This paper is a meditation on the importance of artistic labour and the processes of creating over the final artistic ‘product’ in the work of artist Oleg Kuznetsov (Moscow, 1993; referred to here on out as ‘OK’, as per his tag). In recent years, OK has expanded from graffiti across different media and canvases including printing charcoal on snow, painting air, non-additive collaging, sketching, and private and public interventions from his own body to entire buildings, although his work is very much underpinned by many of the principles hailing from his street art origins. Such notions of artistic freedom, ownership (or lack thereof), ephemerality, art as invisible labour, and the intimacy between artist and creation as being central to its value, all provide and constitute some of the poetics of the space between the moment of each work's conceptualisation and completion that will be explored here. In keeping with OK's practice and the importance he places on incidental aesthetics and happenings that enrich his processes, the thread of this article weaves through his varied experiences and motivations during these moments and spaces in time, thought and making, as opposed to being an article as ‘final product’ that draws various lines of argument to a singular conclusion.

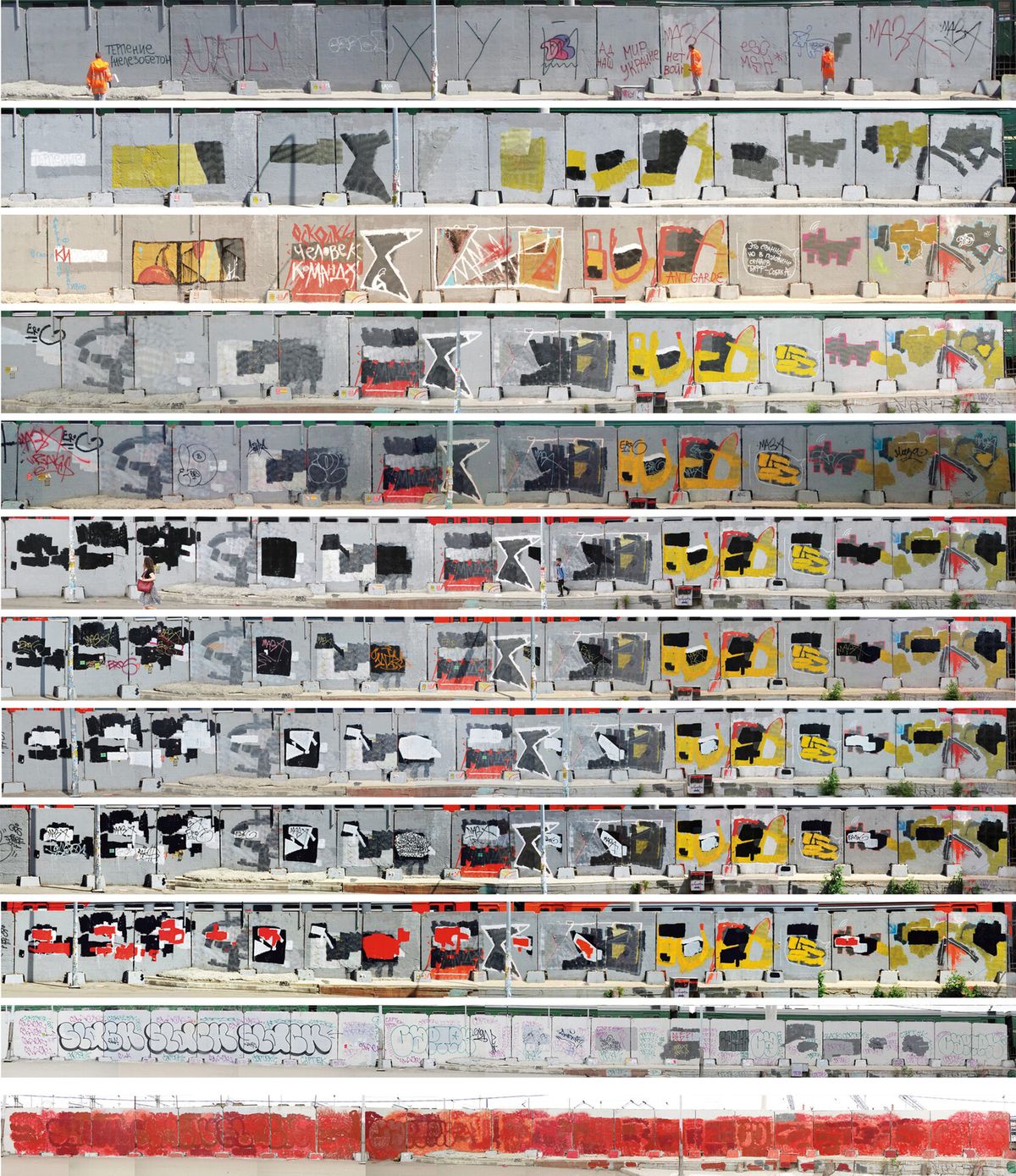

An illuminating portal into OK's practice is a hitherto unknown anecdote from what is perhaps his most known project to date, ‘Kurskaya Wall’, because it synthesises so much of his modus operandi. While hiding in plain sight under the guise of being a council worker buffing over graffiti on a wall at Moscow Kursky railway station in May 2015 (Figure 1), OK was approached by an onlooker suspicious at his use of bright, unmatched colours for the task, rather than the staid greys and beiges of usual council fare. Believing he had indeed caught out an artist at work, the man asked OK if he would paint over his initials if he added them to the wall, and to his surprise, OK kept his cover – at once street art, performance, and appropriated labour – and did just that. However, this led him to feel that for removing the physical manifestation of this man's energy, he owed it to him to revive it elsewhere. This occasion came when OK moved to his residency at St. Petersburg's Street Art Museum, where he reproduced the man's tag in the space's ‘hall of fame’, proclaiming it was that of a famous yet mysterious Moscow artist.

It is important to note that the stress here is on the energy, the process, the in between rather than on the tag itself, that being a final product. It is the significance of the former over the latter that underpins so much of OK's philosophy and intentions. Likewise, there is the ‘why’ of the Kurskaya Wall project, which he sums up rather as a ‘why not?’: nowadays it isn’t something out of the ordinary to see people painting in the streets, so the power of illegality – and often protest – that graffiti once had, has been largely diluted. On the other hand, especially in Moscow where graffiti is usually painted over by the council within a day, indeed why not subvert this power structure, and appropriate the cover-up process into an artistic action in itself? The project became a layered, constantly evolving process, with unagreed collaborations from painters who worked over OK's buffs, that he would then buff again, in different colours and to fit over the new shapes. All that is left now are photographs documenting the wall's changing surface throughout the process, but neither the photographs nor the wall are the artwork. Instead, the artwork is lost, because it was the actions and the energy. Quite the opposite to a gallery show that a visitor came to, it was a show that came to the ‘visitor’: the passer-by in the street, who would not have intended to find art intervening in their journey at that particular location.

It is often through photography that a great deal of OK's graffiti work – or another process in action – is captured. There has been growing conversation in the art and heritage community in recent years around the ethics, needs, and possibilities for the physical conservation of street art (MacDowall, 2006; Merrill, 2014; Hansen, 2018), but in all cases – particularly in contested spaces – the photograph is of course the most widespread tool when it comes to preservation (Blanché, 2018). However, it is worth mentioning that although OK takes photographs of his graffiti, he doesn’t see himself as a photographer, nor the photographs as a product. Instead, it is just another process to form ‘a document of the appearance of something, a reconstruction of an environment now deconstructed’ (OK interview, 2022).

A series of analogue photographs of bare walls constitutes ‘Graffiti Pieces I Never Did’ (2021). These are essentially images of absence, records of something as transcendental as thought and intention rather than the visual (Figure 2). OK imbues in them a sense of being an in between space, at once evoking melancholy, while waiting for something that will not come – or even if it does, that will likely be removed immediately, as per a Moscow law that owners will be fined if they do not remove graffiti from their buildings (Bacchi, 2019). Of course, the concept is very much about the inspiration to do something and the opportunity not taken, a nod to the common thought among street artists before a large, blank wall that ‘this would be such a cool place to paint’, but often never getting around to it. By documenting these spaces, OK converts this sentiment into something intentional, describing it almost as ‘striving to fail’ (OK interview, 2022), whereby he has noted the blank building, but chooses instead to immortalise it in this peak state of imminency, leaving the action unfulfilled.

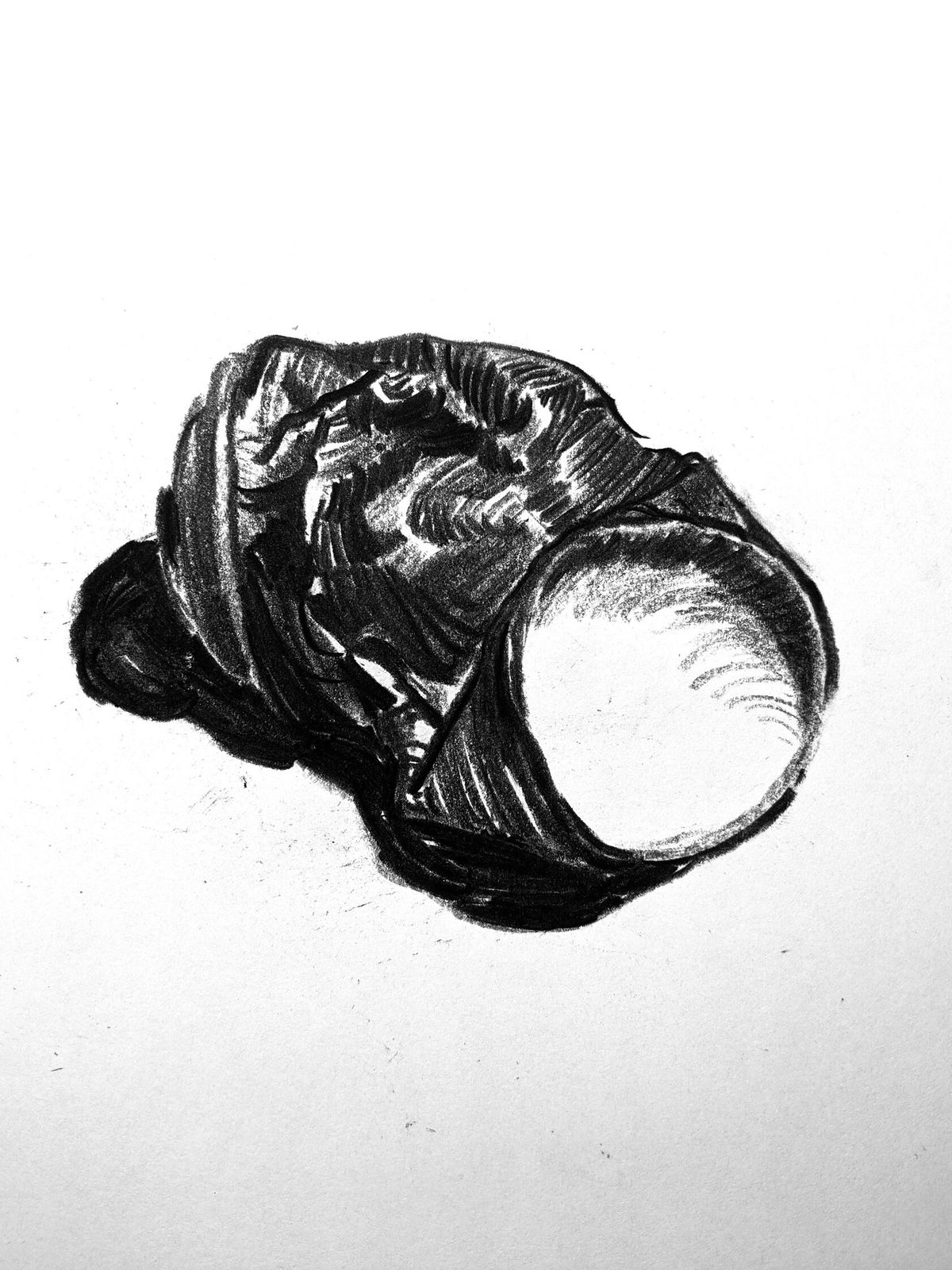

The series ‘1/36’ (ongoing since 2019), on the other hand, captures an intimate process, with the camera literally between the artist and the wall, yet save for a few images in which we see a spray can, there is again an absence of concrete information and situation (Figure 3). Taken at night, on 36-frame photographic film, these were blind photographs for both OK and the subjects, with no viewfinder, checking or deleting, no flattering angles, posing, or direct looks. Such an intimacy is created that one can only imagine the power each of these moments held, what was going through the mind of each of the artists, what they did immediately before and after. The series succeeds at leaving the viewer more intrigued by these questions than over what the artists' final creation might have been. In ‘Study for Crumpled Spray Can’ (2019–present), however, we move from a powerful absence to a somewhat pathetic presence (Figure 4). These drawings are a personal comment on how the spray can as a medium lost its power for OK, signifying a move into charcoal – which, almost mockingly, is what he used to make them – and what he referred to as ‘breaking the habit [of graffiting]’ (OK interview, 2022). Also of note is the intimacy afforded by the direct contact of charcoal to the paper, as opposed to the space between implement and surface in graffiti, although OK certainly explored and stretched that concept until he found the space in between, whereby charcoal would reach its surface in particles or through an intermediary surface, rather than through direct, drawn contact.

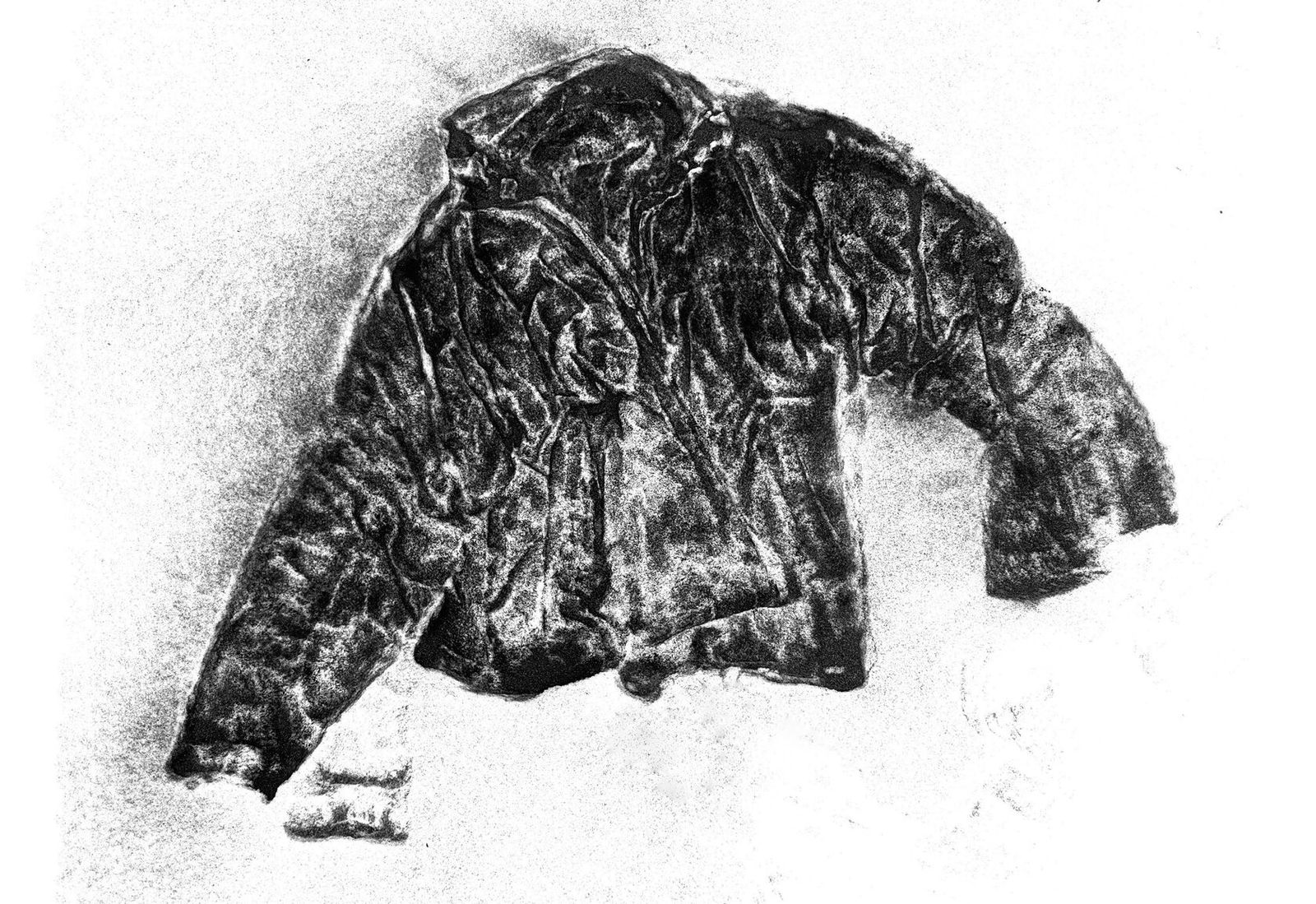

One such example is a part of the immersive installation ‘Who Lives in My Wardrobe?’ (2020). Rare in his portfolio for being an interior-based piece, it consisted of OK's bedroom space behind wardrobes that he had converted into a Narniaesque entrance, and on the bed an imprint of his naked body formed by smearing himself in charcoal dust and laying down on the sheets (Figure 5), the result being reminiscent of David Hammons' body print works. OK then invited people to come and visit the work in his shared flat when the time came to move, allowing visitors into his space between wardrobe and wall for one evening only. Also carrying forth the very Soviet-era concept of apartment exhibitions (albeit without the political reason for a clandestine event), it was even more intimate, with the sensual imprint of his body at its most private and vulnerable. For ‘Snow Prints’ (2019 – present), he laid items including a jacket, a broom, or himself, onto snow to make an imprint, before using sandpaper to grate charcoal onto it, creating something of a reverse X-ray-type image (Figure 6). Unlike a solid wall where there is a chance (however small) that graffiti will survive somehow, nature dictates that a work on snow is destined to disappear every time. This inevitability, along with the fact that the objects themselves are rather mundane, is perhaps one of the most perfect representations of the ‘process-over-product’ mantra of their maker.

A similar sensation, albeit a very different expression, might be ignited by his work ‘The Lawn’ (2020), which consisted of OK painting grass green (Figure 7). While ‘Snow Prints’ would disappear due to nature, ‘The Lawn’ was almost invisible (not quite a perfect shade-match) from the start, with the long-lasting thick paint undoubtedly ultimately defeating the patch of nature acting as its canvas. Certainly a futile activity, it was actually the reperforming of a task that OK had carried out while on military service, when, for lack of more productive ideas, his commander insisted he paint the grass so as to be busy with something in case the army general were to pay a visit. Alongside other seemingly banal tasks such as making the bed perfectly without a crease, OK saw a correlation between this service and what art can also be at times – what it can mean for artists who feel a need to always produce, i.e., art ‘just for its own sake, with no function’ (OK interview, 2022). However, through his performative recontextualisation, OK has also seemingly liberated the task from its own banality, appropriating it in an artistic context. By remoulding an authoritarian order devised within the framework of discipline and service, into an act of free will and subversion with a touch of ridicule, he has taken back the power in somewhat similar fashion to when he took on the role of the council worker in ‘Kurskaya Wall’.

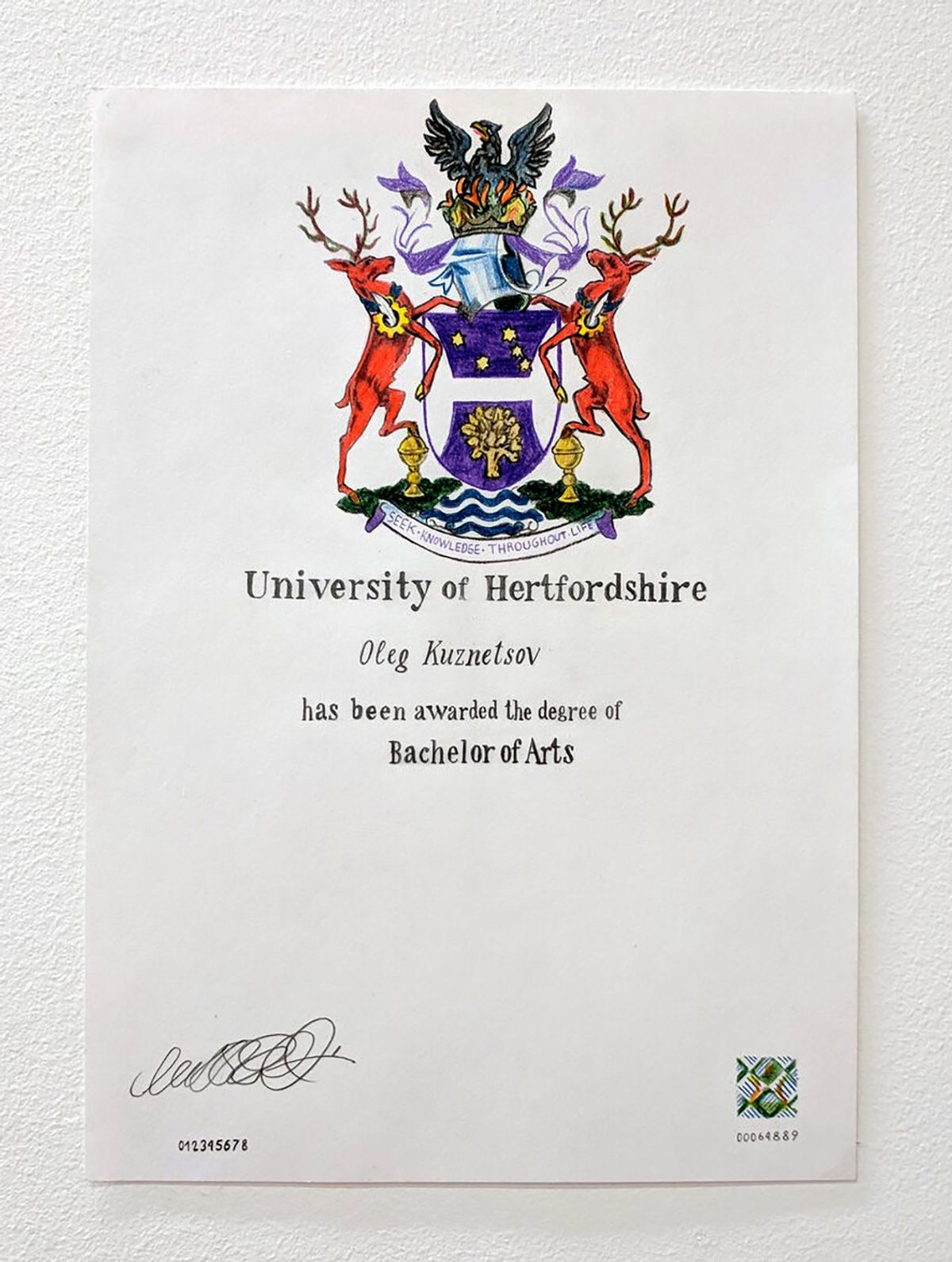

In short, through art, OK has made meaning out of an enforced ‘duty’ that for him had no significance, out of the ownership of his time, and even out of putting into practice his ideas about simply making art without meaning (as paradoxical as it may seem here). It was Joseph Kosuth who affirmed that ‘art is making meaning’, and one can also perceive a sense of his great ‘One and Three Chairs’ here, with OK's original task, his reenactment, and its documentation on his website taking the seats of Kosuth's real chair, image, and descriptor. OK in fact directly references this in his ‘Sketch to the Work #1’ (2018), a coloured pencil drawing of his degree certificate from the British Higher School of Art & Design (Figure 8). He exhibited it in his graduation show, describing how alongside the original, the image – albeit not a perfect digital copy – also constitutes a description of itself, leading him to conclude, ‘I have one and three diplomas’ (OK interview, 2022). The final product of the degree, symbolised by the certificate, and even the art show, did not matter to him in the way that the actual experience had, yet he understood that to his parents these were likely the key indicators of his success. Drawing his certificate to display in the exhibition was therefore another way that his art was a process in navigating the space in between his convictions and those of others in a poetic and sensitive

OK's scepticism of the art-school-exhibition format stems from his view that these events are ‘seen through the prism of studying art, rather than a demonstration of independent practices’ (OK interview, 2022). Although he has not stated this, it is certainly possible to identify correlations between the graduation show and another typology of display and gathering relevant to his field: the street art festival. One is normally a requirement and the other optional, yet both offer a degree of public exposure and association (to an institution, other artists, an artform, or a place) that might render the decision not to participate a personal and professional disservice. However, especially contentious for artistic subcultures, these events also seek or serve to organise, categorise, and legalise them. Street art has fast become an accepted – and often commissioned – force, harnessed in many major cities across the world by real-estate developers, politicians, and projects seeking to ‘beautify’ public spaces for any number of good, nefarious, or obscure intentions, no less so in Russia under the state's policy of blagoustroistvo, literally translatable as the ‘construction of a blessing’ (Murawski, 2018). While in many ways this beautification – and essentially, gentrification – of outdoor areas may align them with global visions of sustainable urban paradises, or make them more attractive to certain segments of local and visiting populations, it also displaces many others and destroys grass-roots habitats due to decisions being forced down from above as to how to treat public spaces that belong to both everyone and no one.

OK's intervention at Carte Blanche, a street art festival held in Yekaterinburg in July 2018, brought to the surface these problematics. Organised by Russian street artists of near-celebrity status such as Slava Ptrk, permission had not been requested from the authorities in line with the intention that the festival be based in the true illegal roots of street art. Nonetheless, the event did not come under any fire for this (perhaps partly because Yekaterinburg is one of the most street-art friendly of all Russian cities), meaning that it might not be preposterous to suggest that Carte Blanche may even have inadvertently complemented blagoustroistvo for how it illustrated the city with figurative murals and photogenic text art statements, all mounted perfectly within their wall canvases. OK headed to the festival in its last days and contributed by illegibly scribbling over parts of these fresh pieces, before having his photograph taken next to them, wearing a mask of his own face in a nod to how underground graffiti artists usually conceal their identities (Figure 9). At first applauded as a radical response, by some scribblings later, it had angered many of the festival artists, who called him to their hostel, where they did not allow him to leave for the whole night while they demanded explanations and that he pay damages for his interventions on their works. To defend private ownership of a work that many might say should be public property from the moment the spray hits the wall (Bonadio, 2018), seems in itself a bizarre stance from supporters of graffiti's illegality. More than three years after this edition of Carte Blanche, Slava Ptrk wrote a long post on Facebook to publicly apologise for this reaction, in which he explained:

Illegality for us was and is not a goal, but a means; a way to do what we want and where we want. […] The fact is that the artistic statements already created seemed to Oleg not radical enough and he decided to make truly ‘illegal illegal street art’, which fully corresponds to the maximalist precepts of the festival manifesto […], testing the boundaries of what was permitted, our ideology and our strength. And we must admit, unfortunately, we did not pass this test at that moment […] [as] preserved for posterity on a video shot by Oleg (you can find it on his website). […] In the morning, Oleg left Yekaterinburg, and in a few days the festival participants and I returned all the works to their original state. Together with the other organizers of Carte Blanche, the (incorrect) decision was made to ‘erase’ this episode and any mention of Oleg from the history of the festival. With this post, I publicly apologise to Oleg Kuznetsov and admit that I was wrong in the situation that has developed on Carte Blanche […], this cold war between two artists without purpose and meaning is not needed (I hope) by anyone. Artists should not fight each other, as Malevich said.

Mistakes must be acknowledged.

Freedom of expression is above all.

Censorship is not allowed.

OK has also at times made interventions to the works of other artists, that likely happened without comment as they were not fresh pieces made by festival colleagues. These come in the form of his stick-figure logo (composed of his initials) which crops up seeming to surrender before – or perhaps attempting to stand strong and block – an advancing tank or soldier with his bayonet raised. Subtitled ‘Collaborationism’ (Figures 10 & 11), these unagreed collaborations with other artists have added new meanings and context. Graffiti truly is a world of layers (Andron, 2019): of buffs, collabs, interventions, and the erosion of surfaces revealing a new canvas beneath or perhaps reaching their limits, that cover up as much as they are on the top. Sometimes OK's graffiti is so high, low, small, or buried that no one can see it. The covered or hidden is another key facet within OK's practice: after hiding in plain sight as a council worker at the Kurskaya Wall or behind a mask of his own face, painting in little-seen locations such as an old train carriage near his dacha, or making small marks in hidden corners, for ‘Underground’ (2020), OK dug a hole in a field, sprayed his tag on one of its muddy walls, and filled it in again (Figure 12). The question of whether it is possible to make graffiti where nobody sees it – quite literally in this case because it is buried, and by now has more than likely been completely disintegrated by the wet earth – makes us reflect once again on whether graffiti equates to its product or its process, all the while juxtaposing labour against results.

Another subtle, near invisible, refilling of a space constitutes the work ‘Self-Collage’ (2021), except this time OK is in the centre of town, intrigued by the communal practice of workers. Just as Kirill Kto was cutting eye shapes out of banners a couple of generations of Moscow street artists prior, or even before that, when Brad Downey cut a heart out of tarpaulin covering scaffolding on an Aberdeen building for ‘Ladder Stick-Up’ (2007), OK cuts shapes out of material covering building renovation works (Figures 13 & 14). Usually circles, he puts them back, albeit rotated slightly, carrying out double the labour of the worker whose job it is simply to patch up holes. It is a delicate play of poetics in public space, a lesson that adornment doesn’t have to come from big, bright, commissioned murals, or through adding something to make a collage. These interventions might be read also as a metaphor for the economy of sustainability, the accessibility of art, and of making something out of what you already have, even just by viewing it from a different angle and refilling a space with something that was already there.

Also oddly poetic are his ‘Scribblings’ (2017–2020), sprayings on walls that appear rather like the process of trying to get a ballpoint pen working at huge dimensions, at others resembling signatures or doodled diagrams crossed out, or simple tags repeated and tangled in bunches and bowers (Figures 15 & 16). These non-linear, non-verbal musings are an intriguing contrast to the text art of some of OK's (near-contemporaries, such as Tima Radya, who plants poetic or philosophical phrases on buildings and billboards – spaces that in the Soviet period were often dedicated for state-mandated slogans of iron encouragement, or both then and now to advertising – often with loaded meanings but that nonetheless can also be enjoyed superficially. Appearing mostly in similar places to these, OK's scribblings seem to be unfinished, yet also unstarted; the physical production (that never culminates in a product) of a moment perhaps in thought, or of boredom and distraction, of connecting with space, or of whatever comes with feeling the nozzle under one's fingers.

About the time of writing, OK says, ‘it's really hard to think of your own stuff right now, but if you experience creative energy, you can’t allow yourself to do something else. I don’t want to become an artist who just produces – it's not important. I don’t consider myself a political artist, but sometimes there's a really thin line and it's very hard to make something poetic and indirect to the topic you’re touching upon.’ He may indeed not be overtly political, but there is a great deal of what one could certainly interpret as socio-political thought, action, and reaction surrounding his practice, whether it is invisible labour with no discernible result, presence in and ownership of the commons, communal work, reclaiming power and reminding us all what graffiti used to be and now ever more rarely is, i.e., exerting the autonomy to do things because one wants to do them and without having to find a functional or aesthetic point to them within society's norms.

OK's work is a world of spaces in between, not of the empty kind, but rather that ‘thin line’ underscoring the poetry of unique moments, and the places where processes and actions play out. The space between a spray can and a surface, between an artist and a wall, street art and photography, original and reproduction, text and scribbling, reality and documentation, one layer and the next, the ephemeral and the eternal, showing and concealing, private and public, absence and filling, solo and collaboration, illegality and conformism, the power of the people and the power of authority. Some of these might appear to simply be polar opposites, or different states, but in OK's practice, so much happens between these spaces that most of us would not even stop to think about. Yet there are occasional suspicious onlookers who stop to watch people paint walls, take note of the spaces they will never paint, or ponder all manner of other things of which we just don’t see the product. It is just a part of process: it is OK.

All figures courtesy of okuznetsov.com

Elisa Bailey is currently based in Madrid, where she is Head of the Curatorial Department in a company dedicated to museum-making, experience design, and the creation of curatorial and educational projects in the cultural field. She has worked as a Curator, Researcher and Interpreter in Museums across Europe and the Middle East since 2010, previously living in Italy, the UK, Russia, France, Oman, Cyprus, and Austria.She has a BA in Modern Languages from the University of Cambridge, an MA in Contemporary Art and Politics from the Courtauld Institute of Art (University of London), and specialist study from the University of Cyprus and the University of Harvard's Centre for Hellenic Studies in Nafplio, Greece. She is currently a member of the teaching Faculty at the Barreira School of Art and Design in Valencia, Spain. As Founder and Curator of the Rise Rosa Rage Archive, Bailey's main research interest is the figure or role of the artist and the martyr in communities undergoing or emerging from conflict or oppression, alongside the socio-political graphic production particularly of Southern and Eastern Europe, the Middle East and Latin America. Her research on protest groups across the USA in the 1960s was published in You Say You Want a Revolution?, the book accompanying the Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition of the same name, for which she was Assistant Curator.

- 1

See also Nuart Journal, 1(1): 65-80, where OK shared images of this work and his statement, as well as Kurskaya Wall (Kuznetsov, 2019).

- 2

Examples can be found all over the world, for example in the USA, see: www.forbes.com/sites/wendyaltschuler/2020/03/23/americas-mural-magic-how-street-art-can-transform-communities-and-help-businesses/?sh=3c9d3ec41739; in Brazil: blogs.lse.ac.uk/latamcaribbean/2017/04/20/graffiti-vs-the-beautiful-city-urban-policy-and-artistic-resistance-in-sao-paulo/, and in Iran: ajammc.com/2014/03/30/a-mural-erased-urban-art-mashhad/

- 3

Slava Ptrk in his Facebook post of December 31, 2021, written in Russian originally with translation provided by Facebook and sense-checked by OK.

A primary source throughout the article were conversations between Oleg Kuznetsov and Elisa Bailey in 2022. Other literature referenced directly or for further interpretation of some of the topics covered includes:

Andron, S. (2019) ‘Enter the Surface-Interface: An Exploration of Urban Surfaces as Sites of Spatial Production and Regulation’, in: Verhoeff, Nanna, Sigrid Merx & Michiel de Lange (eds), Urban Interfaces: Media, Art and Performance in Public Spaces, Leonardo Electronic Almanac 22(4) [Online] Accessed April 6, 2022. www.leoalmanac.org/enter-the-surface-interface-an-exploration-of-urban-surfaces-as-sites-of- spatial-production-and-regulation-sabina-andron/.

Bacchi, U. (2019) ‘No sex and drugs: Moscow regulates graffiti, but who owns the streets?’. Reuters [Online] Accessed March 22, 2022. www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-art-graffiti-idUSKCN1UZ1CY.

Blanché, U. (2018) ‘Street art and photography: Documentation, representation, interpretation’. Nuart Journal, 1(1): 23–30.

Bonadio, E. (2018) ‘Street art, graffiti and the moral right of integrity: Can artists oppose the destruction and removal of their works?’ Nuart Journal, 1(1): 17-22.

Hansen, S. (2018) ‘Heritage protection for street art? The case of Banksy's Spybooth’. Nuart Journal, 1(1): 31–35.

Kuznetsov, O. (2018) ‘Kurskaya wall, Moscow’. Nuart Journal, 1(1): 67–82.

Kuznetsov, O. (2019) Kurskaya Wall. Moscow: Invalid Books.

MacDowall, L. (2006) ‘In Praise of 70K: Cultural Heritage and Graffiti Style’. Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, 20(4): 471-484. [Online] Accessed April 2, 2022. www.academia.edu/6770111/In_Praise_of_70K_Cultural_Heritage_and_Graffiti_Style.

Merrill, S. (2014) ‘Keeping it real? Subcultural graffiti, street art, heritage and authenticity’. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 21(4): 369–389.

Murawski, M. (2018) ‘My Street: Moscow is getting a Makeover and the Rest of Russia is next’. In The Calvert Journal. [Online] Accessed April 7, 2022. www.calvertjournal.com/features/show/10054/beyond-the-game- my-street-moscow-regeneration-urbanism.

Ponosov, I. (2018) Russian Urban Art: History and Conflicts. St Petersburg: Street Art Museum.

Ponosov, I. (2021) ‘Russian Urban Art: Poetry, Philosophy, and Manifestos in the Streets.’ Brooklyn Street Art [Online] Accessed March 13, 2022. www.brooklynstreetart.com/2021/06/01/bsa-writers-bench-igor- posonov-with-poetry- philosophy-manifestos-in-russian-streets/.

Stavrov, K. & Kuznetsov, O. (2018) Buffantgarde. St. Petersburg: Invalid Books.

Young, A. (2014) Street Art, Public City: Law, Crime and the Urban Imagination. London: Routledge.

Zaitsev, A. (2018) Brighter Days are Coming, exhibition catalogue. St Petersburg: Street Art Museum.