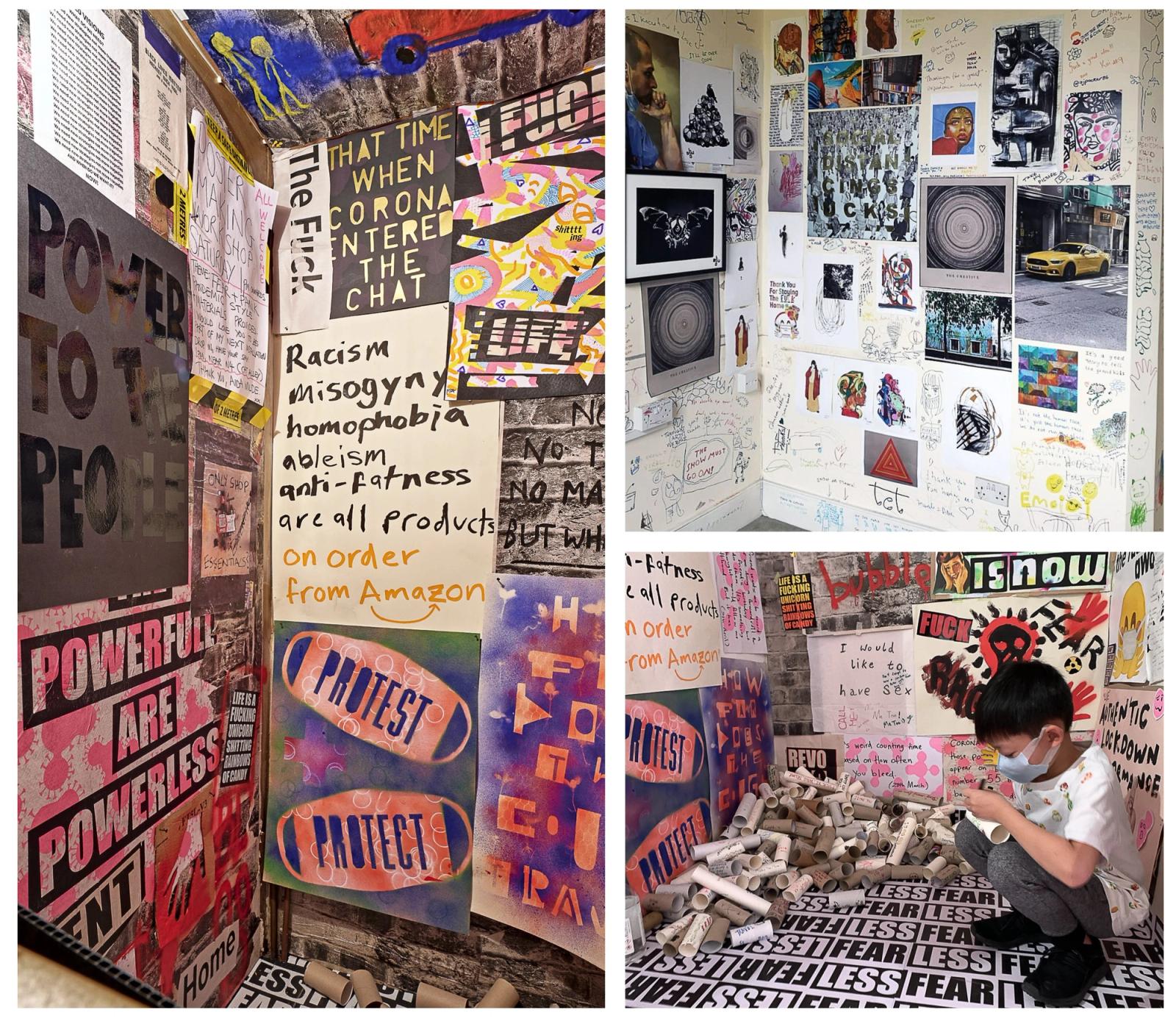

In addition to the spatial experience of visiting a private Victorian townhouse, the layout and design of the artworks throughout the rooms introduced further tactics of immersion. In particular, in rooms where viewers were fully encompassed by the artworks (e.g. Alex Fakso, David Bray, Mr. Cenz) or summoned to physically position themselves in the installations (e.g. Zoer's car, Herakut's chess player, Aida Wilde's Pandemic Panik Room), the affect could be overwhelming. As for the artworks that primarily invited the visitors to pay close attention to the details and their surroundings in the house and the garden (Adam Neate, Isaac Cordal, Vhils, Icy and Sot), these too engendered further nuances in terms of their multilayered site-responsiveness, which enhanced the overall emotional experience of the visit (Figures 3, 4).

Whereas direct (physical) interaction between artists and audiences was not possible in London at that time, other ways were developed for members of the audience to engage with the exhibition. Aida Wilde's installation included posters which were collaboratively pre-made in a workshop in June while creative contributions to the Wall of Fame were stimulated by distributing online free colouring books designed by Mr. Cenz, Wilde, and David Bray. In addition, both analogical and virtual communications through various channels (handwritten messages on empty toilet paper rolls, social media platforms, and artists' video interviews) were encouraged and eagerly made use of. Some of the artists took it upon themselves to reply to social media messages to interact directly with members of the audience.

In disCONNECT HK, the practices for generating interactions, interfaces, and immersion were adapted to local circumstances, the artworks, and to the two sites which differed from each other and from the site in London. With the support of event partner Lee Gardens Association and venue partner Hysan Place, the area and venues less common for artistic activities were chosen for the exhibition in Hong Kong: a renovated 1950s tenement building in Pak Sha Road and a pop-up space, Urban Sky, at Hysan Place in Causeway Bay. Organising most of the exhibition in the residential building and distributing it over three floors that used to be three private flats with different floor plans, to some extent echoed the London townhouse structure. In such a historical site, rich in architectural detail, and in an area otherwise known for its offices and manufacturing companies, the exhibition provided an unusual and accessible break from everyday patterns. Both exhibitions also aimed to connect with heritage and to open up an originally private and domestic space to the public.

The atmosphere and surroundings were inevitably very different from those in South West London, but in disCONNECT HK too, the tangible site and its infrastructure (with a main staircase and another one in the back) created a space that was unusual in its environment. It was a temporary realm in which one could enter not only to explore the artistic responses to the pandemic but also to interact and mirror one's own experiences. Like in London, it therefore offered the possibility for affective immersion during the visit, which was further enhanced by the fact that one could walk from one floor to another at one's own pace, not only as part of a guided tour as in London. Even though the general curatorial layout of the exhibition was spatially more fluid in Pak Sha Road, and artworks by different artists partially shared the same space, some similar work-specific immersion tactics were employed and some new ones were added in the newly planned site. Besides being surrounded by Herakut's installation (with local children's contributions) or being closed into Aida Wilde's pandemic-wallpaper-bathroom, visitors were keen to watch Kacey Wong's video installation called The Quarantine, and pause to sit in Jaffa Lam's installation entitled, Rocking in Mini Zen Garden to be surrounded by stones, plants, the soundscape of a beach, and the warmth of UV lights (Figures 6, 7).

While the small pop-up space of Urban Sky resembled more of an ordinary gallery space with its curatorial approach, the large screen displaying a video from disCONNECT LDN in a loop hinted at the international interaction and communication that lay at the core of the whole project. The door handles of the London townhouse that Go Hung recreated as soap sculptures also highlighted such interconnectedness between the two cities. Further engagement with Hong Kong audiences was generated through a live-painting by Wong Ting Fung on the opening day, three workshops by Go Hung, a group discussion, a series of artist interviews available online, and 22 guided tours, some organised in collaboration with local nonprofit organisations and all without charge.

Yet another realm of immersiveness in these on-site exhibitions was provided by the virtual online displays that offered both the chance for a re-visit and even more importantly, made them accessible for those who could not travel. Such flexibility provided opportunities to share the experience, for instance, with an elderly relative living in another city, as was recalled by James Reeve, the house manager in London. Obviously, the virtual exhibition cannot offer the same affective experience as the on-site visit, but it may provide further opportunities for sense- and memory-making. In particular, the artwork-specific soundscapes that were not available on-site affirm an additional layer of immersion, available only online. For instance, Zoer created the sound space with his musician friends especially for this project. He was keen to investigate the interrelation between volume, sculptural characteristics, and the density of the object for the virtual experience. Together with the sound effects that simulate the sounds created by moving around the house (thumping, squeaking, dripping, chirping, and rustling, among others), the high-resolution 3D documentation that allows close examination of the materials and details, contribute to the immersive effect online. As Grau has elaborated in detail, illusion and immersion are often interdependent aspects, especially in a virtual space:

[…] the illusion works on two levels: first, there is the classic function of illusion which is the playful and conscious submission to appearance that is the aesthetic enjoyment of the illusion. Second, and by intensifying the suggestive image effects and through appearance, this can temporarily overwhelm perception of the difference between image space and reality. This suggestive power may, for a certain time, suspend the relationship between subject and the object, and the ‘as if’ may have effects on awareness. The power of hitherto unknown or perfected medium of illusion to deceive the senses leads the observer to act or feel according to the scene of logic of images and, to a certain degree, may even succeed in captivating awareness. This is the starting point for historic illusion spaces and their immersive successors in art and media history. They use multimedia to increase and maximize suggestion in order to erode the inner distance of the observer and ensure maximum effects for their message. (Grau, 2002: 17)

While there is a difference between the image space of the virtual exhibition and the reality of the viewer's surroundings – also due to the technical devices facilitating the virtual visit, as Bolter & Grusin (1999: 21–22) remind us – several aspects may blur these distinctions. For instance, the video installations are fully embedded into the virtual displays of disCONNECT HK and hence provide a simulative experience of viewing them on-site. A time-lapse of the walk between Pak Sha Road and Hysan Place, although somewhat accelerated, also gives the illusion of ‘being there’ in person. Yet other dimensions for imaginative engagement not available on-site are effected by views and modes of illusion.

The ability to examine the entire London townhouse and its interior, or the three-floor exhibition space in Pak Sha Road as a ‘dollhouse’, evokes both an illusionistic and an immersive approach. This is further encouraged by imaginative ways to interact with the virtual interface, such as rotating long-distance perspectives and transporting oneself virtually from any one spot to another (through floors and walls). Such digital affordances, and especially, as Isaac Cordal elaborated, this possibility ‘to view from above, from the perspective of the God, which is becoming the new normal, is changing something in us and how we think about the world and the universe – we are our own satellites.’ For Jaffa Lam, the transparency and 3D rendering enhances the virtual exhibition visit, ‘you feel like you are taking an adventure’. If viewed in a quiet and dim environment, through a large high-resolution screen and with headphones and/or a virtual reality headset, the online exhibition visit can be quite an immersive experience even though some haptic and olfactory sensations are missing or remain quite indistinguishable.

(Dis)engagements

[…] virtual connections are still worthwhile, they remind us that you do have a place in the world, you are not just flowing in the space alone, but you have a position. (David Bray, in an interview with the author, November 19, 2020)

For all except one of the artists, this was the very first time they had been involved in such a hybrid, multi-site cross-cultural exhibition project, with permanent virtual displays available online. Whereas these unusual working conditions and exhibition modes generated new modalities for connecting and collaborating, they also revealed aspects of detachment and dissociation. For the four artists working on-site at the London townhouse, the personal, emotionally invested experience of being and creating in situ enhanced their notions of engagement and belonging in the disCONNECT project in ways not fully possible for those working remotely, even though many were committed and thrilled to be participating.

While some of the artists had collaborated with HKwalls or Nicole Schoeni before, and most of them (working either on- or off-site) were quite familiar with some of the other artists' oeuvre and had some associations before the exhibition, most of them found the lack of physical interaction with other artists regrettable. Even the artists working on-site took turns in the house and focused on their part in total isolation from the others. Missing the chance to meet and work with the others – as is usual in group exhibitions, at least for openings – resembled the disruptions caused by the pandemic at all societal levels and left some feeling relatively disengaged from the exhibition. Yet, the very same disconnectivity made most of the artists and organisers feel closely connected emotionally. The conceptual framework that the artists shared in their works, and the way in which the exhibition was realised through technological innovation and cooperation, attest to the power of connectivity for a common cause. The notion of ‘we connected through disconnection’ in and beyond the artworks was echoed time and again in the interviews with artists and organisers both from London and Hong Kong. Although the artists mainly worked in isolation and through their own subjective perspectives and artistic sensibilities, the artworks demonstrate the collective and multi-layered in-depth consciousness about the shared issue.

Nonetheless, regardless of plans for collaborative engagement between the artists in the London and Hong Kong editions, notions of disengagement and detachment could not be completely avoided. The original idea was to deliberately focus on non-Asian artists first, then transfer their works to another cultural context and invite local, Hong Kong-based artists to respond with their own art and insights. While the project as a whole was successful and both editions received abundant, mainly very positive press coverage, some of the artists contributing to the exhibition in London felt ‘completely disconnected’ from the Hong Kong edition, especially in cases where setting up their artwork did not require much of their own input. Secondly, the artworks that were purposely designed for the London townhouse were displayed in such a different setting in Hong Kong, that the original ‘wholeness’ of the installations was disrupted. Obviously, some layers of signification were also altered. As Icy and Sot asserted, because the artwork was based on the original townhouse's table, ‘it can't have exactly the same meaning elsewhere’. Thirdly, whether or not the artists had any previous engagements with Hong Kong had a direct impact on the levels of (dis)connectedness with the artworks and sites of the HK edition. Obviously, personal memories facilitated sense-making in the new context.

The disCONNECT project revealed novel perspectives and raised new questions with regard to authenticity too. The clear majority of the original artworks were designed and made for the London house, engaging directly with its history, materials, and architectural features. While graffiti and street art are usually created by the artists themselves, it is not unheard of to have assistants work with or for you, for instance, in large-scale stencil projects that are quite impossible to realise on one's own. Also, putting up stickers on others' behalf, even in locations not visited by the artist in person, is a common practice. So, is the authenticity of an artwork reduced in any relevant measure if it is designed and created by the artist but pasted or set up by someone else on the site or spot it was designed for, in close collaboration with, and with guidance from, the artist(s)? For instance, while Wilde felt emotionally and physically exhausted after five days of intense work with an assistant in London, she was ‘over the moon with how the work translated in its entirety in Hong Kong – I would actually say, it worked better there than in London for me personally. It is just a shame and a little heartbreaking that I could not physically be there to install and to experience it first-hand but it all looked so awesome and fun.’

It could also be proposed that setting up something which is a finished piece in itself loses next to nothing in authenticity – even if significant details in lighting and the overall experiment could not be fully controlled by the artist(s). In terms of rewriting the texts on the walls – as was the case in Herakut's installations both in London and in Hong Kong, and David Bray's work in the Hong Kong edition – such finishing touches could also be seen as a form of co-creation. Without a doubt, collaborative approaches require trust and commitment, but as Hera and Bray affirmed, for them, it was intriguing to see something that appeared exactly as though it was put there by their own hand, yet was in fact executed by someone else.

Obviously, many layers of original site-responsiveness and engagement were lost when the artworks planned for the London townhouse were transferred and reset in Hong Kong. This was the case even despite careful efforts to reduce such losses to a minimum, such as maintaining the general layout of an installation or building partial walls covered with wallpaper that simulated the originals. Given that some of the artworks (e.g. a detailed painting on the wall) could not be transported, partial disconnection was unavoidable. But does such a cross-cultural transfer from one exhibition site to another diminish the authenticity of an artwork if its form allows it to be replaced without any physical harm to the work itself? This is an especially relevant question for this exhibition project, as all the artists involved knew in advance that the exhibition in London was only temporary while the intangible virtual displays would remain accessible to the public.

Such circumstances pose new questions regarding the artist–artwork relationship beyond the tangible on-site exhibition and its transfer. True, seeing one's work online and with sounds can foster wonder, disassociation, disbelief, and otherness, especially when the work has been set up by others. But it was equally true that many artists were delighted and appreciative of the quality of the virtual exhibitions and of how the artwork-specific soundscapes stirred new sentiments within themselves. The practices aimed at enhancing interactivity and immersion could, nevertheless, be developed even further if technological advancements permit. Added value, as assistant curator Angel Wai-sze Hui elucidated, could be created through a virtual ‘gallery assistant’ (a live person or a bot application) available to provide additional information to virtual exhibition visitors, or someone else to share one's impressions and experiences of the artworks with. A step further in terms of interactivity could be the development of applications that would allow shared online exhibition visits (similar to playing online games) where a group of friends could agree to meet and explore an exhibition together (e.g. through avatars), as suggested by James Reeve. Virtual exhibitions of cyber art for virtual audiences do already exist in virtual spaces, such as Second Life, but they are reserved for registered users only and in terms of image quality, are not yet able to provide high resolutions displays.

Conclusions

According to the artists and organisers of disCONNECT, despite varying practical challenges, the exhibition project exceeded their expectations. Even if taking an empty building as ‘a blank canvas’ is not unheard of, the exhibition was perceived as conceptually powerful, daring, and refreshing by the artists. Their ability to create something unprecedented together and through collaborative efforts to reach out for new audiences, sparked hopes for reconnections. As Mr. Cenz emphasised, ‘people need that hope now more than ever’, and therefore, in several ways, ‘street art is more important than before.’

As some of the artists emphasised, the virtual exhibitions provided a permanent sphere for remembering and reconnecting with their own artworks and the real exhibition, unlike in temporary, tangible group shows. Given that the virtual displays offer a full documentation of the artworks and the exhibition sites, they also attest to the novel power of the intangible for memory- and sense-making: basically, anyone with an internet connection can (re)visit and closely examine any given artwork and its engagement with the site. This opens up new prospects for artists, curators, and art researchers alike and enables them to study and reflect not only the individual artworks but the overall exhibition project. Detailed discussion on the in-depth sociopolitical reflections of each artwork is beyond the scope of this paper. The surreal circumstances of isolation, the disconnection from normal behaviour, the growing need for escapism and the long-term societal implications of the pandemic, are some key issues examined by the artists which are worthy of further research.

Besides the new media arts, scholarly discussions in museum studies have examined how virtuality, digitalisation and AR are causing changes in value creation processes in relation to experiencing art and museum visits in general. I share the call for a more nuanced understanding of how institutions ‘relate to their audiences as users of cultural content’ (Bertacchini & Morando, 2013: 60; see also Geismar, 2018), while more attention should also be given to artists' positions as the creators of cultural contents. As discussed in this paper, new digital interfaces are not unproblematic – not least because they rely on technical resources not necessarily available to everyone – but they offer unprecedented possibilities for developing multileveled interactive immersiveness in and beyond on-site and online realms. This kind of interrelated physical and virtual immersiveness improves the potentialities of both the ephemerality of tangible art exhibitions and the permanency of intangible online exhibitions.

Minna Valjakka is Senior Lecturer of Art History at the University of Helsinki. Through an interdisciplinary and comparative long-term approach bridging together Art Studies and Urban Studies, she examines urban creativity in East and Southeast Asian cities. In her current research project, Shades of Green (funded by the Academy of Finland, 2020–2024), Valjakka focuses on artistic and creative practices at the nexus of environmental issues, translocal mediations, and transformations in arts and cultural policies in relation to urban public space. Valjakka lives and works by turns in Finland and East and Southeast Asia.

- 1

The virtual exhibitions have been made permanently available online at https://schoeniprojects.com/vr, and at https://hkwalls.org/disconnect/.

- 2

Available online at https://website-schoeniprojects.artlogic.net/usr/library/documents/press-release/schoeni-projects-disconnect-hk-press-release-en.pdf.

- 3

Abundant coverage is provided by major media outlets and art platforms. See e.g., Ricci (2020), Reuters (2020), and Urban Art Mapping: Covid-19 Street Art database.

- 4

See, for instance, IOM (2020) and UNODC (2020).

- 5

For more information, see the HKwalls and Schoeni Project websites.

- 6

Nicole Schoeni, Maria Wong, and Jason Dembski in an interview with the author on July 16, 2020.

- 7

Information derives from phone and video call interviews and email messages with organisers and artists during the extended period from the beginning of July to December 2020.

- 8

To resemble the atmosphere of the original setting in the townhouse, a section of temporary walls with identical wallpaper was installed in the Hong Kong exhibition space for mounting the doors

- 9

For a more detailed discussion about the hierarchies and valorisations of the different statuses among graffiti writers and more ‘regular’ artists, see Valjakka (2018a).

- 10

On Wodiczko's own insights about his interventions, see Wodiczko (1999, especially 42–73).

- 11

For more information, see Graffiti Research Lab's blog.

- 12

An introduction with examples is available online, on Gif-iti.

- 13

For instance, laser tagging was experimented with in Hong Kong in 2007 and was planned to be used in Beijing in 2008. In 2014, INSA's collaboration with Madsteez for POW! WOW! Taiwan gained media attention. In 2019, INSA participated in HKwalls. Information derives from fieldwork notes by the author.

- 14

See, among others, Codrea-Rado (2017) and Palumbo (2018).

- 15

Originally published in an online draft of the book in 2008. Available at http://softwarestudies.com/softbook/manovich_softbook_11_20_2008.pdf.

- 16

With ‘translocal site-responsiveness’, I call for a more nuanced understanding on how the multilayered signification processes emerge in organic and spontaneous fashion, in and beyond the specific physical site (Valjakka 2018b).

- 17

The virtual tour was created by Flick360 with Matterport. The soundscapes and Isaac Cordal's ‘sculpture hunt’ were created by Elastic Teams.

- 18

Reflections on audience behaviour were discussed in detail with James Reeve, the house manager in an interview with the author, November 13, 2020.

- 19

Available on the HKwalls website: https://hkwalls.org/disconnect/disconnect-london-a-locked-down-artist-takeover-en-2/#colouring-books.

- 20

James Reeve, in an interview with the author, November 13, 2020.

- 21

Zoer, in an interview with the author, November 22, 2020.

- 22

Isaac Cordal, in an interview with the author November 27, 2020.

- 23

Jaffa Lam, in an interview with the author, December 23, 2020

- 24

For instance, the dreamlike impact of UV lights on the colours and aesthetics of Mr Cenz's paintings proved irreproducible in the virtual realm.

- 25

Icy and Sot, in an interview with the author, November 30, 2020.

- 26

Aida Wilde, in an email to the author, December 7,2020.

- 27

Angel Wai-sze Hui, in an interview with the author, 7 January 2021.

- 28

Mr. Cenz, in an interview with the author, 7 December 2020.

Bertacchini, M. & Morando, F. (2013) ‘The Future of Museums in the Digital Age: New Models for Access to and Use of Digital Collections.’ International Journal of Arts Management, 15(2): 60–72.

Bonadio, E. (2019) ‘Does Preserving Street Art Destroy its “Authenticity”?’ Nuart Journal, 1(2): 36–40.

Bolter, J. D. & Grusin, R. (1999) Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Codrea-Rado, A. (2017) ‘Virtual Vandalism: Jeff Koons's “Balloon Dog”’ Is Graffiti-Bombed.’ The New York Times, October 10, 2017. [Online]. Accessed 15 December 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/10/arts/design/augmented-reality-jeff-koons.html.

Erll, A. & Rigney, A. (2009) Mediation, Remediation, and the Dynamics of Cultural Memory. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Geismar, H. (2018) Museum Object Lessons for the Digital Age. London: UCL Press.

Di Giacomo, G. (2020) ‘Contextualizing Graffiti and Street Art in Suitable Museum Settings. Street Art Today's Upcoming Museum in Amsterdam.’ SAUC – Street Art & Urban Creativity Scientific Journal, 5(2): 56–65.

Gif-iti (n.d.) [Online] Accessed 5 October 2020. http://www.gif-iti.com/.

Glaser, K. (2018) ‘Notes on the Archive: About Street Art, QR Codes, and Digital Archiving Practices,’ in: Blanché, U. & Hoppe, I. (eds.) Urban Art: Creating the Urban with Art, Lisbon: Urban Creativity, 56–62.

Graffiti Research Lab. (2009) [Online] Accessed 10 November 2020. http://www.graffitiresearchlab.com/blog/.

Grau, O. (2002) Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gwilt, I. (2014) ‘Augmented Reality Graffiti and Street Art,’ in: Geroimenko, V. (ed) Augmented Reality Art: From an Emerging Technology to a Novel Creative Medium. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 189–198.

Hansen, S. (2018) ‘Street Art as Process and Performance: The Subversive Streetness of Video-Documentation’, in: Blanché, U. & Hoppe, I. (eds.) Urban Art: Creating the Urban with Art, Lisbon: zUrban Creativity, 81–91.

IOM. (2020) ‘We Together: Street Art for Safe Migration and Solidarity during the COVID-19 Pandemic. June 9, 2020. [Online] Accessed 15 November 2020. https://www.iom.int/news/we-together-street-art-safe-migration-and-solidarity-during-covid-19-pandemic.

Manovich, L. (2013) Software Takes Command. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Palumbo, J. (2018) ‘Street Artist Escif Is Using Augmented Reality to Challenge the Boundaries of Graffiti. Artsy, August 30, 2018. [Online] Accessed November 3, 2020. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-street-artist-escif-augmented-reality-challenge-boundaries-graffiti.

Parker, E. & Saker, M. (2020) ‘Art Museums and the Incorporation of Virtual Reality: Examining the Impact of VR on Spatial and Social Norms.’ Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 26(5–6): 1159–1173.

Popper, F. (2007) From Technological to Virtual Art. London: MIT Press.

Reuters. (2020) ‘Art of the Pandemic: COVID-inspired Street Graffiti.’ 16 October 2020. [Online] Accessed 15 November 2020. https://www.reuters.com/news/picture/art-of-the-pandemic-covid-inspired-stree-idUSRTX82S3I.

Ricci. B. (2020) ‘Coronavirus Street Art: How The Pandemic Is Changing Our Cities.’ Artland [Online] Accessed 15 November 2020. https://magazine.artland.com/coronavirus-street-art-how-the-pandemic-is-changing-our-cities/.

Skwarek, M. (2014) ‘Augmented Reality Activism,’ in: Geroimenko, V. (ed) Augmented Reality Art: From an Emerging Technology to a Novel Creative Medium. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 3–29.

UNODC (2020) ‘Senegalese Artists and the UN Fight Together against COVID-19.’ May 12, 2020. [Online] Accessed 15 November 2020. https://www.unodc.org/westandcentralafrica/en/2020-05-12-un-street-art-covid.html.

Urban, A. (2018) ‘Spatial and Media Connectivity in Urban Media Art’, in: Blanché, U. and Hoppe, I. (eds.) Urban Art: Creating the Urban with Art, Lisbon: Urban Creativity, 63–71.

Urban Art Mapping: Covid-19 Street Art. (2020) [Online] Accessed 15 November 2020. https://covid19streetart.omeka.net/.

Valjakka, M. (2018a) ‘Translocal Site-responsiveness of Urban Creativity in Mainland China’, in: Valjakka, M. & Wang, M. (eds.) Visual Arts, Representations and Interventions in Contemporary China. Urbanized Interface, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 285–315.

Valjakka, M. (2018b) ‘Beyond Artification: De/reconstructing Conceptual Frameworks and Hierarchies of Artistic and Creative Practices in Urban Public Space’, in: Blanché, U. & Hoppe, I. (eds.) Urban Art: Creating the Urban with Art. Lisbon: Urban Creativity, 37–48.

Wilkins, G. and Stiff, A. (2019) ‘Hem Realities: Augmenting Urbanism through Tacit and Immersive Feedback.’ Architecture and Culture, 7(3): 505–521.

Wodiczko, K. et al. (1992) Public Address: Krzysztow Wodiczko. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center.