Myrto Tsilimpounidi: Sometimes academic scholarship and graffiti are not that distinct from one another, in the sense that they both share an attention to words, to detail and to placement. This Special Feature was created in reaction to the different crises occurring internationally, which were reflected in inscriptions on the walls. The different contributions to this collection give us glimpses of these inscriptions in urban environments around the world. Julia Tulke and Konstantinos Avramidis talk about the saturated walls in Athens after a decade of financial crisis, and then six years of what Europe calls a refugee crisis. Oksana Zaporozhets talks about the crisis of self expression and representation in public space in Moscow, while Susan Hansen talks about the visual counter responses to the vote for same sex marriage in Australia. Paridhi Gupta takes us to Delhi and the ongoing struggle for girls and women's presence in public space. Piyarat Panlee joins us from Thailand to discuss the crisis of eviction and gentrification under the military government, and our final stop is in Egypt with Sarah H. Awad's paper on the transformation of Cairo's walls, post-revolution.

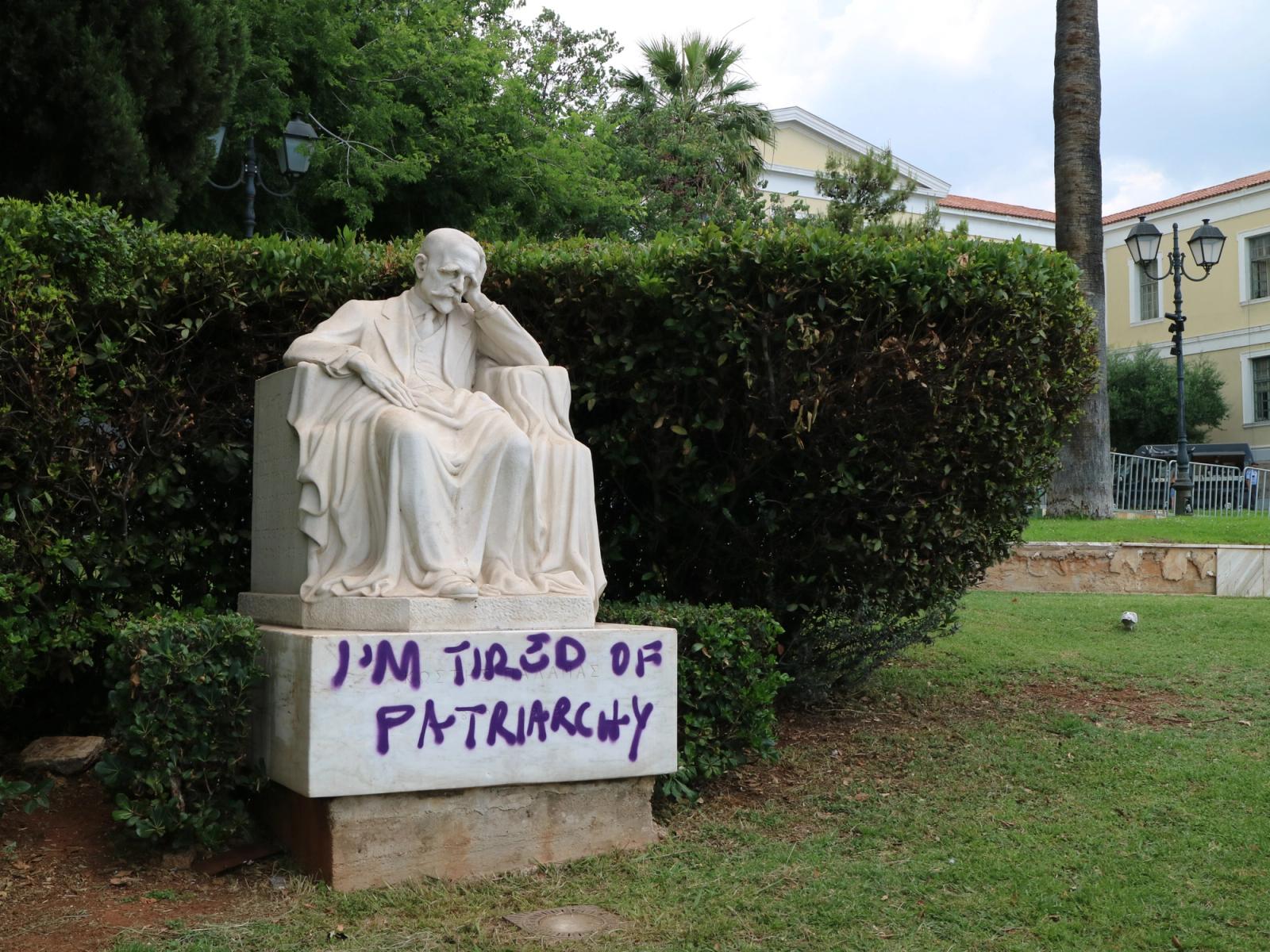

We view city walls as a canvas and the social conditions in different locations as the paint in a gallery of mainly untold stories. What we want to celebrate today is that what is still very much a masculine subculture is experiencing a transformation, not only in the scholarship of queer and feminist perspectives but also in different crews and different writings on the walls.

Anna Carastathis: As a scene, as a practice, and as a body of scholarship, graffiti and street art have long been pervaded by a masculinist culture. We are interested in how this culture might be reworked through an alternative queer feminist lens. How does the approach that you've taken in your own scholarship on graffiti and street art embody a queer feminist perspective?

Susan Hansen: I am delighted to be part of a panel where this is foregrounded, rather than something that I feel we're constantly sneaking in as some kind of underspecified critical alternative. Reading the line in Myrto and Anna's Editorial that said, ‘we are tagging a spot for queer feminist contributions to the academic subfield of graffiti and street art’ made me happy because it's saying something out loud that we all privately say once we've finished our presentations, but that we hardly ever get the opportunity to follow up on. I think one of the things that we have in common is that we are challenging a dominant model of scholarship that valorises the singular artist and the singular photograph of a work as it first appears on the wall. The latter practice is highly problematic because it effectively decontextualises what it is that we're looking at. It takes art out of local sociopolitical context. It doesn't look at what happened next on the wall, and it is very much based on an art historical model of scholarship that looks at individual – and assumed to be male – artists and creates a romantic myth around that. It also encourages a mode of analysing work that's based on practices developed for looking at work in museums and galleries, where you're not allowed to interact with the art. But work on the street is ideally more democratic and participatory than work in institutional art spaces, and I think a lot of our ways of trying to capture this also capture a level of contestation over who has the right to express themselves in public space.

The debates occurring on our city walls echo local and international crises, so it's important that we approach work in public space in sociopolitical and temporal context. I think Sarah Awad and I share an approach to walls as dialogic and as conversational. This is an approach that doesn't ignore the tags or the scrawled comments on the more beautiful or monumental pieces, and in fact also looks at the practice of negative curation, erasure, and buffing as an integral part of the conversation – whether that's a local person taking offense to a work and painting it over themselves, or whether that's a zero tolerance top down approach from the authorities that seeks to erase everything. Erasure has to be part of this conversation.

Anna Carastathis: Piyarat, what are your insights on this question?

Piyarat Panlee: I think creativity has long offered an alternative lens for proposing solutions to some of the world's most pressing issues. In recent years in Thailand, there have been grassroots movements, civil society organisations, activists, social workers, teachers and academics and others across the country working hard to urgently discuss important issues related to the crisis with the feminist queer and decolonial lens. This movement has challenged political homophobia and anti-feminism locally through policy intervention, street demonstrations and digital activism. The movement also seeks forms of expression and political action that critique structures of sexism, heterosexism, patriarchy, and misogyny. A queer feminist perspective is based on the recognition that gender and sexuality are not only central to any understanding of a wider social and political process, but also are always brought forth in complex intersections with other social inequalities and conditions. We should also expand upon this perspective to analysepower structures through the lens of intersecting social divisions such as racialisation, gender, and sexuality in our current political context.

Anna Carastathis: Julia, what are your thoughts on a queer feminist perspective?

Julia Tulke: I wanted to start by saying something more generally in response to this question, which is that I think employing a feminist queer perspective is really about becoming space invaders. And I say this with reference not to the French street artist Invader but to a 2004 book that some of you may know by Nirmal Puwar, that's called Space Invaders: Race, Gender and Bodies Out of Place. In this book, Puwar describes a dialectic between what she calls the somatic norm and the space invader, and I want to quote her here, because I think this is really insightful with regard to this question. Puwar says that ‘social spaces are not blank and open for anybody to occupy. While all can in theory enter, it is certain types of bodies that are tacitly designed as being the natural occupants of specific positions. Some bodies are deemed as having the right to belong while others are marked out as trespassers who are, in accordance with how both spaces and bodies are imagined, circumscribed as being out of place. Not being the somatic norm, they are space invaders. Their arrival brings into clear relief what has been able to pass as the invisible, unmarked and undeclared social norm.’

There are echoes here of the notion of graffiti as something out of place in a more general sense, but I think this idea of the somatic norm and the space invader are immensely generative when we think about a feminist queer perspective to street art and graffiti scholarship practice, because they help us to decentre one of the most enduring and frustrating normative ideas about street art and graffiti, which is that the general anonymity of these practices somehow renders embodied identity irrelevant. There's this idea that there is a distance between the body of a writer, the body of an artist, and the trace that they leave on the wall, and by virtue of that, somehow this trace ends up transcending race, class, gender, and so forth. There is also in turn this romanticised notion that writing on walls is somehow inherently democratic and that those are somehow inherently the marginal stories. But if we look more closely at who actually participates, who benefits, and how the risks and benefits are differentially distributed among lines of race, class, gender, and so forth within this practice – as they are in any other context – then I think we can get at a more queer feminist embodied understanding of the practice.

For me, as a visibly queer feminist scholar, educator, photographer and practitioner, I feel like I do take on the position of space invader. Any encounter I have with the field always forecloses certain conversations and enables others. I haven't yet explicitly written about what my particular body inhabiting this field forecloses and opens up, but I hope at some point I can, and maybe this can be a starting point. I hope to reflect on these issues in more of a collaborative setting. So, I hope that today we can function as an assembly of space invaders and start addressing some of these questions.

Myrto Tsilimpounidi: Let's accept this invitation. Our next question is about the relationship between crisis and urban inscriptions in your work.

Paridhi Gupta: The crisis of gender is central to my case study. But primarily it is about the crisis of not belonging in a space, and to bring in Julia's points, it's about being made to feel like you constantly do not belong in a place, and what happens when as artists you come into that space and take up that space? We often think of graffiti as just the end product. We do not think of the process of making it. My project is about young women in a marginalised urban village in the capital of India. Some of them are immigrants from war torn countries, from marginalised nations, from marginalised castes, classes and gender identities, and they've found community within an art group.

They created murals which centre on women enjoying public space. This image is so intuitively opposite to what they see around them, which is a space occupied by males and traversed by males. However, the point is, it is not just about the image, it's about the time that they have spent in creating that image. They have occupied a space where women are not even speaking, and women are not even seen. What happens in the process when as young women, and as visibly gendered bodies, they enter this space and occupy it for a lengthy amount of time to paint? And what is the discomfort that they create around them? What is the reaction they get from passersby and how do they deal with it, and is there a positive sense of belonging that comes as a result of this occupation?

Konstantinos Avramidis: In relation to my piece for this special issue, although it relates to two crisis moments in the periphery of what we call geographical Europe, I see in this an opportunity to approach crisis as a form of critique of the very means of space production, which we often take for granted. Through my architectural training and background, the aim was to underline the hegemony of spatial production and architectural representation itself. So, this crisis of representation in the public domain becomes a critique of the means of representing a space, and effectively there's an attempt to bring into representation this much needed multifocality of what it means to be present and to express yourself in public space – and to bring these voices of different crisis moments together, so they are speaking to each other.

Oksana Zaporozhets: I would like to express my gratitude to Myrto and Anna for dedicating this special feature to the memory of my dear coauthor and friend Natalia Samutina, who was one of the pioneers of graffiti studies in Russia. Thank you Natalia for all our adventures and collaborations. We really miss you.

Today we take the wide geography and diversity of graffiti and street art studies for granted. But it was not like that for many years. I'm grateful to have the opportunity to discuss graffiti from Russia. In terms of the connection between graffiti and street art and crisis, we argue that it is not only the content of graffiti or street art that reflects crisis, but also the very presence of graffiti and street art inscriptions in the city. The absence of graffiti and the quick removal or buffing of graffiti from the streets of Moscow is a symptom of crisis. In many other cities all over the world the presence of street art and graffiti gives us a sense of the normality of urban life and indeed becomes iconic for some cities. But for many years it has not been like this in Moscow, because graffiti and street art are now rapidly erased, and at some point the state and neoliberal agents started replacing these organic urban inscriptions with large commissioned murals. This changed the whole picture for us because urban space became occupied by these monumental agents.

In our paper we focus on the presence of small urban inscriptions. These small-scale inscriptions matter as they bring public discussions back to the street. Today, the Russian anti-war movement is using small scale inscriptions to print messages on the walls, on bank notes, and on price tags in shops. They use these very small inscriptions to publicly register their opposition to the war. Our case study focuses on the idea that it's not the presence but rather the absence of urban inscriptions that represents crisis, and that Moscow's zero tolerance policy has led to small scale inscriptions becoming the barometer of what people think, what people want, and what they are eager to discuss in their reactions to our present situation.

Sarah H. Awad: Thanks for creating this space where we can have a dialogue, share ideas, and build on each other's thinking. My field work in the article was based in Egypt and when I think about space and inscriptions of crisis in the city space, I think of how on a more general level power dynamics, our social relationships, who's represented and who's not represented, are always spatialised and they are always present in the spaces we live in. And they become more explicit in cases like Cairo and the Egyptian revolution, where new inscriptions appear that proclaim space in a certain ways that were not accepted before.

Power has a monopoly over visual representation in the city. For many years it's not just that the only images you see are advertisement images or images of authority, but also how that authority is represented. Here, we see only one version of the authority figure, as untouched and young and as the father of the nation. And then we see the counter images of the revolution breaking away from this and providing another version of reality. But in my own work, as in Susan's work, the idea is that when we follow those images and inscriptions in the city as some form of a social dialogue and some form of responses to each other – some reproducing certain visuals, some refuting them – then we find how power is spatialised and contested in this space. In the case of Egypt, we could see it in this cycle of the protest movement taking over, but also the counter protest and governmental forms of erasure, and in the form of the government's own urban inscriptions. They were writing on city walls, ‘the wall is not the place for your opinion,’ So, we look at that dialogue. My more general point is how much power dynamics and representations are always spatialised in the places we live in, it's just that sometimes we do not see what's not represented, so we don't see the absences or who's not represented in spaces.

Susan Hansen: The crisis that I looked at was centred aroundthe recent postal vote for marriage equality (or same sex marriage) in Australia. I was drawn to this because I'm Australian and because I'm queer and also because I'm interested in the consequential dialogue that happens on the walls of our cities. What happened was that during the six week campaign before the actual vote for marriage equality, the rate of homophobic hate speech dramatically escalated. This has since been described as an acute external minority stress event for LGBTQ+ people and their allies in Australia. Notably, this hate crime also took the form of graffiti and other visual works in public space. In this case study I looked at both homophobic graffiti against marriage equality, and the subversion of and resistance to this hate speech in urban inscriptions in public space.

This postal vote put the human rights of one minority group on the agenda, as if the majority had the moral right to decide whether they should share the rights they already enjoyed. And this seemed to release a lot of homophobic public sentiment, the volume which was palpable in the media and in public space. What I was interested in were the ways that some people responded to this crisis by subverting this hate graffiti or by erasing it – or engaging in negative curation. I documented the graffiti and street art during this period using repeat photography, or longitudinal photo-documentation. This method allows us to unpick what happens to these spaces over time in this ongoing debate. I was also interested in the inverse of this. At the time, the Christian right was encouraging their followers to paint bomb or erase pro marriage equality murals. I used repeat photography to capture both the actions of the paint bombers and the evangelistic buffers, and how people responded to the buff as an invitational democratic surface that reinforced and affirmed the rights that were luckily borne out in the vote.

I also collected video recordings of attempted erasures in process, and captured people challenging those who were trying to buff pro marriage equality murals. So, I had two different data sources. Two different ways into the crisis – one over time, and one in the moment of attempted erasure. This can show us what happens when somebody tries to erase something from the public visual landscape that they are ideologically attached to, and how that is challenged, how that is resisted.

Anna Carastathis: Let's move to the third question, which brings into the present the visual essays which you all began writing nearly five years ago. Of course, a lot has happened since, and we were dealing with crises that were unfolding at the time of writing. These crises – some of them declared, some of them undeclared – were urgent, and often mortally violent, but they were seen as temporary conditions. We are wondering how you would now reflect on the urban conditions that were unfolding then? And how your perspective has shifted over the last five years?

Piyarat Panlee: It's sad to share that five years later, nothing much has changed in Thailand. We still ended up with a military-led government. And you know this kind of government – we can't expect much, right? Thailand is in the midst of a transformation from a predominantly rural country to an increasingly urban one. In as little as ten years, the country has shifted from 36% urban to almost 50% urban, which means that half of the population now lives in cities and urban areas. While Thailand's urbanisation rates are still low compared to other developed nations, this transformation in Thailand is still significant, especially as most of the growth is expected to occur in Bangkok, the capital city. This development will place increasing demands on urban infrastructure as the city grows and grows.

The eviction of communities is part of a wider effort to modernise Bangkok. Authorities are also creating sidewalks of vendors and food stalls and they are removing homes along the river to build a promenade. The evictions mostly target poor communities who have no formal rights over their land or property yet are an integral part of the city and contribute to its economy and ‘colourful’ character. Beautification is being worked up as a justification for urban redevelopment that threatens existing ways of life and ignores the aesthetic values and social needs of the poorer residents. They are being sacrificed on the altar of the touristic experience. It is a tragedy for Bangkok and for Thailand. Thai society has become irreparably divided by the interests of the ruling elite. The military-led government's urban development plans aren't just about the economy. The city itself is being reorganised against the poor and their politics. The Covid-19 outbreak and related quarantine and recovery measures and policy responses have exacerbated inequalities in the city. These have increased urban poverty and deepened the inequalities that existed before the Covid-19 outbreak.

Sarah H. Awad: Like Piyarat, I also don’t have good news. In 2013, my idea was to look at the Egyptian social movement's work on the street from the revolution. But it was some years until I got to do my PhD, and by then everything had been erased. That was actually what guided me to the idea of looking at the social life of images, because it was not just a situation of some images being erased. It was a situation of counterrevolution. It was a situation of great loss and grief from the activists and grief for a future where things could have been different. Many of the activists were imprisoned or died. So, this led to the idea of looking at the social life of those images – maybe those images live on, and they have other spaces to live on in, and they are documented in some way.

Even during my PhD, you could see these protest images transitioning from being large pieces, to only being able to be quick stencils, because of the risk of using public space for political messages, and then finally transitioning into online spaces. One other thing that's different from five years ago is that even the online space is quite threatening right now, so images that mock the President are targeted, and mobile phones are checked randomly in the street. This leaves me a bit pessimistic about the situation today, but I do think those ideas still live on in more hidden cultures and hidden spaces now, like James Scott's notion of hidden transcripts. But there is less and less space for expression. Making art as a form of social and political action has become, not only for me, but also for the street artists that I have talked with, a matter of weighing up the value and the potential impact of the work against the risk to people's own personal lives and families. The risk extends beyond the artist to their family.

Something that caught my attention with Piriyat's discussion of the situation in Thailand is her observation that the city spaces are being renovated. In Cairo, it's also now very much controlled and renovated – there's fresh paint everywhere and many more cameras. So, we can see power very much spatialised. Those who support this development see it as beautification. They see it as evidence that we're finally moving away from the chaos of the revolution.

I will end with the words of one of my participants, who labels those kinds of creative beautifications and renovations all around the city – and especially in the central areas of the protest like Tahrir Square – a cover up rather than a beautification. It's like when you do a crime, you then need to cover it up and push it under the carpet. My academic attention is more and more focused on the idea of the spaces of absences and of what used to be, and the continued presence of absence in spite of the many efforts to cover it in so many layers of beautification.

Paridhi Gupta: I would like to build this connection between crisis and inscription and ephemerality. We understand that both the crises and the inscriptions that we're talking about are ephemeral. A crisis, at least in my case, of the community street art project in Khirkee is a continuous everyday rupture – every time you encounter the space as masculine, every time you encounter the space as visibly empty of women, that crisis reoccurs – it's an everyday rupture. Inscriptions as a response to this rupture create a disjuncture in this masculine space. They initiate a conversation.

In my paper the response to the first form of rupture has been to delay the ephemerality of the other. To somehow protect it against human erosion because there is this idea of reaffirming belongingness, to continue the stake you've claimed for as long a period as you can. When a mural is whitewashed, the group feels sad. They feel that a move that they had made forward is being pushed a step back, so they want to delay this ephemerality. They want to protect their art, at least from human factors of erosion, and that act of protection then becomes a way for them to resolve the crisis of not belonging. For young girls it is an extension of staking claim to space and holding on to this very temporary intervention that comes with street art and community art projects.

Over the past five years, the space itself has not changed. It has not yet gentrified like other urban villages in Delhi. But the act of making street art gave this group confidence. When I was talking to the artist who initiated this project, she said that now these young girls have started going out in the area at night, which is a huge thing for them. They have felt so threatened, as space invaders, just because of their gender in public space. Some of them have also encountered racism. But now these young people are the flaneurs.

Oksana Zaporozhets: I think the topic for the next special issue should be street art and graffiti in authoritarian cities. The situation is not getting any better in Russia where it's marching from authoritarianism to totalitarianism. I would like to stress two points. Firstly, that the history of graffiti and street art and their presence in the city is really important because it's not only the images which are erased, but it's also the stories of their creators and the public dialogue attached to it, which are also erased from the city streets. Secondly, I’d like to highlight non-hegemonic counternarratives. It's important to look not only at those messages that are in direct opposition and which overtly resist the present situation, but also to remember that the very presence of unsanctioned images in public space could be considered as resistance.

Several years ago, the streets of Moscow were covered with these pictures of faces and people were puzzled. They could not understand what it meant. It's a simple image of a face which consists of a circle and a couple of spots. So, it's difficult to interpret. We assume that it's a face but we don’t know if it's a human face. Or what the expression on the face is, is it happy, is it sad? In our urban spaces we have the right to understand and to identify the actors or the messages, but we also have the right to not understand. To be puzzled in this way means to be involved in the dialogue in urban space – to be curious about who created the image and what it means, and how I should react to that. The commissioned murals in Moscow's urban spaces are quite direct, there's a definite message praising military masculinity. In contrast to these monumental murals, street art that actually involves and troubles and puzzles you, includes people in the dialogue and makes you think about the city, the public, and your role in urban space.

Konstantinos Avramidis: I think it was Ley and Cybriwsky who said that graffiti are the headlines of tomorrow's newspaper. Street art is destined to follow what is happening around us – we’ve witnessed this most recently with graffiti responses to Covid-19. Despite the fact that we now live in hyper technological and saturated technological environments, this low tech form of expression and community still matters. In the last five years, some street artists have left the scene and moved on, having made a name for themselves with iconography that reflected the economic crisis. But of course, the scene has also changed – not in terms of intensity, but there has been a drop in terms of numbers. In terms of urgency, things are getting more mature, despite strong municipal attempts to promote normalised beautified murals. In my architectural drawings for this special feature, I try to capture and render visible these palimpsests, writing over writing, erasing, the constant remaking of the nature of our city's surfaces, and the affinities these writings share across epochs and eras. In a sense I was creating a dialogue with Susan and Sarah's methods of repeat photography, just on a completely different time scale – my work covers several different decades and different crisis moments.

Julia Tulke: My work is also grounded in Athens. Since 2013, I've had a project called Aesthetics of Crisis that has documented graffiti and street art in the context of the crisis in Athens.Athens has long been considered one of the most graffiti saturated cities in Europe. This is closely related to the abandonment of graffiti removal, both on the part of the municipality and on the part of private business owners. Crisis and austerity and graffiti and street art are closely interlinked in the context of Athens.

If that has been true for most of the 2010s, then at the end of this decade, with a governmental transition towards a new liberal conservative city government, there has been a distinct shift to graffiti removal – or negative curation – as an aspirational way of performing the end of crisis.

Everyone who has looked at graffiti and street art in Athens will know this quote from Amalia Zepou from 2014, where she says, ‘if the city is in crisis, if it has collapsed, you’ll have graffiti everywhere, but once graffiti becomes commissioned, it's a signal of a beginning to the end of the crisis. ’The current administration of Athens has taken this statement and made it into a policy paradigm. They're fully embracing commissioned beautification-centric street art as a means of ameliorating the visual appearance of public space, by removing ‘visual pollution’ and the ‘smudge’ of graffiti and uncommissioned street art from the city, as a signal to the end of the crisis. It's interesting to look at the kinds of discourses they draw on to justify this. It's about the return of control to public space. Crisis and austerity signify a retreat of control from public space, and now the administration is signaling a return. In these campaigns you see an insistence that there is a renewed presence of the municipality on the streets of the city, and they also draw on the old school moral panic discourses about graffiti from NYC in the '70s. The Mayor has spoken of graffiti removal as ‘removing misery’ and has asserted the ‘right to live in a city with clean public spaces.’

There's also a more contemporary association with the sanitation of public space in the context of Covid, so it's interesting to think about how these discourses morph and adjust to newer crisis situations. If we look on the ground, these graffiti removal campaigns are actually not very successful. I think we can argue that removing graffiti or negatively curating public space is an impossible venture. But I don’t think these campaigns are actually about making space free of graffiti, they're about using graffiti as a vehicle to symbolically claim the end to crisis. So, this is where my attention has turned at the end of a decade of thinking about street art and graffiti in the context of crisis.

Ulises Moreno-Tabarez (City Editor): I'm curious about how your methodological approach to studying street art has changed over the last five years?

Julia Tulke: For me, things have shifted from thinking about street art and graffiti as an object of study towards thinking of street art and graffiti as a method of studying space more broadly, and I think that's echoed in a lot of our contributions here. In moving away from object-centric approaches to site specific approaches, Susan's work on the method of longitudinal photo-documentation has been influential. This is essentially the idea of not centring so much on a single snapshot of an object as the object of analysis but repeatedly returning to sites to document them and thinking about sequences and dialogues. And this is how I've come to think of my engagement with Athens, because I've been returning to the city since 2013. Every time I come, I continue to document and I continue to think about changes. This is the prism through which I now think about my own scholarship.

Susan Hansen: In terms of the evolution of my own methods, I came to this originally as a trained conversation analyst, so I see dialogue in images. So, I tried to find a way to capture what I was looking at that slowed the conversation down, and this is where the method of longitudinal photo-documentation came from. Even though work on the street is an asynchronous form of visual communication, it still temporally unfolds and responds in a lot of the same ways that verbal forms of dialogue do.

You've just got to string it all together retrospectively to re-embed it in sequence so that you can then analyse it. But over the last five years, I've had less time to spend on developing this methodology because I'm currently functioning as more of an academic midwife, in that I now spend most of my time developing, curating, editing, and promoting the work of others. But I am hoping that we can take these methodological developments forward together.

Sarah H. Awad: I also think that our methods have changed from looking at objects that exist, to the stories of things that do not exist anymore, and the social life of what started in different narratives. But in authoritarian cities, engaging in this kind of investigation can not only threaten active political activists on the ground, but also journalists and academics. To be totally honest, this threat has discouraged me from taking on more field work and interviews and photo-documentation in Cairo. Egypt is a place where just carrying a camera could get you into a lot of trouble. So, my primary place of data collection has transitioned in response to this political threat. I now use the methodological framework I developed in Cairo on cases elsewhere. I am currently applying this to right wing political campaigning in Denmark, looking at the process of othering through images in posters and graffiti about the refugee crisis.

Paridhi Gupta: I also study political graffiti and feminist political movements as cultural interventions in the city. I feel that increasingly the city is becoming unsafe for the gendered body of the researcher. My methods have also transformed in that I no longer carry a digital camera. Even though we live in this very developed world of beautiful images being created with DSLRs, not everyone has the privilege, nor the ability to carry big cameras in public space, especially when we're going into active movements as women. So, we need to make a case for low resolution images being legitimate objects of research.

Piyarat Panlee: I started writing my paper from the point of view of an anthropologist using visual research methods.But recently, my interests have shifted more to visual anthropology and community-based research. I have started using the photovoice and photo elicitation method, which has given me insights into the community that I might not find through interview methods.

Oksana Zaporozhets: I feel that my approach has also changed in that it's moved from an isolated study of a particular city to a more comparative perspective. I am grateful to the Thai and Egyptian cases because they resemble the situation in Russian cities. I think it's really important not to exoticise the individual cities we study, and to put things in a broader context. Thank you so much for this discussion. It inspires me to continue our research.

Myrto Tsilimpounidi: Before we close, I want to acknowledge the queer feminist artists and crews. You know who you are. In essence they've told me everything I need to know about space, about community, and about writing, and I want to celebrate this feminist approach to graffiti and street art. Without this movement we wouldn't be here today. Whenever we arrive in a new city, other than following the inscriptions on the walls, we connect with each other. It's a way of understanding and viewing the city through collective eyes, through a collective lens, through collective opportunity.

Konstantinos Avramidis is a Lecturer in Architecture

and Landscapes at the University of Cyprus. He has taught extensively at various institutions in Greece and the UK,

most recently at Drury University and the University of Portsmouth. His research has been published in books and journals, including City and Design Journal. Konstantinos co-founded the architectural design research journal Drawing

On and is the principal editor of Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City (Routledge, 2017).

Sarah H. Awad is Associate Professor in sociocultural psychology at Aalborg University, Denmark. In her research,

she explores the processes by which individuals develop

through times of life ruptures and social change using art

and storytelling. She has also a special interest in visual methods and the analysis of urban images and their influence on identity, collective memory and politics within a society.

Anna Carastathis is a political theorist. Anna has held research and teaching positions in various institutions in Canada, the United States, and Greece (Université de Montréal, California State University Los Angeles, University of British Columbia, Concordia University, McGill University, Panteion University of Political and Social Sciences). She is the author of Intersectionality: Origins, Contestations, Horizons (University of Nebraska Press, 2016), which was named a Choice Outstanding Academic Title by the American Library Association, and Reproducing Refugees: Photographìa of a Crisis (co-authored with Myrto Tsilimpounidi, Rowman & Littlefield International, 2020).

Paridhi Gupta has a PhD in Gender Studies from Jawaharlal Nehru University, India. Her doctoral work focussed on the cultural manifestations of contemporary feminist movements in India and their relationship to urban spaces. She is interested in visual interventions into cityscapes and has looked at forms of political art and community art in India. She is also one

of the editors of an independent journal ‘EnGender’ and works towards making academia inclusive and accessible through her peer support group.

Susan Hansen is Chair of the Visual and Arts-based Methods Group at Middlesex University, London. She is interested in graffiti and street art's existence within a field of social interaction – as a form of conversation on urban walls that are constantly changing. She is Editor of Nuart Journal, Co-Editor of Visual Studies, and Vice-President of the International Visual Sociology Association.

Piyarat Panlee is a Lecturer in the Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Kasetsart University, Bangkok, Thailand.

She obtained her PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Sussex, United Kingdom, in 2020. Her current project focuses on the links between visual culture, politics, place, branding and dark tourism. Her latest paper is ‘Daring to Resist: Material Culture of Social Movement in Thailand after the 2014 Coup d’etat’, in The Journal of Anthropology, Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre (JASAC).

Myrto Tsilimpounidi is a social researcher and photographer. Their research focuses on the interface between urbanism, culture, and innovative methodologies. They are the author

of Sociology of Crisis: Visualising Urban Austerity (Routledge, 2017); co-author of Reproducing Refugees: Photographìa of a Crisis (Rowman & Littlefield International, 2020, with Anna Carastathis); and the co-editor of Remapping Crisis: A Guide

to Athens (Zero Books, 2014) and Street Art & Graffiti: Reading, Writing & Representing the City (Routledge, 2017).

Julia Tulke is a PhD candidate in Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester, NY. Her research broadly interrogates the politics and poetics of space, with a particular focus on crisis cities as sites of cultural production and political intervention, for which Athens has been her central case study. Her work on the city through the past decade includes research and writing on political street art and graffiti, austerity urbanism, crisis photography,

and the emergence of feminist and queer protest. Cumulating and concluding these endeavors, her dissertation traces

the proliferation and significance of artist-run spaces and initiatives during the historical period bounded by the 2008 economic crisis and the 2020 pandemic emergency.

Oksana Zaporozhets is a visiting researcher at the Insitute for Regional Geography in Leipzig. Her current research projects focus on urban inequalities, new residential areas

and large housing estates. Her research interests also include street art and everyday mobility. She co-edited the books Microurbanism: City in Details (2014) and Nets of the City. Citizens. Technologies. Governance (2021).

Carastathis, A. & Tsilimpounidi, M. (Eds, 2021) Inscriptions

of Crisis: Street Art, Graffiti, and Urban Interventions,

in City: Analysis of Urban Change, Theory, Action, 25: 3–4.