The introduction to your new book describes you as a consummate scavenger. You've been dumpster diving all your adult life, mostly for the kind of stuff that is useful or valuable. But in this case, you've found or rescued a collection of photographs. How are discarded photographs of people you’ll never meet useful or valuable?

Jeff Ferrell: That's a really good place to start. I'll begin by saying that at no point over the last 40 years have I set out to ‘rescue’ the photographs. My goals as a dumpster diver have been anarchist direct action, and taking charge of my own life; an environmental intervention to try to keep things out of landfill; and certainly a kind of resource redistribution away from the privileged. So, as you say, that means that I'm looking for things that are useful to people or things that have ecological value by being saved. But in doing that over and over again, these photos popped up, layered into shoeboxes that were then thrown away or old photo albums. Sometimes they were just loose with other kinds of trash. And so being who I am and interested in the visual and street art, about 20 years ago I began saving them with some care, and now I have many thousands from dumpster diving here in the affluent neighbourhoods of a city in the United States.

So, you've accumulated a massive corpus of these photographs over time, yet the collection in the book is not huge. How did you select the photographs that ended up in the book?

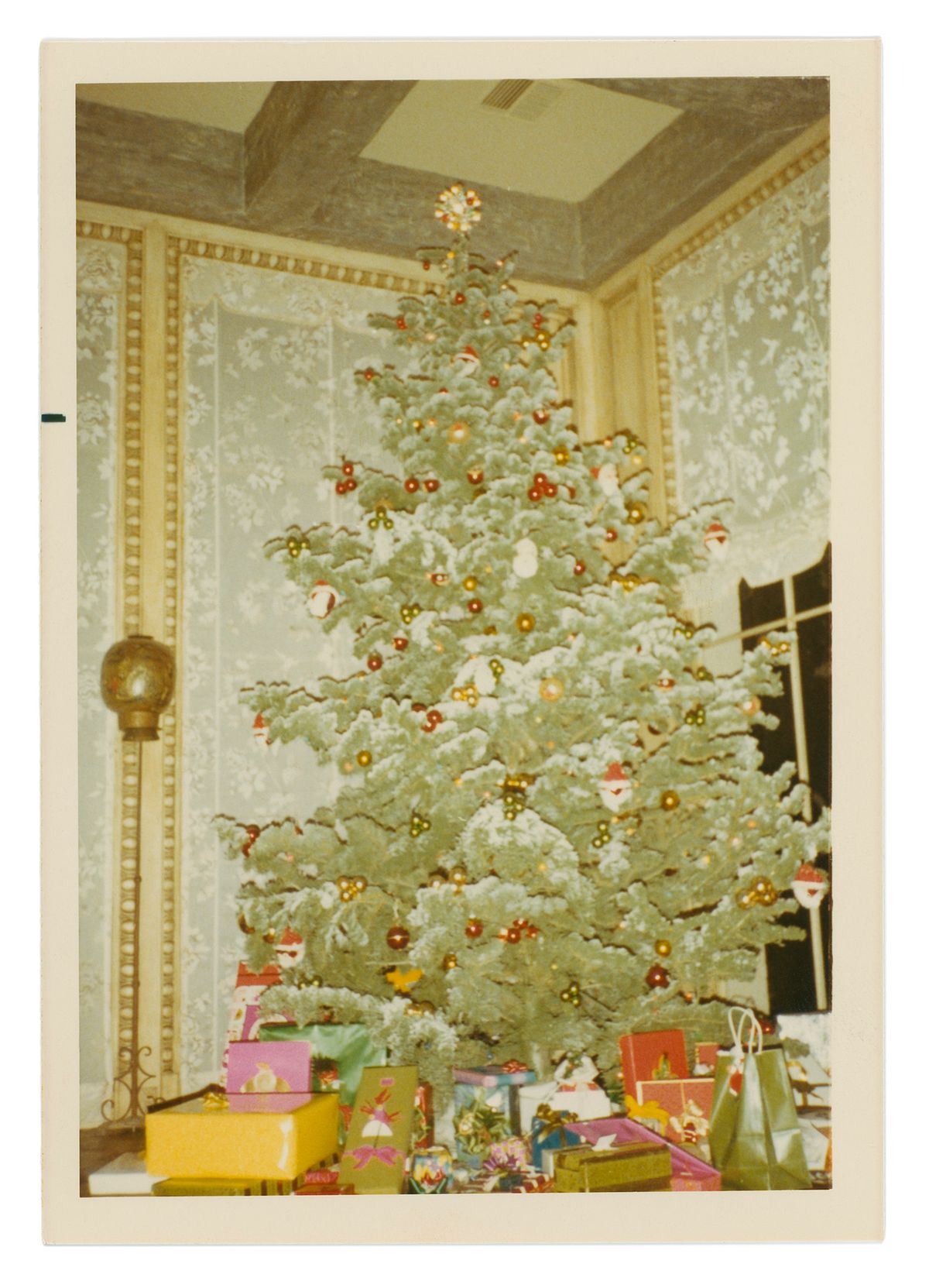

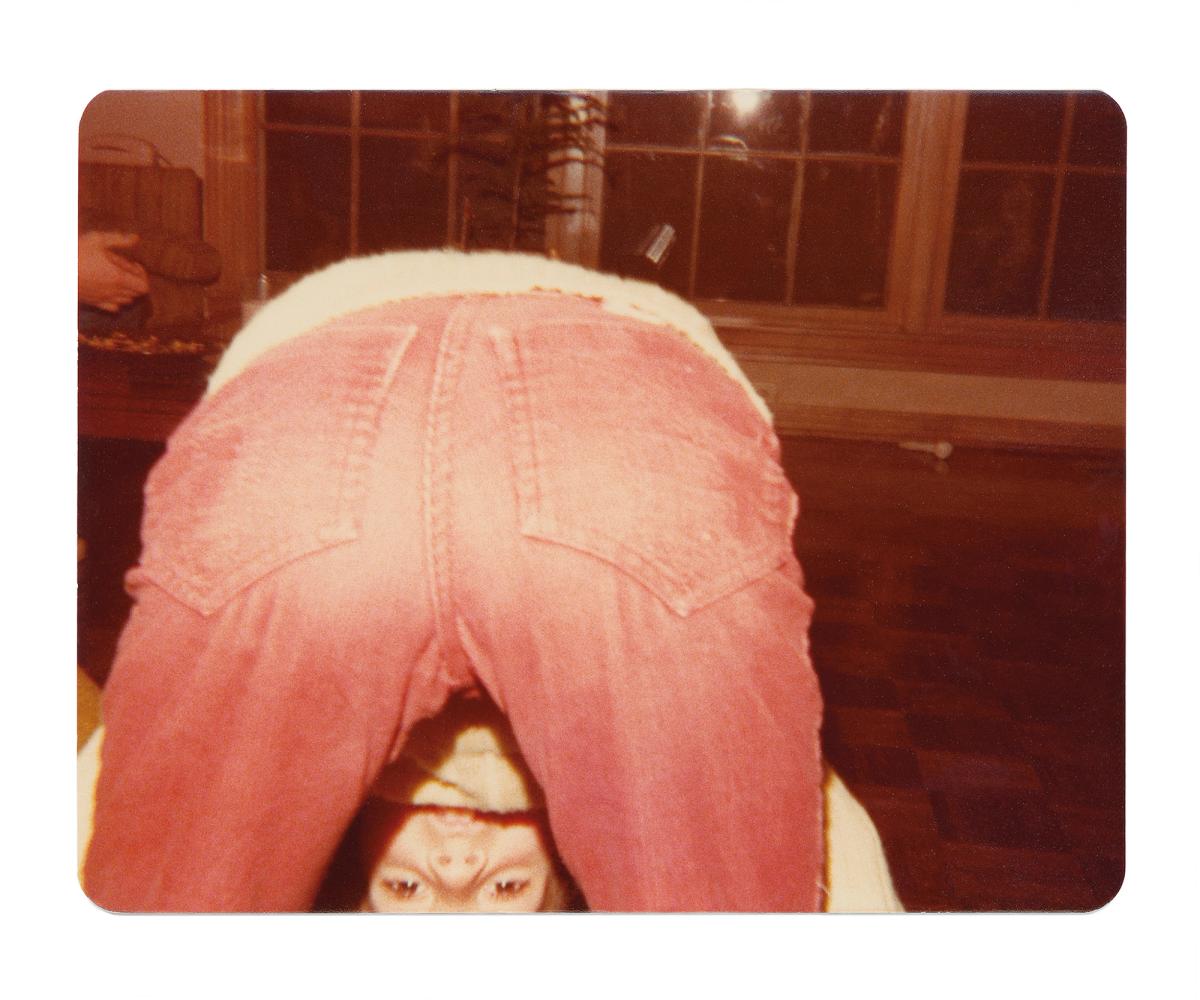

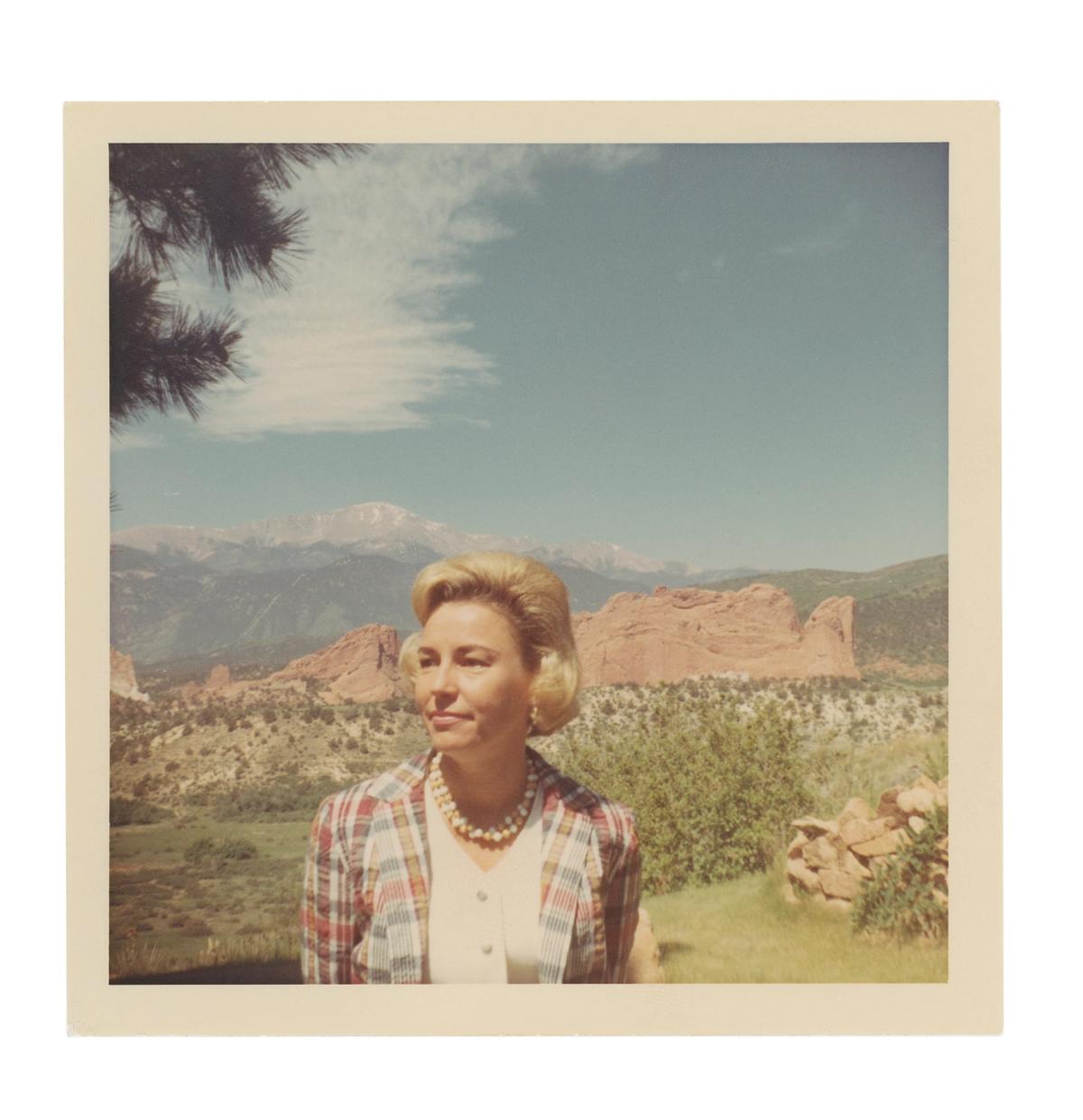

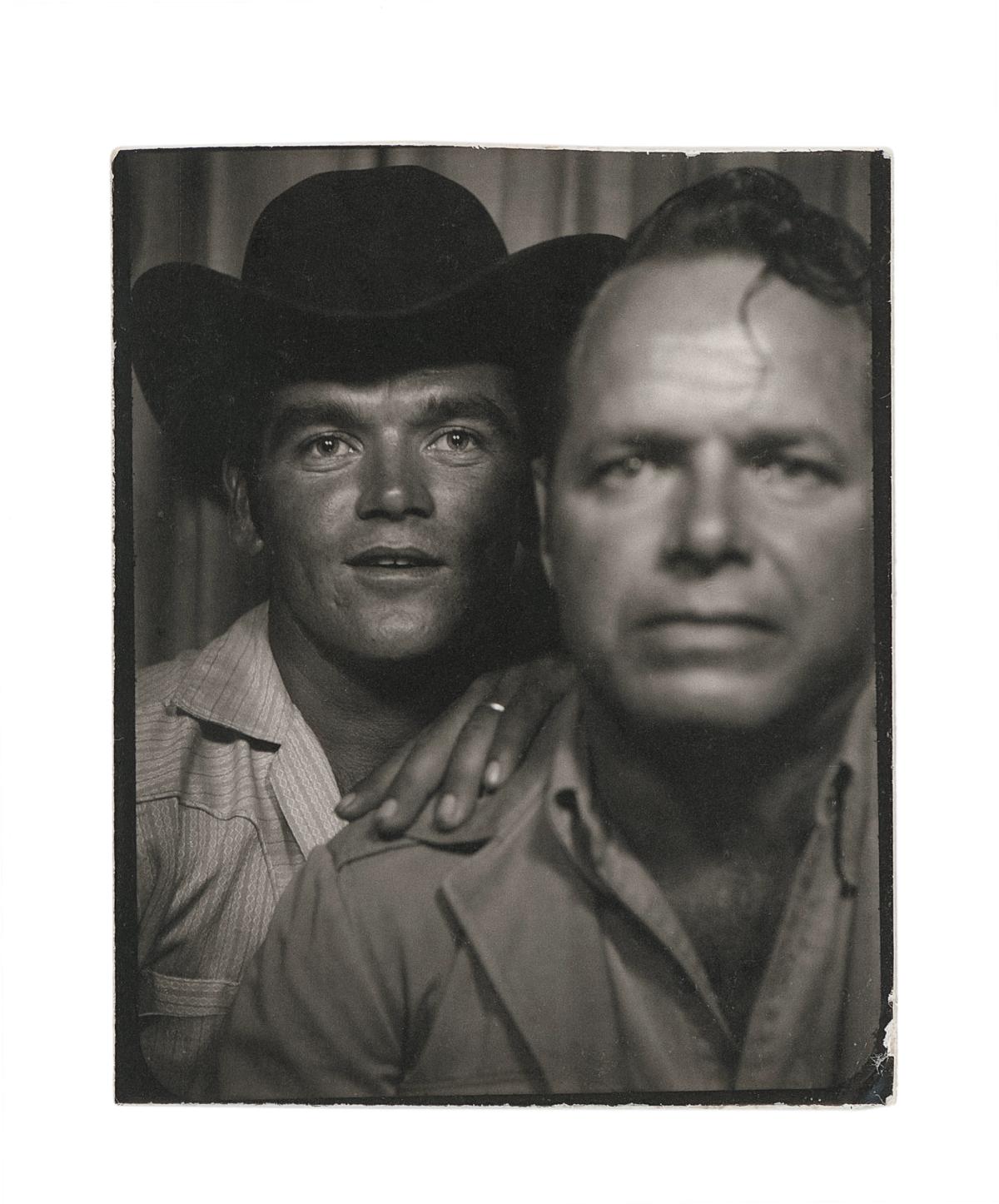

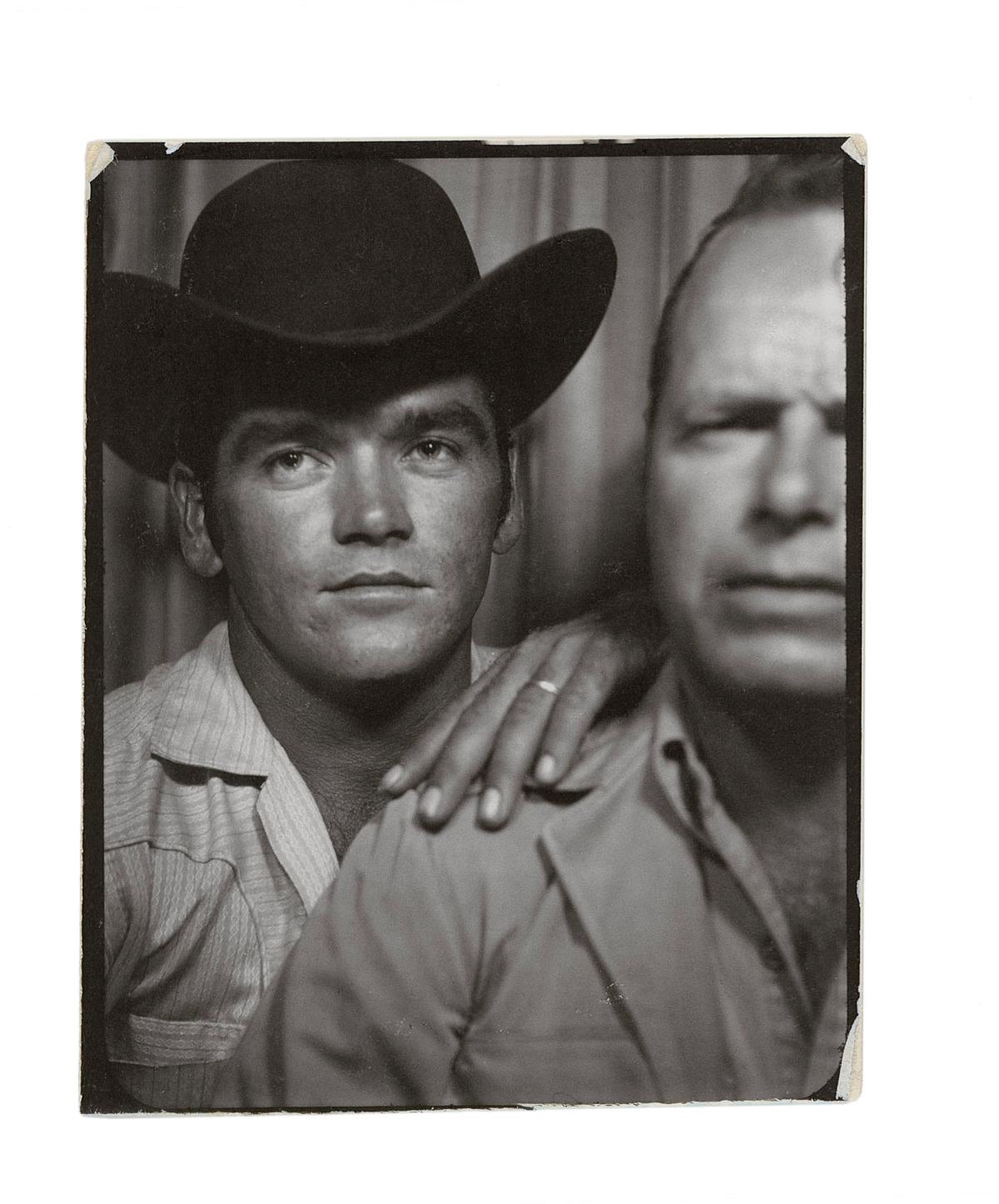

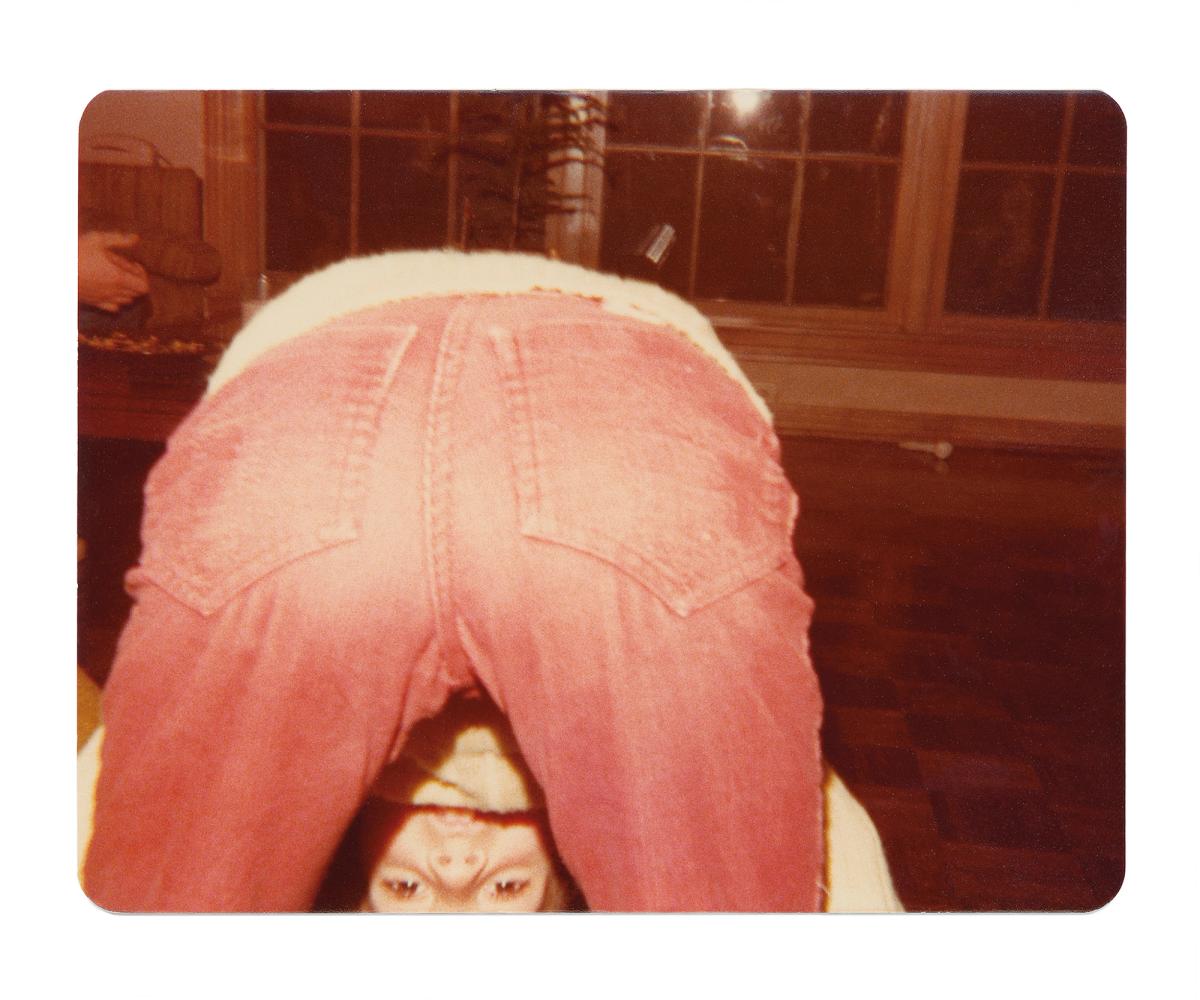

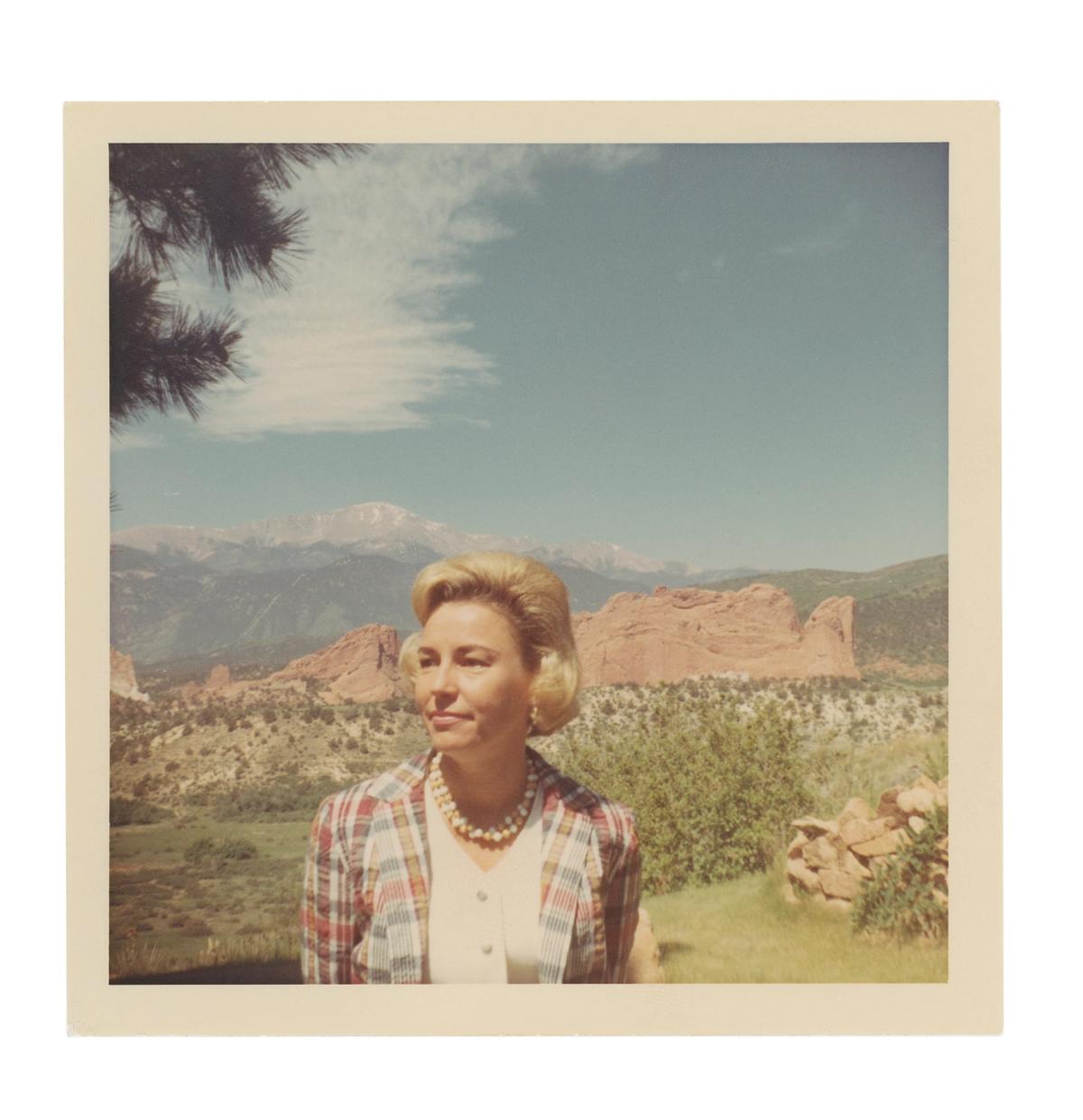

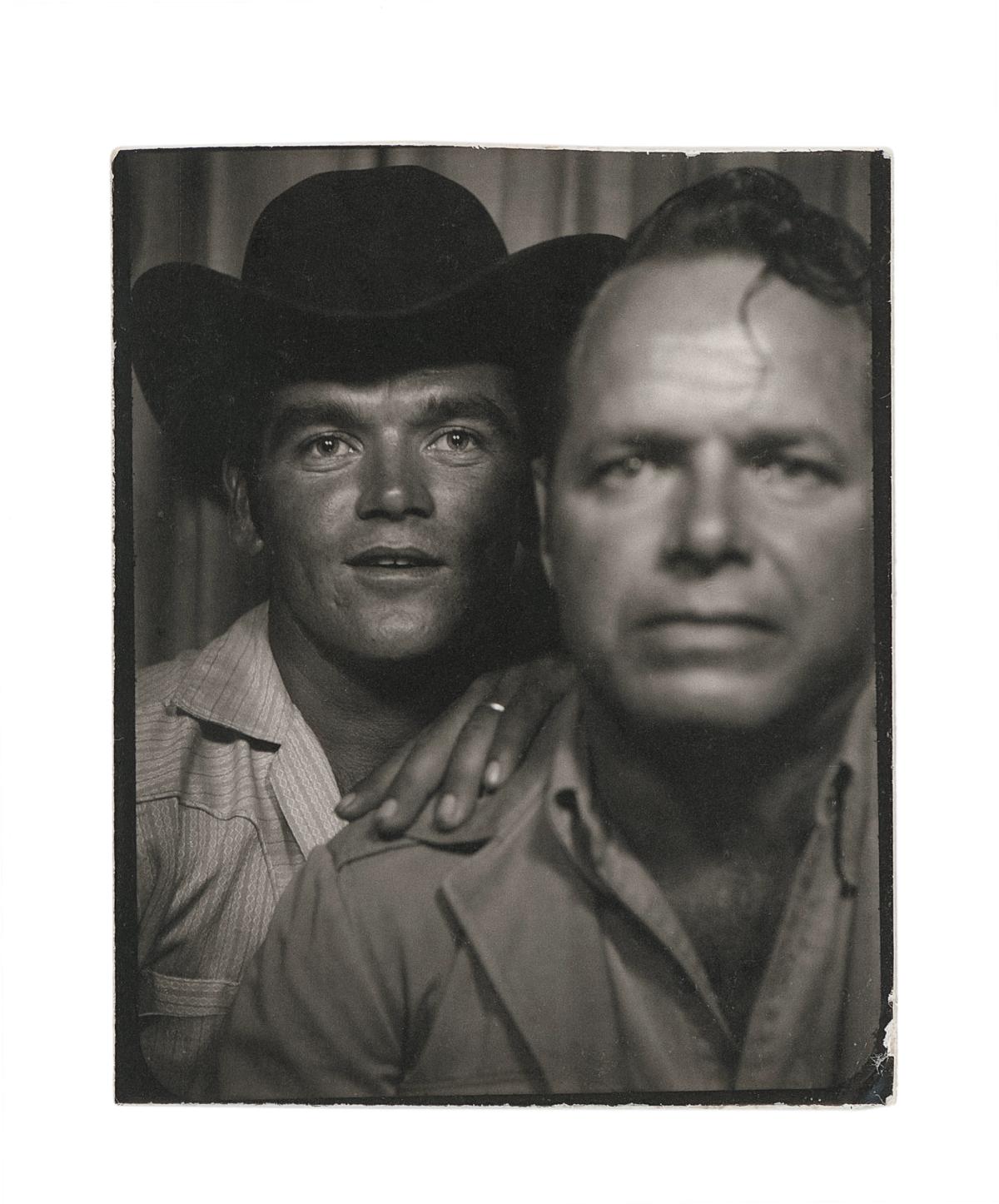

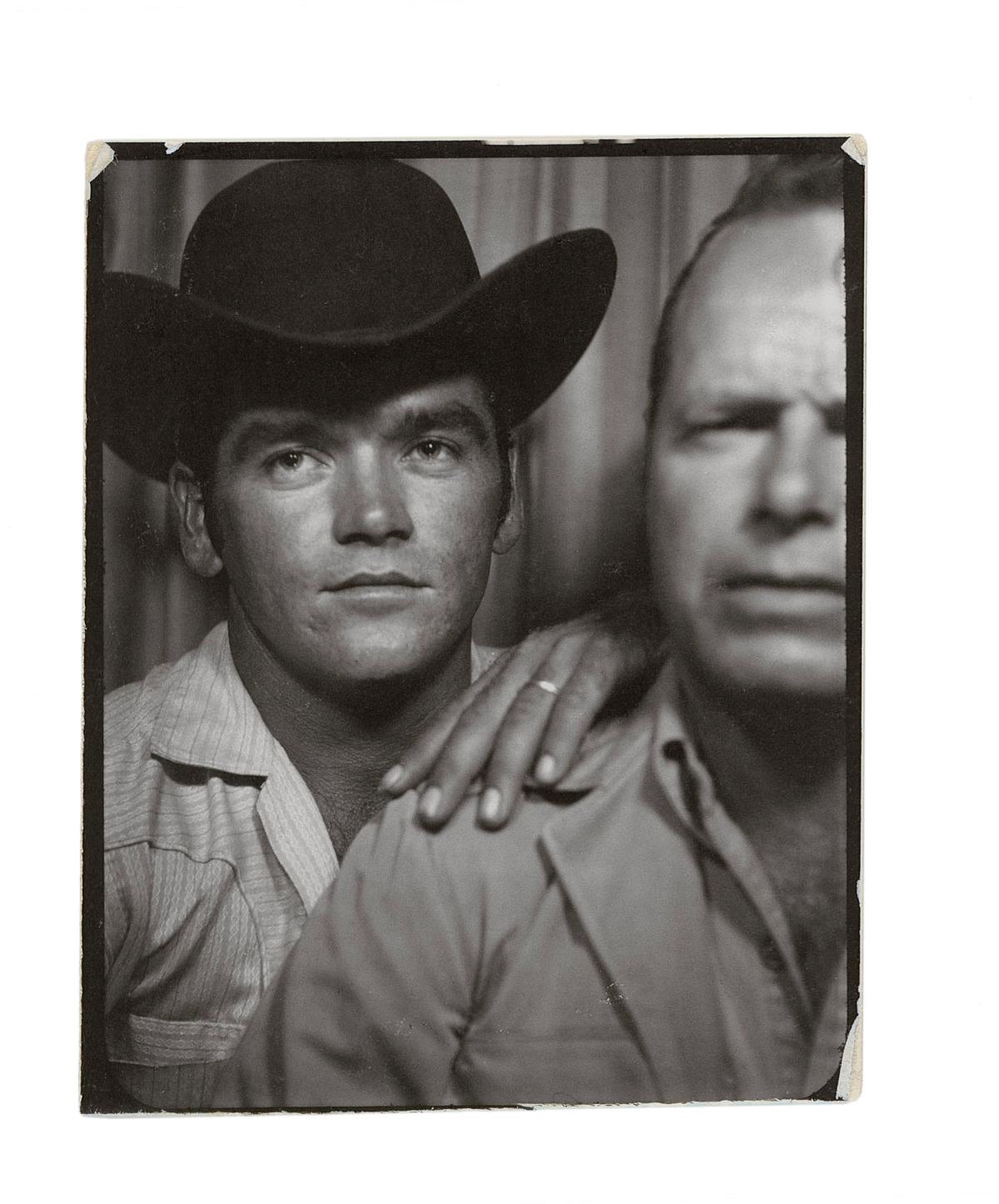

In a sense you could say that I curated the photos in the moment of dumpster diving them. I'm drawn more to black and white; I have an eye more for sort of photo documentary imagery, not so much staged photos. So, no doubt looking back I made some choices as I went along, in terms of not bringing all tens of thousands of them home but just a few thousand. Gavin Morrison and Fraser Stables, the people with whom I worked on the book, were really in curatorial charge. So, we worked together and collaborated, but really I wanted their eye, as visual artists and especially as curators, brought to this. We agreed not to specify a criterion, not to try to pick the best or worst photos, the most beautiful or the ugliest, but to let our eye linger on the photos. And to pick photos that had some depth of meaning to them or were striking in terms of their composition, or their colour field, or the poignancy of the subject matter – without making those into a bunch of rigid categories. It seemed appropriate to photos that were found in a discarded, dishevelled state that we not over-organise them nor overly specify what we found attractive.

In a sense when you look through the book, it's a set of mysteries, sometimes positioned as diptychs and triptychs. It is really up to the viewer to figure out the connection. We aimed to leave some ambiguity and uncertainty, which is I think appropriate to the photos.

Why intercept these photographs when their owners have clearly destined them for destruction? Is there an ethical issue in ‘rescuing’ photographs that have been thrown away?

That's the one I've wrestled with the most. Whatever ethical issues are involved in illegally scavenging don't bother me – not in the least, I take pride in regular law-breaking! But beyond the issue of the illegality of scavenging, there's very much the issue of how we encounter these photos and what respect or empathy we owe them. Once they're dug out the trash, as you say, they really weren’t meant to be seen again, so by resurrecting them or scavenging them out of the trash it does raise the issue of voyeurism. Even if we bring the right sort of attitude toward it, we're still in a sense enjoying other people's images, both in the sense of images of other people and the images that other people produced. So, I think for me, my personal tendency might be to be cynical, or to maybe bring some humour to what I find – but over the years, I've actually become, I suppose, more tender about these photos, more respectful of the circumstances in which they were shot.

The other thing that I find most interesting about that issue is back to the sort of postmodern concept of ‘death of the author’ – that we don't have to read a passage as it was meant to be when it was written. We can read it in whatever context we want.

I think that's true of the photos, and yet I would say, given the circumstances of how they were rediscovered and salvaged, I feel a certain need to at least make an attempt to be respectful of the original intent of those photographs and those doing the photography.

I suppose ethnographically it seems a sort of moral duty to try to be respectful of what was never meant to be seen again in the first place.

Are these photographs in any sense, ‘street art’?

As someone who's written about and participated with street art and graffiti for decades now, one thing I found interesting about this project was that it forced me to rethink what street art means. To reconsider what I had assumed without really thinking about it. Art in the museum or the household is confined to those who have access to it, but street art is there for everyone to see, I assumed. And then I realised, well, this is street art. These are photos that were entirely salvaged from alleys and streets. These are not domestic. They're not in a museum or gallery. They're street photos, but they weren’t there for everyone to see. They were only there for dumpster divers and trash pickers and homeless people to see. It makes me really rethink what else is street art in the sense that it's the art of the open public space of the street, and yet not necessarily paint on a wall, or highly visible. I want to think about that. Could this be thought of as street art, and if so what other kinds of hidden street art might there be?

You are, amongst many other things, an accomplished social scientist. Have your skills as an ethnographer informed your approach to these photographs?

Yes, I would say one way in particular. When I have taught ethnography all these many years and tried to practice it, I always have taught students that the first move is the phenomenological move – that is, the notion that you take the thing itself for what it is on its own terms. You don't bring to it an investigative framework, you try to understand the phenomenon with which you're dealing and let it in a sense teach you how to study it. And so at first some 20 years ago I began to create folders – you know, like urban photos, family photos, dog and cat photos – and then I thought to myself, that's really not appropriate to the subject matter, because these are lost, discarded, jumbled photos that were haphazardly discovered by me.

It seemed to me that I needed to preserve some of that haphazard nature.

And to leave that in place as I thought about how to present them, how to save them, even how to store them. So, I've abandoned my early attempts at categorisation. And now I think of them more holistically in terms of, again, the mix of intentional and unintentional image, person, photographic technique. It's a photographic history. I let all that swirl together as I think about which photos matter and how they matter to me.

Are you materially responsible for this corpus? Do you feel a responsibility to these resurrected images? And to share them in material form?

First of all, these photos are often materially deteriorated themselves; they've been out in the world for decades, and in some cases for centuries, so many of them are quite delicate. The writing on the back is faded. They have coffee stains. They are dog eared. In that sense they almost feel like injured animals, I guess. Once I save them, I feel a need to take care of them and not impose further damage on them. But of course, then I end up with the same issue that no doubt the original owners had, which was what to do with all these photos? So, it's interesting that as this work has become more public, I've gotten message after message from people asking my advice on what to do with all their old photos, and I tell them, you're asking the guy with the closet full of old photos! There really is no good answer as to what to do with them. They do tend to accumulate and then upon being thrown away, tend to be experienced as a kind of tragedy or certainly as having a great amount of pathos. So, I'm still troubled.

As you know, I've let a few out into this latest book and we had a few urban shots in an earlier issue of Nuart Journal. I've also had some public presentations, but I suppose I'm being careful about not letting them become part of the algorithmic web of photos out there – not digitised, not available to anyone. I suppose I do feel a kind of tender proprietorship toward them at this point that's dangerous, curious, and problematic.

In the book you describe the photographs in certain places as ‘ghosts’. Can you tell us some more about what you have called elsewhere, ‘ghost methods’?

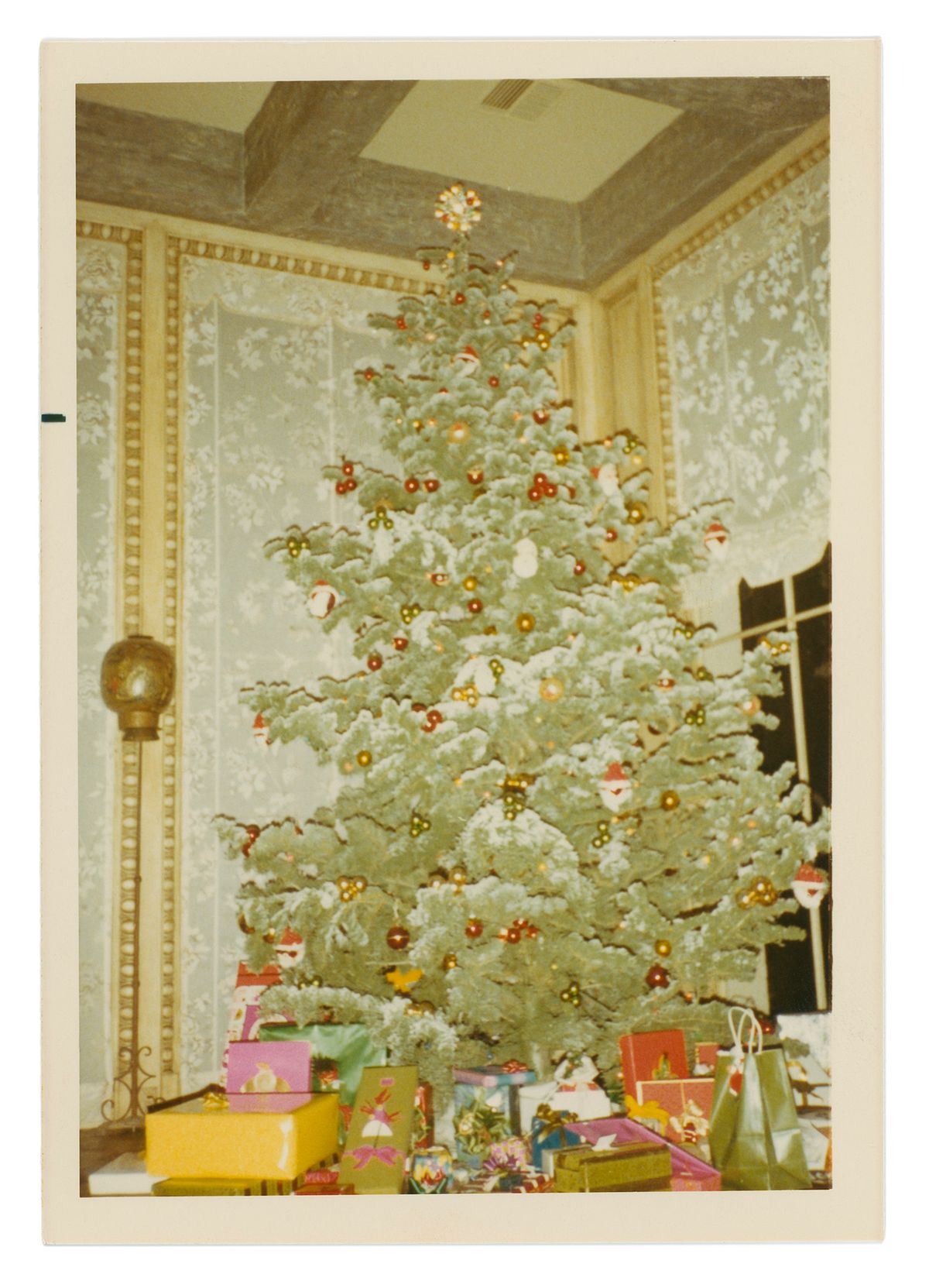

In an earlier book, I began to rethink my decades as a researcher and my training as an ethnographer. Once, I thought to look for only what's there to notice, what's present, but it began to strike me increasingly that with fugitive populations, and refugees, and precarious work, and people on the move, we need to think about how to study the ghost of what happened, not just what is happening in the moment. So, residues and traces and ruins and at least for me, training myself to notice what's absent as well as to notice what's present. In that sense, decades-old discarded photos already fit that research methodology, but bringing that mindset to them I found especially helpful because I realised that I needed to be careful not to assume that what was present in the photos mattered more than what was absent. For example, the photos tend to be records of special events. As the great songwriter John Prine said, we tend to create images of the good times in between the bad times, and so these photos are not a thoroughgoing chronicle of everyday life. They're more of an episodic chronicle of happy moments and new automobiles and 10 year old birthdays; in that sense they leave out as much as they capture. They certainly show the absence of ethnic diversity, and in the largely white neighbourhoods where I found them, they become documents of who is not allowed to be in that neighbourhood at that time, or at that birthday party. They are certainly documents of rigid binary gender roles, of not allowing people to transgress those boundaries, and you see almost absurd displays of femininity and masculinity in these old photos. So, it strikes me that again once we think about ghost methods and reorienting ourselves to a world where absence may be as evocative and informative as presence, then we can use that. We can interrogate old photos or old archival residues for what they don't tell us as much as for what they do tell us.

I realised also that these photos were ghostly in the sense that they were residues of a particular period in photographic technology. You know, these photographs entail not only the image, but the period in which that image was sent to a developer and then fetched a week or two later having been printed on a piece of photographic paper. These photos all exist somewhere between the tin type and the digital camera. They are really markers of and ghosts of a particular period, and what I especially love is the photos where you can actually see the shadow of the technology. As most of us were taught in our first photography class, you put the sun at your back as a photographer and therefore the sun is on the face of your subjects and illuminates their face, then you take the photo. But what that means often is that if you're not careful, your own shadow is in the photo, so in many of these photos you can see the ghostly presence of the shadow of the photographer's body, and you can also tell what sort of camera they're using. In some of the older photos, you can see their elbows splayed out to their sides and their heads dipped down as they look down through a viewfinder in an old camera. And in photographs from later on, you can see their arms much more up beside their head, and they are looking straight ahead as they look through a viewfinder that's at eye level. So, if you again question these photos, you can actually see the use of photographic technology in the shadows of those taking the photos. And that's very spooky and eerie and haunted in a really beautiful way.

Actually – and I really shouldn’t take credit for this because a colleague of mine pointed this out – today, we look down into the screen on our digital camera or phone. We can immediately see the photo we took and delete it or try again if it's not right. But these photographs date to the time in which there was no such vision of the photo in real time, and the film had to be taken from the camera and carefully kept out of the sun, sent away or taken to the drugstore, or the pharmacist and gotten back. What that also means is that these photos are more likely to be accidental and surreal. You know, to have a photo that no one knew was in the camera, the dog walking out of the frame as they try to photograph the dog, or the kid exiting the frame on their bicycle. I think this period of photographic materiality and technology also allowed for and almost ensured the kind of beautiful mistakes and engaging errors that are probably lost now. Largely because we can now edit in real time the digital photos we're taking.

I guess with analogue you had a limited number of shots and the camera counted them down. Towards the end of the roll, my Dad really used to agonise over which shot it was going to be for at least 10 minutes before he’d actually press the button.

That's a lovely point. The end of the roll, as noted by the counter on your camera, became more fraught with the need to get it right because now we're out of film! What a concept to be out of film in today's world. Shooting with a film camera also had a warmth to it that you can't find in the digital. I think it's the visual equivalent of a phonographic record versus a compressed audio file in that sensuality, materiality comes through in the sound or in the image.

And the whole idea that chemicals have to interact with light?

Yes, that's another thing. In these photos you can see the deterioration of the photographic process and the photographic paper differently. There are some photographs that look like about the '60s and '70s, at least in the United States, that turn a God awful shade of pumpkin, orange yellow, as the print deteriorates, while others retain their black and white beauty. So yeah, I mean if you knew enough about film technology and development technology, you could probably tell what the process was that led to that kind of deterioration. I mean it's linked to what film stock it is, and what company, and where you get it processed.

You must have a million other projects to be working on, but do you have any kind of plans for working further with this collection?

Well, I have far fewer projects than I once did because I'm very happily (mostly) retired now. But many of my favourite photos out of these many thousands did not make it into this book for various reasons, and so in that sense, and depending on how this goes, it would certainly be a pleasure to put together another edition of this book, maybe thematically. All of that could violate what I said earlier, maybe not – maybe it will be just the next 100 most interesting photos. To my mind, there's much yet to be seen and talked about and learned from with this accidental street archive of old photos that I seem to have developed, so I look forward to playing with it gently and letting it suggest to me what to do next.

This seems such a gentle way into such an otherwise overwhelming corpus. I mean, if you had to collect and sort these photographs for a funded research project you would be working mechanically through them with some kind of fixed goal and deadline – it's really lovely that you can make the time to organically let it speak to you.

Very well said. That also makes me think of something I hadn't thought of. Ethnography – which of course is my great passion – is all about losing yourself in the subject matter, getting rid of your notions of time and place and learning from the situations you're in and taking your time. Since these photographs are the result of that kind of practice, it seems to me they need to be treated that way now that they're part of my life too. So, I'm not really in a hurry, I'm not trying to impose a grant driven deadline or a 12 point framework. I just keep looking at them to see what emerges next.

A selection of photographs featured in the book Last Picture by Jeff Ferrell.

Jeff Ferrell is Emeritus Professor of Sociology at Texas Christian University, USA. He is author of the books Crimes of Style, Tearing Down the Streets, Empire of Scrounge, and Drift: Illicit Mobility and Uncertain Knowledge. He is also the author, with Keith Hayward and Jock Young, of the first and second editions of Cultural Criminology: An Invitation, winner of the 2009 Distinguished Book Award from the American Society of Criminology's Division of International Criminology. Ferrell is founding and current editor of the New York University Press book series Alternative Criminology, and one of the founding editors of Crime, Media, Culture: An International Journal, winner of the ALPSP 2006 Charlesworth Award for Best New Journal.