Protest banners on buildings are not an unusual sight in Berlin. They are typically found on what might be called ‘disobedient buildings’ − occupations, squats, autonomous house projects, and other sites that rehearse alternative modes of (co)inhabiting the city − where they form part of a broader visual culture of resistance, placed alongside political graffiti, posters, flags, and other objects that convey the site-specific politics of a particular building.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has introduced fundamental shifts to the terrain and conditions of urban political activism, the practice of displaying banners on buildings has come to transcend its habitual setting. Handmade protest banners now drape over balconies and window sills of private apartments all throughout central neighbourhoods of the city. Within the broader visual assemblage of COVID signs and performances − social distancing marks, public health notices, graffiti and street art, balcony choreographies − they stage a kind of #stayathome protest, claiming the very threshold between interior and exterior, private and public as a site for extended performances of political expression and solidarity (see Andron, 2020a & 2020b).

Occupying the urban landscape rhizomatically, these banners offer a response to the historical conjuncture of pandemic and protest through both content and form. As registers of political action based on the collective and embodied occupation of public space have been largely suspended, the banners articulate demands for horizontal solidarity and mutual care, and against racist and colonial violence at the very place which most people now largely find their lives confined to: the home. In relying on the specific affordances of the protest banner as a durable and mobile artifact of resistance (Posters, 2020; Sifuentes, 2018), these dispersed yet interconnected instances of political expression ultimately gesture beyond the contemporary moment towards the possibility of a return to embodied forms of protest and solidarity.

Within the broader context of the pandemic cityscape, conceptualised by urban scholars as a site of ‘waning sensuousness’ (Lancione & Simone, 2020a) characterised by a ‘shrinking sense of our world’ (Low & Smart, 2020,: 2), these interventions foster contingent encounters between city dwellers and the environment they inhabit. By imbuing the walls of the city with a sense of political and affective urgency, they invite a kind of reattunement with the urban landscape ‘that can contribute to a renewed sense of intimacy’ – and, I would argue, political potentiality ‘with and through the extended world we inhabit’ (Lancione & Simone, 2020b).

Disobedient Buildings

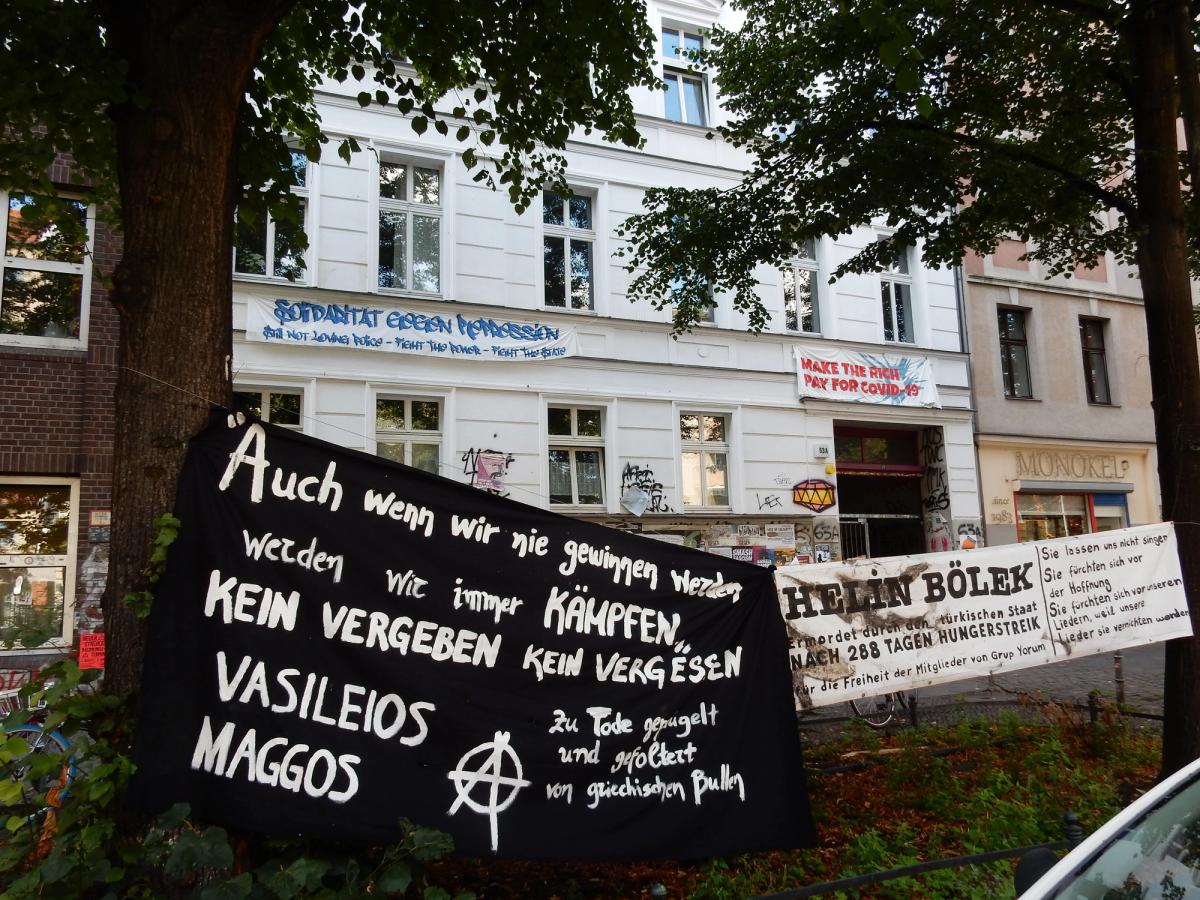

The natural habitat of protest banners within the Berlin cityscape are squats, autonomous house projects, and occupations. ‘Part direct action, part performative art’ (Posters, 2020: 101), banners are here displayed in changing constellations that dynamically respond to urgent political matters and emerging situations.

The blue building is Liebig34, a queer-feminist house project in Friedrichshain, photographed shortly before its contested eviction in October, its facade covered in anti-police slogans and calls for resistance. The white building is Reiche 63A, a self-organised house project in Kreuzberg and home of the anarchist library Kalabal!k, with banners on and in front of the building responding to the COVID-19 pandemic (‘Make the rich pay for COVID-19’) as well as the transnational threat of police and state repression. The black banner on the left reads:‘Even if we will never win, we will always FIGHT – No forgiveness, no forgetting! – VASILEIOS MAGGOS beaten and tortured to death by Greek cops.’ The white banner on the right reads: ‘HELIN BÖLEK killed by the Turkish State AFTER 288 DAYS OF HUNGER STRIKE – Freedom for the members of Grup Yorum – They don't let us sing, they fear hope, they fear our songs because our songs will annihilate them’.

Leave no one behind

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the shifting degrees of lockdown it imposed on public life, political banners have proliferated beyond their usual spatial embedding and come to adorn everyday residential spaces.

The most common iteration of the #stayathome protest banner simply bears the words ‘Leave no one behind’, a slogan and hashtag that emerged from a solidarity campaign and petition initiated in March 2020. ‘Leave no one behind’ signifies the demand for protections for those most vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic: the homeless, the elderly, and, most urgently, the thousands of refugees forced to live in the unsafe conditions of overcrowded camps at the borders of Europe. Photos taken in Neukölln, Kreuzberg, Alt-Treptow, Prenzlauer Berg, and Friedrichshain.

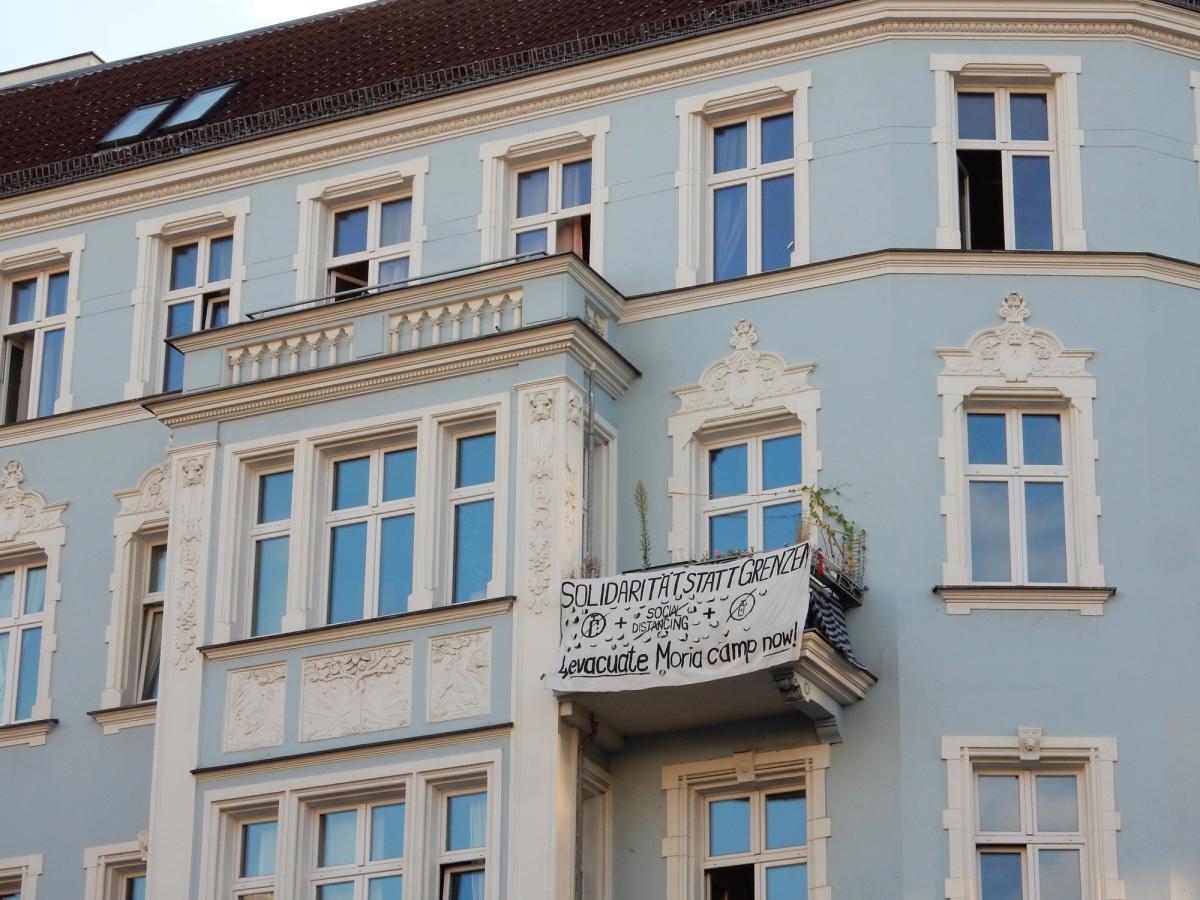

European Border Regime

Other banners more explicitly condemn the violence of the European border regime. In a case of eerie foreshadowing, many of them call for the evacuation of Moria refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos (‘Solidarity, not borders’, ‘Protect people not borders’), a place that like no other symbolises the failure of European solidarity in the context of the pandemic. Built to house 3,000 people, yet chronically overcrowded with an occupation close to 20,000, Moria burnt to the ground at the beginning of September. The camp had presumably been set on fire by inhabitants desperate to escape their situation and an impending COVID outbreak. Photos taken in Neukölln, Prenzlauer Berg, and Alt-Treptow.

Anti-racism

Several other interventions signal their solidarity with the global mobilisation against anti-black racism and violence in the aftermath of the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May 2020, galvanized by the Black Lives Matter movement. Photos taken in Neukölln, Alt-Treptow, and Prenzlauer Berg.

Hanau

Others engage more specifically with articulations of racist violence specific to Germany's own history and present, for which the city of Hanau has become the most recent site of reckoning. Here, on February 19, 2020, a far-right extremist attacked two Shisha bars, shooting nine young patrons, later killing himself as well as his mother. The incident has laid bare the systematic failures of the German police apparatus to prevent and adequately respond to racist violence.

While the six-month anniversary demonstration to commemorate the lives lost in Hanau was cancelled with just one day notice due to the heightened risk of pandemic transmission, in Berlin the memory of Hanau remains ever present in the public consciousness as DIY banners, along with countless posters and stickers, remind passersby to say and remember the names of Ferhat Unvar, Mercedes Kierpacz, Sedat Gürbüz, Gökhan Gültekin, Hamza Kurtović, Kaloyan Velkov, Vili Viorel Păun, Said Nesar Hashemi, and Fatih Saraçoğlu.

Julia Tulke is a PhD candidate in the Graduate Program in Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester, USA. Her research centers on the politics and poetics of space, with a particular focus on material landscapes of urban crisis as sites of cultural production and political intervention. She maintains a long-standing interest in political street art and graffiti as performative repertoires of protest. For her ongoing research project Aesthetics of Crisis, Tulke has documented and examined street art and graffiti in Athens, Greece since 2013.

- 1

The term ‘disobedient buildings’ borrows from Catherine Flood and Gavin Grindon's ‘disobedient objects’ (2014), a term that describes the material cultures and practices of object-making adopted by social movements.

- 2

In July 2020, 27-year-old Vasileios Maggos was found dead in his home by his mother, exactly one month after he was severely beaten by police in his hometown Volos in Greece during a protest against the burning of garbage by a local company that was allegedly polluting the atmosphere.

- 3

Helin Bölek was a Kurdish member of the leftist Turkish folk music band Grup Yorum. She died on April 3, 2020, the 288th day of a hunger strike at her home in Istanbul, which was held as a means to protest against the treatment of her band by the Turkish government.

Andron, S. (2020a) ‘Covid surfaces. Public walls in lockdown London (1).’ [Online] Accessed August 30, 2020. https://sabinaandron.com/2020/05/17/covid-surfaces/.

Andron, S. (2020b) ‘Covid surfaces. Public walls in lockdown London (2).’ [Online] Accessed August 30, 2020. https://sabinaandron.com/2020/06/04/covid-surfaces-public-walls-in-lockdown-london-2/.

Flood, C. & Grindon, G. (eds.) (2014) Disobedient Objects. London: V&A Publishing.

Lancione, M. & Simone A. (2020a) ‘Bio-Austerity and Solidarity in the Covid-19 Space of Emergency - Episode One.’ Society and Space. [Online] Accessed August 30, 2020. https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/bio-austerity-and-solidarity-in-the-covid-19-space-of-emergency.

Lancione, M. & Simone A. (2020b) ‘Bio-Austerity and Solidarity in the Covid-19 Space of Emergency - Episode Two.’ Society and Space. [Online] Accessed August 30, 2020. https://www.societyandspace.org/articles/bio-austerity-and-solidarity-in-the-covid-19-space-of-emergency-episode-2.

Low, A. & Smart, A. (2020) ‘Thoughts About Public Space During Covid-19 Pandemic.’ City & Society 32(1). [Online] Accessed August 30, 2020). https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/ciso.12260.

Posters, B. (2020) ‘Banner Drop’, in The Street Art Manual. London: Laurence King Publishing”: 101-109.

Sifuentes, A.H. & Hall, K. (2018) ‘Aram Han Sifuentes on the Protest Banner Lending Library.’ Houston Center for Contemporary Craft. [Online] Accessed August 30, 2020. https://crafthouston.org/2018/12/aram-han-sifuentes-on-the-protest-banner-lending-library/.

All photographs courtesy of ©Julia Tulke and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The images shown were selected from a larger body of 150+ photographs of protest banners captured in Berlin between July 15 and September 3, 2020. The entire data set can be accessed on the photo sharing platform Flickr via this link: https://bit.ly/30TGWtF.