This essay is based on Adrian Burnham’s recent talks on The Visual Activism of Dr. D at Nuart Plus, Aberdeen, and Art on the Streets II: Art as Intervention, London. All photographs, unless otherwise stated, ©Adrian Burnham.

Subvertising, ad-busting, culture jamming, billboard détournements… Call it what you will, hijacking or doctoring corporate advertising and/or co-opting official signage in the urban environment continues to be a favoured tactic of socio-politically motivated artists and visual activists. While it’s debatable whether flyposted oppositional art or visual activism has any direct effect in bringing about sociopolitical change, what it can do at its best is feed into the public’s disposition. Through strong imagery, cogent or quizzical text, humour, relatively speedy production and distribution, via its capacity to occupy anomalous spaces in the urban environment. and through an imaginative, enacted engagement with matters of concern, it can generate social media interest and help inform, even propel, opinion.

For Art on the Streets II at the ICA, London and Nuart Plus Aberdeen (2018) I talked about various aspects of flyposted street interventions by focussing on works by Dr. D. a visual activist from London, England, whose efforts ‘doctoring’ everything from big brand billboards to political posters have earned him a degree of recognition that spans the urban interventionist spectrum. The more militant, anti-capitalist wing admires Dr D’s fearless excoriation of right wing public figures and his decades’ long persistance. While the more popular street art audience, casual urban spotters, delight in his pared down wit and audacity.

I kicked off my survey of Dr D’s work with a seemingly forthright piece of his that had stencilled in emphatic, crudely kerned, white capital lettering the phrase ‘We have a dream and you’re not in it!’ (Figure 1).

That’s put passersby firmly in their alienated place then. But there’s more. In the photograph I showed it seems at first – still-fresh wet glue stain framing the work – an arbitrary one-liner. A withering remark randomly slapped on half a sheet of ply leaning against a roadside barrier. I thought just to have succeeded in intervening in this corporately saturated, civically micro-managed space is something of a coup as to seeding alternative voices in the midst of, and at the same time commenting on, consumer culture.

Then in the background you catch the name of the shop the poster is pasted in front of: Mirage electronic cigarettes. Now, ‘We have a dream...’ isn’t just a general general jibe in an amorphous urban context. Its placement uses a feature of its immediate surroundings to open up, to expand its pertinence. Who’s the ‘We’ referring to? Is Dr. D casting the whole urban spectacle as ephemeral or unreal as a mirage? Something we shouldn’t trust?

And reading the work is further layered when we notice ‘We have a dream...’ is printed on a vivid, deep pink flock wall paper. A material so associated with the interiors of old pubs, Indian restuarants, great aunt’s parlours, etc., that it positively reeks of snug, la-di-da indoorsness. Only now it’s outdoors. So we have not only a text that is disaffecting, a location that offers dialogical opportunities, but also a sense of displacement embodied in the materials used to make it.

The relation between Dr D.’s work and its particular placement is on occasion more obviously pointed. He was also in the Granite City with Nuart but while I shuffled bits of paper, Dr. D got to work round the town and surrounds of Aberdeen. The city was once infamous for having more ‘No Ball Games’ signs up that anywhere else in the UK. It’s also a near neighbour to Trump’s golf links. Dr. D affixed to road signage directing traffic to the abominably coiffed POTUS’s pitch n putt, a sign work that read, No Bald Games (Figure 2). Right under the noses of Trump employees it probably didn’t last long, but to a degree the act of putting it up at all, commiting principled civil disobedience, is very much a part of Dr. D’s practice.

Similarly apposite in terms of placement, but hopefully much longer lasting, were two adjacent 10ft high hoardings at Nuart Aberdeen. Though the erection of the works was sanctioned this time, installed as they were directly above the entrance and exit barriers to a shopping complex, the giant iteration of ‘We have a dream...’ proved a sharper, more direct barb at retail therapy and its pretensions to be a coping mechanism. The adjacent work was an image of a monumental Coca Cola can that on closer inspection was actually labelled Cocaine with bold black text underneath that read, Buy the world a God. It was sited both on, and directly opposite, the first floor windows of church owned property. Whoops.

Over a period spanning almost 20 years, Dr. D’s output has taken numerous forms, some of which I’ll elaborate on, but first a whistle-stop tour of a few of his favoured subjects: (i) His HMP London (and elsewhere) series of posters in various formats critiques surveillance culture (Figure 3).

(ii) Rupert Murdoch’s face with the words What A Jeremy Hunt ‘stickered’ over his mouth is one amongst many Dr. D works that challenge abuses of power. (iii) A billboard détournement portraying David Cameron – Conservative Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016 – as a ‘Pirate of the Coalition’ takes aim at one of the buccaneers of Tory policy being geared towards austerity: incompetent, short-sighted and self-serving governance is a subject Dr. D returns to time and time again (Figure 4).

There’s a sense that paste-ups and other DIY interventions are media open to ‘anybody’. And if this isn’t altogether true there is at least an argument that flyposting can access spaces usually dominated by the corporate clients of outdoor advertising companies like J.C. Decaux, Primesight and Clear Channel.

Another recurring feature of Dr. D’s practice are his various interventions that represent and enact participation – works that in quite practical terms invite/promote involvement and public dialogue. These can take the form of ludicrously direct, spontaneous ad takeovers. For example, removing existing panel ads on London Underground trains, turning them over and using that blank canvas to make a work before reinserting it back into its original frame. Dr. D’s Flip the Script takes this approach (Figure 5). A ballpoint pen simply Blu-Tacked to the work, the cheeky ‘woz-ere’ type comment: Look Mum NO Ads and another scribbled reassurance confirming that mistakes are welcome. This, again, is deceptively simple. As well as the literal invitation for alternative voices to contribute to, and contradict the corporate wraparound, its ad hoc form both mocks and interrupts the often too slick surfaces of our urban environment.

In the same vein, but a more sophisticated takeover – involving a selection of marker pens in a tin – sees Dr. D replacing large six sheet bus stop ads with his ambiguous Who Asked You? intervention. It’s double-edged because the phrase first reads as a combative put down, a rebuke that’s usually intended to shut someone up. At the same time, it emerges as a reminder that the public are invariably not asked for their opinions on subjects that affect their lives.

While I’m principally concerned here with Dr. D’s paper-based works on all sorts of spaces, his practice is much broader and includes organizing events, 3D interventions in the streets, and taking over incongruous venues – his 2009 Brainwash installation in a Bethnal Green launderette being a good example. There have also been floating protests on canals: waterborne support for the NHS, anti-privatisation of public services, etc. And while the issues raised might be seen as standard and shared by many a left-leaning communitarian conscience it is Dr. D’s methods, as much as the messages, that mark him out as more effective in terms of prominence and provocation. In Extrastatecraft (2014) Keller Easterling’s concern was to unearth and explore ways that publics might better understand and counter the power of global infrastructure. Her proposed use of ‘less heroic’ techniques in support of radical reform proffer a range of tactics that accord with Dr. D.’s thinking and practice:

Techniques that are less heroic, less automatically oppositional, more effective, and sneakier – techniques like gossip, rumor, gift-giving, compliance, mimicry, comedy, remote control, meaninglessness, misdirection, distraction, hacking, or entrepreneurialism (Easterling, 2014:.213).

Transgressing boundaries can reveal hidden rules. One could cite the precedents of the carnivalesque ‘telling truth to power’, vaudevillian comedy, Dada gestures in art, but all of these, in a “it’s only a bunch of pucks/entertainers /artists” sense, operated in ‘sanctioned’ arenas. Dr. D’s contributions to the urban environment are rarely sanctioned and it’s this that contributes significantly to their traction and incisiveness (Figure 6).

Working on the fly and often employing low-tech media affords opportunities to react to events quickly. Shortly after Charles Saatchi was photographed violently squeezing his then wife Nigella Lawson’s throat, Dr. D’s large paste-up of Saatchi’s face with the words ‘Charlie screws you up’ appeared on a London street (Figure 7). Saatchi is an ex advertising baron and notoriously bullish art collector whose 1992 Young British Artists show spawned a movement – the YBAs – which included now famous artists such as Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst and Sara Lucas. Lawson is a journalist and one of the world’s most recognisable TV chefs.

The ‘Charlie screws you up’ work is a prime example of DIY interventions on the urban environment affording an effective platform for disapproval. Often a starting point for Dr. D’s interventions is to ask the very straightforward question “What’s the problem?” The problem addressed in the work featuring Saatchi was an occasion of domestic violence in a public place: a bully abusing their power. Saatchi and Lawson were divorced shortly afterwards.

Piggybacking recognizable ‘brands’ is another key characteristic of Dr. D’s practice. Producing variations of the classic Evening Standard newspaper poster has been a favoured tactic for Dr. D. The artists Gilbert & George – who in a 2012 newspaper interview referred to Boris Johnson as “a wonderful modern person” – have also used Evening Standard posters in their work.

One significant difference between what the famous artist duo get up to and Dr. D’s approach is that while Gilbert & George extract ‘realism’ from the street and elevate it into a high art, elitist commodity, Dr. D reproduces this form, associated with knee-jerk shock or tacky, titillating banalities and employs it to address pressing social and political concerns albeit with his trademark mordant, somewhat surreal, wit.

Dr. D’s Evening Standard poster work that reads ‘Jeremy Corbyn Ate My Hamster’ makes reference to the veteran Labour leftwinger whose election in 2015 to become Leader of the Official Opposition was one of the biggest upsets in British political history (Figure 8). It also invokes an apparently trivial tabloid headline about a comedian ‘Freddie Starr Ate My Hamster’ from 1986, and succintly demonstrates how mainstream media frame and demonise political developments and individuals who challenge the interests of rich and powerful establishment figures. When you learn it was the notorious publicist Max Clifford who encouraged The Sun newspaper to run the original Freddie Starr story even though he knew it wasn’t true, the Dr. D work becomes a critique of underhand, profit driven media misinformation and the cynical manipulation of publics.

Another intervention that on the face of it seems crudely didactic, but rewards further consideration, is Dr. D’s two billboards, one above the other, that read The Sterile State of Hackney and East End Bloc (Figure 9). Though ‘unpolished’ in some respects: limited palette, simple design and stencil-type rendering, this is far from a tag-and-run operation.

The Sterile State of Hackney and East End Bloc works appeared throughout said borough and more generally around East London. You might think the Marxist-Leninist red star and sparse block-capital lettering, the scale and God-like vantage point – certainly of higher billboards – all indicate a somewhat dictatorial declaration. Pasted up, however, during the death throes of New Labour, one can read the appearance of the red star motif as a cheeky dig at Blair and co.’s neoliberal dilution of core socialist values.

Choosing to ‘stamp’ the city with enigmatic ‘appeals to question’ rather than – what they may first appear as – dictatorial sloganeering suggests an instinctive knowledge of the ‘slipperiness’ of texts on Dr. D’s part. The viewer is not quite told what to think but pointedly invited to wonder what the ‘Sterile State’ is referring to. Is it the then notoriously incompetent management of funds, schools and services by Hackney Borough Council? And what does ‘Bloc’ mean? That venal scramble by an ‘alliance’ of East London boroughs to carve up and scoff from the pre-2012 OIympic trough?

These stark messages were seeking to unsettle, affect and contribute to tweaking the disposition of publics. Some passersby might dismiss the works as a red star diatribe, but then be confused because New Labour were supposed to have ousted the loony left years beforehand. Others, a good proportion of whom were fiercely suspicious of the whole Olympic smoke and mirrors ‘regeneration’ project, might read the work as a resurgence of a popular socialist conscience (perhaps presciently as it happens).

So, billboards; collages; interventions on public transport that mimic the look of official signage; faux street signage; large paste-ups and more discreet scale posters that target governmental and corporate malfeasance such as Dr. D’s GCHQ Always Listening to our Customers and Primate Change Now. Carbon Addiction is Killing us works; oversized and witty, mock Community Chest and Chance cards left in the streets that draw comparison between what real life developers, planners, investors are ‘playing at’ and Monopoly, the board game that came to epitomize rampant acquisition and speculation (and usually cheating) even if its politically left leaning, anti-landlord origins sought to do quite the opposite. And that’s, as I’ve said, without even taking into account Dr. D’s numerous 3D interventions, his supplying of protest placards and generously assisting other visual activists to site their work innovatively in city streets. As Brighenti (2007: 333) has argued:

In the absence of dissonant messages, representations tend to settle down and stabilize themselves. That is why the issue of access to the places of visibility is a central political question. To access these places is the precondition for having a voice in the production of representations. More precisely, it is not simply ‘access’ that matters, but rather the styles and modes of access (Brighenti, 2007: 333).

It should be clear by now that Dr. D’s ongoing body of work operates on many levels. There’s righteous but often subtle indignation, wit and thoughtful provocation. And throughout, a dedication and persistance across so many styles and modes of urban intervention. The range of work and constant invention as to places of visibility stirs up and disrupts the tendency of dominant socio-political narratives to prevail unchallenged.

Before signing off with a change of tack I want to point out one further element to Dr. D’s practice. Many recognise the graphic invention and wit as well as his canny, pointed positioning of works. A feature that is less often remarked upon is the emotional charge his work can carry. I’m thinking of the giant ‘ransom note’ style interventions on billboards left blank by the outdoor advertising companies (Figure 10 and Figure 11).

Like much of Dr. D’s output, these gigantic epigrammatic works are an act of gifting that ‘brightens’ people’s day. ‘Gifts’ that are often remarked on and circulated via social media. They are archetypes of roadside distraction. But while these billboards could be said to be one-liner ‘shout outs’ at passersby, multiple connotations soon emerge.

With irregular letters culled from newspapers, the stencilled ransom note style works are at once comical – on account of their blatancy and scale, ransom notes are usually intimate or at least secretive communications – but there is also a melancholic desperation. It is not established whom exactly is Left sucking the mop again so perhaps this refers to a general malaise. Dr. D’s Wait here for further instructions billboard intervention seems similarly abject. Seeing this in the teeming environment, that ‘thick’ urban space as sociologists sometimes refer to it (Read, 2001), one mentally plays out the required act but soon enough it dawns on the viewer that even in the busiest of urban hubs, if we did as the billboard suggests, the likelihood of ‘rescue’ or that an offer of purposeful life chances might occur while you wait there is, well, zero.

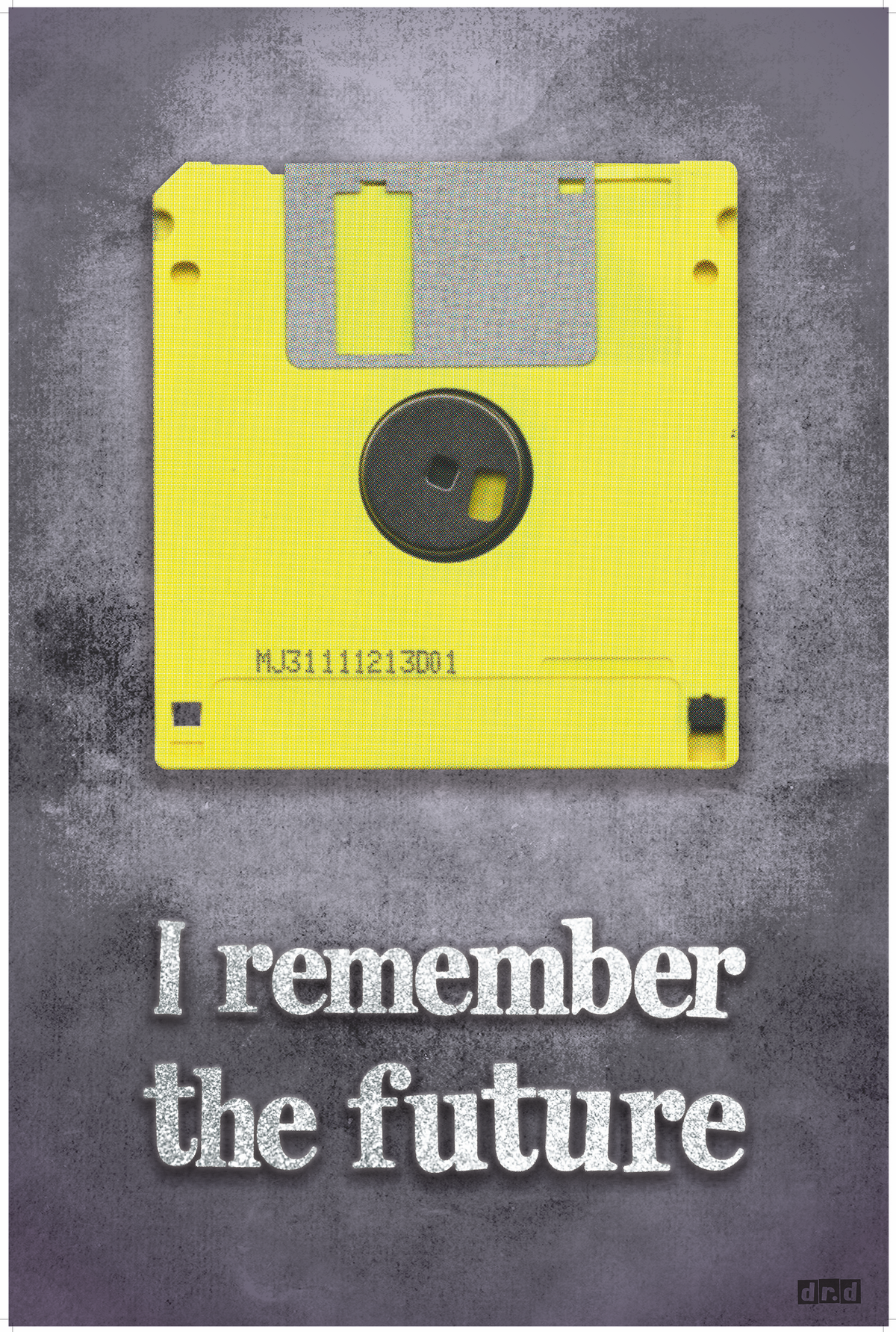

A more recent 2018 work showing a yellow floppy disc on a grubby, grey-violet background with the phrase beneath in ‘glittery’ silver type, I remember the future, is also emotionally charged (Figure 12, above). While the ransom note billboards suggest existential angst, I remember… challenges the positive trajectory of humankind whereby things can only get better. This is clearly not the case here in the UK and around the world. It’s perhaps not surprising that certain of Dr. D’s works seem riven with estrangement, disappointment and a palpable, gut-wrenching dolour.

To conclude, almost every example of Dr. D’s work referred to here so far presents as the sort of stuff many people could at least imagine themselves doing. There’s rarely any technical wizardry, but I’m going to wind up with a further strain of his visual activism that first requires a bit of context. In recent years, we’ve seen a significant shift by, in the US, Jordan Seiler’s PublicAdCampaign, and Art in Ad Places who have been hijacking NY phone kiosk ad spaces and installing artwork. The work of Special Patrol Group, smart and radical publications by Dog Section Press here in the UK and globally Brandalism has, of course, coordinated some brilliant interventions. Recently legallyblack and the advocacyacademy had some incisive work installed in Brixton regarding the visibility of the BAME community in film. The shift to more militant, progressive and/or anti-consumerist interventions on commercial advertising space usually monopolised by corporate entities is flourishing.

What particularly interests me in this regard with Dr. D’s work is when his interventions mimic the visual language of adverts or, in the case of his Curfew posters, municipal signage (Figure 13). There’s still wit – this work plays on the ‘Congestion Charge’ in London – but as these works wear the ‘livery’ of officialdom they pass under the radar, rather than sticking out like a sore thumb, and to even read them as oppositional can take a second or third glance.

The spectacle, populist media, policing and right leaning policy all cohere to manage a supposed ‘democratic’ society in its own image. With Curfew, the ‘content’ and surreptitious physical form of the work reiterates the passers-by’s lack of access and agency. Mimicry of the visual languages of authority and its revelation to be false, mocking and/or questionable interrupts prevailing messages of social control. They prompt both mirth and an uneasy feeling that we’re constantly being micro-managed. And the fact that publics are first induced to ignore or rather not see such works (who reads a notice we think we’ve already seen a thousand times?) makes the eventual realization that they do not belong all the more subversive.

It is the way such interventions query our constant subjection to behavioural and other boundaries that constitutes their valuable work of dissent. Long before Owen Jones sought to expose the consequences of our ‘Because I’m Worth It Culture’ and how ‘an ever more unequal distribution of wealth leaves those in power with the feeling that they have every right to ever greater slices of it.’ Dr. D had ‘re-presented’ the L’Oreal advert as N’Oreal (Figure 14).

Hair from India. Voice via auto tune. Publicity by Satan. A key feature of this vein of work is how Dr. D is apparently seeking to be more thoroughly ‘woven into’ the urban fabric rather than stamped on to its surface. Also, with N’Oreal, in part the point is that we absorb the image, and take it for granted, pretty much as we would any ‘pleasing’ example of the advertisers’ seductive (normative) handiwork. Clocking visual activism in official ad sites can lend them a sort of delayed impetus that contributes to their effect. These works remind us that our lives are continually filtered, mediated, trammeled: be that by personal earphones, screens, ‘happy’ pills, endless exhortations to consume and, at the same time, to do as we are told. All this becomes who we are: a society driven more and more by the prerogatives of the market economy.

The urban spectacle would have us believe that its overriding character is, yes aspirational, but emphatically neutral and apolitical: that generally we’re going to be just fine if we carry on pretty much as we are. Dr. D’s pithy interventions, highlighting so many germane issues and employing such a wide variety of modes of address, repeatedly suggest otherwise (Figure 15).

Adrian Burnham has a long held empirical interest in both the variety and efficacy of interventions on urban space and a particular fascination with paper-based art and visual activism. His career spans both a mundane engagement with the metropolis – as a commercial flyposter in the 1980s and 90s – to more academic study of the city and the social production of space at Goldsmiths University. After 10 years leading courses and lecturing on art and design at Hackney Community College, in June 2016 he founded and continues to curate www.flyingleaps.co.uk: a street display and online platform for socio-politically engaged artists. He regularly writes about and gives talks on art and urban culture.

Easterling, K. (2014) Extrastatecraft. London: Verso.

Brighenti, A. (2007) Visibility: A Category for the Social Sciences. Current Sociology, 55(3): 323-342.

Read, S. (2001) ‘Thick’ Urban Space: Shape, Scale and the Articulation of ‘the Urban’ in an inner-city neighbourhood of Amsterdam, Proceedings of the 3rd International Space Syntax Symposium, Georgia Institute of Technology.