Congratulations on the launch of The Street Art Manual. How long was the process of working on this book? Does the final form match your original vision?

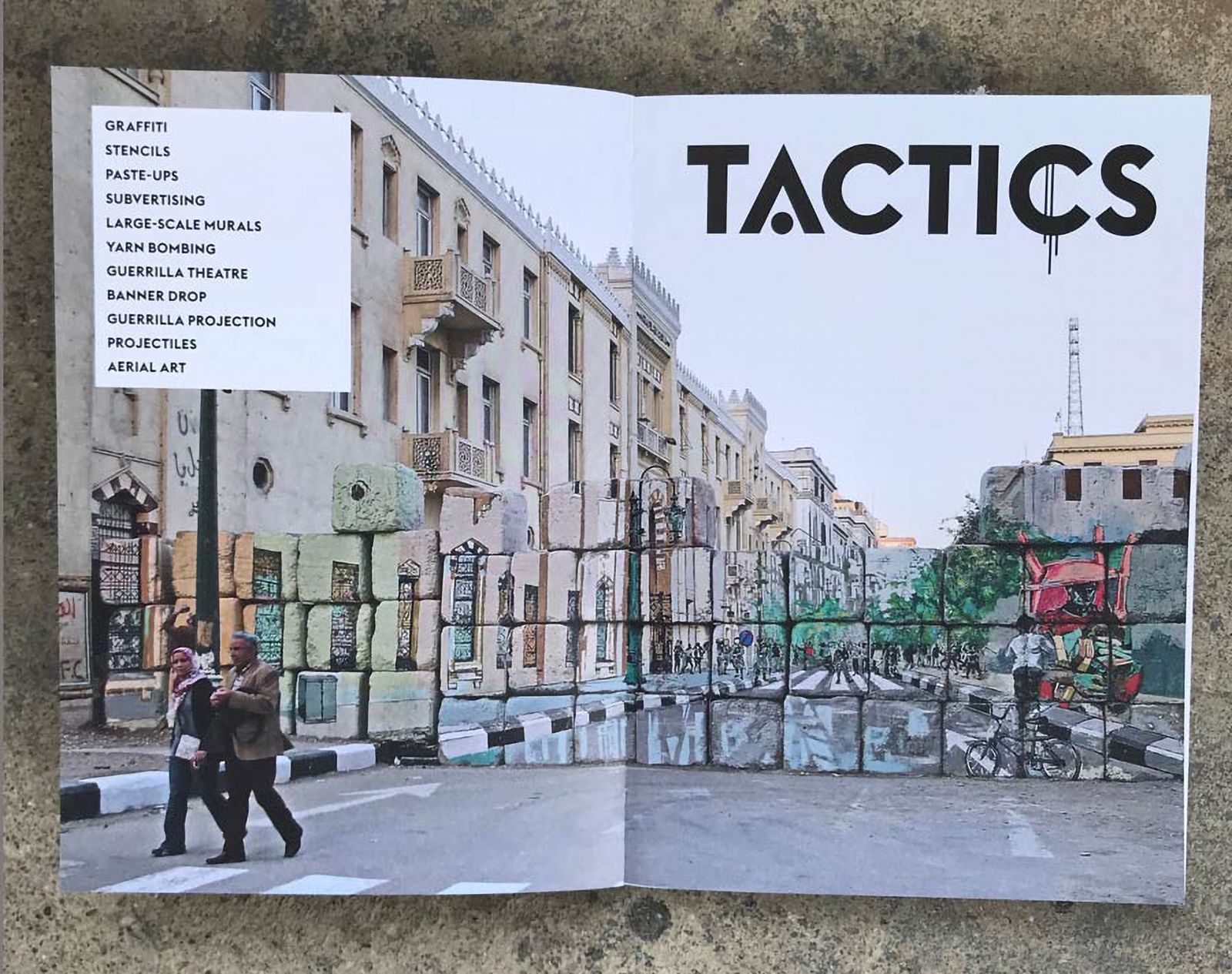

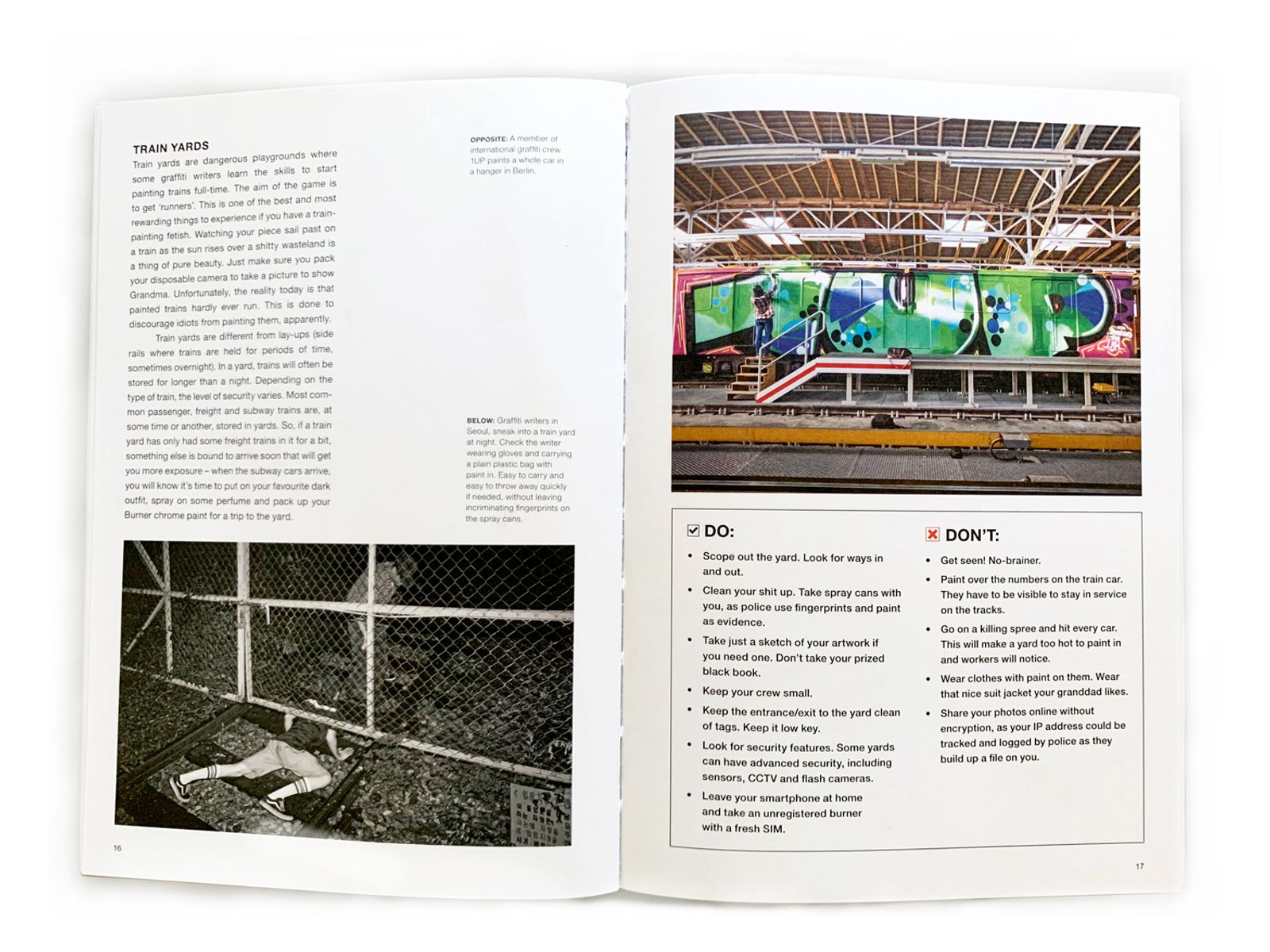

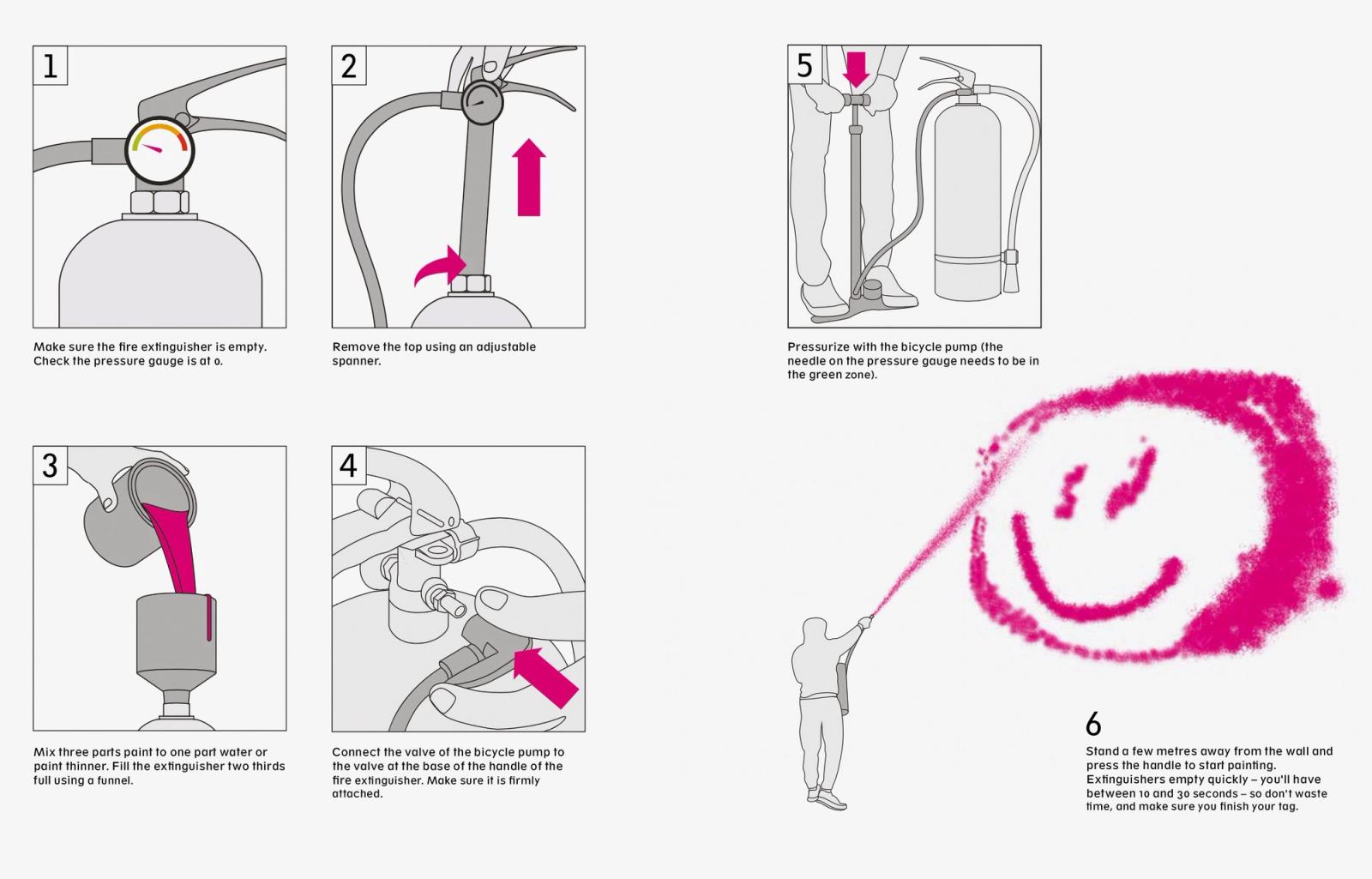

Thanks. It's been a little while in the pipeline, so it's really good to finally get it out there into people's hands where it's needed. The original idea for this book is based on the same type of framework of a book I wrote about subvertising in 2017. It was a subvertising manual built around what you need and how to do it, and it was released with Dog Section Press, an anarchist publisher based in London. This new book concerning street art and creative activism in public space was based around the same format and framework of that initial publication. There was interest from Laurence King Publishing to do something similar but that covered a much wider scope of forms of street art and that became the basis for the concept of The Street Art Manual. It includes the social political history of 11 forms of street art, and an expanded section at the beginning of the book around best practice for hacking public spaces, and then an additional series of chapters exploring trespassing, accessing, and infiltrating sites such as abandoned buildings, rooftops, train yards, and high security areas. It was almost two years from the initial conversations to the release of the book. In terms of the writing process, I wrote the initial 30,000 words in about six weeks in autumn 2018 because the publishers wanted to try and slot it into a ‘spring 2019 release window’ and they thought there was a good scope to turn it around that quickly, so I literally just ate, slept and breathed this book into being and completed the first draft of many in a relatively short time frame.

That sounds painful.

Yeah it was, but it was valuable because I went very deep into the subject matter, and I was privileged to have the space in my day-to-day life to be able to allocate six weeks to that first draft. As you know, the editing process is much longer than that and it took a further eight to nine months of edits and development before the book was ready for the design phase.

The book does feel quite coherent − sometimes a book this ambitious in scope can feel a bit incoherent and bitty, because so many topics are crammed in.

Thank you, I really appreciate that. Yes, the book does cover a lot of areas and attempts to provide theoretical and value-based frameworks that cut across art forms in public space alongside examples of artworks and actions by artists and collectives operating in five continents. Content has also come from fifteen years of my personal street art and creative activism practices. I have a lived experience and relationship with 10 out of the 11 forms of street art I cover in the book, but there were also a lot of informal advisors and supporters from across the street art scene that have aided in the development of chapters and my thanks and respects are given to them in the book. I feel that the book's strength is definitely in the sum of its parts and as you know I'm a big fan of collective processes.

Which is the one street art form that you haven't tried?

Yarnbombing. That's just the one that's been least accessible for me personally. I've had experiences that bridge a connection to the radical history around craftivism via activism and it was really exciting to draw together threads in this chapter in order to challenge some boundaries and try to connect some dots to this art form. The collectivised element to craftivism is especially powerful, you see it with the interventionist works of individual artists who have a collaborative intervention approach to a yarnbombing installation. I think that is one of its main strengths on the process side. In the book, I constantly try to make the case that process is possibly more important than aesthetic output, and I try to ground different forms of street art within that framework because it can be so individualist. This was really inspiring to learn more about when researching into yarnbombing.

Decentring the idea of an individual author or artist?

Yes. The movement, its origins and its history of art, has a heavy element of collective process and community. These ‘Do It Together’ (DIT) values and principles were really strong − you can see it in the strength of early graffiti ‘crews’ − even more so in the noughties. The street art movement and the first wave of street artists were deeply anti-consumerist and anti-capitalist when they emerged into popular culture, and the question of how we can connect our knowledge back to some of these foundational principles is really one of the main points of focus of this book. As history consistently shows us, as soon as a subculture emerges into popular culture, it grows, becomes profitable, and inevitably internalises the values of capital which can change the nature of the subculture. This book attempts to wrestle street art back from the void a little bit.

So, that's the intention of the book?

Alongside other aims, yes. My research was focused on how can I apply this critical learning and try to reconnect younger audiences today to the really powerful forces that street art can manifest − and that's through process and experiential kinds of engagement as much as it is through aesthetics, scale, and the socio-political environmental context.

The book is a crossover text. Your writing style seems very democratic – the book has lots of accessible practical and legal tips but you mix this with critical theory, history, and politics. This is quite unusual − most manuals for street art or stencils or paste-ups seem based primarily on process, not politics.

Thanks for drawing that thread through, because you've hit the nail on the head. Nothing exists in a vacuum. Everything is political. One of my personal motivations with this book was concerned with how can I get a widely distributed, mass-produced book about street art, that looks very benign and is very accessible and relational, yet within it is a deeply critical set of ideas, of politics, and of social activism. To illustrate this, I wanted the cover to look friendly and non-threatening, I didn't want it to look sharp and edgy. And I don't think it should either as the content in this book is really in line with what many forms of street art were primarily concerned with at their inception. This book is about repopularising some foundational key principles and ideas about street art and is aimed at those that are now coming up around the world – especially young people not living in the West. Thanks to the support of some high profile street artists providing images and guidance I feel that we did this quite well.

So basically you fool people into buying the book for their kids?

I would reframe this slightly – how can we create a publication that can simulate and subvert popular culture at the same time? Because if I'd gone to a large publisher like Laurence King with some of the content that's in there now in the beginning, there would possibly have been a lot more push back against this book, but throughout they were very willing to support an activist project which is quite surprising when you look at their back catalogue.

It's impressive that you pulled that off. But I can see that the publishers have put a disclaimer on the inside front cover?

Yes, but I think that is fairly standard. I thank the editors at Laurence King for being so open and seeing value in the project. They could've just said, ‘no, this is too edgy for us’ or ‘we want it to be soft and non-political’ etc. The editor for the book is Chelsea Edwards and she was incredible throughout and ensured the focusses of the book stayed strong. It turned out we had actually met several years earlier during a direct action protest in a coal mine in Wales!

There's also a strong legal section and practical guidance chapter at the back in case you get arrested in any country in the world. From a global perspective, it became a really important theme to provide good, solid practical advice for how to deal with fascist or racist police, ‘tricks of the trade’ in case you do get busted as well as tips on how to stay safe online whilst still sharing your work, especially if you are in a country that heavily oppresses free expression or political dissent. This will hopefully provide good foundational sets of knowledge that will stop people getting into unnecessary trouble, whilst giving them confidence in process and belief in their own power to create art in public space with others.

In the book, you actively interrogate your own privileged identity as a white guy doing street art.

Absolutely. And I try to provide guidance for others to do this as well. Not in a weird white saviour way, but if you are in a crew that has black or brown friends in it, just making sure that everyone's got each other's back is really important, especially when dealing with security or the police. Because if you have someone who feels safe handling the police or a problematic interaction due to their privilege, it's crucial to think about this before you go out and to make a plan. So, I wanted to try to demystify that, because most people who read the book could be predominantly white, possibly male and ‘Western’ − even though the book has been written for global audiences. It's trying to be international in its focus, but you have to draw that out and take a critical look, and to ask the reader to take a critical look at themselves as well, especially concerning how they relate to others within certain contexts where white privilege is the difference between a potentially positive interaction with police or an incredibly negative and oppressive one.

It's good to see that level of critical consideration. Moving on to your chapter on murals – some people might argue that a large-scale mural is something that's almost impossible to execute without permissions, cherry pickers, and days of authorised work. Yet in the book you very much focus on street art as an unauthorised and self-organised process. Do large scale murals really fit as one of these renegade tactics?

Well, there is an incredibly long history of muralism across continents in the world that has existed for millennia before the good old cherry picker was invented, so I would definitely question the Western-centric framing on this one. There are many methods to create a large mural in the city, one of which is illustrated in the diagrammatic ‘step by step’ section for this chapter.

Murals can be both authorised and unauthorised in nature and there are tangible benefits to both when it comes to process and self-development for those involved in the creation. Whilst I make the case for the value of unauthorised art throughout the book, it isn't the only method that has value and forms of authorised art are also supported and referenced in the book. When it gets to something as involved as a large-scale mural, it's true that it takes time on site, but there are hacks around that. You can simulate the signifiers that give an official semblance to what it is you're doing, making sure, for example, you have some visible element of health and safety, like cones or tape that make it look like it's a managed safe space. Street art doesn't have to be unauthorised or illegal, I just think that it retains more of its power socially if that is the case. I do try and make an argument in the book that conscious trespassing in particular is super important as a formative process. It is a provocation for finding new visions for social, cultural, or political possibilities for life. By transgressing those boundaries and stepping out of the norm you realise that all frameworks are conditional − it's only when you cross those boundaries that you realise just how much behaviour, how much activity, or how much cultural creation is controlled within that space. You need to cross these boundaries to try and see things from the other side and discover this whole constellation of possibilities that you might not have considered before. And then the learning of that journey is really what I think is so rich about street art, because it gives you power and agency. You can express yourself, which is fundamentally, foundationally important. Having an experience of doing something and getting away with it is a richly rewarding gateway form of street art.

It's great that you've included a section on graffiti, but this is possibly also a contentious inclusion to some people − especially as a form of ‘street art’. Many people would characterise graffiti as a separate or parallel subculture that has a history of its own. Also, you've collapsed a lot of different forms of graffiti − political graffiti, NYC style graffiti, etc. − into one narrative, and there's no actual graffiti in the modern sense pictured in this chapter. What was your thinking behind this?

This one did cause a bit of a headache when considering the rich histories of graffiti and how these could be combined into the framework for the book. There is an extensive collection of books that go deep into those different types of graffiti, writings that are much more authoritative than what I could possibly produce with a thousand words. I decided that I definitely wanted to include it as an art form in public space. I absolutely agree there are disputed relations to the history, trajectories, and cultures of graffiti. It's such a fascinatingly complex form of art that it was worth including an overview from a specific perspective – that of the social history of tagging – than to leave out such an inspiring and rich form of art in public space.

If we look at the history of graffiti, in the book I provide a basic overview of the historiography, but we're talking about a timeline that goes from 50–60,000 BC to the present. What I wanted to do was to go back to tagging, to go right back to that original form of modern graffiti in public space – so I would dispute your notion that no actual graffiti in the modern sense is pictured in this chapter. My lens was to look at the social application of that original form, before it gets to throw ups and other contemporary developments. Because it's the unifying form of graffiti in public space that's universally despised, yet recognisable, whether you are in Botswana, Lagos, New York, or Chile. And when there's a bit more of a hidden history in there − from the Pixadores in Latin America and Brazil who were developing tagging at the same time as those in New York in the '70s – there's a deeply political component of that action too. These predominantly young boys coming out of the barrio, going to hit up wealthy neighbourhoods, climbing up residential skyscrapers to tag them up and then heading off back to the barrios. It's insurgent.

This chapter extends this line of enquiry to look at how graffiti tagging has also been central to social justice movements. That's why that image from Don McCullin is in there (from the UK in the '70s) with two young black boys looking into the camera, while it says in antifascist graffiti in the background ‘No Nazis in Bradford’. Writing in public space has been key to loads of social movements and political revolutions, from Latin America to the Middle East: think of acts of resistance against Pinochet in Chile, uprisings in the Gaza Strip and the Westbank, and more recently the revolution in Egypt. If there's one thing I wanted the graffiti chapter to do, it was to make a case that tagging is valid and it's important, and it can be powerful. But there's also a few tongue-in-cheek things in there, like the instructional ‘what you need and where to get it’ − it just takes the piss out of itself − you don't really need a manual to do art on the streets, and you certainly don't need instructions on ‘how to do graffiti’, although maybe it's helpful to have some of its myths busted in relation to technique and practice. But as far as process goes, to start you just need to get hold of a can and a nozzle and start spraying.

In the book, you also look at the nexus between street art and land art. That's something that is really starting to gain traction and seems especially evocative when it's focused on environmental activism. Land art does not necessarily manifest itself in urban space yet it comes with some of the same tactics and ethos as street art. So, you placed this street/land art combination into the category of ‘aerial art’, but I wonder whether you considered including any smaller scale or less monumental and masculine examples to represent the street art meets land art nexus?

That's an interesting one. Yes, there were three forms of art in public space that couldn't make it into the book, due to space limitations. One of them was really small-scale miniatures and micro-installations. To go from micro to macro would have been a dream. I also wanted to do a chapter on inflatables − there's a long running history of radical play and inflatables in public spaces going back to the ‘60s. In the UK and mainland Europe in particular, there have been huge inflatables in different contexts, going up to the present day with the inflatable Trump Baby. I thought this was a really rich narrative that would have been really interesting to include, but when it came to it, a brutal decision had to be made due to the lack of space, and I had to leave out several chapters. Basically, I would have had to leave out the legal guidance chapter just to fit in another form of street art and to be honest, I just thought that if we can have ten or eleven forms of street art in there, then that's quite a solid amount of content.

Aerial art in particular is quite interesting because of the cartographics involved and the way in which the artists imagine art in public space in ways that shift the axis from the vertical to the horizontal − is really exciting. We've seen some quite powerful examples of that recently, especially in relation to the racial justice movement Black Lives Matter. But some of those initiatives – for example the large commissioned street painting in Washington − have been a bit shady because they involve artwashing to make it look like the state is doing something very provocative, while in fact structurally and systemically there's not that much going on to address those deeply damaging racial inequalities in the US.

In relation to the monumental side of it being a masculine practice, yes there are male artists exploring this new territory, but there are also queer and female artists creating and leading in that space too. I think that aerial art is providing a whole new conceptual plane for the creation of art in public space that is being facilitated by emerging technologies such as light-weight and low-cost drones. This is really exciting, and I hope the examples in this chapter ignite the curiosity of the reader to get involved and explore this form of art too.

When I found the early land aerial art piece by Chilean poet Raúl Zurita, that just took my breath away. That's probably my favourite piece of work in the whole book because of the way he could articulate his trauma and express it in a poem written on a three kilometre stretch of the Atacama Desert with a bulldozer: ‘ni pena ni miedo’, meaning ‘without pain or fear’.

It was such a powerful story, learning about Raúl Zurita's struggles, and the fact that he was dreaming about writing poems in the sky while being tortured during Pinochet's dictatorship in Chile was like a big middle finger up to that oppression. He goes out and etches that into the sand for future generations. It's very moving now just talking about it. This is one of the most beautiful forms of art in public space I've been privileged to learn about and it made me think that this is the chapter that should be included above, say, miniatures or micro-art.

There must have been other more well-known Western examples of aerial art that you could have included – would these have been less powerful?

Not less powerful, just less suited to the kind of book I wanted to put together. To not include any artists or collectives from Latin America or from South America in this chapter would be to exclude the rich history of land art and aerial art that's been present in South American cultures since Nazca geoglyphs first appeared in Peru in 500 BC. So, Raúl Zurita was a bridge to the rich past of Latin America as well. The telling of that story was a leap through time to connect the reader to more ancient practices in the region. There are Western examples as well, but for each chapter I tried to create space for the voices and stories that are not the usual white male Western artists. I tried to be as inclusive as possible in bringing in stories and voices from as many different spaces, places, and cultures and histories − to get away from this whole white supremacy idea of modern art rooted in Anglo-Saxon culture. It's power that allows those stories to dictate their prominence, really. When I was writing graffiti when I was 13, if I'd have known there was an equally powerful and interesting graffiti tagg–ing movement that was going on in Sao Paolo or Brazil in the '70s at the same time as New York, that would have lit my mind on fire. But there weren't those stories or the space for those stories then.

Can you remember when you became aware of that parallel history?

Grateful as we are for them, foundational resources and guides like Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfant's images and books are super important but this is still a partial history. So, yes I'm a white male trying to facilitate some of those stories out of respect.

So, your book is a corrective history?

I'm hesitant to take on this mantle for this book as that is a huge responsibility, but I would like to think that this book celebrates more cultures and voices than mainstream street art culture has popularised. I wanted to carve some space to get more of those histories out in an accessible way to honour the rich histories and cultures that make art in public space so universal to the human condition.

And to think critically about what it is we're doing?

Yes, you don't get taught critical learning in most educational contexts today. But I am so inspired by how switched on and articulate the young Gen Y / Gen Z is right now. I go to speak in the UK, Europe or East Africa for example, and there are young people in the room from a variety of different backgrounds, but I can take five minutes and speak to any of the young people in the street, and they'll be just as articulate about what's going on environmentally, politically, socially. That for me is such a source of inspiration. I wanted to write this book to try and open source a wider array of tools, methods, ideas and foundational knowledge to ignite that curiosity and then that hopefully leads to the kind of interrogative critique that is going to be necessary if we are to escape these multiple converging crises we are facing.

Critical thinking is a weapon?

Exactly, it's a means of bolstering people's inherent power. Especially today when we have to contend with hyperreal, post-truth political and media environments. ‘Si la prensa calla entonses, que hablen las murallas’: ‘If the press is silent, then let the walls speak’.

Working under the pseudonym Bill Posters, Barnaby Francis is an artist-researcher, author and activist who is interested in art as research and critical practice. He is also co-founder of Brandalism and the Subvertisers International (SI). Poster's works often interrogate persuasion architectures and power relations that exist in public space and online. He works collaboratively across the arts, sciences, and advocacy fields on conceptual, intervention, synthetic, net art, and installation-based projects. Recently he has pioneered forms of synthetic art that include deep fake and deep-video portrait works.

Posters is a published author on the subjects of subvertising, protest art and computational propaganda. His latest book, The Street Art Manual: A Step-by-Step Guide to Hacking the City, is published by Laurence King.

International Language Editions of The Street Art Manual

English: https://smarturl.it/streetartmanual.

Spanish: https://www.promopress.es/en/manual-de-arte-urbano-1180060-000-0001.html.

German: https://www.thalia.de/shop/home/artikeldetails/ID150126809.html.