Nicolas Whybrow is Professor of Urban Performance Studies in the School of Theatre & Performance and Cultural & Media Policy Studies at the University of Warwick, Coventry, UK. His most recent books are Art and the City, and the edited volume Performing Cities. He is currently writing a book on contemporary art biennials in Europe (for Bloomsbury). Nicolas is the principal investigator in a 3-year UK Arts and Humanities Research Council-funded research project entitled Sensing the City: An Embodied Documentation and Mapping of the Changing Uses and Tempers of Urban Place which commenced in April 2017 and will undertake a series of site-specific studies of urban rhythms, atmospheres, textures, practices and patterns of behaviour.

Thejaswini Jagannath: What was the impetus behind writing Art and the City?

Nicolas Whybrow: In general terms, the impetus was provided by a desire to write about the way art engages and is integrated in increasingly varied ways in urban contexts. That desire arose against a backdrop of a growing urban population on a global scale – the tipping point of a predominantly urban, as against rural (or ‘other’) population famously occurring in 2007 – which made the question of how to live in cities all the more pertinent. Being a theatre and performance studies academic I was particularly interested in the way the triangular relationship between urban environment, people and art was a performative one. In other words, one that was premised on interactivity and movement in space and therefore productive of some form of dynamic.

Far from art being ‘mere aesthetic adornment’ I was keen to make the case for art to be seen as constitutive of the city. In the same way as we accept that architects and planners build cities, so art actively contributes to the construction of the urban, and the citizen is central in that process. In a specific sense I was intrigued by a phrase culled from the space theorist Henri Lefebvre which predicted that the future of art was ‘not artistic’, as he puts it, but urban. It was the paradox of art not being art on the one hand and the promise of art being irrevocably contingent upon the urban that fascinated me. The former points towards an anti-elitist vision of art that is bound up with citizens’ inherent rights to the city, while the latter seemed to me to be reflected in a growing preoccupation with matters urban, visible in the work of artists. So, many artworks, far beyond those specifically sited or taking place in the city as public art or event, appeared to be driven by the question of urban life. I was interested, then, in writing about that which Nicolas Bourriaud had referred to in his book Relational Aesthetics – and in an echo of Lefebvre’s view – as ‘a growing urbanisation of the artistic experiment’ on a global scale.

Why do you think public art is specifically important in today’s cities?

I think I would have to preface my response by stating that I think public art in cities has infinitely widened its scope in recent times to the extent that it is probably more accurate to talk of an expanded field of urban aesthetics. So, a multifarious new aesthetic has emerged that locates itself in, and is contingent upon urban contexts, and that frequently enlists a participatory spectatorship.

This view references, first, Rosalind Krauss’ seminal notion of the expanded field of sculpture as, in essence, an elaboration of the possibilities of the object in space, and, second, more radical, contemporary diversifications of the concept (see, for example, Grubinger and Heiser’s Sculpture Unlimited), taking into account various recent ‘turns’ in art making: site-specific, everyday, social, cultural, relational, participatory, live, digital, performative and so on.

Moreover, the various forms in question span the official (funded, commissioned, institutionally framed etc) and the unofficial: playful interventions by ordinary citizens which might include free running, tagging (graffiti), flash/freeze mobs etc. One of my concerns in Art and the City is to show how there is an implicit dialogue not only between diverse artworks occurring in any one city but also between so-called high and low or official/unofficial forms. The importance of art in cities rests on the way it holds a vital and integrated position. That is, art is thoroughly implicated within the day-to-day workings of urban life and can therefore be said to be as essential as any other amenity available in the city.

At the same time, it possesses aesthetic properties that are particular to it and contribute to its potency, though these take a wide range of forms. Thus, art is indispensable and this is accounted for in part by its capacities to tease out the complexities of modern urban living. This might include drawing attention to the latter’s fragile, often fragmented or dispersed nature and therefore its problems. So, part of the implicit function of art is to initiate and facilitate forms of public critique for the general good of the urban populace.

Can you give some examples of prominent public art which has given significance to their landscape?

Some resonant examples might be the decisive role Christo and Jeanne Claude’s fortnight-long wrapping of the Berlin Reichstag building in 1995 had in focusing the post-Cold War renewal of both urban and national imaginaries after the fall of the Wall in 1989. Or, at a less spectacular but doubtless more controversial level, there is the artist Rachel Whiteread’s Holocaust memorial installation unveiled in 2000 in Vienna city centre’s Judenplatz, which – without particularly setting out to do so – brought to the surface not only a city’s but a nation’s collective denial of any perceived need to come to terms with its implication in a recent national socialist past.

And, at the more ‘unofficial’ end – arguably – of the art spectrum, who would gainsay the effectiveness of the infamous and anonymous Banksy’s contribution to cultivating a spontaneous, responsive form of urban conversation – if not spat – via his witty and provocative throw-up cartoons and statements? Relating most memorably perhaps in the public imagination to various parts of London, his recent interventions have been making provocative incursions on a daily basis into the streets of New York City, to the apparent chagrin of the local hardcore tagging community, which evidently perceives its right to critique its own home turf is being usurped by an interloper (Banksy declared himself to be artist-in-residence in the city for the period of a month in late 2013).

In your book, you mention the works of Lefebvre and other urban theorists. Why is it important to take note of the theory behind art to understand the city?

I’m not sure I entirely understand the question in the way it’s phrased, but first a spatial adjustment: I’m not convinced such theory is ‘behind’ art. If it can be situated anywhere it is perhaps more ‘in and around’, whereby its fluidity, reciprocity (in relation to art) and capacity to evolve is key.

Artists may be influenced by certain theories or may even be consciously testing them through their artworks, but from my perspective as a writer about art and the city, the theories of a Lefebvre provide essential tools with which to interrogate both urban life and art. So, as I explained above, my aim was to see whether his prediction relating to the future of art as an urban-bound phenomenon held up some forty years after he articulated it (his future was my present).

To pursue the point a little further: Lefebvre was an influence on the early thinking and practices of the Situationist International whose instinctive position – as a radical political movement – on art, was to dismiss it (they were referring principally to the bourgeois art world) and to align it with the general spectacularisation or banal commodification of urban life. In fact, the Situationists gave birth to a whole host of highly radical creative practices that have acquired a particular currency with artists in recent times but which emerged and evolved as a result of their particular socio-economic and cultural critique of urban life and a desire to give validity to everyday practices. “I would feel out of place were I not living in the city. In that generic sense, I need it.”

What is your relationship with the urban realm?

I’ve always lived in cities, which is not an unusual thing in itself, of course. But I’ve always felt myself to be an urban dweller. In other words, I would feel out of place were I not living in the city. In that generic sense I need it. Having said that, no one city is like another – which is part of the appeal of having a creative and research-based interest in urbanity – and I have lived in ones as varied as Barcelona, Ankara, Belgrade, Edinburgh and West Berlin (globally speaking that actually represents quite a limited geographical realm, however).

My interest in writing about cities evolved from a specific book project entitled Street Scenes (2005) in which I attempted to ‘find Brecht’ in Berlin some ten years after the Wall came down, using a Benjaminian walking-and-writing methodology. In other words, I spent a few months in the rapidly-changing new Berlin of the early 21st century to see whether the radical ideas of those ‘Berlin natives’ Benjamin and Brecht still had currency in my attempt to grasp what was going on in the city.

How do you think art has shaped or changed the cities of today compared to previous decades?

I’m not an urban historian, so I would find it difficult to make such temporal comparisons and pronounce on that with any conviction or profundity. It’s also difficult to generalize – globalisation or no – about the ‘cities of today’ since local circumstances are subject to all kinds of complex cultural and political factors, so it’s a very varied picture. What I will say is that the idea of art figuring in – that is, shaping or changing – the urban realm is not by any means new. So, ‘previous decades’ aside, historically speaking one need only mention the culturally rich cities of (ancient) Athens, Rome and Constantinople/Byzantium (Istanbul) to illustrate the point. By the same token, I’m sure there are endless instances of cities in history where art has played a minimal role for whatever reason (repressive regimes, poverty, war etc) or has gone from playing a significant role to becoming marginalized owing to changing fortunes. And that would apply in the present day as well.

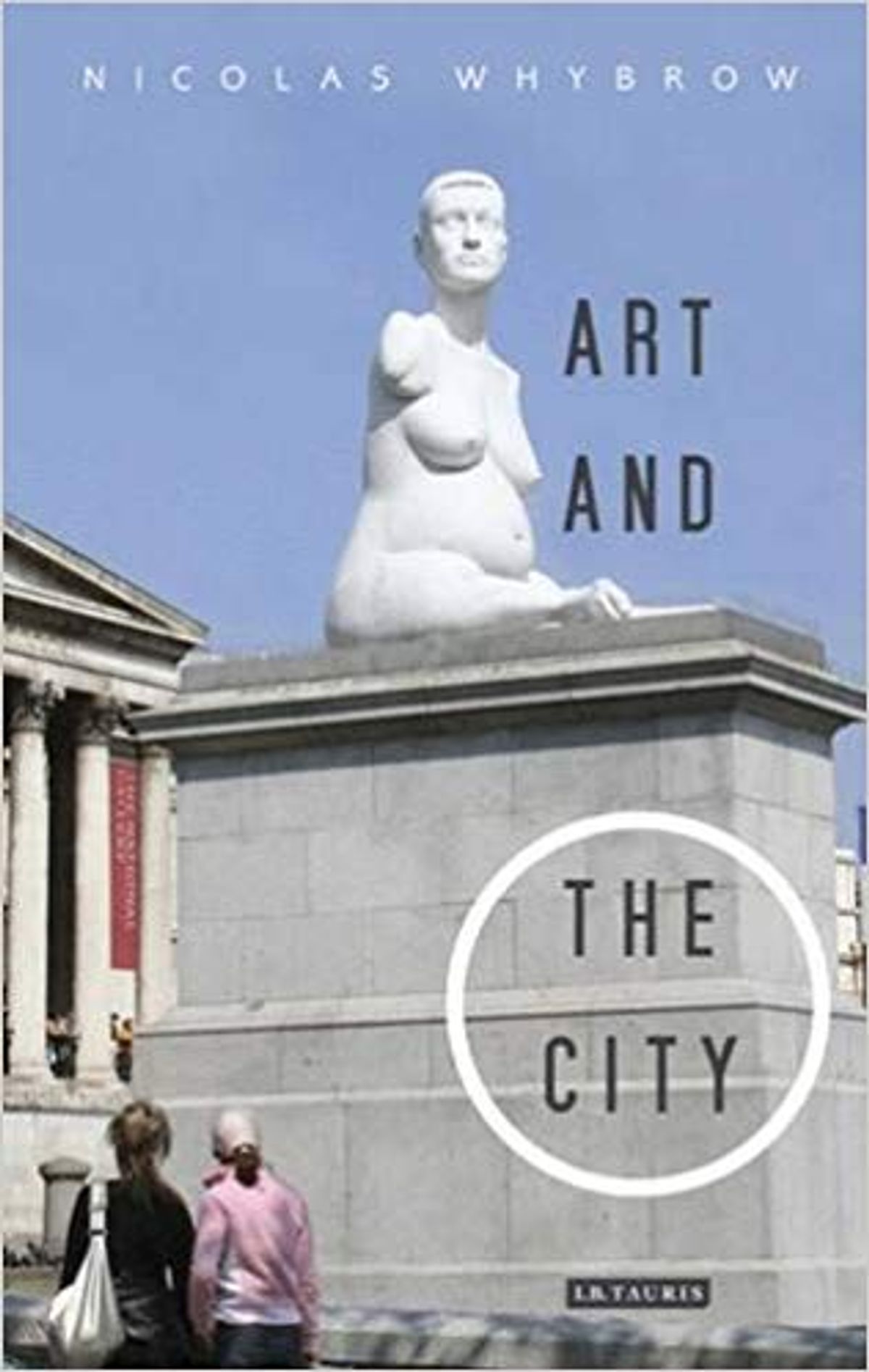

To return to Lefebvre, what he bewailed was the fact that art had been taken out of the hands of citizens, where it had once been (see, precisely, Athens), and had become institutionalized – that is, literally ‘housed’ or stuck in buildings (theatres, for example) when it had once been in the public realm of ‘the street’. For him, then, the future of art resided in the promise of a return to the space of the city, a move that was, as he puts it, ‘fundamentally linked to play, [to] subordinating to play rather than to subordinate play to the “seriousness” of culturalism’. In other words, he was asserting the right of the urban dweller to a form of participatory citizenship through ‘spontaneous theatre’. And I think there are many contemporary instances of this essential idea of democratisation being embraced and being decisive in shaping the way cities are perceived, from the impromptu Qash mob to something like Gormley’s durational, living sculpture One and Other on the fourth plinth at London’s Trafalgar Square in 2009.

Do you believe art has gained more prominence in today’s cities?

My sense is that there is a greater proliferation of creative forms that either take urban living as their cue or that seek to engage directly with the urban realm and this is bound up with the changing perception of what art is. So, this is where the ‘expanded field’ comes into play. There are many more kinds of art now and public/spectator participation as a prerequisite or integrated part of the artwork is also at a premium in contemporary practices, as a result of which many more people are involved in creative activity.

Art is more accessible to the public these days with more public art being constructed and showcased for the public. This leads to more interaction between the artwork and the public. Why is it important to ensure art is accessible to the public rather than just being tied to museums or art galleries?

This goes back to Lefebvre’s point about the ‘seriousness of culturalism’ and participatory democracies. Museums and galleries themselves have opened up and become popular to a far greater extent (see Tate Modern, for instance, with its staggering and unforeseen annual attendance average of seven million), but they still have a tendency to be seen as the preserve of an educated and/or privileged strata of society. So, if you want to reach the broader public and allow it to reap the all round critical and inspirational benefit of art, one way is to leave the building.

When writing your book you mention that you had the opportunity to travel. Where did you travel and what did your travels reveal about art in the city?

I didn’t really travel very far for the purposes of researching the book! It has a very strong focus on London and that is mainly because it is on my doorstep (although I don’t actually live there). But it also has a high degree of creative activity, so it is very appealing and rich in what it has to offer, and there’s plenty to write about. Cities for which I left the UK were all German speaking as it happens: Vienna, Berlin and Muenster (where the decennial Sculpture Projects takes place).

But the point of the book was more to write about a variety of urban artworks rather than a variety of global cities. To do the latter one has to have time and money and that’s not always easy to engineer if you have formal responsibilities as a full-time academic. Once the book had appeared I found myself being invited to all kinds of cities to give keynotes or participate in exploratory discussions about art and the city (Belgrade, Turku, Copenhagen, Cologne, Winnipeg, Melbourne, to name a few), so it evidently had certain resonances in a range of diverse places.

As far as revelations about art in the city go, that’s a bit difficult to sum up in this limited space, but in a general sense I found that sited art serves as an incredibly rich means of navigating the city. That is, of getting your bearings and developing a critical sense of place. I was also fascinated by the way that artworks that have nothing to do with one another in their conception can begin to ‘converse’, or, more accurately perhaps, can be made to converse with one another ‘across town’ as it were, thus producing a form of curated portrait or choreography of a city. So, I found ‘conversations’ in London, for instance, between works by Anthony Gormley, Mark Quinn, freeze mobs, Martin Creed and free running. Curating these conversations amounts to a form of practice (as research) in its own right.

Your book touches on urban geography, anthropology, architecture and art. This makes it very interdisciplinary. What category would you describe your book to be in?

Well, like you say, it’s interdisciplinary, so I’m reluctant to pin it down to one category. However, there’s a strong performance bias, but then performance (studies) is, arguably, an ‘inter-discipline’ in itself because of the way it draws from or figures in a range of fields. There’s also a strong auto-ethnographic strain inasmuch as I put myself and my encounters with artworks and cities at the heart of the writing, sometimes making use of a walking-as-fieldwork methodology. The final factor worth mentioning is that it’s also a book about writing itself: how to write about art and the city. So, each of the chapters in Part 2 is an excursion into writing or a form of ‘site-writing’ or ‘critical spatial practice’, as Jane Rendell calls it.

What guidance would you give young researchers interested in researching art within the realm of cities? How can this topic gain more prominence?

I think there is already a lot of interest in cities and art, as I have argued, and from a range of disciplinary perspectives. So, you have leading cultural geographers such as Nigel Thrift and Steve Pile writing about art and performance in cities, urban designers such as Quentin Stevens looking at unorthodox uses of art in cities, political scientists such as Esther Leslie writing about art practices derived from an engagement with urban waste and so on. The list really is long. So, the topic already has prominence. The global explosion of art biennales and large-scale, site-based performance festivals such as Metropolis in Copenhagen or Infecting the City in Cape Town has also contributed to a form of high visibility in recent years because of the way such events tend to make use of the whole space of the city and therefore suck in all kinds of local constituencies (while simultaneously labouring against accusations of art world elitism and motives of a corporate-consumerist nature).

Aside from that there are the various informal, unofficial and everyday incursions that I have already mentioned (from the individual tag down a residential back alley to the silent mobile clubbing intervention on the main concourse of a metropolitan train station), which arguably arise in some instances as a reaction to increasing ‘screen time’ – a desire to escape the virtual-digital realm and sense the physical presence or materiality of things and bodies in space.

So, as far as advice to young researchers goes, in one relatively superficial sense I don’t think more needs to be said than ‘get out there and keep your eyes peeled!’ What that implies is inhabiting the space of the city in order to observe and gauge what is going on, so there is a strong fieldwork factor in this form of research.

Art and the City is available from I.B. Taurus, London. https://www.ibtauris.com/

Thejaswini Jagannath recently graduated from Master of Planning from the University of Otago. She has authored for numerous online websites and has published widely on city planning issues. She has written two theses on public art and is passionate about city planning.