This is a transcript of Professor Alison Young’s keynote presentation at Art on the Streets II: Art as Intervention, at the ICA London, March 21 2018. In addition to original material, this talk draws on a number of her published works, including Street Art World (2016: London: Reaktion); ‘On Walls in the Open City’ in Andrea Mubi Brighenti and Mattias Kärrholm (eds), Urban Walls: Political and Cultural Meanings of Vertical Structures and Surfaces (2019: London: Routledge), and ‘Illicit Interventions in Public Nonspaces’ in Desmond Manderson (ed.) Law and the Visual (2018: Toronto: Toronto University Press). All photographs, unless otherwise stated, ©Alison Young.

Alison Young: Now, in 2018, how do we think about art on the streets? How do we think about it going forward? Do we think about it in terms of its commodification, its exploitation, its relevance, its irrelevance, its adaptation, commercialisation, its politics – or some would say lack of politics – its charm, its shock value, its history? How can we keep all of those things in mind when we think about art on the streets?

If we pose further questions – what is a street, and what does it mean to talk about art in and on the streets – I think it’s helpful to do so with reference to three different encounters.

First of all, an encounter with the street. I think of the street as a place, and also as a genre, and as a style or an aesthetic. In this section of the paper, I will be talking about images of multiple sites from many different cities. The second encounter is with the wall. The wall is the key surface that we think of when we encounter art on the streets, although it’s not the only one. In this section I am thinking about the wall as a contested location or surface. I’m going to focus on two walls, which are located very close to each other in the neighbourhood that I live in. I’ve been documenting these walls over time, and I am trying to get a sense of how a wall might change and how our encounters with it might also change. The final section is an encounter with the void – by that I mean what it takes to produce a non-image. How an artist might actually make an image which rejects the idea of image. I’ll be focusing on one city, and multiple sites within it.

Encounter 1: The Street

What makes an artwork part of the street? What makes it a street artwork?

We have a stereotypical view of what a street might be. But, of course much art on the street is located on surfaces that don’t really correspond to our idea of the street.

Here we see something that is high above a street in Tokyo (Figure 1, below). Is it still of the street? What makes it part of the street? Why is it not part of anywhere else? This is part of what I meant earlier when I referred to street as a genre, encompassing more than just the conventional built structure.

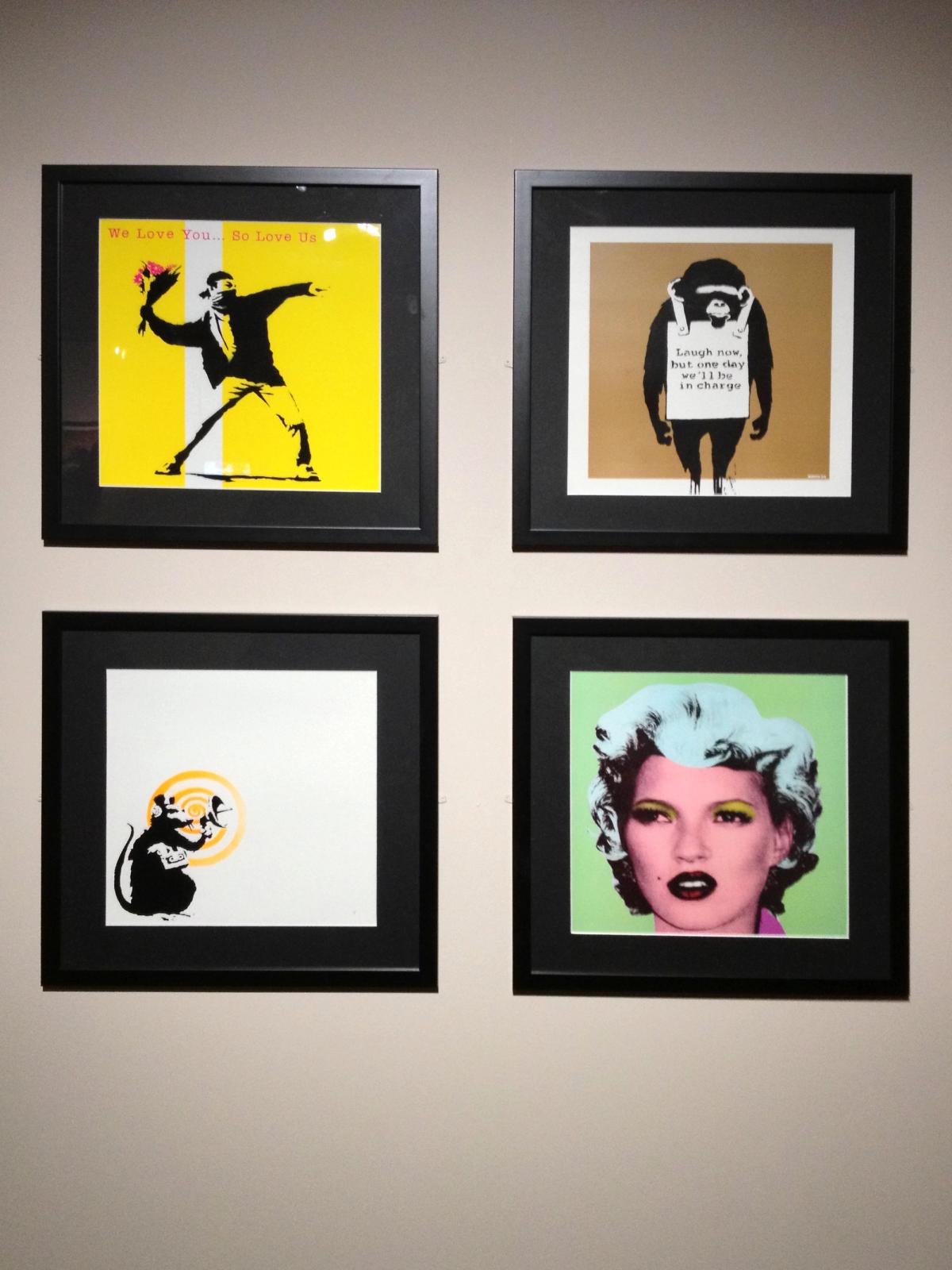

Figure 2. Pure Evil, London coffee shop, 2015; Banksy works displayed in a gallery, 2014

Figure 2. Pure Evil, London coffee shop, 2015; Banksy works displayed in a gallery, 2014

Being of the street gives something a quality that we could call ’streetness’. Elements of streetness might include the location that we find something in – it might be an aesthetic or a style, or it might be the knowledge that we have about the identity of the artist, or the particular location as a popular site for work.

So, location does not necessarily have to mean the street, as in the outdoors – somewhere in a city or a town. If we think about Bansky canvases on display at a gallery or works by Pure Evil displayed on the walls of a London coffee shop (Figure 2) – their connection to the street is greatly reduced, compared with a Banksy on a wall in Williamsburg, or a Pure Evil tag on a wall in London.

The use of canvas or screen printing by the artist, and their display in a gallery or coffee shop, shouldn’t disqualify them from the genre of street art. If we refuse them the status of street art, if we say they don’t belong to the street, then we narrow our ideas about what street art might be. Then we prevent interrogation of the ways in which art institutions and businesses like coffee shops have monetised the idea of the street in street art. It’s not that artworks stop being street art when they are moved into commercial spaces. But perhaps the issue might be that commerce and the street are not that separable, and the apparent immunity from commerce that we thought surrounded early works on the streets has perhaps been shown to be a bit of an illusion in the end.

A viewer might know that an artist or an artwork is of the street, because they know something about a particular spot or something about a particular artist. Some neighbourhoods become known for street art. Some artists become known for using particular spots. Or it may be that someone pays a walking tour company in order to teach them about street art.

There are ways in which the idea of art on the streets can be complicated. The certainties that we have around the genre of belonging to the street, that’s one of the things that I’m interested in and I’d like to look at a few examples where the issue becomes more complicated.

Above we see a very large wall with a very large commissioned mural, by the artist Fintan McGee, in Melbourne. Next to it we can see part of an illicit non-commissioned artwork by the artist Lush, and over the base of this, lots of tags and throw ups (Figure 3).

Do they all belong to the street? Are they all different versions of streetness? Are the illicit ones more street than the Fintan McGee mural? What’s the relationship between illegality and our sense of art on the street?

In Figure 4 (below), we can see a series of words written by the artist Brad Downey in Berlin.

To some people this might look like nonsense, but if you know Brad Downey’s work, then you would perceive this as part of a body of work in which the artist is interested in problematizing ways that we make meaning, problematizing ideas of tagging, problematizing ideas of the location that we make art in. But the spectator brings so much knowledge to both, that the idea that the artwork has any intrinsic essence to it is rendered quite problematic.

I’m a great fan of the sticker. And I think that the sticker is the most overlooked and ignored form of art on the street. Either as a singular item, or here, in Tokyo, where you get a kind of collage effect on the back of a street sign (Figure 5, above).

It is easy to overlook them in the street, it’s easy not to theorise them. But I would want to argue that thinking about the sticker can teach us things about other kinds of art in the street as well. In Figure 6, we can see an icon tag in Berlin, in a very inaccessible place.

It’s not by any means in a street, or near a street, it’s actually on a trainline – does it have streetness? Is it a street art work? For me, I would think yes, but it is possible to understand how city authorities for example can move to classify this as graffiti and not street art, and so on.

On the ground in Melbourne we can see a very small tag by Lister and some tags by other artists as well (Figure 7).

To me this is a highly interesting example of art on the street – literally on the street that you walk on. It’s easy to walk over it and not notice it. I think Lister’s text is perfectly positioned – the placement of the letters is really harmonious with the surface.

Some people might think that it’s ridiculous to talk about a little tag and a little bit of street infrastructure in the way that I just did. But I would strongly want to assert, why not? Why can’t we think about this surface in the way that the artist thought about it – in positioning the letters, and sizing them and scaling them the way he did?

In Figure 8, we have a wall in Melbourne – more tags on it, on the right-hand panel, and lots of other examples of work along it.

This is a commissioned mural done with everyone’s permission. The tags on the right pay tribute to graffiti writers in Melbourne over the decades. To me this is the least street connected work that I’ve shown. And I would argue that it’s possible that you could say this is nothing to do with the street at all, even though it’s on the street. I wonder whether we actually need new kinds of terminology – civic beautification, community murals, perhaps some new kind of a new cultural heritage if it becomes important to preserve and honour tags – which is a project I would support. Is this the right way to go about it? Is this a version of a new cultural heritage for a new art form? Is this how it should be done?

Encounter II: The Wall

Let’s move to the second encounter. An encounter with two walls, two locations.

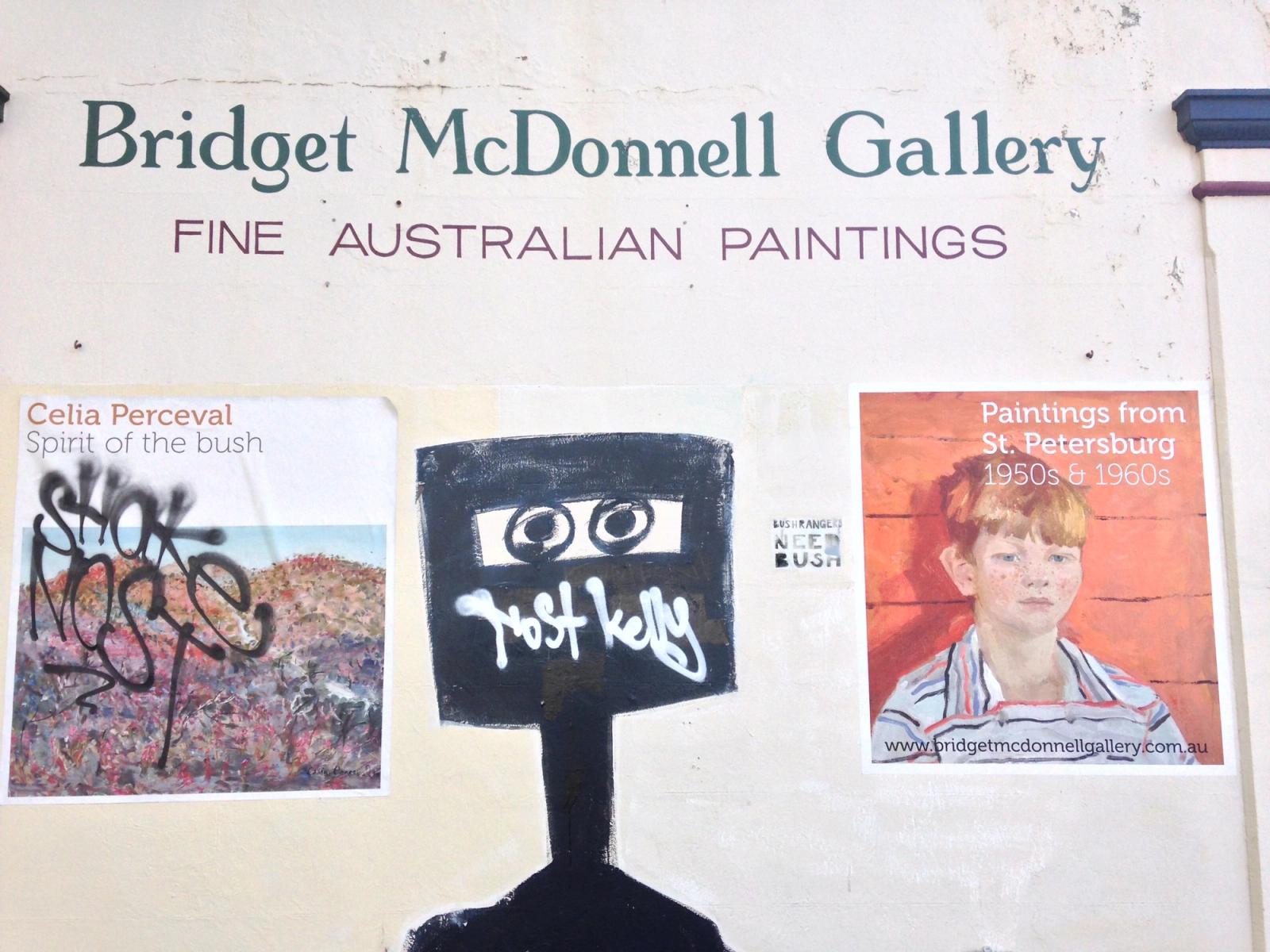

Each day when I walk between my home and my office I pass by this gallery. It’s located on a street corner. These works are on paper, and have been pasted onto it (Figure 9).

And in Figure 10, you can see the other side of the gallery, two more works on paper pasted onto the side of the gallery and one piece that’s been painted directly on it.

These refer to work that has been displayed in the gallery but also the central image refers to an icon of Australian art – Sydney Nolan’s paintings of the Australian bushranger, Ned Kelly. These are hugely significant paintings within contemporary art. What’s interesting to me is that the gallery is using the techniques of street artists in order to advertise fine art. It maintains the paste ups: when they get a little weathered or tattered it takes them down and puts up new ones. And it touches up the Ned Kelly figure every so often. It’s using the street in the way that a street artist would – it thinks about the positioning and so on – but it’s very clearly referenced as fine art and not street art itself.

Around the corner form this building is another place I walk past each day (Figure 11). This is a vacant building, unoccupied – many years ago it was a milk bar, a small corner store – it’s been unoccupied for many years. Artists have put up a great many things on it. Paste ups, tags, large graffiti pieces, political slogans, stickers. It’s been an incredibly mobile surface, and I’ve been documenting it for about four or five years.

I’m interested in these walls because pasting paper and painting directly onto the walls are techniques used by both the gallery and by the artists who come past this site. Every so often the work gets buffed. You can see a range of different things that have been going on, on the wall.

The gallery wall gets tagged as well. All walls get tagged. But this gallery wall has been tagged because the artists and graffiti writers can identify very well that the gallery is using their techniques – it’s pasting up on its own walls and it’s painting directly on its own walls… and so they have come along to join in. Nost was a notorious graffiti writer in Melbourne who tagged very high up in places – every surface that he could over many years, and was in prison last year for several months. So, the fact that he has written ‘Nost Kelly’ on the Ned Kelly figure is drawing a very interesting point of connection between the icon of fine art, the icon of Australian history – the outlaw – and the graffiti writer. In calling himself Nost Kelly he is reconfiguring himself in that vein (Figure 12).

So, here’s what happens when the work gets tagged. The gallery comes out and cleans them up. When the milk bar gets tagged, it also gets buffed. It’s buffed in a really lazy, very typical way – it’s not a complete paintover, it’s an obliteration of what was there. And the buff results in responses from artists, so once a buff is added, it gets repainted by artists, and it gets buffed again, and then more tags get added.

And then one day, in the middle of all this swirl of imagery a small sign appeared (Figure 13).

You can see it here on the central wall. A little blue sign. And it became of interest to me because it’s also placed there illicitly. It was advertising the sponsorship of a school fair by an estate agent. This is common in Melbourne. Estate agents donate their signs, they make a sign for the school fair which can be put up in various places around the city… you are supposed to get permission to do it, but with a derelict milk bar, there was no one to get permission from. So, it says the name of the estate agent, says that it’s a primary school fete. It states the date of the event. The date of the event is long in the past, but this sign stayed on the wall for months, untouched. The buff, when it was carried out, took place around it. There was no attempt to remove it. Something about it had an air of authority. It’s as though the council cleaning crew when they came to paint over it, they would say, “Hmm, this sign has a right to be here”, yet there was no actual utility to the sign anymore. But something in the authority of the idea of sponsorship, of the estate agent, the school, gave it a right to be there that the other illicit works did not have.

In Figure 14, you can see a post-buffed Ned Kelly on the outside of the gallery.

The lettering is still faintly visible underneath it but it’s been painted over by the gallery. The painted outlaw figure of Ned Kelly has more authority to be there than the additions of graffiti writers.

So, I was monitoring these mobile walls, these changing sites, and finding it very interesting that the estate agent sign stayed. It stayed tenaciously to the wall for 18 months. Until last week, when it was gone. Paint had replaced whatever vaguely eroded paint was underneath it, a fresh rectangle of paint sat there, and artists were now adding work around it. I’ve been monitoring this for about 5 years – and I’m continuing to do so – watch this space and see what happens.

Encounter III: The Void

The third encounter is with the void. Here I want to ask – is it possible to imagine a non-image? What happens when illicit images are created in a very particular part of public space? In what is called, by some theorists, a non-space. My interest is in the public transport stop. The areas on and in which we stand when we are waiting for a train, or a tram, or a bus. These might take the form of station platforms, specially built areas, or it might be a smaller slice of space, that’s been set aside on a pavement, or a demarcated area in a roadway. It’s for passengers to wait for trains buses trams and so on. These are excellent examples of what has been called a non-space. Non-spaces lack functions other than suspension and transition. Individuals move through these spaces only in order to get out of them. They are travelling from one place to another, and it takes them through the non-place. They’ve got no desire to spend time within it – these non-places exist just as territory to be crossed, and when they are not crossing through it, they are held in suspension, they are waiting until they are able to cross through them, or exit from them. Public transport stops are non-spaces. The stop exists to enable passengers just to gather in one place until they can board the train, on their route.

The work of Art in Ad Places, Brandalism, Public Ad Campaign, Vermibus, Jordan Seiler, and many others, has become familiar to us in recent years. What they do is often called subvertising. Within the community of subvertisers, working in non-spaces and public transport sites, the Melbourne-based activities of Kyle Magee are distinctive in several ways. He’s evolved a means of altering the advertisements located within these panels which doesn’t rely on having a key or any other means of accessing the advert that’s located within, and which doesn’t aim for speed of subvertising or for the avoidance of arrest. So, in Melbourne, Magee has engaged in a series of interventions that cover adverts.

His actions take place in a kind of struggle over the image. A struggle that involves his rejection of what he says is corporate capitalist advertising, and what he wants is a total worldwide ban on corporate capitalist for profit advertising in public media and public space. He began his actions against advertising in 2005, and he started painting over billboards. After some months, he was arrested, and when he resumed his activities, he maintained the strategy of painting ads but he shifted the location – from full scale billboards to painting over smaller adverts at tram shelters. He reasoned that if he was painting a smaller amount of surface then the damage that could be claimed to be caused by him would be less, therefore the punishment should be less. If you are charged with criminal damage, it’s usually expressed as a financial sum of damage that you’ve caused – if painting a billboard leads to a charge of causing £20K worth of damage, he thought a tram shelter would occasion lower sentences. So, he painted over panels for a lengthy period, but then he switched his mode of intervention again and he decided he would paste paper over the adverts to cover them, again in the belief that this might occasion less ‘damage’ and lead to lesser charges.

Pasting paper didn’t solve the problem of being charged, he has faced many sets of charges arising from papering over tram stops and he has served several prison sentences now. He has had so many convictions that now whenever he is arrested, he goes to prison. One of his favoured spots is at the street intersection where the County Court, Magistrates’ Court and the Supreme Court are located – he doesn’t seek to avoid arrest, and he believes that choosing a site that is next to the courts saves time for everyone.

Figure 15 is an example of a work that’s been painted. You can see that when he was doing this he formed a very neat rectangle where everything that was underneath was obliterated. Once he changed tactic and started papering, then, as I said the idea wasn’t to create another image – but he simply adds the paper until he is satisfied that the advert is obscured. It doesn’t have to be even, it doesn’t have to be a total covering, it simply satisfied his sense that the ad is obscured.

This is one of the main train stations in Melbourne – he chooses very public spaces, he chooses very busy times of the day, he chooses heavily surveilled places. He puts his name and website and mobile phone number on the paper to make it easier for the police to come and to arrest him. When passers-by speak to him, he says he they are welcome to call the police if they wish (Figure 16).

So, what is going on? Magee is not trying to create an alternative image. He is not trying to design something that is an aesthetically pleasing alternative to the advert. He’s not writing culture jamming slogans, he is not removing the advert and replacing it with an artwork. The purpose of what is he is doing is simply to draw attention to the fact that they cover an ad. So, what he is doing is creating a negation, he is creating a nothing, so the spectator does not even have to generate any kind of accurate interpretation of what he is doing – vandalism, damage, culture jamming, subvertising, and so on – instead, the spectator just encounters the result as something that has changed the space and the flow of people in the space, and that demands engagement in the interpretation. So, before any particular emotional or intellectual response is generated, the image seeks the spectator’s engagement as a nothing, as an interruption, or a disruption. So, any meaning in what they see can only be generated through an active engagement or encounter – with the brushstrokes, or with these haphazardly placed sheets of paper. I am interested in these as a non-image, or an image that seeks to be a non-image, an image that prefers a void – its brushstrokes or its pieces of paper represent the idea of a void, and do so in preference to an image in the form of an advertisement (Figure 17).

When I’ve been thinking about Magee’s non-images, I think that this might help us work out what is the art that we see in the streets so often today. I’m not looking for a commissioned wall of tribute tags, or for a preserved wall with a Banksy piece on it, I’m not looking for an encounter with a famous artist who has dropped into town and put up a mural with the consent of the community – I’m interested in an encounter with all of the disruptive possibilities that the street can offer. I am interested in what we mean by a wall, what kinds of things seem to fall short of being an image, because that should make us question our definitions of what an image is. It’s in these non-images by Kyle Magee, the switching swirl of images over time on the milk bar wall, in the tags on the gallery’s posters, in the words that Brad Downey has written on the overpass, on the stickers on the backs of street signs, and Lister’s little tag on the ground. It’s in these images that I want to argue that we can find art as an interruption, as an intervention, and art that is of, on and in the streets.

Alison Young is the Francine V. McNiff Professor of Criminology in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne. Alison is the author of Street Art World (2016), Street Art, Public City (2014), Street/Studio (2010) (with Ghostpatrol, Miso and T. Smits), Judging the Image (2005) and Imagining Crime (1996), as well as numerous articles on the intersections of law, crime, and the image. She is the founder of the Urban Environments Research Network, an interdisciplinary group of academics, artists, activists and architects. She’s also a Research Convenor within the Future Cities Cluster in the Melbourne Sustainable Societies Institute, and is a member of the Research Unit in Public Cultures, an interdisciplinary group of academics, artists, policymakers and urban designers interested in communicative cities, mobility, networked cultures, and public space. Alison is currently researching the relationships between art, culture, crime and urban atmospheres.