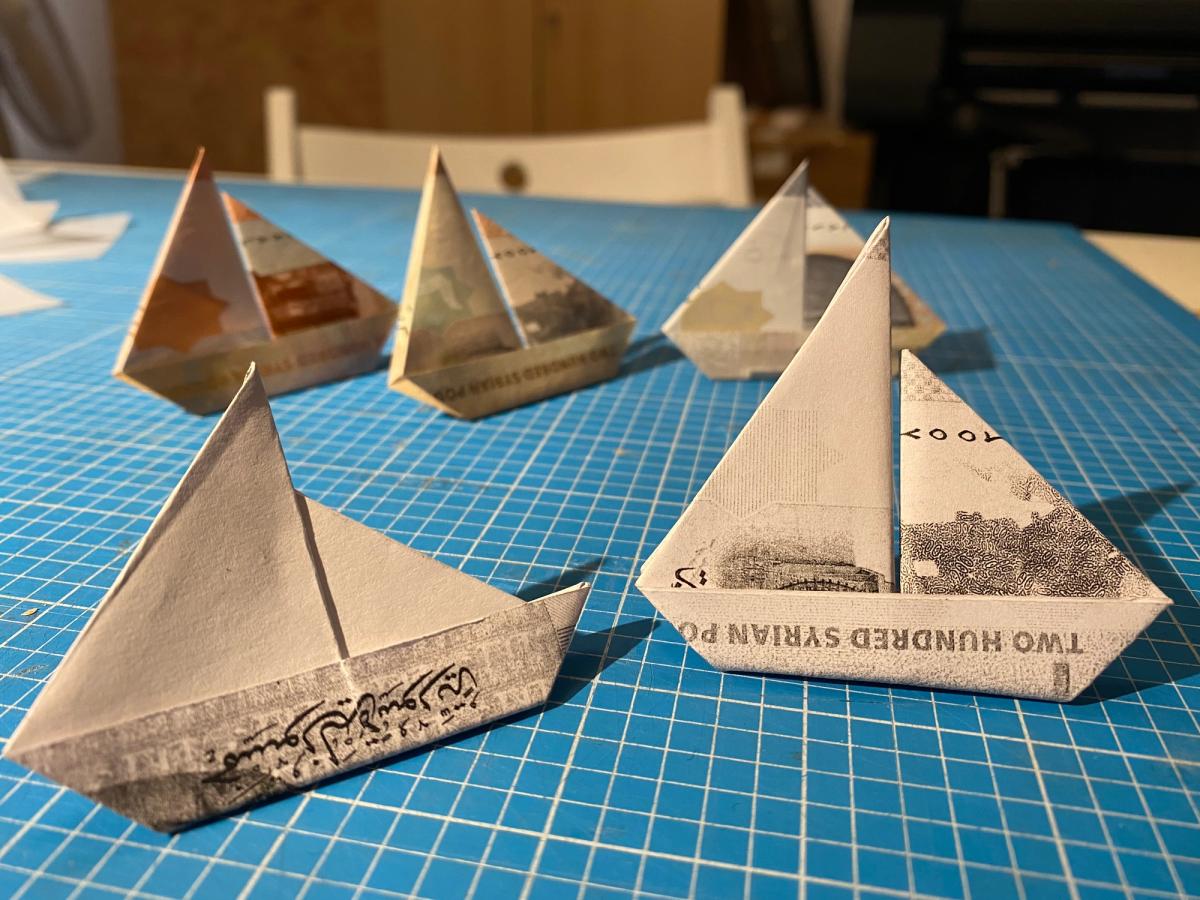

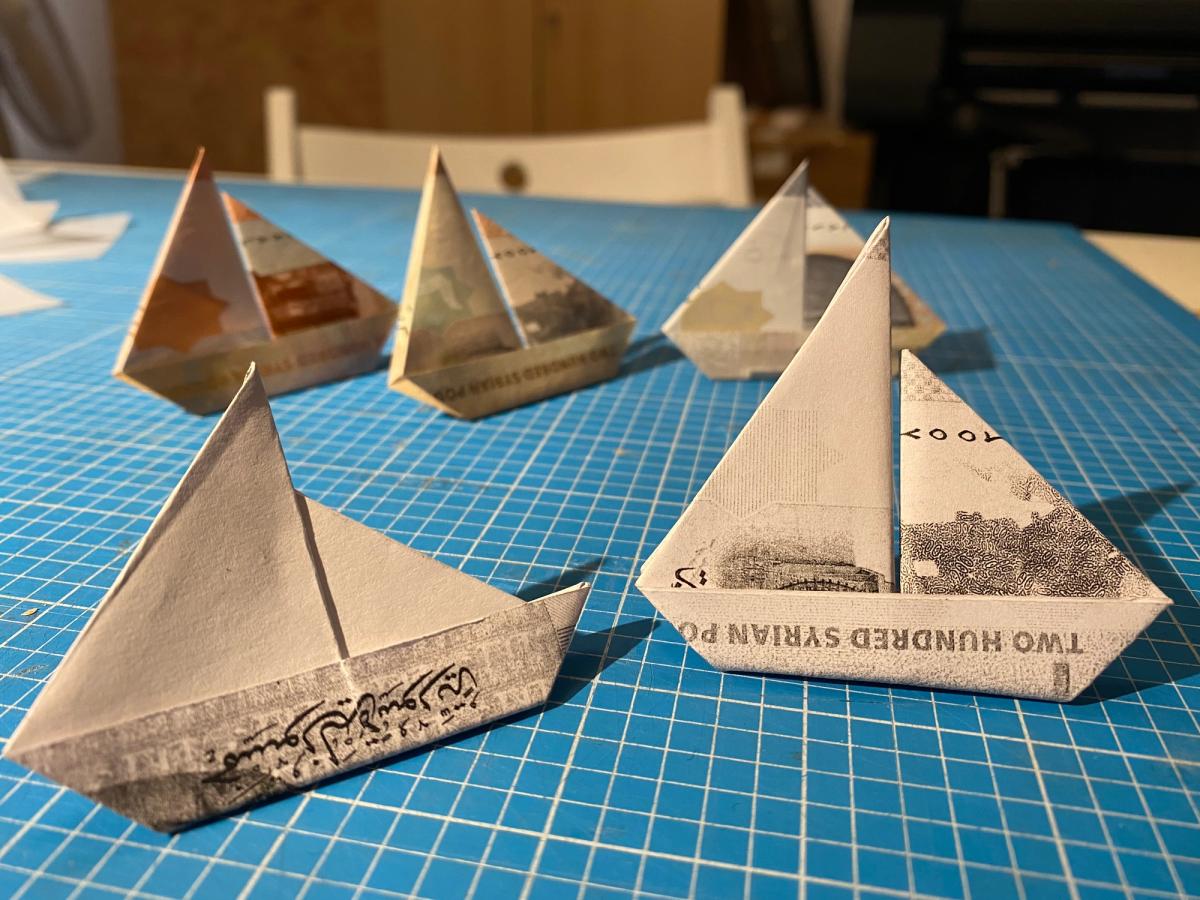

Dan Vo: Aida Wilde is a screen printer, street artist and activist who knows what it's like to experience displacement. In a piece she created to support refugee advocacy charity Choose Love, Aida uses boats as her inspiration. Rafts filled to capacity, making the perilous journey through the Mediterranean Sea, small and fragile, full of desperation and hope for a better future. Boats like these have become a symbol of the refugee crisis all over the world. Using repurposed Syrian banknotes, Wilde created ‘Dreamboat II’, a tiny origami boat waving a flag with the logo of the Choose Love campaign. Even the ink for the flag was made from pulverised Syrian currency. This piece is small and delicate, but it calls on us to remember the resilience of refugees rebuilding their lives in the aftermath of war, persecution, and natural disaster. Dreamboat II will be on display at the Fitzwilliam Museum as part of the ‘Defaced! Money, Conflict, Protest’ exhibition from the 11th of October 2022 through to the 8th of January 2023.

‘The exhibition examines the interplay of money, power and dissent over the last 200 years. A key strand of the show explores the role of the individual in protesting for rights and representation – from the radicals of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, like Thomas Spence and the Suffragettes, to current artists and activists, such as Aida Wilde and Hilary Powell, who use money to promote social and economic equality or satirise those in power. The exhibition reveals the multiple roles money played during conflict, whether it be in occupation or resistance, as tokens of memory and remembrance, created during siege or emergency, made for or by prisoners of war, or made in support of sectarian or political ideologies. Contemporary artworks by Peter Kennard, Banksy and JSG Boggs are contextualised against earlier works and reveal continuities in the targets of protest across time.’ (fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk: np)

Curator Richard Kelleher explains why the Fitzwilliam commissioned Dreamboat II: This is a key object in the exhibition. It's going to be part of a section which looks at the story of refugees and displaced people. It's going to be displayed among some other objects which touch on the causes of displacement, the movement and transit of people trying to get to new countries, their experiences in camps along the way and their reception in host countries. A Dreamboat is a powerful object for bringing this part of the story to the exhibition.

Dan Vo: Aida, what will people see when they come to have a look at this piece of work?

Aida Wilde: I hope that the message will be quite immediate as soon as you see it, even though it's this tiny little thing – it's only the size of your palm.

Dan Vo: This whole work is very much raising awareness around the refugee situation. It's an origami work, so the note has been folded up to make up this boat.

Aida Wilde: The origami idea was so simple for this note. It just made sense to make a boat, but then it turned out that I'm really rubbish at origami. I can't think in 3D, so I don't usually make 3D work. So, I was sitting in front of YouTube tutorial trying to make a boat for days and it was pretty rubbish. But I live in Hackney Wick, where we have such wealth of artists, including Michael True, who is a paper artist. So, I approached him and we experimented with a couple of shapes for the Fitzwilliam.

Dan Vo: I do like the idea that there have been so many hands that have handled this piece, in the very same way that a note is handled by many people. There’ve been so many lives that have already been touched by it and continue to be touched by it. Now that's been given a new sense of meaning as well. For you there is a very personal element to this work, I believe you're also a refugee yourself, and so there's that personal resonance in the work.

Aida Wilde: Yeah, completely. I've been practicing art professionally for 20 years or so and this was the first time that I ever addressed my heritage. In fact, when I did the first notes for Choose Love in 2019 (at Cash is King, Saatchi Gallery, London) a lot of the people that knew me well didn’t know I was a refugee. In appearance, because I'm Iranian, my skin is quite light, so everyone always assumes that I'm English. This journey I started in 2019 has actually had a huge impact in my exploration of my identity, and why I may have suppressed it, or not overtly ever talked about it or used it within my work.

My father was arrested and brutally assassinated by the Khomeini regime when I was only two, leaving my mother with me and my two sisters. So, my mum made the brave and wise decision to flee Iran. We fled to the UK. It was such a culture shock. Going from that kind of scenario to somewhere where children are running around freely, and going to school, and playing with each other. And I think I just regressed. I stopped talking Farsi immediately. It was almost like I disowned that side and heritage of myself. These are the things that I've only come to the realisation from doing this work. I'd never examined why I stopped speaking Farsi or writing or mixing with other Iranians. It was almost like I just turned my back on everything. This has been rather painful, for me because I've also realised that I feel like I don't belong any anywhere. I'm always ticking this white/other box when I fill out forms but there's never an option that really fits. So, I've started to question that as well. You know why am I ‘other’? What am I? I don’t know, it's so complicated. I'm still working through these issues.

Dan Vo: I think I was quite similar as well. I have to tick an ‘other’ box as well. But that's the nature of humanity. There are so many variations. Who and how we can be, and then to kind of say, well these are the only options you’ve got or ‘other’. Then you kind of end up in a category that doesn’t work. How can ‘other’ ever describe us? But do you want to carry on and engage with more work like this? Do you want to continue to explore this? Or do you think it's too painful to keep doing?

Aida Wilde: I'm not going to go actively making work that's just about refugees, because I like making work about a lot of things in my studio and street-based work. When I started campaigning for Hackney Wick (where artists' studios are being threatened by development) I never realised why I was pushing so hard to fight gentrification. It was only in 2019 when it came to working with Help Refugees that I've realised it's all about the home. It's all about coming under attack. That fear of displacement is constant, because we used to move a lot when we first came to England. Every other year we would either be moving or changing schools. So, I think I still have this inherent fear of being displaced, of being thrown out and of not belonging somewhere. That was another realisation I came to in 2019 that seems to explain all the work I've been doing around gentrification and displacement.

Dan Vo: I suppose the boat is a visual example of that sense of displacement. My parents were refugees too. Of course, refugees are also people, so the boat is carrying souls. It's carrying people who are seeking a new home. And I can definitely see it in this work, that metaphor, that sense of displacement. Also, I think what's really interesting is the way that you’ve taken the image of the regime that they're often fleeing from, and you've subverted it. You've turned it into a means of getting to the new place. But I know there's also lots of things that you do to the notes as well, that aren't just folding, to completely obliterate that regime or change that or subvert – there's pulping involved as well?

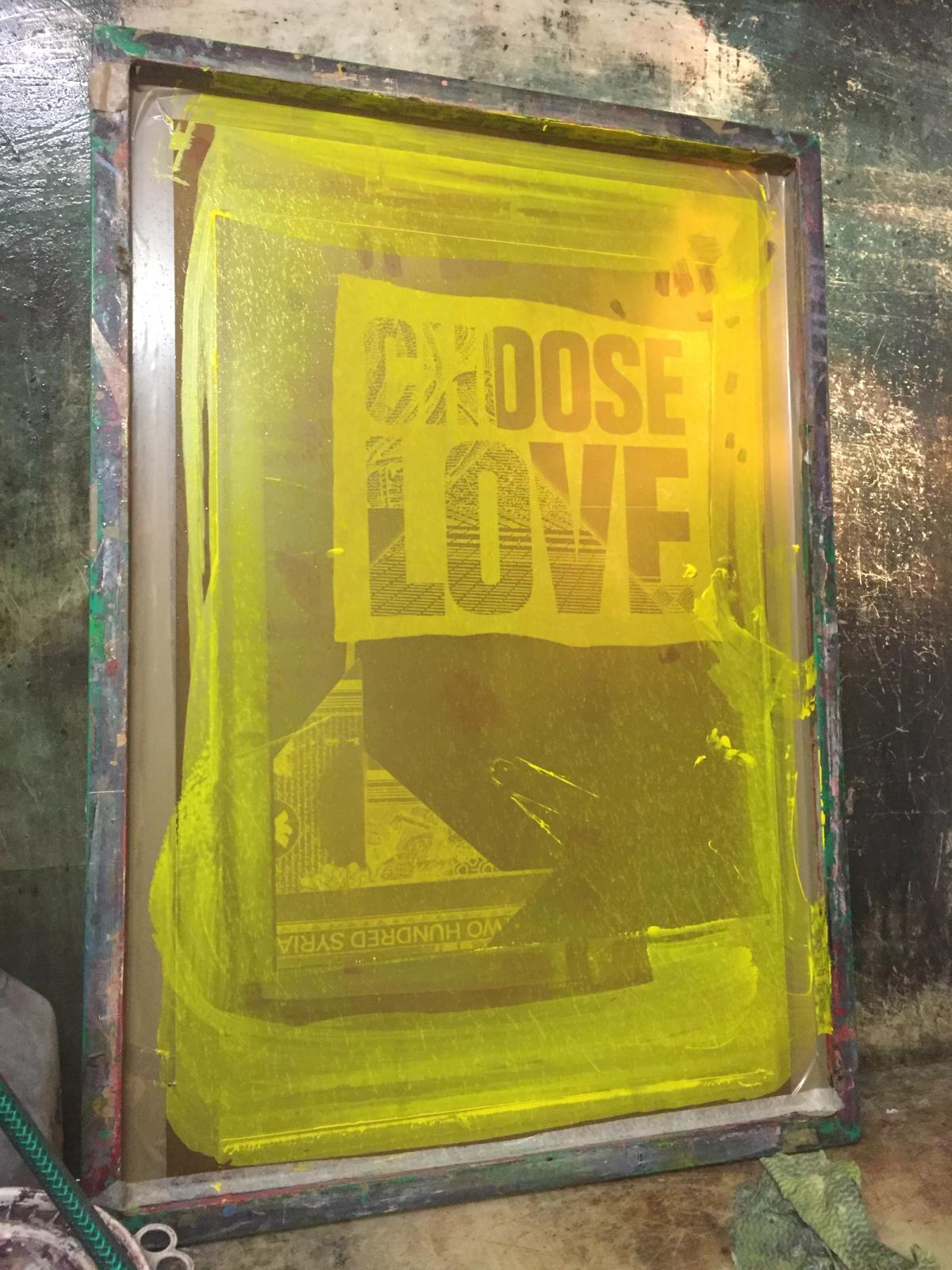

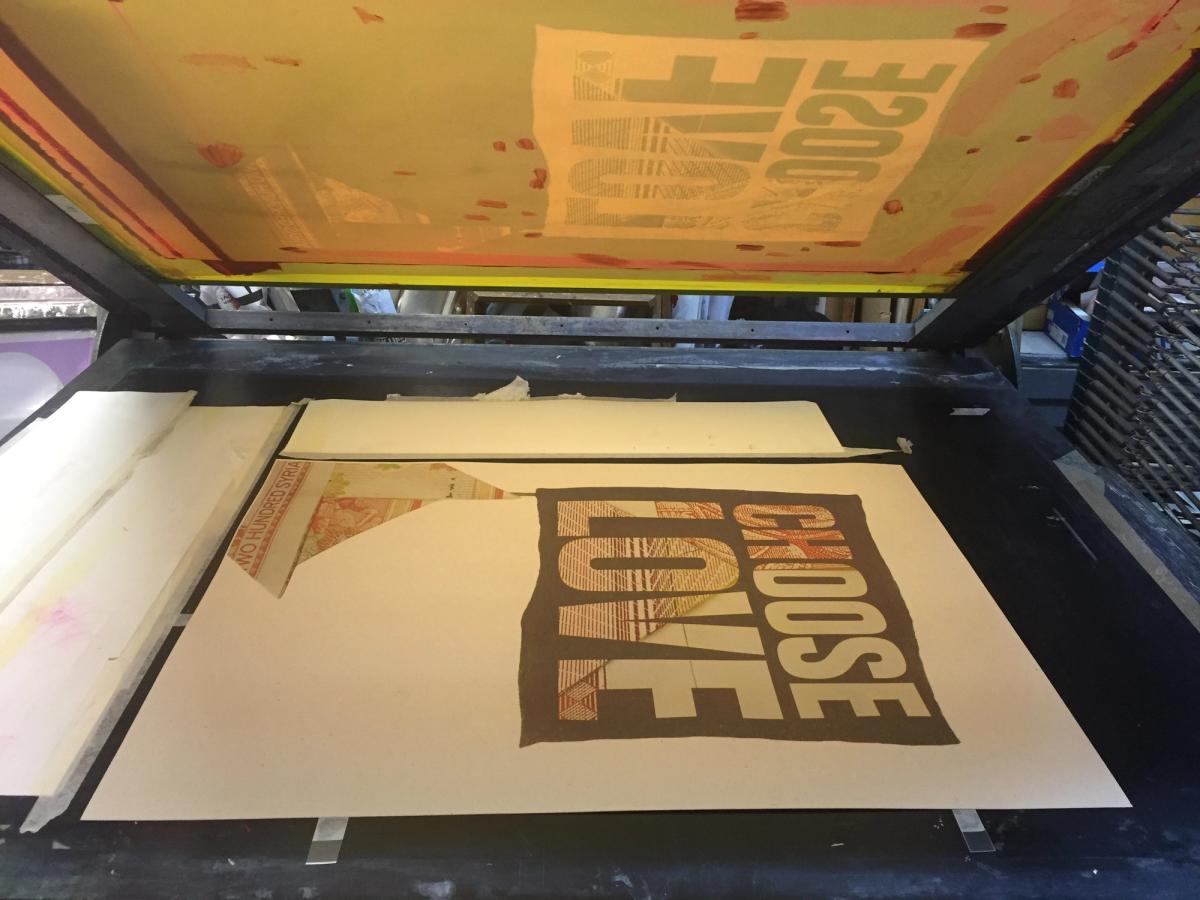

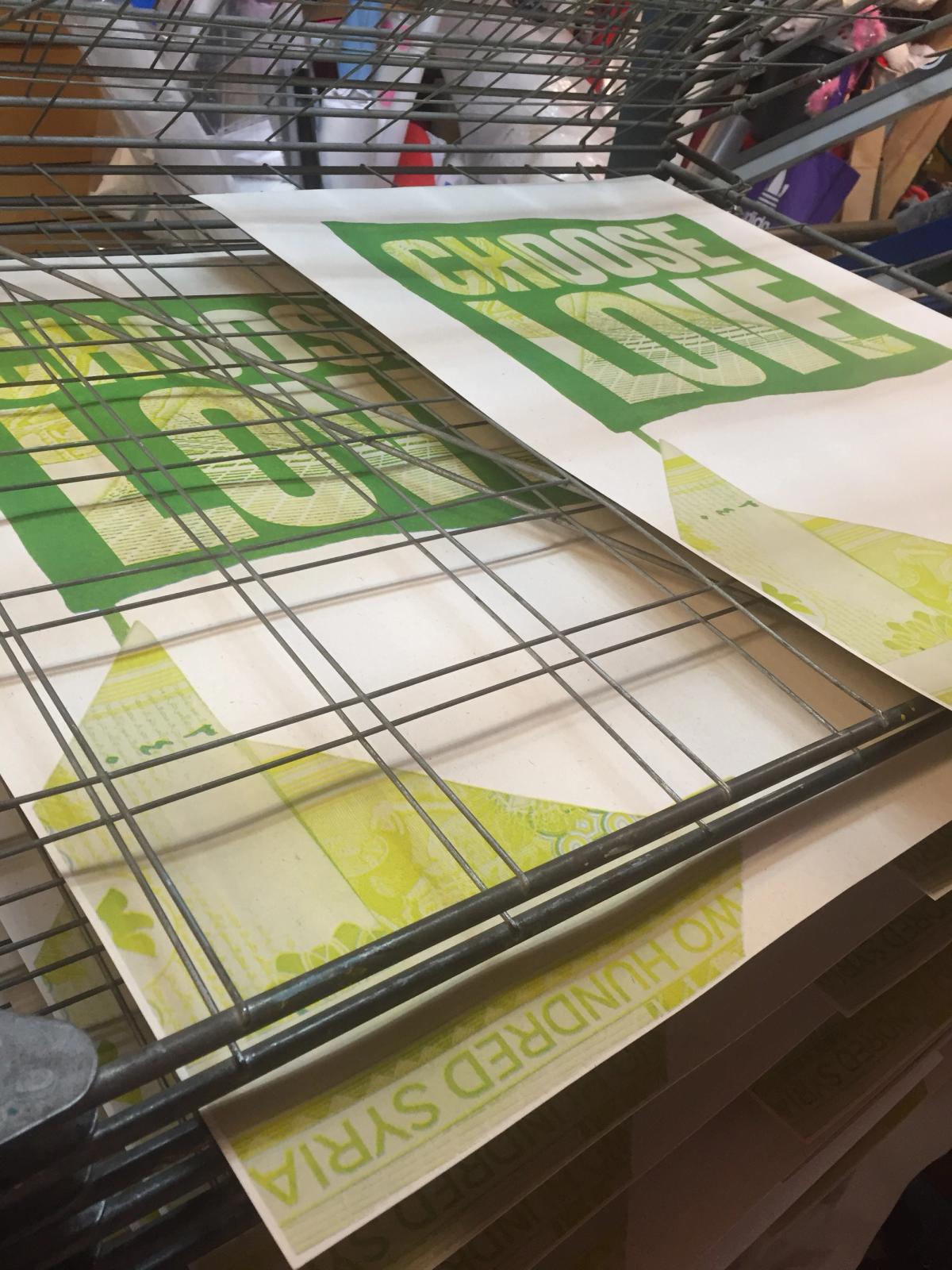

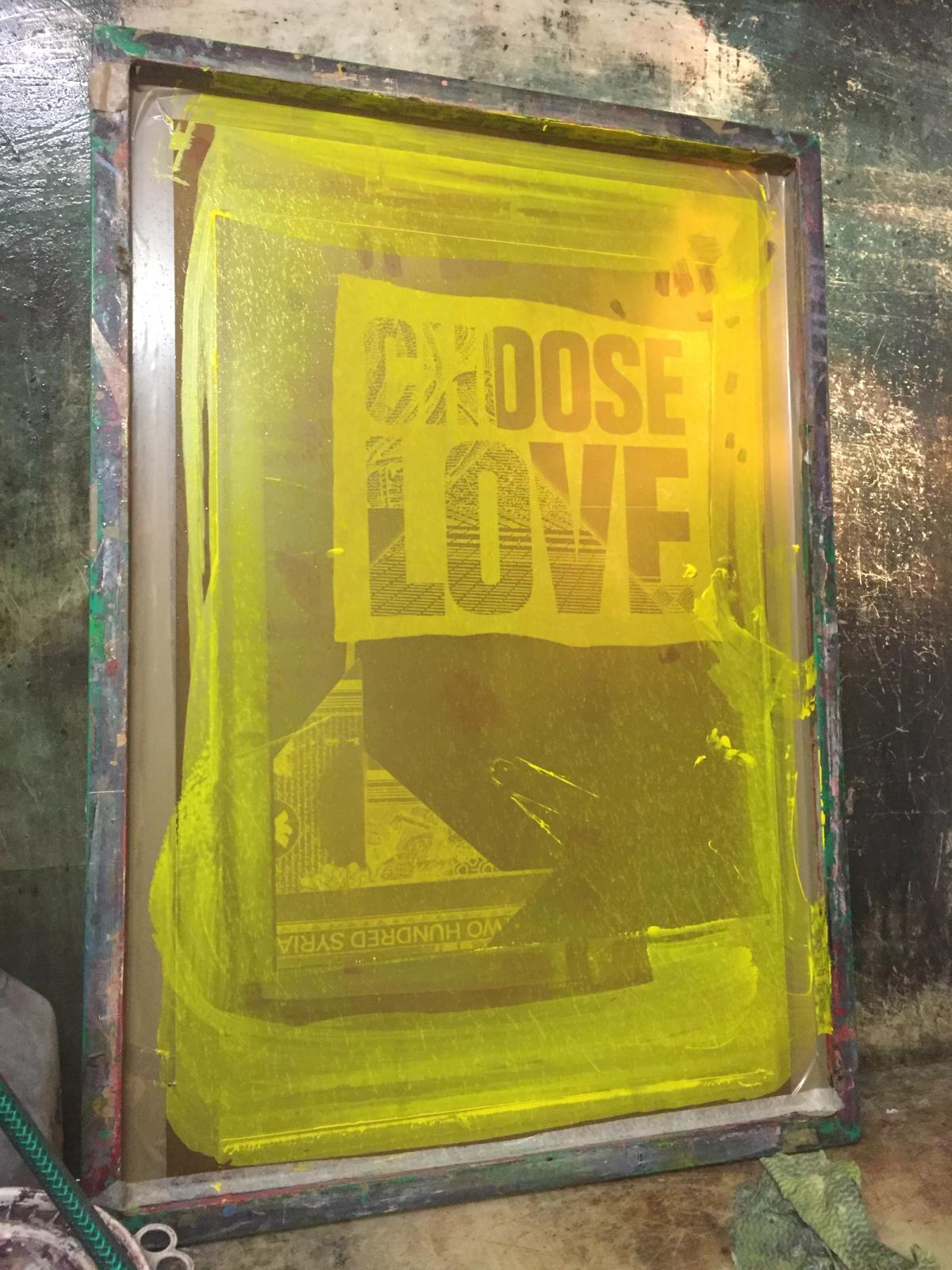

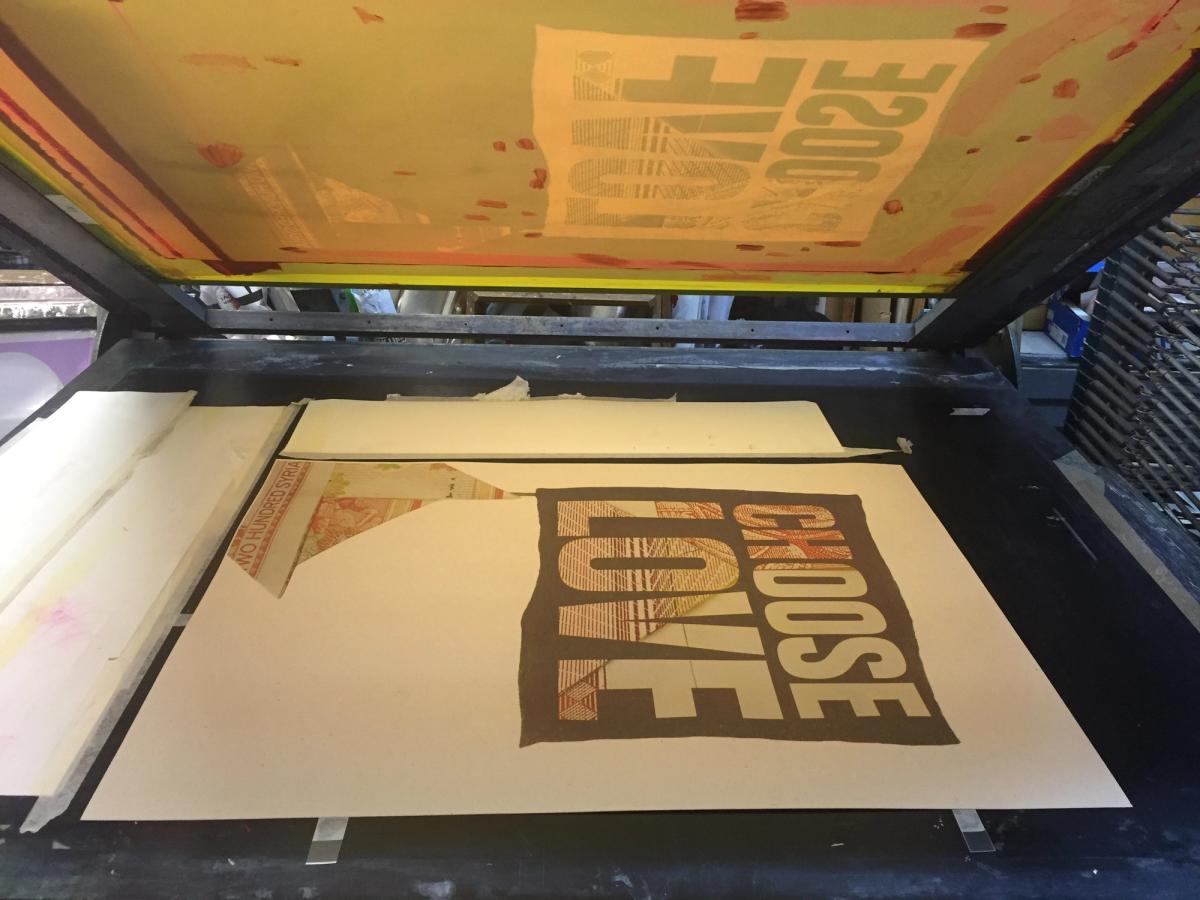

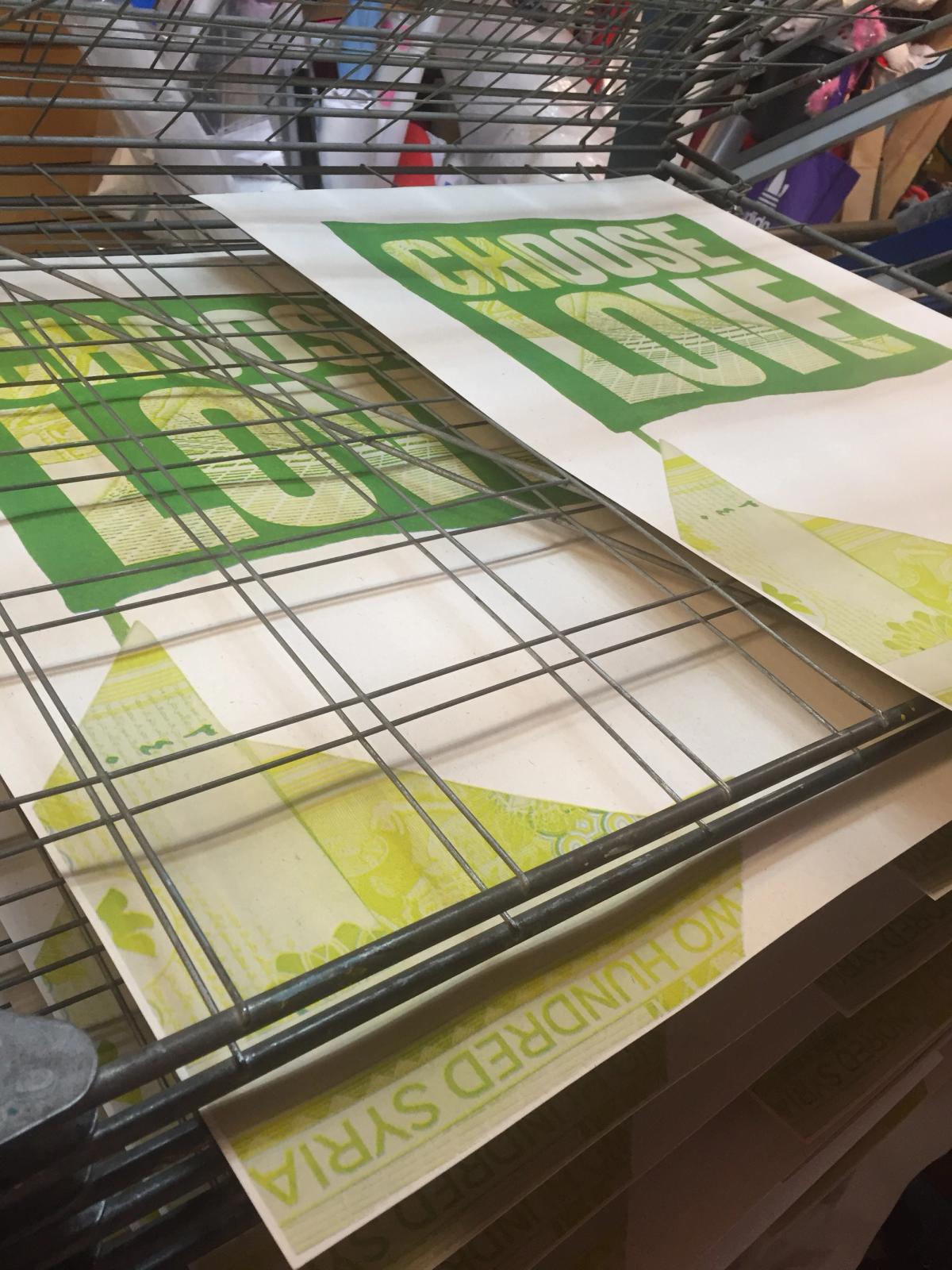

Aida Wilde: Yes, there's pulp involved – well, there's disintegration – but I discovered that you actually can't really pulp a note! It's a longprocess. I've printed with all sorts of weird things – I've burned my work and turned it into dust and printed with the ashes. I've printed with brick. I've printed with anything weird you could think of. So, this note involved three months of exploration. I literally pulped, soaked, mashed, and scraped away, and I got something like half a kilo of this pulp that I mixed into different sort of colours and ink medium, that I printed the Choose Love logo with, onto the origami boat. I think in respect when you look at look at the simplicity of the final outcome you don’t realise that as much work has gone into just printing that tiny little Choose Love flag as the process of the origami.

Dan Vo: What has really struck me with what you’ve just said is this idea of how these traces are within the print. So, you can't see them, but the traces are there, and once you know that the traces are there, I think of it a bit like human memory. There are these traces that will remain with us forever, these really tragic things that have happened. Sometimes these little traces travel between people as well. Like that metaphor of the note being passed between hands. I understand that when you first approached some of these notes, some of those traces and those memories reappeared for you and that you didn’t really want to necessarily even look at some of the notes.

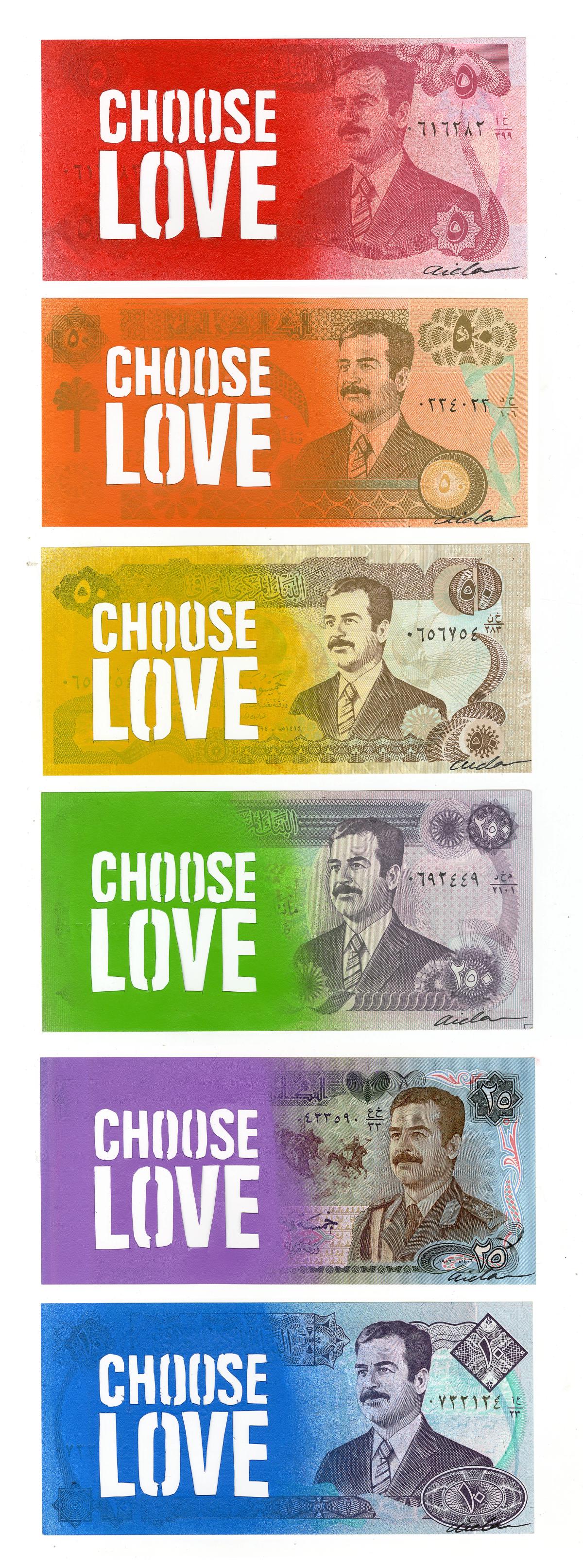

Aida Wilde: Yeah, there were these Iraqi notes with Saddam Hussein's face on. I remember the curators came to my studio and said, ‘oh, and we have these for you to work with’. And I was just repelled. I was like ‘oh thank you so, you know we've got enough to get on with, without this’, and I left Saddam to the side. I didn’t want to work with them, and it was only as I was working through ideas for the other notes that I had this revelation. I was examining Saddam's tyranny and reign and thinking about LGBTQ+ rights, and people getting stoned for their sexuality, and that's where the rainbow idea came from for these Saddam Hussein notes. Reimagining these notes as a rainbow flag links us to the horrific human rights abuses LGBTQ+ people in Iraq have suffered, and to the experiences of LGBTQ+ refugees who then have to ‘prove’ their sexuality once they reach safety. I printed a Choose Love on each of these notes in different colours, but then as a stencil, I cut Choose Love out, and I used the note to spray a rainbow-coloured artwork from it, which used all of the notes.

These notes once had value. And then they became obsolete as countries go through civil unrest or war. So, now these notes are kind of worthless. And I think that sometimes, when we are dealing with refugees, and looking at their plight, and the mass exodus of people fleeing, they become a whole, and you stop seeing the individual. You stop seeing each life as worth something. And maybe we just forget that actually, this person could be a father, mother, uncle, brother, sister. And then people talk about lives lost, like you're just taking a sip of water or something. But every life matters.

Dan Vo: What I'm getting from this, is this idea that we create value. It's something that otherwise in someone else's hands is just pulp. We create value, and so we should be choosing how to put value on things. So, you can choose love or you can choose monetary value. You can choose economics, or you can choose to actually see humanity, as you’re suggesting. What does it mean to you, to be having this work placed in the Fitzwilliam Museum?

Aida Wilde: I just wanted to raise more awareness. The Choose Love campaign has grown so rapidly in the last few years, which is just phenomenal. My initial feeling was, I just wanna raise some money. So, I didn’t even really think too much about the museum, although obviously it's an honour to be asked. It's so important, especially for someone like me. If you think about where I was born and where I've come from and now I have a piece in the Fitzwilliam – how did something like that happen? So of course, it's such a privilege and an honour.

Dan Vo: Well, it's going to be a major exhibition. It's called ‘Defaced! Money, Conflict, Protest’ and it's opening in October 2022. But if you think that people like you aren't supposed to be in the museum, and people like me aren't supposed to be in a museum but suddenly, your work is in the museum and suddenly I can take a group of refugees, or the children of refugees to the museum to show them your work. How does that make you feel?

Aida Wilde: It reminds me of how I felt after my first acquisition (by the V&A, London) 10 years ago. I just want people to know that people like us can be somewhere, and we can make a difference and you can aspire to be there too. If I can do it, I think anyone can, right?

Dan Vo: The other thing is that I hope that it will make people think about supporting Choose Love and refugees, whether it be financially as a donation,or whether it be to think about how they can support people who are new to this country, who are new refugees, and just trying to choose love in an emotional sentimental, real human level as well.

Aida Wilde: Yes, that's so important. I remember when we first landed in the North of England. Back in the '80s it wasn’t known for its great diverse pool of people. But the children there were so lovely, teaching me English, feeling sorry for me and playing with me. I think the most fundamental thing we can do is to just support people the human way. But I also believe that money talks. Money does really talk because it's only with money that we can actually make a difference and get supplies and support to the people who so desperately need them. That's why any art that I create for Choose Love is ultimately just trying to raise as much money and awareness as I can for refugees.

All photographs ©Aida Wilde.

This interview with Aida Wilde was originally conducted by Dan Vo for New Art, New Perspectives, a podcast hosted by the Fitzwilliam Museum. Executive Producer, Hannah Hethmon.

Aida Wilde is an Iranian born, London-based printmaker/visual artist, and educator. Wilde's diverse screen-printed indoor/outdoor installations and social commentary artworks have been featured on city streets and galleries around the world and are responsive works on gentrification, education, and equality. Wilde's academic career includes, associate lecturer, course director and alumni, on the Surface Design and Foundation of Applied Arts at the London College of Communication, University of the Arts (2004-2015). Aida's serigraphs have been exhibited nationally and internationally at institutions including, the Victoria & Albert Museum, Women's Art Library, Goldsmiths, Vienna's Fine Art Academy, Somerset House, the Fitzwilliam Museum, and Saatchi Gallery.

Dan Vo is a freelance museum consultant and media producer. He is Course Leader of the ‘Gap Year London’ programme at Sotheby's Institute of Art; Course Leader of ‘A Queer History of Objects’ at V&A Academy; and Project Manager of the Queer Heritage and Collections Network. Dan founded the award-winning volunteer-led V&A LGBTQ+ Tours and has developed LGBTQ+ programmes for other museums in the UK including the National Gallery, National Galleries of Scotland, National Museum Wales as well as the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Dan is part of the team that opened Queer Britain in 2022, making it the first LGBTQ+ museum in the UK. He has also been a presenter for BBC Arts. (chooselove.org)

Defaced! Money, Conflict, Protest runs from October 11th 2022 to 8th January 2023 at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK.