Unauthorised marking of pavements is a form of graffiti that is seldom discussed but, despite its ephemerality, there is ample evidence for the existence of chalk and whitewash writing on roads and footways during the last century or more. I investigated one short era, the tumultuous Great Depression years of the early 1930s, and found that pavement graffiti had a significant role in Australia's urban landscape during that time.

Introduction

Writing on pavements is a traditional form of public expression worldwide. Since ancient times there have been people who choose to communicate by making marks on footpaths (sidewalks), roadways and town squares, and for the last 170 years or more this horizontal graffiti, both official and unofficial, has contributed to the increasingly dense textualisation of public space in the city. There exists a great body of research dealing with the worldwide phenomenon of urban graffiti of the kind that has proliferated since the 1960s, but in this article I aim to contribute to the recognition of antecedents to 1960s graffiti and, specifically, to locate pavement graffiti in that history. Although I have concentrated on a short span of years, 1930 to 1934, in a particular English-speaking country, Australia, this study augments current discussions about the use and meaning of public space.

My previous articles on the largely overlooked subject of pavement graffiti have mostly been based on the photo-graphs I have taken over the past 20 years. But for this present project I set out to find evidence of informal writing on Australian public pavements in earlier times. Other researchers have embarked on similar projects and have discovered physical relics of old graffiti. Katherine Reed (2015), for example, has studied surviving American Civil War graffiti left by soldiers in churches, courthouses, caves, and houses in Virginia, USA. And for her book The City Beneath, Susan A. Phillips (2019) photographed century-old pencil, charcoal, and scratched graffiti hidden under the bridges and in the drains and culverts of Los Angeles.

But I wanted to find evidence of text that was not preserved by its concealment in private or hidden places. I was looking for inscriptions made on very public surfaces in an ephemeral medium. Pavement graffiti, usually hand-written in chalk – either in stick form or as liquid whitewash – was vulnerable to rapid and permanent obliteration, either by passing traffic, or weather, or deliberate erasure. Evidence of its existence would have to come from photographic or written records made at the time it was inscribed.

It is worth noting here that the term ‘graffiti’ was originally coined in the mid-19th century to describe recently discovered inscriptions at ancient sites like Pompeii (Champion, 2017). As a word that referred to unauthorised contemporary inscriptions it did not come into widespread usage in the English language until the mid-20th century. Used in this way it does not appear in more than a handful of Australian publications, nor in any image catalogues, until 1969. Consequently it was almost pointless for me to search for ‘graffiti’, let alone ‘pavement graffiti’, in Australian digitised databases. But when I became inventive with search terms I was overwhelmed with results, mainly from newspapers. Countless news stories and commentary columns referred to ‘notices’, ‘advertisements’, ‘announcements’, and ‘signs’ chalked or whitewashed on roads or footpaths in the decades between 1850 (when Australian footways were first paved) and 1970. This showed that pavement inscriptions have been a visible and newsworthy element of the public landscape since the beginning of urbanisation in Australia.

Depression graffiti

Because my search of more than a hundred years of digitised newspapers was producing an unwieldy number of results, I decided to concentrate on just one short time span, the Great Depression years of the early 1930s. There were several reasons for choosing this era, but mainly it was because this was a time of great hardship and financial inequality, civil unrest, and political turmoil.

Australia was badly affected by the worldwide economic crisis and many people suffered. Physical relief was offered by community-based charities while spirits were bolstered through sport and social events such as dancing, and picture shows (cinemas). But businesses collapsed and retailers struggled to find customers. Unemployment rose astronomically. Dissatisfied with the limited aid provided by federal and state governments, some people turned to the revolutionary promises of the Communist Party of Australia (CPA) and the practical help offered by its newly formed offshoot, the Unemployed Workers Movement (UWM). There were conflicts within and between the Australian Labor Party (ALP), the Nationalist Party, trade unions, the Communist Party, and ultraconservative groups like the New Guard. As Phillips (2019: 11) notes, ‘graffiti flourishes in constrained, disrupted or hostile circumstances’ and it is certainly true that graffiti, and in particular pavement graffiti, flourished during the Depression years.

It was not only political activists that used the pavement as a noticeboard. A 1931 article in The Sydney Morning Herald remarked:

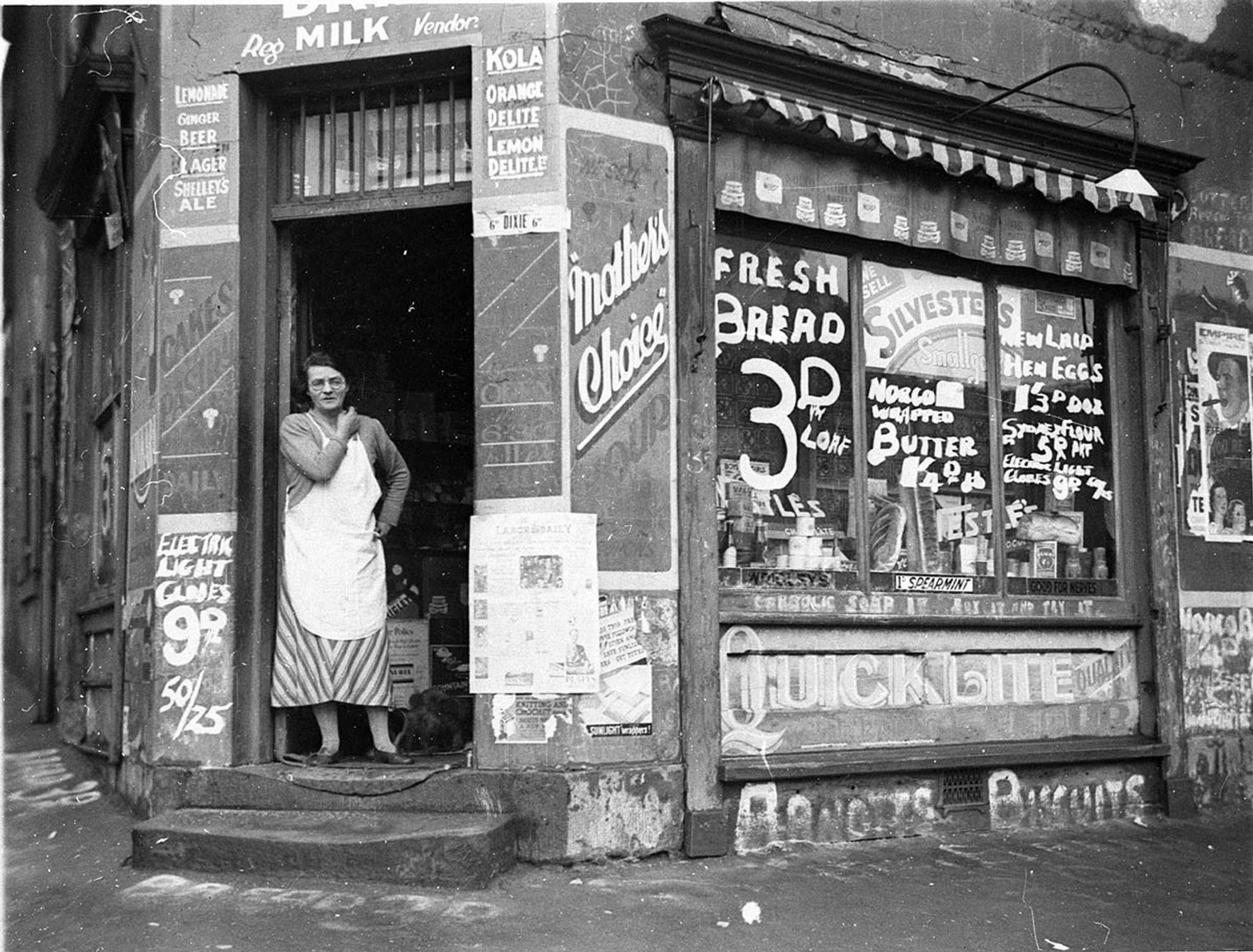

It would appear that in spite of the depression the chalk vendor is doing quite a brisk business. All over the suburbs there are notices chalked on the footpath about evictions, public meetings, rallies, and speeches. Enterprising shopkeepers have also taken up the idea that footpath advertising is cheap and easily obtainable. Some of the councils are beginning to object to this new chalk era…

A similar article in The Age added to the list of foot-path scribes:

Cheap advertising is adding to the worries of municipal councils […] Every morning footpaths are found to bear announcements in chalk or limewash of meetings, dances, and other gatherings interspersed with particulars of shop bargains. “Printers require money for their work, although they do not always get it”, remarked one [mayor], “and the tendency is to avoid expense. Hence this outbreak.”

I also chose these dates because it was during this time that the chalked copperplate word ‘Eternity’ began appearing on Sydney footpaths. Even if Sydneysiders know nothing else about pavement graffiti, they know of former no-hoper and Christian convert Arthur Stace, who first bent down to write his one-word sermon in 1932 (Williams & Meyers, 2017). ‘Mr Eternity’ became an iconic figure in the Sydney imaginary. His mysterious anonymity, the latent meanings in his succinct message, and his persistence in continuing to chalk that word all over Sydney for more than 30 years seemed to touch something deep in the city's psyche. But, as this project reveals, when he was first moved to use the piece of chalk that happened to be in his pocket, messaging on the pavement was not an unusual practice. Nor was he the only evangelist to proselytise on the pavement.

Although not necessarily exhaustive, my searches of Australia-wide newspapers for the period 1930 to 1934 yielded a remarkable 320 articles that referred in one way or another to inscriptions on pavements. Over half of these were published in 1931. There were even one or two grainy photographs. But using newspapers as my sole source meant that there were inevitable biases in my results.

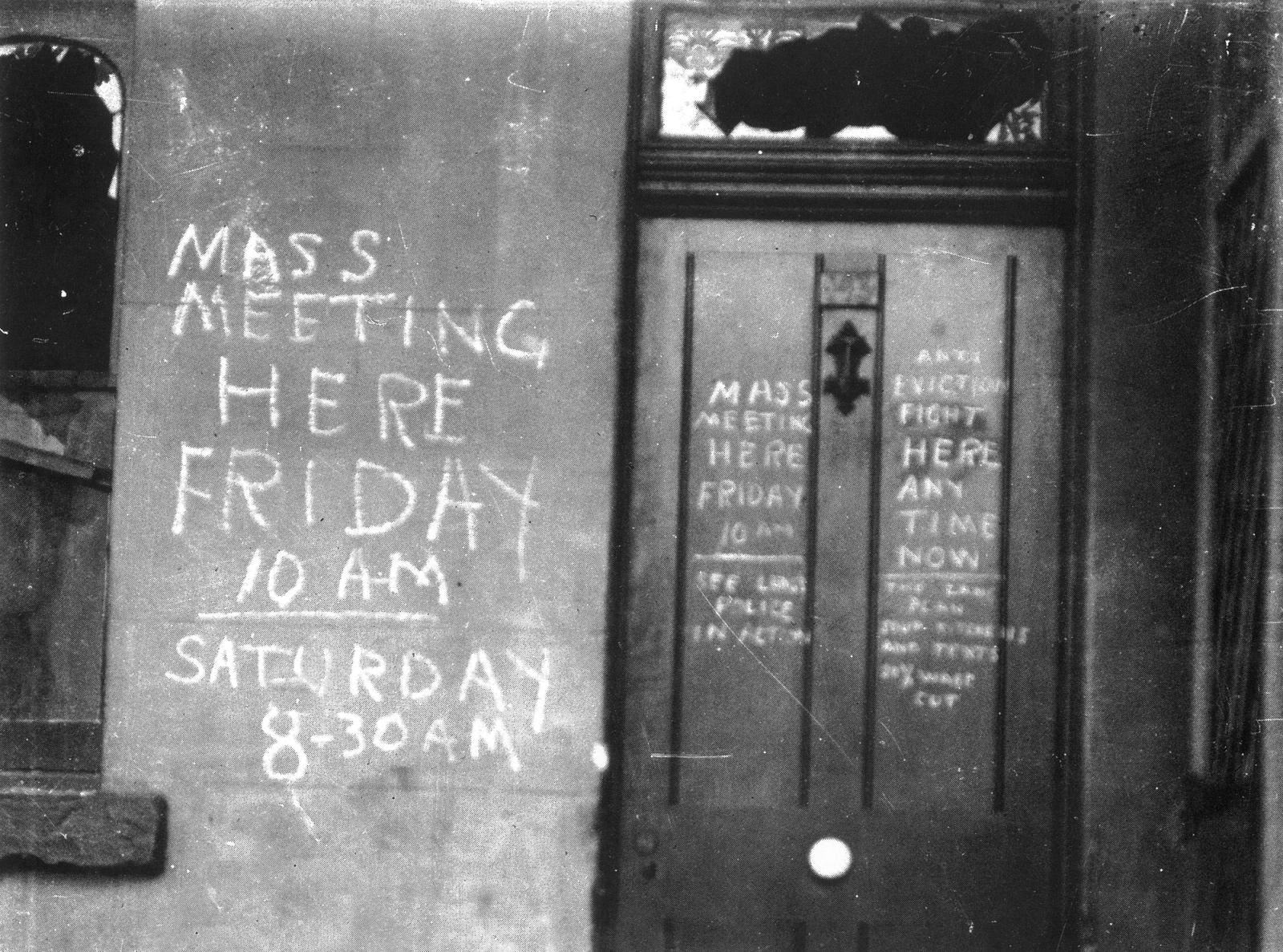

A majority of the stories that mentioned pavement signs had to do with the newsworthy political turmoil of the day – elections, working class militancy, union meetings, calls for a general strike, anti-eviction campaigns, bread raids, hunger marches, arrests, and prosecutions, as well as rallies and demonstrations organised by the Communist Party and the associated Unemployed Workers Movement. How these stories were reported depended in turn on the political biases of the newspapers themselves, from the mainstream conservatism of the Argus (Melbourne) and the Sydney Morning Herald, to the far left leanings of the Communist Party's Workers' Weekly.

Advertisements for small businesses, entertainments, and charity events are mentioned in the papers less frequently, and sometimes the only reason they are referred to at all is because political activists who were prosecuted for writing on the pavement claimed that they were being treated unfairly in comparison with shop or cinema owners who did the same. Frivolous or personal chalkings are only occasionally alluded to, but judging from a few casual remarks in the papers I suspect this means that they were inconspicuous because of their familiarity. There were, for instance, jokes (and jokey alterations of other people's notices), New Year greetings (apparently an annual ritual), children's scrawlings and games, and obscenities (although the actual content of these is never mentioned in the papers). There were also articles about pavement artists who drew pictures and made a living from the coins tossed down by passers-by, but I have written about these people elsewhere (Hicks, 2021) and have not counted them in my tally of articles about unauthorised ‘pavement graffiti’.

Despite the biases inherent in my research, it is possible to get an idea of the role that pavement graffiti played in public life at the time. For this present article I have chosen a sample of newspaper stories to show how pavement inscriptions were regarded by law enforcers, civic authorities, the general public, and the chalkers themselves.

Crime

The state of roads and footpaths is a matter of civic pride. In keeping with their prime responsibilities of ‘roads, rates, and rubbish’, it was the duty of local government councils to construct local roads and footpaths and keep them safe, unobstructed, clean, and presentable. Pavement graffiti, especially boldly drawn notices like the example in Figure 3, transgressed on all counts. They were hazardous, not least because they scared cows and frightened horses; their foul language was unfair to women and children; they were obstructive and caused traffic jams and bottlenecks (presumably because people stopped to read them or tried to manoeuvre around them); and, worst of all, they were unsightly, being variously referred to as ugly, disfiguring, hideous, defacement, vandalism, and offensive to civic order.

Well before the 1930s, most councils had in place ordinances or by-laws that prohibited unauthorised advertisements on council property and thus, in effect, prohibited writing on pavements. The Sydney Morning Herald article about writing on the footpath (quoted earlier) continues by setting out the general form of these ordinances and explaining why implementing them was difficult:

[…] Some of the councils are beginning to object to this new chalk era, and desire to put the law in motion in regard to it. There is an ordinance available, provided it can be enforced: “Except by permisison [sic] of the council notices, signs, and advertisements shall not be exhibited in any road upon any tree, bridge, culvert, drain, fence, post, monument, or other work or property of the council.” The footpath is the property of the council, and it would appear as if the ordinance sufficiently met the case. The difficulty is that these signs seem, like mushrooms, to grow up in the night. In order to prosecute, a council must be able to prove that some particular individual (who must be found and named and served with a summons) exhibited the notice on the footpath. It is the old story, “First catch your hare”.

Technically, these ordinances could only relate to defacement of property rather than the content of the notices, but in many cases it was the content that offended. There were councils that quite specifically did not want Communist signs scrawled in their streets. Brisbane Council, for one, broadened the definition of ‘advertising device’ in their relevant ordinance in an attempt to successfully prosecute Communist chalkers. In response, a columnist fumed that, although neither he nor his newspaper had any sympathy with the Communist Party, he objected to

[…] the power now wrongly given to the Brisbane Bumbles or officious employees, to come at ANYBODY on ANY count at all, under pretence of having broken the Council's latest precious “ordinance”. For instance […] the chalked notice on the Council's road, or footpath, asking the public where it will spend eternity, or urging it to be at Blogg's Corner on Mother's Day, could also be used to annoy some perfectly innocent person, or persons – if they can be found.

What this columnist apparently did not know was that street chalkers more innocuous than Communists were already being annoyed – and fined – in other cities and towns all around Australia. Even Mr Eternity (Arthur Stace) was taken in by the police periodically – but let go each time because it was decided that defacing the pavement was an improvement on the petty crimes of his former life (Williams & Meyers, 2017: 146).

Since writing on pavements was a breach of local government ordinances, police would usually consult with the local council before offenders were taken to court to be tried before a police magistrate. But while some councils were strict in seeing their ordinances implemented, others were ambivalent about prosecution. This could create conflict between police and councils, exemplified by a case in Newtown, a working class suburb of Sydney, where aldermen were vocally antagonistic towards police when they arrested two men for chalking a sign about black-banning a particular worksite.

A Lithgow Council meeting reported at length in the Lithgow Mercury, and in less detail in the Sydney Morning Herald, serves to illustrate the quandary that faced aldermen in some local government areas. Lithgow was an industrialised mining town seriously affected by the Depression. Because the town economy was dependent on the wages of workers, people of all classes were sympathetic during industrial disputes and retrenchments (Patmore, 2000: 507).

But by early November 1931, chalked signs had become numerous. Three outsiders had been caught chalking ‘communistic signs’ on footpaths in contravention of the relevant ordinance. The signs said such things as ‘Smash the New Guard’, ‘Join Youths’ Section, U.W.M.’, ‘Soviet Germany This Year’ and ‘Join the Militant Minority Movement’ and the police wanted to know the Council's attitude to prosecuting these men. At its next meeting the Council considered not only the police report about the footpath chalking but also a request from the Friends of the Soviet Union to hold a march in the streets on the anniversary of the Russian Revolution. The request about the march was granted with the majority of aldermen agreeing that ‘it was only British justice to allow every party or organisation a fair chance’.

But with regard to the chalked signs, there was a much longer debate. One alderman did not object to them as such but thought ‘it was the objectionable terms that were added after that mattered’. Another considered that the writings did not matter much and ‘until Council had a complaint from ratepayers it would be as well to defer action’. Several were worried that if they enforced the ordinance in this case then they would have to stop every-one from chalking signs, including the town's business people and ‘shopkeepers who chalked […] on foot-paths that ice cream and other articles were for sale’. The writings had been going on for years, said another, ‘and probably the present matters had been brought up by the persons who objected to a certain political organisation’. After further rowdy debate it was decided that there should be no prosecution in this case but that a warning should be inserted in the press stating that, in future, action would be taken against offenders who did not first obtain permission of the Council. This notice was duly published in the Lithgow Mercury.

At the following Council meeting, aldermen discussed a letter that had been received in the interim from the local branch of the Communist Party seeking the right to chalk signs on the footpath as this was the only means the branch possessed of advertising. It was decided that the request be referred to the Hall and Parks Committee to see if it was possible ‘to give these people a set place to advertise their meetings’. These matters were of general interest in the town, although not necessarily taken too seriously. That same month an entertaining mock trial was held as a fundraising event at the Lithgow Methodist church hall. About 150 people were charged with ridiculous offences and offered equally ridiculous defences. A mine manager, for example, was charged with selling black coal. And an alderman was charged with aiding and abetting footpath chalkers.

Punishment Lithgow's leniency might have been an exception because there were numerous cases elsewhere of men, and occasionally women, who were prosecuted for writing on pavements. Thanks to the practice by news-papers of reporting cases in the police courts, it is possible to catch glimpses of court proceedings and to learn what fines – or gaol terms in lieu – were handed down.

For example, a South Melbourne man declined to appear in court to answer a charge of writing a footpath advertisement reading ‘Demonstrate against Fascism and war’. He had told the arresting police constable, “I will say nothing. I am a Communist and I will take what is coming to me”. In his absence he was fined 30/- (one pound and ten shillingsthirty shillings). In another case in 1931, three men were each fined 10/- with 8/- costs (18 shillings in all) for having chalked the words, ‘Demand double dole, and do away with dole tickets’ on the footpaths of Marrickville, an industrial suburb of Sydney. This was at a time when the average weekly wage was between £3 and £5. The government's sustenance payment for unemployed men (the dole) was much less and the fine amounted to the best part of a week's dole.

In Brisbane in 1932, the Police Magistrate fined a youth 30/- or seven days imprisonment in default, for ‘writing an advertisement on the footpath about a mass meeting of the unemployed’. “I'll take the seven days, sir”, replied the youth’. In fact, many of those caught chose the option of a sentence (and consequently a prison record), but it is seldom noted whether they did so out of defiance, or because they could not afford to pay the fine, or because gaol meant a bed and meals for a few days (or indeed, all three). Nevertheless, working people and the unemployed were angry about the gaolings. In 1931 the East Marrickville branch of the Australian Labor Party passed a motion that:

This branch of the A.L.P. views with disgust the action of the Marrickville Council in showing its vindictive-ness against members of the working class in prosecuting them for chalking on footpaths and advertising working class meetings, in the same manner as shopkeepers have been advertising their goods for many years.

There were offenders who seemed genuinely ignorant of by-laws prohibiting pavement notices; others feigned ignorance. When a feisty Fremantle man was asked by the arresting constable if he had permission to write the advertisement, he replied, ‘I thought it was quite alright, and no one had given me permission’. Some – the midnight chalkers – did their work furtively, others were either naïve or openly defiant, sometimes relying on passers-by not to inform on them. Magistrates were unmoved either way. When one chalker declared that he did not consider the writing an injury to the pavement the magistrate retorted, ‘Well, what right have you to write on the pavement? It doesn’t belong to you’.

It is true that most arrests were of people writing political signs, usually slogans or notices about rallies and meetings. However, there was also the occasional surprising prosecution, such as when the proprietor of a cafe in Parkes (a rural town in New South Wales) was charged by the council with having inscribed an advertisement on the footpath. The case was so unusual that the story was syndicated in a number of rural newspapers, opening with the warning, ’It may not be generally known that advertising on footpaths is illegal, and persons disfiguring any footpath by chalking or painting advertisements thereon are liable to be fined’.

The public response to footpath chalkings, as far as it is recorded in the newspapers, was varied. While most people did not voice their opinions publicly, there were some who violently opposed the prosecution of chalkers and others, even in the same town, who thought the opposite. This no doubt reflected their own political leanings.

For instance, in Broken Hill, a remote mining city, a man was gaoled for two days in default of paying a fine, after a constable caught him starting to chalk a notice, ‘Mothers protest against the re—’ on the footpath. In response, some 600 unemployed men held a protest march through town singing ‘The Red Flag’. At the town hall their leaders commandeered the balcony where they made speeches protesting against the gaoling of the man and condemning the town clerk and Labor aldermen. But at the man's trial the town clerk had pointed out that this was the first prosecution of its kind in Broken Hill and it had only been pursued because ‘numerous complaints had been received in regard to the practice, which was becoming exceedingly prevalent of late’.

People in Lithgow, too, finally decided they'd had enough of ‘footpath chalking propagandists’ and took matters into their own hands. Lithgow was the mining town where aldermen had been at pains to be fair to Communist chalkers. But a year later, when white-painted signs about May Day celebrations appeared on the asphalt of the main street, ‘obliterators’ tried to write over them, chalking ‘church burners!’ and other hostile messages.

Meanwhile, in suburban Sydney, good citizenship was on the mind of a columnist who wrote in his local Hurstville newspaper:

Vandals with white-wash brushes and chalk are still making tarred footpaths and roads, not to mention walls, in this district hideous and unsightly […] If they are residents of the district they are certainly not worthy citizens. Civic pride seems to be a trait not understood by them.

Ostensibly, then, it was pavement graffiti's affront to civic orderliness that troubled local governments, the police, magistrates, and the community at large. But underlying these concerns was a fear of the threat to social order that the Communists' messages represented. Nevertheless, despite the prosecutions and the sometimes vehement objections to their signs, Communists and other political activists continued to use the pavement as a site for broadcasting their agendas. The reason was evident: their publicity worked.

Effectiveness

In the early days of the Depression, Labor Call (the official organ of the Political Labor Council of Victoria) reported that the unemployed of Melbourne were holding meetings in increasing numbers, noting that ‘The mode of advertising is per medium of chalk on the footpaths, and it seems fairly effective’. The subsequent irruption of pavement writing across Australia attests to its effectiveness, or at least to a belief in its effectiveness. It was an advertising tactic that had been used for decades by theatres and small retailers but activists, especially those from the Communist Party and the United Workers Movement (UWM), took it to extremes.

As a communication tool it was cheap and required little more that a box of chalk or a bucket of whitewash and willing bodies. It did not encroach on anyone's private property. It was very visible publicly, especially in the days when people walked a great deal more in their everyday lives than they do today. ‘If this sort of thing extends’, quipped one newspaper writer, ‘the poor pedestrian who now walks to and from work to save tram fares will get some little entertainment to lighten his weary tramp’.

In many cases it was the only way that activists could make written announcements. A defendant who had been caught chalking a notice about a May Day meeting in Fremantle was reported as declaring, ‘The notice was not any different to other notices like “wet paint”. My ad. was written in chalk. Further all other advertisements are blocked by the Capatalistic [sic] Press.’

An added feature of footpath writing was that it facilitated a quick response in urgent situations. Years after the event, Adam Ogston, a local Communist Party official at the time, recalled one of the eviction battles he took part in:

I was sitting in the Party office in Granville [a Sydney suburb] with Angus [Ogston] and Jock [Croft] when word came in that a woman and her children were to be evicted that afternoon from a house in Blaxland St. Immediately we went to the scene, where the tenant told us that she was expecting the bailiff and police at any moment. We had very little time, so we got out with a biscuit tin as a drum, and around the streets we went, calling upon everybody to come to the eviction and chalking notices on the footpaths. In no time, a large crowd had gathered at the house (Ogston, 1960: 6).

Many authors have written about the Depression-era eviction battles but few, if any, have acknowledged the role that footpath writing played in those events. With the economic crisis worsening, the numbers of unemployed rapidly rising, and the relief coupon system not providing any cash for rent, many working class tenants fell behind in their rent payments. Evictions became an everyday occurrence in cities around Australia. The UWM was the leader in resisting the practice of eviction, adopting tactics that ranged from deputations to landlords and agents to vandalising houses that had been evacuated. During 1930 and 1931, there was a series of confrontations, where UWM members would occupy houses whose tenants had been served a notice to vacate, and use footpath chalking to mobilise large numbers of people from the surrounding district. Bailiffs would be met in the street by crowds numbering in the hundreds. Sometimes these measures were enough to avert an eviction. One such event in East Sydney was reported in the Daily Telegraph:

Declaring that the Italian tenants will be evicted only “over our dead bodies”, a large party of unemployed have garrisoned a house in Chapel Street, Surry Hills. Mr. S. Papatonian, with his wife and ten-months-old baby, were threatened with eviction yesterday morning; but news of their plight was chalked on paths in the vicinity. When bailiffs arrived, the narrow alley was packed with people, and the door was guarded. Police were sent to the scene to prevent trouble; but, it is stated, they made no attempt to assist the eviction; it was not their job.

Reporting on the same event, the Sydney Morning Herald noted that,

Streets in the vicinity were disfigured with chalked notices appealing to the unemployed to rally around the home and prevent the bailiffs from executing the eviction notice […] The bailiffs came, and went away […] A roster was then prepared, and the defending forces were divided into shifts. They will guard the house until the matter is settled to their satisfaction.

By mid-1931 the situation had escalated in Sydney after police, no longer merely watchful observers, were enlisted to enforce evictions. Confrontations became battlegrounds with busloads of police brought in. Stones and missiles were thrown and shots fired. The most infamous of these riots happened in Newtown and came to be known as the Siege of Union Street. A hostile crowd in the street, once again drawn by chalk notices (which were permitted by Newtown Council), shouted and threw stones as a fierce battle took place inside the house between police and occupiers. Injuries, arrests, and a court case ensued, but this was to be the last anti-eviction demonstration in Sydney. Within a month, an announcement was made that the state government would introduce anti-eviction legislation. Pavement signs had been an integral part of a grassroots campaign that forced a change in the laws on eviction.

The eviction crowds, sometimes numbering a thousand or more, were tangible evidence of the effectiveness of footpath notices. No doubt similar notices raised attendances at other kinds of meetings and rallies, and played a part in recruiting new members to the Communist Party and the AWM. The chalking of multiple political signs and slogans would have had less tangible outcomes as well, including the affirmation of allegiances amongst those who wrote them, and a demonstration to the wider community of the political groups' strength. Conversely, they might have heightened the antagonism of those opposed to Communism. Other kinds of pavement notices, such as handwritten advertisements for ice cream, milkshakes, euchre parties, and picture shows probably brought positive results, their immediacy and personal touch likely to make them more appealing to locals than professional signwriting or mass-produced posters.

Conclusion

Pavement graffiti altered the appearance of streets in Depression-era Australia. By 1931 there had been an immense surge in the number of unauthorised messages, handwritten in chalk or whitewash, on the footpaths and roads of cities, suburbs, and towns. To a large extent this visual change was brought about by the struggle to bring about social change, with the Australian Communist Party and the Unemployed Workers Movement incorporating the pavement into their radical campaigns.

Until that time, shopkeepers' footpath advertisements had normally been tolerated and election notices were periodically expected, but the Communists' efforts emboldened others to make more use of public thoroughfares as notice-boards. Underlying all this textual activity, whether it involved political slogans, or announcements about cheap bread, or evangelical admonishments, was the assumption that pavements belonged to the public and were – or should be – available for public communication. Messy footpaths were manifestations of desperate times when nothing was normal.

Those ephemeral messages on dusty pavements were conspicuous, newsworthy and, in some cases at least, effective. They represented a threat to both civic orderliness and social order. They took up the time of local councils, police, and the courts. Consequently, they cannot be regarded as incidental curios or mere footnotes to history. Rather, they were integral to the story of public life in Australia during the turbulent years of the Great Depression.

Megan Hicks lives and works in Sydney, Australia. She is an Adjunct Fellow with Western Sydney University and her research covers aspects of urban culture, with a particular interest in text in public places and the pavement as a cultural artefact. Hicks also works as a freelance museum consultant. Her blog Pavement graffiti and other urban exhibits is at www.meganix.net/pavement/.

- 1

Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies was an early adopter. When supporting the continuing ban on Brendan Behan's The Borstal Boy in 1959, he remarked that it seemed to him the book ‘was almost a collection of what the Italians called “graffiti” – that was to say, things written on walls in certain places by adolescents’. (‘No intervention to release banned books’, Canberra Times, February 19, 1959: 12)

- 2

I am indebted to Trove, the resource managed by the National Museum of Australia that connects and makes accessible digital collections from many Australian sources.

- 3

The term ‘pavement’ can be problematic in that usage varies across English-speaking countries and even within these countries. Paved footways laid down beside roadways, for example, are usually called pavements in Britain, sidewalks in North America, and footpaths in Australia. Because my source material comes from Australian publications I have generally followed them in using the terms ‘footpath’ for paved footways, ‘road’ or ‘roadway’ for paved surfaces for horse and vehicular traffic, and ‘pavement’ as a collective term that refers to either of these.

- 4

‘Local Government. The writing on the footpath’, Sydney Morning Herald, July 30, 1931: 4. The term ‘new chalk era’ is a reminder that Rennie Ellis described the 1970s as a time of the ‘great graffiti renaissance’. Rennie Ellis and Ian Turner's books Australian graffiti (1975) and Australian Graffiti Revisited (1979) were among the very few projects to photographically document the graffiti of that time. Ellis's pictures mostly show political and protest graffiti on walls, but there are a few examples of pavement graffiti as well.

- 5

‘Sydney day by day’, Argus (Melbourne), July 31, 1931: 6.

- 6

Many authors, including myself, have reflected on Stace's legacy. See, for instance, Hicks, M. 2011, ‘Surface reflections: personal graffiti on the pavement’, Australasian Journal of Popular Culture, 1(3): 365-382; Hicks, M. 2015, ‘Words of regret’, Sturgeon, 3: 48–53.

- 7

For example, covering a murder story a reporter noticed that ‘[b]efore the house, on the asphalt footpath, some wandering evangelist had chalked the text: “Your sins shall find you out.”’ (‘Saw brute husband shot dead. Surry Hills tragedy’, Sun (Sydney), October 18, 1931: 1).

- 8

See Young, 2020.

- 9

‘Writing on footpaths. Its effect on cows’, Gosford Times and Wyong District Advocate, March 29, 1934: 4; ‘Writing on footpaths: Communists go to gaol’, Sydney Morning Herald, August 20, 1931: 7; ‘Chalking on footpath. Offenders hard to catch’, Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, March 2, 1933: 2; ‘North Illawarra Council’, South Coast Times and Wollongong Argus, July 17, 1931: 5; ‘Horses shy at signs’, Mirror (Perth), June 10, 1933: 9.

- 10

‘Chalking footpaths’, Sun (Sydney), March 15, 1933: 15.

- 11

‘Local Government. The writing on the footpath’, Sydney Morning Herald, July 30, 1931: 4.

- 12

‘Of making ‘’laws” there is no end!’, Daily Commercial News and Shipping List (Sydney), September 7, 1933: 4.

- 13

In Australia today, as in many other countries, unauthorised and intentional graffiti of all kinds continues to be regarded as a punishable offence. Under the New South Wales Graffiti Control Act 2008, for example, police carry out enforcement and prosecution but local governments are responsible for graffiti removal. In their justifications for removal, local councils refer to graffiti as having a negative impact on community amenity, including pollution, visual pollution, damage to property and perceptions of neglect, poor safety and increased crime (Inner West Graffiti Management; City of Sydney Graffiti Management Policy). However, in 2014 a clause was added to the Graffiti Control Act explicitly permitting the marking of public footpaths or public pavements in chalk. In arguing for the amendment, parliamentarian Ian Cole invoked Arthur Stace. Some Christian groups refer to this clause as ‘Arthur's Law’ (New South Wales Graffiti Control Act 2008 – Section 4 Marking premises or property – Subsection (5); Williams & Meyers 2017: 266).

- 14

‘Footpath writing. Police tread on Council's corns. Aldermen antagonistic”], Mirror (Perth), April 21, 1934: 16.

- 15

‘Defacing Lithgow footpath’, Lithgow Mercury, November 5, 1931: 2; ‘Footpath chalkers’, Sydney Morning Herald, November 6, 1931: 6.

- 16

‘Municipality of Lithgow. Warning’, Lithgow Mercury, November 6, 1931: 3.

- 17

‘Footpath advertising. Communists want it. Council to again consider’, Lithgow Mercury, November 18, 1931: 4; ‘Chalking footpath’, Goulburn Evening Penny Post, November 19, 1931: 6.

- 18

‘Mock trial causes amusement, raises money’, Lithgow Mercury, November 19, 1931: 4.

- 19

‘Wrote on footpath. Man fined at South Melbourne’, Argus (Melbourne), April 28, 1934: 23 (In the same article the Inspector for South Melbourne Council is reported as saying that the offence of writing on footpaths was so prevalent that the Council had offered a reward for the detection of offenders.)

- 20

‘Mustn’t Write On Footpaths!’, Mirror (Perth), December 12, 1931: 18.

- 21

See Laughton, 1932: 194; Beaumont, 2022: 189. In Australian pre-decimal currency in Australia £1 (one pound) was worth 20/- (twenty shillings), so 30/- equalled one pound and ten shillings (or three dollars in decimal currency).

- 22

‘Chalked notice on footpath. Man prefers gaol’, Daily Standard (Brisbane), March 31, 1932: 5; ‘Chose gaol’, Telegraph (Brisbane), March 30, 1932: 9.

- 23

‘A.L.P. Meetings. East Marrickville’, The Labor Daily (Sydney), November 2, 1931: 8.

- 24

“‘Take the days out.” “When do I start”. May Day aftermath’, Fremantle Advocate, July 6, 1933: 4.

- 25

‘Chalking on footpath. Offenders hard to catch. “People not game to report”’, Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate (Parramatta), March 2, 1933: 2.

- 26

‘Writing on roads. Two Cardiff men fined 2/-. Shire prosecution’, Newcastle Sun, October 26, 1932: 6.

- 27

Casino and Kyogle Courier and North Coast Advertiser, May 20, 1931: 3; Northern Star (Lismore), May 19, 1931: 4; The Gundagai Times and Tumut, Adelong and Murrumbidgee District Advertiser, May 8, 1931: 2; The Dubbo Liberal and Macquarie Advocate, May 12, 1931: 2.

- 28

‘Notices on footpath. Man who wrote one fined in Police Court’, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), August 17, 1931: 2; ‘The unemployed. Demonstration today outside Town Hall. March through streets’, Barrier Miner (Broken Hill), August 19, 1931: 4; ‘Barrier unemployed. Take possession of Town Hall’, Sydney Morning Herald, August 19, 1931: 12.

- 29

‘Random notes. (By the Man in the Street). Footpath chalking’, Lithgow Mercury, April 29, 1932: 2.

- 30

‘Vandals in our midst’, Propeller (Hurstville), May 2, 1930: 6.

- 31

In his analysis of political trials of Australian communist and leftist defendants from 1930-39 (which also happens to be based on searching newspaper reports), Douglas (2002) does not specifically mention pavement writing but, in his table of offences, chalking may well be included in his category ‘Bill-posting, leafleting’. Douglas found that magistrates (that is, court officials who dealt summarily with minor crimes like bill-posting or pavement defacement) ‘sometimes made their distaste for communism clear’, especially in the early 1930s, whereas judges presiding over jury trials ‘proved to be masters of decontextualisation, with their judgments impressive for their capacity to transform politics into law’.

- 32

‘Topical’, Labor Call (Melbourne), March 27, 1930: 7.

- 33

In 1932 a box containing 150 sticks of white chalk crayons cost 2/3 (two shillings and three pence) (‘For sale’, West Australian (Perth), May 27, 1932: 21).

- 34

‘Pavement propaganda’, Murrumbidgee Irrigator (Leeton), August 18, 1931 4.

- 35

“‘Take the days out.” “When do I start.” May Day aftermath’, Fremantle Advocate, July 6, 1933: 4.

- 36

I have relied on Wheatley, 1980; Cottle & Keys, 2008; Irving & Cahill, 2010; McIntyre, 2013 and Beaumont, 2022, but even these authors do not mention the footpath notices.

- 37

‘Evict “Only over our dead bodies!”. Bailiffs outwitted’, Daily Telegraph (Sydney), February 28, 1931: 7.

- 38

‘House guarded against bailiffs. Attempted eviction at East Sydney’, Sydney Morning Herald, February 28, 1931: 13.

- 39

‘Jury disagrees. Crown fails to convict’, Workers' Weekly (Sydney), September 18, 1931: 1; Wheatley, 2010: 228.

Beaumont, J. (2022) Australia's Great Depression. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Champion, M. (2017) ‘The priest, the prostitute, and the slander on the walls: shifting perceptions towards historic graffiti’. Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 6(1): 5-37.

Cottle, D. & Keys, A. (2008) ‘Anatomy of an “eviction riot” in Sydney during the Great Depression’. Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, 94: 186-200.

Douglas, R. (2002) ‘Let's pretend? – Political trials in Australia, 1930-1939’, UNSW Law Journal 25: 33-70.

Hicks, M. (2021) ‘The man on the street’. Openbook (State Library of NSW): 18-23.

Irving, T. & Cahill, R. (2010) ‘The anti-eviction war – Union Street, Erskineville’, in: Irving, T. & Cahill, R. (eds), Radical Sydney: places, portraits and unruly episodes. Sydney: UNSW Press: 196-203.

Laughton, A. M. (1932) Victorian Year-Book, 1930-31. Melbourne, Office of the Government Statist.

McIntyre, I. (2013) How to make trouble and influence people: pranks, protests, graffiti & political mischief-making from across Australia. Oakland, California: PM Press.

Patmore, G. (2000) ‘Localism, capital and labour: Lithgow 1869-1932’. Labour History, 78: 53-70.

Ogston, A. (1960) ‘How Party led in dole-days struggles’. Tribune (Sydney), August 17, 1960: 6.

Phillips, S. A. (2019) The city beneath: a century of Los Angeles graffiti. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Reed, K. (2015) ‘“Charcoal scribblings of the most rascally character”: conflict, identity, and testimony in American Civil War graffiti’. American Nineteenth Century History, 16(2): 111-127.

Wheatley, N. (1980) ‘Meeting them at the door: radicalism, militancy, and the Sydney anti-eviction campaign of 1931’, in: J Roe (ed), Twentieth Century Sydney: studies in urban & social history. Sydney: Hale & Iremonger.

Williams, R. & Meyers, E. (2017) Mr Eternity: the story of Arthur Stace. Sydney: Acorn Press (Bible Society Australia).

Young, S. (2020) ‘During the Great Depression, many newspapers betrayed their readers. Some are doing it again now’. The Conversation. April 6, 2020 [Online] Accessed April 20, 2022.theconversation.com/during-the-great-depression-many-newspapers-betrayed-their-readers-some-are-doing-it-again-now-135426.