This is an edited transcript of a talk originally given at SAUC, Lisbon, July 2021. A version of this talk was also delivered at Nuart Aberdeen, June 2022.

This is an account of the curatorial ideas behind Flash Forward, a large programme of art and music presented in the laneways of Melbourne, Australia. In 2021–22, the Flash Forward project commissioned 40 artists to make 40 laneway artworks and 40 bands to make 40 albums that were released on vinyl, as part of an effort to support creatives and revitalise the city over the course of six extended lockdowns due to Covid-19. In curating the programme, the social and architectural history of Melbourne and its grid of streets and laneways was taken as a context from which to jump forward into imagined futures for the city.

Lachlan MacDowall:

Here in Melbourne, for much of the pandemic, we have been in a giant prison. We have had an unusual journey with Covid in that through 2020 and 2021 we had very few cases of community transmission and we've had a strategy of elimination which has resulted in six lengthy lockdowns, including one lasting more than three months where the population stayed indoors in our homes. This has had a dramatic effect on the city.

When this took place, I had been doing some work with the City of Melbourne and a variety of things happened all at once that enabled me to propose a large intervention in the city, with multi-million-dollar funding from the local and State governments. This level of funding came available because due to the lockdowns there really was a high level of concern about Melbourne becoming an empty city and a city full of unemployed people, particularly creatives.

So, in order to try to grapple with the effects of Covid, and to employ artists and bring people back to the centre of the city we proposed a project to activate the city's laneways. Melbourne is well known for its street art and graffiti cultures and the city itself has many laneways. This is the main aspect of Melbourne's branding. So, I was given this opportunity to curate a project around laneways and street art.

Now when other people in Melbourne talk about laneways and street art, they have perhaps slightly different ideas than myself. As in many places, street art has become very commercial, very mainstream. And the laneways have become a branding element of the city. So, my attempt was to create a much more critical idea for this project. Here I'm thinking about the ideas of Javier Abarca and also the work on some of the more critical aspects of street art that we've seen at SAUC in Lisbon and from Nuart's Festival and Journal. These were all very influential in proposing this project, Flash Forward.

So, there are around 200 laneways in the centre of Melbourne: we chose 40 laneways and commissioned 40 artworks. We also commissioned 40 bands, and each of the band made a new album of music. So, we had 40 artists, 40 laneways, 40 bands. We then released all of the albums on vinyl, and we had a range of other activities, so there were about 150 people working on the project and about 450 artists working on the project.

In order for this to happen, it needed some clear curatorial ideas, so here I just want to share a couple of the curatorial ideas that were behind the project. These ideas come out of the conditions as I said of our city in lockdown, a lot of people working from home, a lot of economic disruption, especially for the creative economy, and some very negative government interventions at a national level, but a very active state government who was willing to spend an unprecedented amount of money on street art and other things.

There are three curatorial moments or ideas that I want to mention that motivated the project are Melbourne as a Grid City (1837+); the death of Walter Benjamin's (1941); and the Times Square Show (1981).

Melbourne as a Grid City

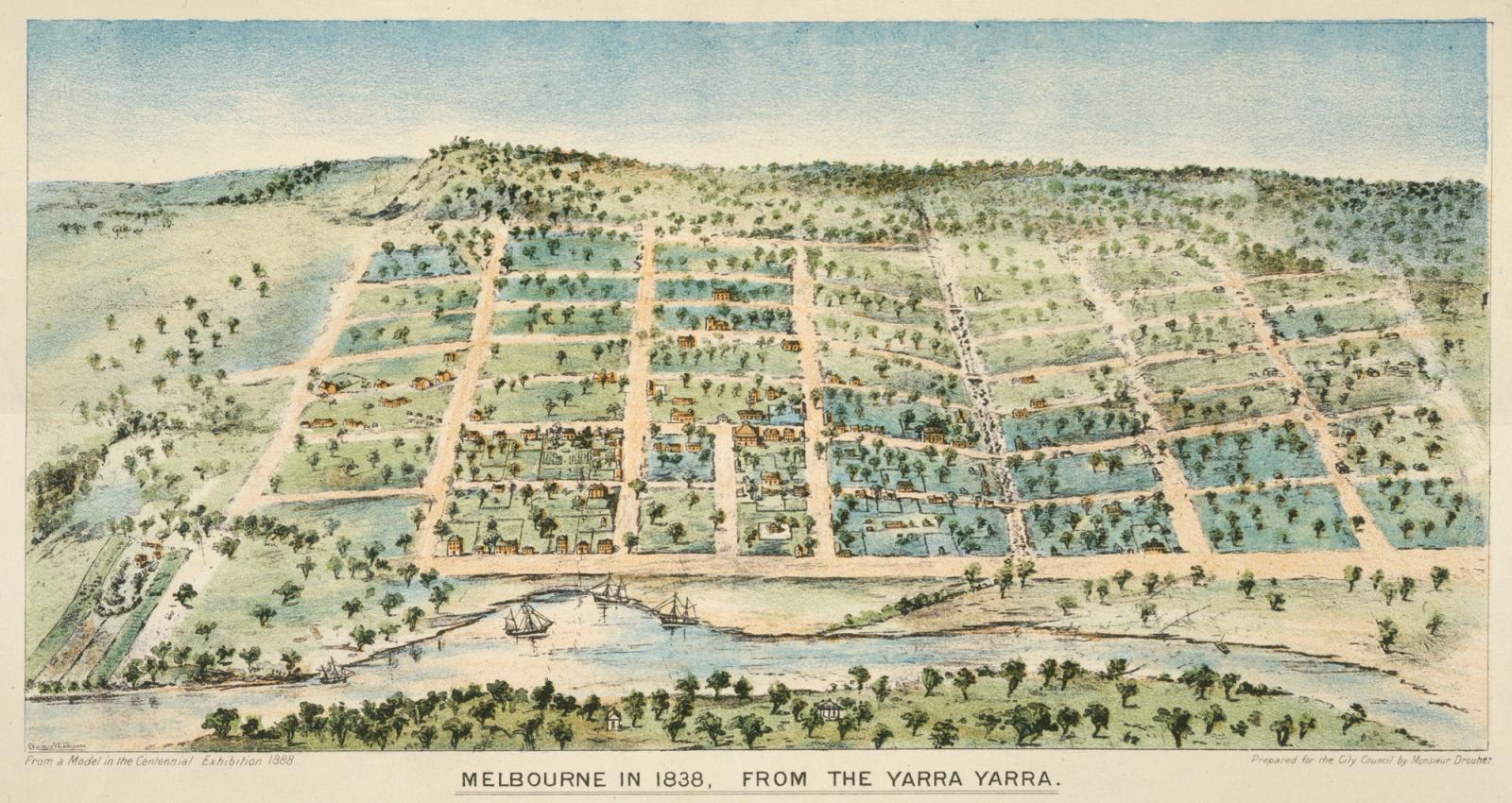

Melbourne is a city based on the imposition of a grid in colonial time and it's out of this grid that we have these smaller streets on the laneways. The city is built on a completely different country that existed before European settlement. This is a map of the language groups of the indigenous tribes around Melbourne (known as Naarm) that continue to be the custodians of this land.

The occupation here by indigenous people dates back to at least 40,000 years, and there's been a recent, slightly mysterious, contested archaeological dating of a fire pit down the coast from Melbourne that dates back around 200,000 years. So, this is a very ancient place and the colonisation and the destruction from European settlement is very recent. This is something that's very much in the minds of Australians at the moment as we grapple with the impacts of colonisation and try to rethink the notion of the city as being both a European construct but existing on indigenous land, so the inclusion of indigenous and First Nations artists and their perspectives in the project has been a really important element.

But from the early 19th century, land speculators arrive in this territory. While they are mostly Australian born, the territories are under the control of the British government and in the late 1830s we see the beginnings of Melbourne, the site of a swampland and a billabong (waterhole) on a river, is laid down with a grid system.

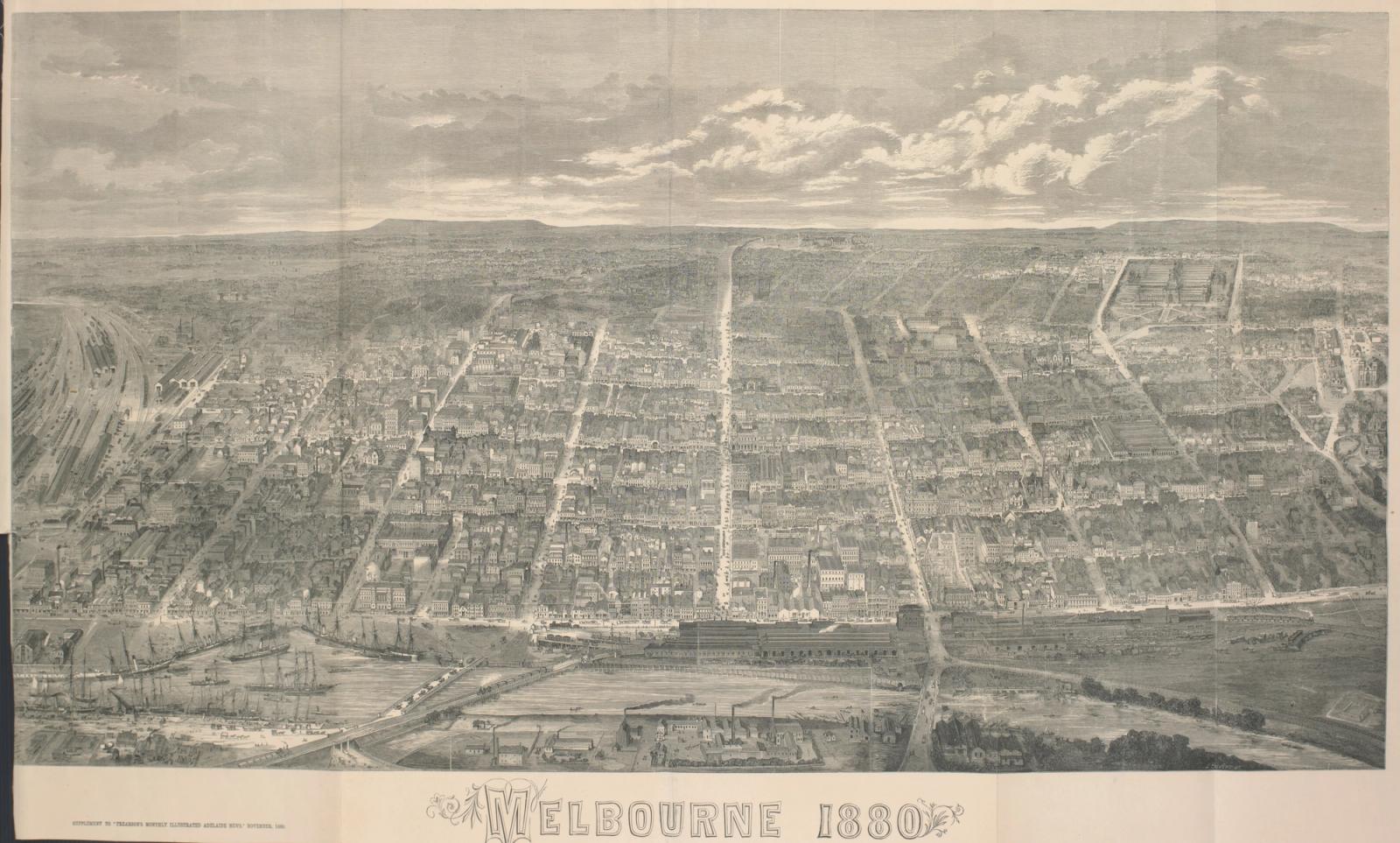

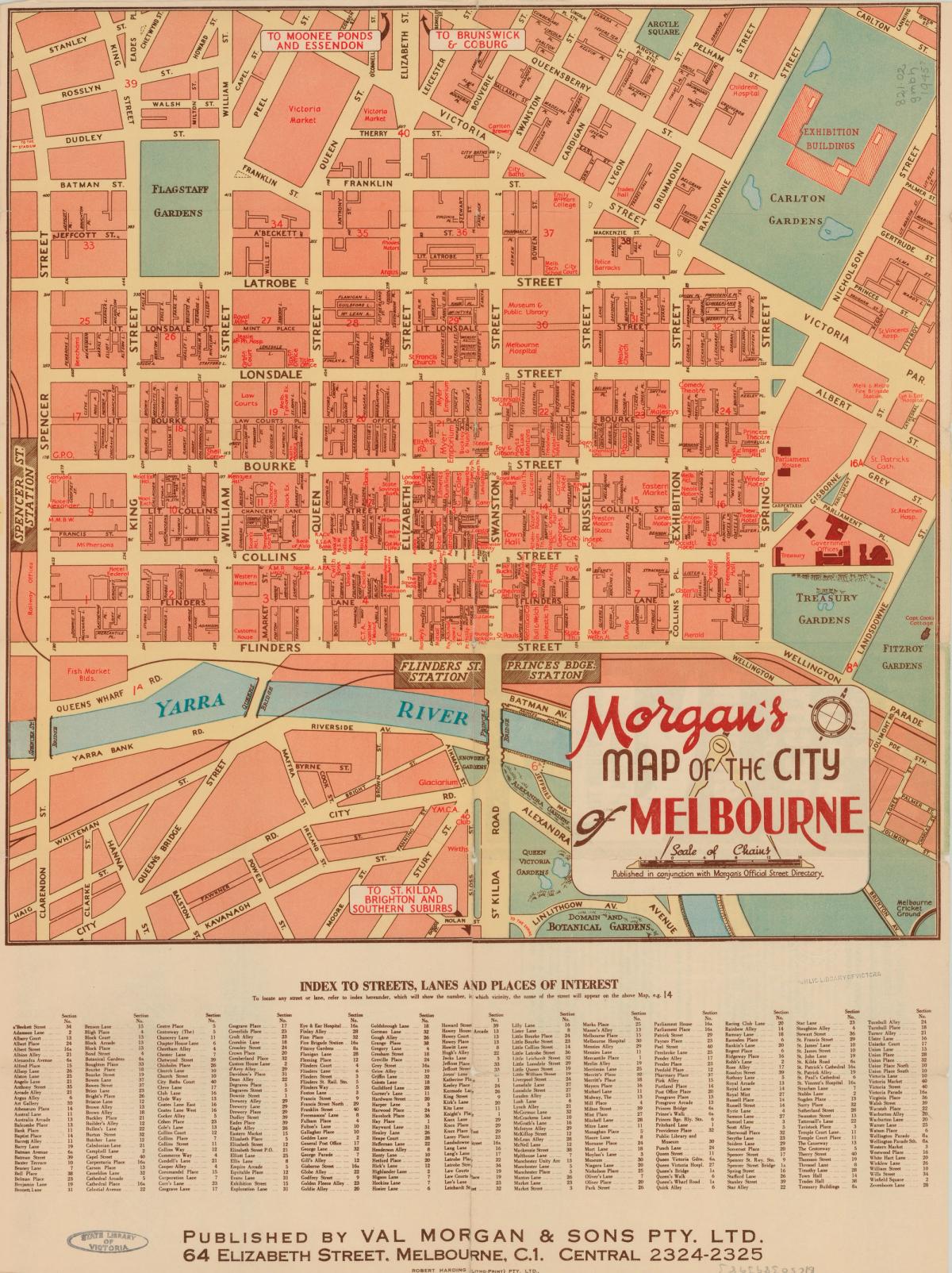

Below is the famous grid of the city. It's the same grid that is in Manhattan. It's the same grid that's in many European cities, and you can see these major lines here represent the major streets of Melbourne. The grid is often talked about with civic pride, for example that there are wide streets that are easy to navigate. But you can see also in this grid, apart from the main colonial streets, a series of much more informal, messy laneways. So, the first move, from a curatorial point of view was to create a little bit of space between the colonial grid and the smaller, more informal and oddly shaped laneways of the city. Because these laneways, as in other cities, are really about what's repressed in our culture – the service laneways for the delivery of commodities that are then sold out at the front of the shop. They are a service entrance for labourers where labour is repressed, and also for the repression of bodily activity, bodily waste, toilets, sex – all the kind of things in culture that are repressed are connected to the laneways.

The British surveyor Robert Hoddle laid down the grid in 1837, and as I thought more about this colonial history, I was also struck by an odd historical coincidence, that Robert Hoddle himself was born in London in the 1790s, around the same time as Charles Babbage, and in the year that Hoddle lays down the grid is also the same year that Babbage and Ada Lovelace developed the first computing system, the Analytical Engine. So, there's this historical moment in the 19th century in Melbourne that sees the colonial logic of the grid matched by the kind of technocratic logic of early digital culture. I wanted to think about these laneways and their history and about how they are still reminiscent of this grid of colonial logic, and also the beginnings of digital logic and the digital city that's now become pervasive, particularly after Covid.

The logo of the project began with a black square and the black square has within it a number of small laneways that don't go anywhere, little culs-de-sac. The object of the project is to slice into the black square and carve off these small spaces. We are encouraging people to try and travel through the city in a different kind of way.

The architect Le Corbusier says something like anyone who travels along a straight line in the city knows exactly where they want to go, but we are encouraging people to move through the city in a way that is not just about shopping or not just about traveling at the highest possible speed, but in taking these little détournements down the laneways and having a different kind of experience of the city that isn't structured by commodity relations or structured by a sense of private ownership of the city.

Interviewed by Mahmood Fazal, the Melbourne rapper Tornts, describes the long-term effect that living in a grid city can have:

The Sydney sound was more trappy. Melbourne had the darker, harder and grittier sound,” explains Tornts. “We wore black TNs and big jackets 'cause it was colder. A lot of work went into writing and trying to put words together in different ways. And it reflects the way the city looks, the way the city is put together. It's like a grid. There's nowhere to hide.

Tornts talks about rap music in Sydney and claims that Melbourne has a particular sound that's built around the way that the city is organised around the grid, finishing with this statement, ‘It's like a grid’ and ‘there's nowhere to hide.’ Here, rather than the grid being a positive civic feature, it is seen also as a trap with a very rational, confining kind of logic. So, the grid was an important kind of feature to rethink the laneways against this colonial corporate logic.

Walter Benjamin's Arcades project

I was also really moved to think about the connection between laneways and arcades and the amazing work of Walter Benjamin in his Arcades project. This is often thought about as one of the most significant philosophical works of the 20th century. This is a study of the arcades in Paris in the 1870s, and arcades are kind of like covered laneways. But where it becomes most interesting in Benjamin's work is the attention to detail and the kind of historical delirium that's made possible by his very unusual methodology of carving up the small details of everyday life in the laneways and thinking about the city in a different kind of way.

We do have an example of a Parisian style arcade here in Melbourne, so there's a kind of touchstone for the project. Benjamin himself died tragically, committing suicide in 1941 to escape the Nazis, while carrying the manuscript of the Arcades project. But the Arcade project lives on. I think Benjamin's death in fleeing the Nazis is also connected to the possibilities of these concrete laneways having a kind of anti-fascist impulse. Benjamin's work is anti-fascist in that it's explicitly political about the making of art, but it's also anti-fascist in that it is not spectacular. It's very much about looking under the skin of the city, looking into the small details of the streets and the cities, so Benjamin's methodology in looking at very small details has been crucial in this project, where we have often looked at very small details in the laneways in order to connect artists and musicians to certain spaces. Benjamin's ideas are a very idiosyncratic mix of Marxism and mysticism, but I think the Arcades project gives us the capacity to think about some things that are usually repressed in ordinary history. For example, Benjamin has a section in the Arcades project on prostitution, sections about different types of commodities, and sections about street signage and the alphabet, some of which really resonate with graffiti and street art.

Due to the unusual circumstances of Covid, in this project we had a large number of staff and a large budget but mostly our artists are used to working on very modest scale, and I myself am not so interested in monumental corporate street art. So, we are trying to use a huge budget to do very modest things. Benjamin helps to keep us grounded in the little things and the little details, and stops us becoming monumental, majestic, and overblown, in staying material in our thinking and looking for coincidences and very small gestures. You know, when I go into these laneways like a graffiti writer or a street artist, I'm looking at the walls, thinking, ‘yeah, that's a good wall. I'm gonna take that wall. I'm gonna tag here. I'm gonna climb there’. So, I'm trying to curate a project that is not in the vein of many global street art projects which tend to feature large figurative corporate murals. Walls that are not so interesting.

So, this becomes another kind of key touchstone. We have laneways as being anti colonial, laneways as being anti corporate, and laneways as offering real material for an anti-fascist project, all of which are very relevant for our contemporary life.

The Times Square Show

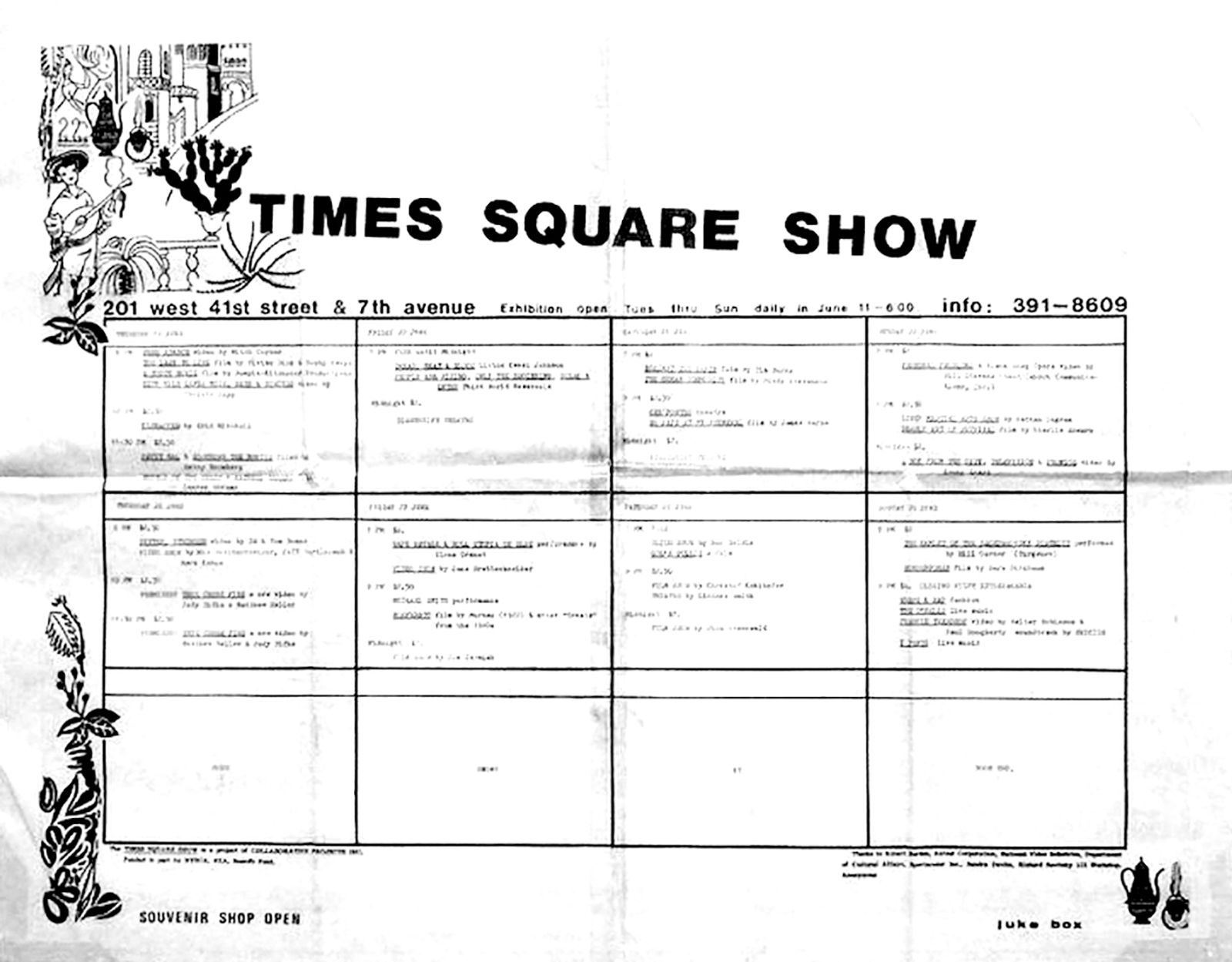

Finally, I want to mention the third curatorial touchstone, which resonates with people in Melbourne. There's another city that's undergone major depression, that's been full of empty shops, that was also about to experience a pandemic. This is the context of New York City in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a period when the city is nearly bankrupt, a period just before HIV/AIDS erupts into the communities there. And this kind of decaying city is also the context, as we know mythologically, for an amazing burst of creativity. Right at this moment when graffiti writers and street artists, when gay artists and straight artists, black and white and Puerto Rican artists exist in this kind of melting pot of work, which is emblematised by the example of the Times Square show (1981).

This exhibition was in a massage parlor in Times Square that was taken over by a group of artists for a show organised by the Collaborative Projects group, along with Fashion Moda. Basquiat and Haring exhibited their first works here. So, this event and this context is at the heart of the thinking about the project. Is there a psychic memory that exists for Melburnians of an empty and derelict kind of inner city? This certainly was the case in the 1950s, as depicted in a famous Melbourne painting of people leaving the city to go home to the suburbs at 5 o'clock. But I think that psychic memory of an empty inner city is also a psychic and unsettled memory of the grid and the land speculation that gave birth to the European city, and of course, the colonial violence that's still kind of repressed.

Laneways offer an opportunity to set aside the pervasive logic of the city as a place defined by rational actions, property relations and commodity exchange, by the cross-hairs of capitalism and colonial logic. This is the broad curatorial premise of rethinking these kind of laneway spaces and thinking about how we can use this idea of getting off the grid as an opportunity here to use and to commission artists, art and music, street art, and other things to rethink the place of the city.

Lachlan MacDowall is a writer, photographer, and curator based in Melbourne. He is the author of Instafame: Graffiti and Street Art in the Instagram Era (2019) and, with Kylie Budge, Art after Instagram: Art Spaces, Audience, Aesthetics (2022). He is currently Director of the MIECAT Institute and with Miles Brown curates Flash Forward, a programme of art and music commissions (flash-fwd.com).