Pietro, your curatorial practice diverges from standard curatorial practice, in that it seems very much ground up, rather than top-down. You pair getting up with photography as a means to translate the values of the scene to the art world.

Pietro Rivasi:I am not a professional curator. l never studied art. I just started painting graffiti in the 90s, and then I started organising the first festivals here in Italy, mixing up graffiti with some stuff that we have come to call street art. The first festival we organised was in 2002, and we also curated small indoor shows with the same artists. From the beginning, the most important point for selecting artists to take part was to be up, and to be respected by the scene.

When I grew older I started to look more to other galleries who were starting to show street art. Something I never really understood was why they were showing people who never got up in the street. And when a lot of very good illustrators started to paint murals and sell canvases as if they were street artists, I was like, “hey this doesn’t reference anything within the real graffiti and street art world.” When I do shows, I try and point out that if you want to represent the street culture, then you must be respected within that culture, and if you are not, if you don’t have this background, you should stick to some other field.

For me graffiti is definitely an artform. The strength of graffiti as a communication system comes from it being in the street. That’s why it got attention in the 70s. It was strong because it was on the trains. If kids were just writing on paper, at home, nobody would have noticed them. So, the strong part was the work being in the street, and being political – really radical – against public and private property. But when graffiti writers started to do shows, they started to do shows with canvases. And all the other aspects of their work got lost.

My way to try to reconnect these various aspects was to curate shows using photographs of illegally painted pieces – and to try to get gallery visitors to think: “Why should I consider a piece painted without permission in the street as vandalism, but if I see the same picture in the museum, why should I consider it as an artwork?” – “Because there is a curator who tells me, this is art?” And that’s why, in 1984, we included artists who were painting stuff illegally in the streets, in the same city, at the same time. We had the photographs of their work inside the gallery and the actual pieces still up in the streets, so people could, in theory, see the piece inside the gallery and outside in the street.

So, 1984 blurred the boundaries between the inside and the outside of the museum?

The starting point for me was that we have graffiti writers and street artists that want to reach a different audience. And some of them are really good at stuff that really works well in the street, but they are not as good at doing canvases. If we have writers and street artists that want to go into galleries, is there a way to have their work exposed so that they feel that it has not been completely decontextualized in order to sell something? Can we do it in a way that is more like the original practice?

If they want to enter the galleries, in my view, we must find some other solution. And the solution we present in this book is the most respectful of the original practice as possible. If you use the documentation of the practice as the artwork – a photograph, or a video, or a sketch – you are doing something that performance artists and land artists used to do in the 1970s, so it’s really nothing new. It’s something that the artworld has already accepted and exploited. So why can’t we do the same for urban art? That also gives the artist the possibility to continue painting in the streets, and at the same time to get some money and recognition for their art staying in the streets – as an alternative to studio-based practice.

How did the museum react to the inclusion of illegal works in the show?

The museum really didn’t know in advance exactly what the show would feature, but they reacted really well to the final result. Of course, I submitted a proposal for the whole show, some months before, so they knew I wanted to work on the concept of vandalism as art. So, they were aware of the focus of the show, and actually they understood that the most controversial part was probably the most interesting.

In your book, you talk about the museum acquiring a work painted without permission WITHOUT seeking to remove it from its original location in the streets. To your knowledge, is this the first time this has occurred?

This acquisition came about because the museum recognised that this was actually the most interesting part of the work. If it was a street-based work by Banksy or BLU they would probably have protected it without asking anything, but the controversy comes about because the artist who painted this was really not that famous – within the art world at least. That was the most controversial part – to have a public institution recognise vandalism as art without economic values telling them that they should recognise it.

I discussed this with Robert Kaltenhäuser and also the curator-artist Jens Besser – both were involved in the development of the ideas behind this acquisition. We think that this is the first example of this kind. The idea behind the museum’s acquisition was to leave the work in the street to fade away – and whatever happens to the work happens. The idea is that the institution recognises it, and acquires the photographs of the piece. So, when the piece disappears, the institution still has the photographs, and the photographs will then be the artwork. It’s the only thing that testifies that the artwork ever existed.

In terms of the illegal work itself, is there anything in situ that marks it as having been acquired by the museum?

We designed a plate and we dealt with the city’s cultural authorities and officials. We wanted to put the plate in the street, to signal to the people that this is a real artwork that the institution acquired, but we are in Italy, and there are plenty of bureaucrats in the city council. We are still waiting for definitive permission.

Maybe once the work has gone, you’ll get the plate?

That would not be a problem – it would work, even like this! The plate comes with a QR code, so you can take a picture and see the painting even if it has disappeared.

In the museum, where the photograph was displayed, was there a map of the work and its location, so people could go and find it?

No, but the title of the artwork was the name of the building – and everyone in the city knows this building, so there was no map. We also did some guided tours as part of the show.

Andrea, let’s talk about your section of the book. Can we talk some more about what the “appreciative practice” in graffiti involves?

Andrea Baldini:I borrowed the concept of appreciative practice from the work of Dom Lopes, who is also a philosopher of art. The concept comes from his work on the definition of art. The idea is that we don’t need to seek a general definition of art, but we can define locally, different forms of art, or forms of expression, as appreciative practices. We can understand the practice by which you appreciate a set of objects by relating those objects to other elements of the practice – or to other objects that are similar. Objects can be the focus of different appreciative practices, which might share some borders. When you look at objects of design, you can look at an object of design and appreciate it as, for instance a coffee machine, or as an example of design. These might involve slightly different appreciative practices, because they put emphasis on different features. So, when you relate it to graffiti, then what happens is that you appreciate graffiti by looking at other examples of graffiti.

You argue that, “the core of the appreciative practice in graffiti relies on engaging with reproductions rather with originals; and that (ii) reproductions do not lack any of the salient properties that are relevant to the appreciation of graffiti.”

In general, there are two sources for this claim. One is based on discussion and the second on observation. This claim comes primarily from my observations on the life of graffiti writers, when I was hanging out with some writers in L’Aquila in Italy. It was their reunion after 10 years. They were preparing an historic show where they were going to put together all their pictures from 10-15 years of writing.

I remember them showing each other their photographs, and I remember this sense of community, this sense of enjoyment – I hadn’t experienced this before. It felt like something very authentic to their practice, and something very true to what they produced, because of course most of them hadn’t seen all of the pieces the others had done. And this reminds me of FRA 32’s reaction to 1984. When I talked to FRA 32 about the exhibition, he was very sceptical about the project, but after he had seen the installation of photographs dedicated to his work, his comment was that “it felt so authentic.”

So, it’s not even just the sharing of photos online or on Instagram today – it’s something that has a long trajectory within graffiti, and it seems to me to be the natural way in which writers experience graffiti – not all of the time – but a bulk of this experience is through photographs, or so called reproductions, rather than through the originals.

That’s definitely part of that subcultural practice. Were blackbooks something you considered – you know, writers’ documentation of planned works, or works in process?

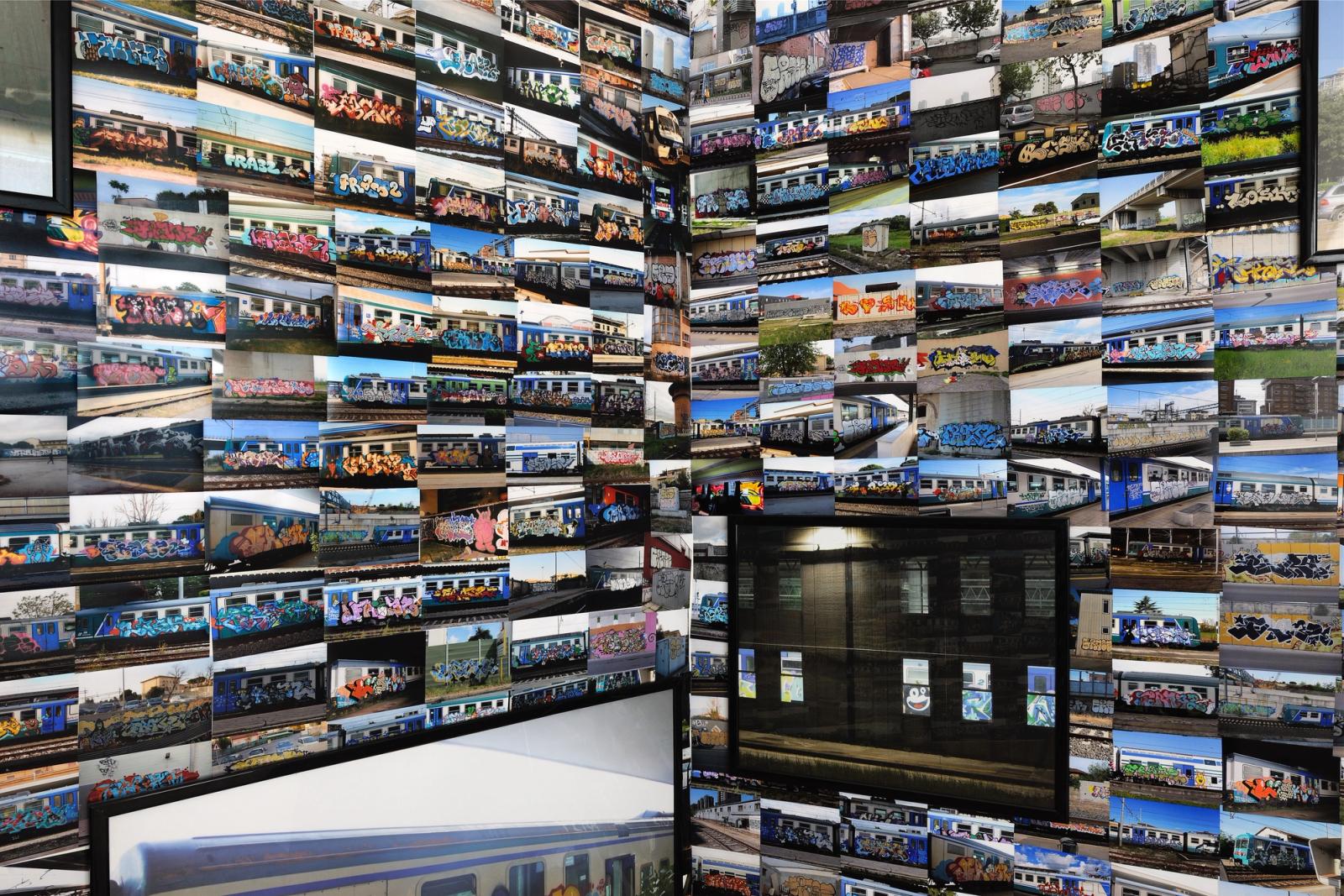

Pietro Rivasi: Actually, we named our installation of more than 1000 pictures:Blackbook. The idea was to transform the concept of the blackbook into an art installation for the white cube. In the show we had three different installations, that were each named after something specific to graffiti culture: Blackbook, The Buff and The Writers’ Bench. Blackbook was this huge photo installation that was meant for the people to enter and feel the foolishness of the writer who goes out every day to paint their name without giving a fuck about the consequences. The idea was to be overwhelmed by the ego and the recklessness of being a graffiti writer. For The Buff, we used video screens. The video was of a guy buffing the same piece, over and over and over again – to give the spectator the impression that the act of destroying art always involves the same gesture, always the same result. For the Writers’ Bench, we had a slide show, that was on constantly over the lifespan of the show. Every picture was a panel painted during the show. We had fresh pictures every week. It was meant to represent the writer’s bench of the 2000s – where you experience the trains, not on the tracks, but on the internet – where the flux of images is always changing.

Andrea, I can see that your claim that the appreciation of graffiti occurs through reproductions clearly relates to 1984’s photographic installations, which seem designed to evoke writers’ own practices of appreciation.

But still, the appreciation of graffiti in its subcultural sense is arguably more hands-on than a mainstream model of the passive appreciation of art in museum space would allow. Does the appreciation of graffiti involve a more participatory process?

Andrea Baldini: Yes, graffiti and street art are forms of spontaneous artistic creation within the public domain, in that they generate or create or engender some kind of response within the public. The public is actually constitutive of the work, rather than just involving a passive response or some kind of contemplation. This kind of appreciation becomes a form of active and creative reception.

Even down to maybe making marks on the wall in response? Which of course, you could not (usually) do in museum space.

Definitely. But I think again there are many different artistic practices. You also can find this kind of interactive model in public art, and in participatory art. I don’t think that there is anything unique about this kind of participatory model. Yet there are peculiarities about the ways in which we – or writers, or even the general public – react to graffiti or street art.

The museum is a public space. Of course, you can allow for certain kinds of responses, but it creates a certain disposition to react. This is different to how you react in the street but the strength of Pietro’s work is the idea of building a continuity between the street and the museum, so that what happens in the museum is not a transformation of the practice, but rather an evolution. What you find in 1984 is something that adds up to what you might find outside but it doesn’t want to substitute – it wants to extend the possibilities for these forms of creative communication.

I’m curious about your use of the experience of viewing photographs of Dondi’s work as an example to ground your claim that, “reproductions do not lack any of the salient properties that are relevant to the appreciation of graffiti.”

The late Dondi now has the status of a founding father – but his work is now arguably inseparable from the photography of Martha Cooper, and the canonical status of ‘Subway Art.’ How well does a legendary example like Dondi fit with the lesser-known artists’ work presented in 1984?

I think that there are two issues here. One is the question of whether photographs can convey all the essential properties that are necessary for the appreciation of graffiti and the other is whether these forms of reproduction (photographs and videos) can acquire the status of art per se.

To some extent I don’t see these questions as essentially related. I never met a writer who said, “I never seen a piece by Dondi” “I don’t know his style” actually they tend to say exactly the opposite.

But is this not, in part, as proof of subcultural membership?

They study the style, so yes of course, but then things get more complicated. Dondi has become an historical figure, so there are layers of value – historical value, and what you consider of value in graffiti – its subversiveness, style, getting up, all the things that one can attach to these works. So, in general of course, one might say that Martha Cooper’s photographs are works of art per se. For instance, Aurelio Amendola is a photographer of Michelangelo’s sculptures. It’s very difficult to say that Aurelio’s photographs are pictures of just the artworks of Michelangelo, because to some extent they are also works of art in their own right.

So, it seems to me that this can happen all the time. There might be better or worse photographs, but it’s like there are wars of better or worse graffiti. Sometimes the photograph is not that good – why should you add a layer of significance to what you’re looking at?

A lot of writers consider that actually part of what they do involves the act of taking a picture. In 1984, there is a photograph of the piece by Zelle Asphaltkultur – the whole train with the explosion. That is a heroic kind of shot. I think that perhaps it was more difficult to get the shot than it was to make the piece.

The recent discovery of a long lost Dondi tag in Manhattan had the aura of an original relic being uncovered. Does that demonstrate that the aura of an original may have an impact that perhaps a reproduction does not?

I am always very sceptical about this idea of the aura. I find it very scary!

I think that what we can see are different layers of the same object. So, we look at the object from different perspectives that are not mutually exclusive. Something that doesn’t have an historical value lacks some of the properties that we see in something that has historical value. Which seems to be what happens with Dondi’s work and the work of Martha Cooper.

But it also seems to me absolutely reasonable to say that Martha Cooper’s photographs are artworks per se and this might not be the case for a lot of what we have seen in 1984. Of course, these are not historicised pieces, so we look at them in slightly different ways. But while there might be different varieties of ways in which we approach these photographs, I think they are compatible, even when there are additional layers.

UN(AUTHORIZED)//COMMISSIONED is available from Whole Train Press, Rome. https://www.wholetrain.eu/

Pietro Rivasi started painting graffiti in the mid 90s. He graduated in pharmaceutic biotechnology, and in 2002 started organizing graffiti and street art related events (Icone, Quadricromie) and collaborating with some of the most influential magazines in the field (Garage Magazine, Graff Zoo). From 2005, he co-curated public architecture and art library “Luigi Poletti’s” collections of urban arts books; and from 2009 he started regular curatorial activity (Spazio Avia Pervia, D406) mostly with artists coming from a “urban” background and organized talks and conferences. In 2015, he participated as a curator in the exhibition, “The bridges of graffiti”, an event coordinated in parallel with the 56th Venice Biennale. In 2016, Rivasi curated “1984. Evoluzione e rigenerazione del writing” at Galleria Civica di Modena. In 2018 he started a new collaboration with Whole Train Press and Vicolo Folletto Art Factories, a contemporary art gallery based in Reggio Emilia. He lives and works in Modena Italy.

Andrea Baldini is Associate Professor of Art Theory and Aesthetics at the School of Arts of Nanjing University, China. His research focuses on theoretical issues emerging from street art’s institutionalization, with particular reference to this urban practice’s relationship with the law and the museum. His monograph “I Fought the Law and the Law Swanned: Street Art and the Law” is forthcoming for Brill Research Perspectives in Art and Law (Brill, 2018). An essay exploring the ethical dimension of an extension of copyright and moral rights to street art will appear in Enrico Bonadio (ed.), Copyright in Street Art and Graffiti: A Country-by-Country Legal Analysis (CUP, 2019). Baldini’s curatorial work focuses on issues emerging in cross-cultural contexts of artistic and aesthetic appreciation. In 2019, his exhibition Images and Words, on the relationship between graffiti and Chinese calligraphy and landscape painting, is scheduled to appear in museums across China.

UN(AUTHORIZED)//COMMISSIONED is a companion to the exhibition, “1984: Evoluzione e rigenerazione del writing” at Palazzina dei Giardini, Galleria Civica di Modena.