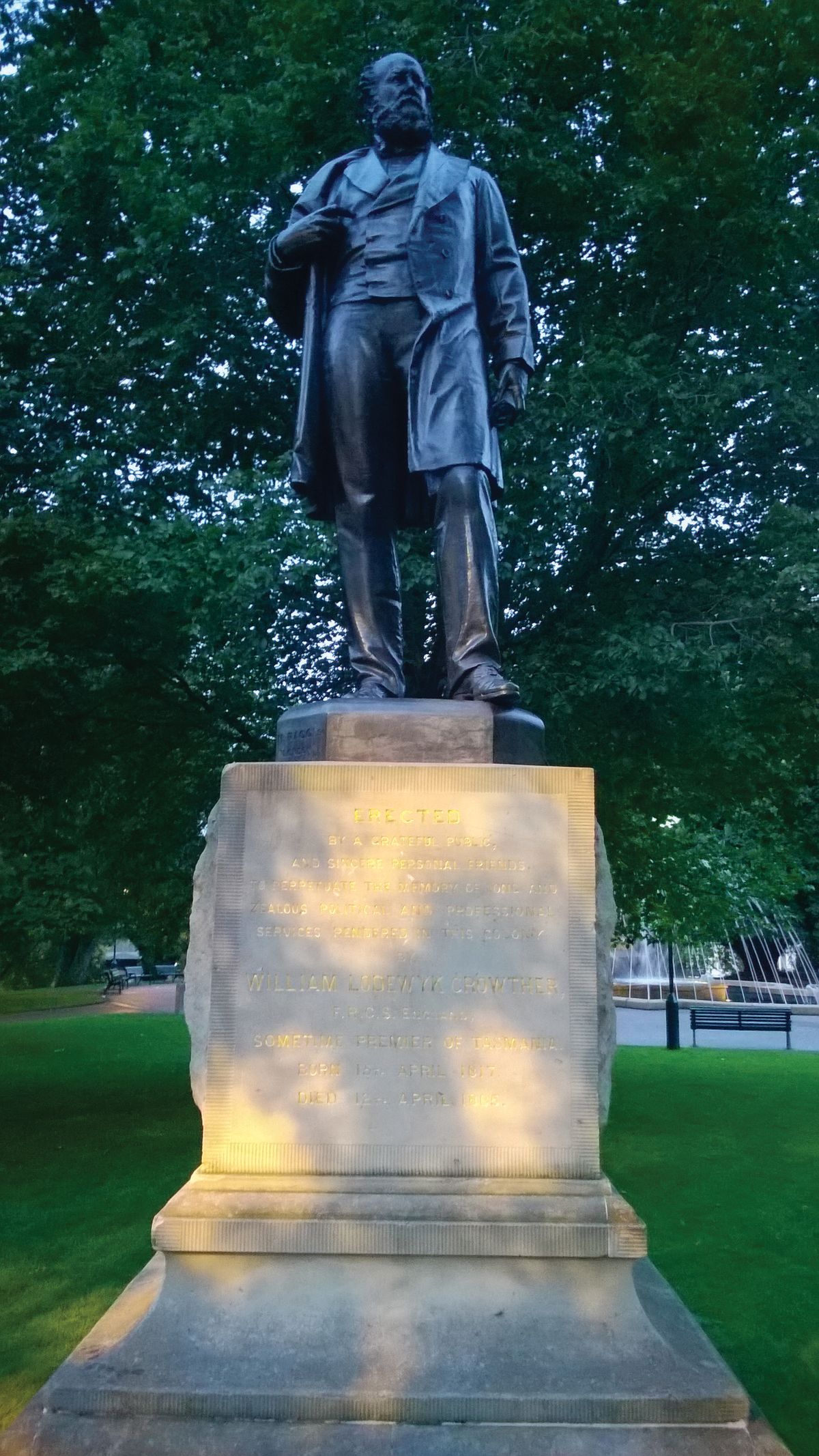

The expansion of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 shone a spotlight on global anti-racist protests not seen since the anti-apartheid movement in the early 1980s. Powerful images of the contestation and removal of statues of historical figures linked to violence, colonialism, and slavery were broadcast widely by the media. Three years on, Confederate statues in the US and colonial monuments in Australia, to name just two cases, continue to receive critique, yet with mixed outcomes. While US citizens and governments have demonstrated a certain amount of political will in removing symbols of white supremacy from public space, Australia has done little to dismantle its racist symbols and the laws protecting them. Hobart City Council’s recent decommission of a statue of William Crowther (Figure 1) is so far the only instance of permanent government-sanctioned removal in Australia motivated by principles of historical justice. A surgeon and later Premier of Tasmania, Crowther decapitated and stole the remains of Aboriginal man William Lanne. Yet, as historian Cassandra Pybus has argued, tributes to perpetrators of even more heinous deeds remain standing across the nation (quoted in Murray, 2022).

As researchers with expertise in law, history, and the creative industries, in late 2020 we commenced a research project that analyses the nature and effect of the laws that restrict and regulate engagements with these contested public artworks. Our research focuses on how the moral rights held by statue artists can conflict with the public interest in the conversations around racial justice that anti-racist graffiti stimulates. As the project unfolded, we also experimented with practice-based methodologies in the commission and curation of protest art as a means of energising and supporting public discourse around law’s direct, indirect, and symbolic maintenance of racist public spaces. One of our key findings is that both unlawful and lawful protest art are powerful conversation-starters that support critical reflection on contested public art as a legal object and site of in/justice. Our study encompassed both ‘illegal’ anti-racist graffiti on contested statues and ‘legal’ artwork critical of law’s role in perpetuating colonial injustice.

The meaning of contested statues

First Nations opinions diverge about what should be done about contested statues (see Baker, 2020; Carlson & Farrelly, 2023), as do those of philosophers (Bell, 2021; Scarbrough, 2020; Shahvisi, 2021) and historians (Barlass & Gladstone, 2022; Dwyer, 2020). Yet, there is general agreement that contested statues are powerful symbols of oppression and problematic representations of history and public memory. Nathan Moran, CEO at Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council and a Goori man, states that such statues ‘glorify colonisation’ (quoted in Baker, 2020). Aileen Moreton-Robinson, a Goenpul woman from Minjerribah and the Quandamooka First Nation, argues that their continued presence shows that ‘dead white male bodies will be remembered and dead Indigenous bodies will be forgotten’ (2022: 67).

For these reasons, some activists have taken matters into their own hands and graffitied contested statues with anti-racist slogans and imagery. For example, in June 2020, political activist Peter John Wright painted red hands on a statue of Robert Towns (Figure 2) and wrote ‘slave trader’ on the accompanying plaque. He did so in protest of Towns’s links with Queensland’s slaving history (‘blackbirding’) and called the placement of the statue in Townsville’s central business district ‘a stain on the moral conscious [sic] of this town’ (quoted in Chomicki, 2020). Most recently on Anzac Day, a national public holiday for commemorating veterans, a statue of Major General Lachlan Macquarie, New South Wales governor between 1810 and 1821, was smeared with red paint, handprints, and inscribed with the phrases ‘no pride in genocide’ and ‘here stands a mass murdered [sic] who ordered the genocide’ in protest of Macquarie’s ordering of his soldiers to kill and capture Indigenous Australians during the frontier wars (Sharma, 2023).

Conceived of as a form of art, this protest action visually depicts what justice looks like to a segment of the community. Whether or not the graffiti is supported by those who encounter it, painting over a statue of a perpetrator of historical injustice is an act of personal agency and resistance to the status quo that sparks conversation. Yet, as a decolonial strategy the impact and message of such activism involving contested statues is stifled by a multiplicity of laws.

Law and anti-racist graffiti

The threat of sanctions has an unequal cooling effect on the defacement of statues. It is notable, for example, that Wright and others are not themselves Indigenous and, as such, may enjoy a certain immunity to the prejudice and brutality that Indigenous breakers of white laws are so often subjected to. For some activists, the public notoriety of statue graffiti is part of its appeal; the media sensation it provokes captures attention for the political cause (Gamboni, 2018). While the responsibility for ridding Australia of racist monuments may justifiably fall on European settlers, others have questioned why progressive white Australians have taken till now to show any commitment (Carlson & Farrelly, 2023; Mokak, 2020). Conservative interests in defending colonial heritage sites have not afforded the same protection to sacred Aboriginal sites, reflecting the exclusion of Indigenous and minority communities typical in international law (Lixinski, 2019).

In its graffiti form, anti-racist protest is highly regulated. Multiple laws prohibit activist activities involving public artworks, and these laws can directly, indirectly, or symbolically devalue political speech. Graffiti is a form of property damage under criminal law (Hadley et al., 2022: 5). Peter John Wright, for example, was convicted of wilful damage per the Criminal Code 1899 (Qld) s. 469 and fined $AUD500 plus a cleaning fee for his graffiti on the Towns statue. Less well known is that heritage law can also protect contested statues from activism such as defacement or removal (Lixinski, 2021), and when a statue is within the copyright term, intellectual property law can also protect contested statues from interference. The contested statues mentioned above of Towns and Macquarie, were created by artists Jane Hawkins and Frederic Marie René Chapeaux, and dedicated in 2005 and 1994, respectively, and both are within the copyright duration of the authors’ life plus seventy years (Copyright Act 1968 [Cth] s. 35).

With regards to the intellectual property implications, while vandalism is not generally a copyright infringement, it can be a moral rights infringement (Hadley, Hook & Orr, 2022: 19-23). Like most common law countries, Australia has a moral rights regime predicated on Article 6bis of the 1886 Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works (as revised 1928) that requires the protection of authors’ moral rights of attribution and integrity. These types of rights can be found in jurisdictions across the world with most adopting at least three rights: the right of attribution, the right against false attribution, and the right of integrity (Davies & Garnett, 2016: 4) that come into being when copyright works are created. The US is an outlier in that it only has moral rights for visual artists.

In our research, we have focussed on the moral right of integrity because it is the right that gives absolute control over a work to the creator. It is a right granted to authors of copyright works, including statues as a type of artistic work, to protect their honour and reputation from the ‘derogatory treatment’ of their works, including distortion, mutilation, destruction, and alteration (Copyright Act s. 195AK). As a form of both alteration and mutilation, the defacement of a statue through the application of graffiti clearly amounts to a derogatory treatment and falls within this category of infringement. This means that when a contested statue is within the copyright term, the statue artist’s interest in the integrity of the artwork they create (and their feelings towards it) is valued above all other considerations – regardless of whether the art is racist or depicts a historical figure associated with colonialism, slavery, or violence. Neither the ‘community’ nor the ‘public’, as groups that are potentially affected or enriched by anti-racist dialogue, are recognised as stakeholders in moral rights law.

The problem with moral rights

Moral rights protect a very specific, and contested, view of creativity and originality. They are a civil law concept that come from the Romantic idea that an author’s personality is enshrined within a work, so that when a work is interfered with, then the reputation of the author is prejudiced (Aide, 1990). In other words, you cannot separate the art from the artist as they share a sacred bond that should not be interfered with. For example, in Canada, a statue within a mall was decorated with Christmas paraphernalia. The statue’s artist successfully applied for an injunction to stop this from occurring as they believed it prejudiced their reputation to have their artwork treated so (Snow v Eaton Shopping Centre (1982) 73 CPR (2d) 204). Moral rights also rely on an assumption that all works stem from the personality of an artist, even commissioned works of busts of historical figures where there may be artistic direction from third parties that limit the artist’s aesthetic choices.

In safeguarding the expression of the creator, moral rights can sometimes conflict with user rights and free speech. While the right of integrity can protect creators from having their characters used in fan fiction, their music from being played at a political rally they disagree with, or their work from being hung inappropriately at a gallery, it also puts the creator’s freedom of expression above the freedom of speech of others – including activists who may object to racist messages, themes, or the deeds of an individual depicted in the work. While there has been very little litigation around moral rights, especially in civil law countries, they still create a barrier to protest, critique, and engagement. This is especially the case for public art, for which citizens have little say over its installation – or continued presence – in the spaces they inhabit.

Reforming moral rights

The fact that doing anything to a contested statue, including painting on it, can trigger a moral rights claim, runs counter to the sense of belonging that public art is meant to represent and reflect. It is also inconsistent with other provisions in Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, specifically ss. 65–68, that explicitly recognise the right to enjoy the physical commons by permitting some two-dimensional engagements (i.e. making a painting or a sketch, taking a photograph) with public art that would otherwise amount to copyright infringement. Moral rights law, as currently framed, sends a message that racial justice is not a priority in our public spaces.

Public spaces should be democratic spaces that foster, rather than shut down, dialogue around the place and purpose of contested statues. Three possibilities for moral rights reform include mandating political speech as a factor to consider when assessing the defence of reasonableness to moral rights infringement; introducing a designated public art exception to moral rights infringement; and investigating whether the moral rights regime unduly burdens the freedom of political communication (Hadley, Hook & Orr, 2022: 24–26). Under the latter option – our preferred option – a moral rights infringement would still take place following the application of anti-racist graffiti to a statue, but the statue artist’s moral rights would be curtailed when the democratic benefits of engagement with public art carries greater weight. In this way, the value of the contribution of the graffiti to anti-racist dialogue could trump a statue artist’s rights in appropriate circumstances.

There is no recalibration of moral rights law currently on the horizon. In these circumstances, we have considered other means of supporting anti-racist dialogue, looking to the communicative potential of lawful protest art.

Figure 3. Entropy Awakening, 2022. ©Travis De Vries. Reproduced by permission of the artist.

Figure 3. Entropy Awakening, 2022. ©Travis De Vries. Reproduced by permission of the artist.Protest art and anti-racist dialogue

In 2021, one of our authors, Marie Hadley, commissioned First Nations artist Travis De Vries, who has Gamilaroi and Dharug kinship, to create an artwork that reflects on the conflict between the moral rights of the artists and the rights of the public when it comes to contested statues. The commission was open-ended, asking De Vries to create a digital artwork in response to one of our research papers (Hadley, Hook & Orr, 2022) and to document his creative process. The resulting artwork, Entropy Awakening (Figure 3), was featured in an eponymous exhibition of De Vries’ protest-adjacent workat 107 Projects in Sydney in October 2022. Hadley also used the artwork to teach ‘Critical Perspectives on Copyright Law’ to a cohort of University of Newcastle students in 2022.

We tracked the impact of Entropy Awakening through a variety of qualitative methods (surveys; semi-structured interviews; university coursework data including discussion posts and assessment responses; critical reflections) and with a variety of stakeholders including exhibition attendees, university students, the researchers who participated in the exhibition (Hadley, Manning & Wright) and the artist himself (De Vries). A snapshot of the research with the students highlights the impact of this artwork in supporting interrogation of the relationship between art, law, and justice. Forty-seven out of 121 students in the ‘Intellectual Property Law’ cohort (2022) participated in the study.

Law students experienced Entropy Awakening as ‘haunting and dark’; ‘mesmerising’ but with a ‘sinister edge’; ‘beautiful … [yet] deeply disturbing’. The imagery of the suns, moons, and scales of justice indicated law’s failure to adapt or change over time; ‘the law … protect[s] its racist foundations’. The blood in the scales was felt to be a powerful representation of intergenerational trauma or that access to justice is a farce; law as ‘a tool of concealing, managing, and relocating power away from non-western cultures’.

Despite these strong critiques of ‘the duplicity of the figure of Lady Justice’, many law students also read hope in the work. The largest statue’s breaking point – its disintegration – indicated the possibility of a more equitable future. To them, Entropy Awakening depicted a ‘world awaiting radical change’, an image of a world of First Nations sovereignty that De Vries wants all of us to see.

Dr Marie Hadley is a Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Newcastle, Australia; Dr Sarah Hook is a Senior Lecturer in Law at the Western Sydney University, Australia;

Dr Sarah Hook is a Senior Lecturer in Law at the Western Sydney University, Australia;

Nikolas Orr is an art history and transnational history scholar and PhD candidate at the Centre for the Study of Violence, University of Newcastle, Australia;

Adam Manning (Kamilaroi) is a musician and artist and Associate Lecturer in the School of Humanities, Creative Industries and Social Science at the University of Newcastle, Australia;

Dr Rewa Wright (Ngāi Tawake/Te Kaimaroke/Te Uri o Hau hapu of Aotearoa/New Zealand) is a Senior Lecturer in Creative Practice (Film, Screen and Animation) at the Queensland University of Technology, Australia. The authors thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

- 1

Information about the exhibition can be accessed at https://mariehadley.com/entropy_awakening.

- 2

The syllabus for this teaching module can be accessed at https://mariehadley.com/resources

- 3

This project was carried out in accordance with University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Protocol H2021-0377.

- 4

Student 36, Discussion Board Post LAWS6086 Intellectual Property Law (March 26, 2022); Student 43, Discussion Board Post LAWS6086 Intellectual Property Law (March 26, 2022); Student 45, Discussion Board Post LAWS6086 Intellectual Property Law (March 27, 2022).

- 5

Student 21, Discussion Board Post LAWS6086 Intellectual Property Law (March 23, 2022).

- 6

Student 1, Discussion Board Post LAWS6086 Intellectual Property Law (March 17, 2022).

- 7

Student 10, Discussion Board Post LAWS6086 (March 26, 2022).

- 8

Student 44, Discussion Board Post LAWS6086 Intellectual Property Law (March 28, 2022).

- 9

Student 18, Discussion Board Post LAWS6086 (March 26, 2022); Student 13, Discussion Board Post LAWS6086 (March 23, 2022).

Aide, C. (1990) ‘A More Comprehensive Soul: Romantic Conceptions of Authorship and the Common Law Doctrine of Moral Right’. University of Toronto Faculty of Law Review, 48(2): 211–28.

Baker, N. (2020) As ‘racist statues’ topple around the world, Australia is being urged to address its own monuments. SBS News, June 10, 2020. [Online] Accessed January 26, 2023. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/as-racist-statues-topple-around-the-world-australia-is-being-urged-to-address-its-own-monuments/g59pu67wy].

Barlass, T. and Gladstone, N. (2022) Future of all statues should be regularly assessed, historian says. Sydney Morning Herald, August 1, 2022. [Online] Accessed January 26, 2023. https://www.smh.com.au/national/future-of-all-statues-should-be-regularly-assessed-historian-says-20220725-p5b4bb.html.

Bell, M. (2021) ‘Against Simple Removal: A Defence of Defacement as a Response to Racist Monuments’. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 39(5): 778–792.

Carlson, B. & Farrelly, T. (2023) Monumental disruptions: Aboriginal people and colonial commemorations in so-called Australia. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Chomicki, C. (2020) ‘Townsville Man Fined for Vandalising Statue of Colonist Robert Towns by Painting ‘Blood on his Hands’’. ABC News, September 18, 2020. [Online] Accessed January 26, 2023 https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-18/robert-towns-statue-townsville-vandal-fined/12677876.

Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).

Davies, G. & Garnett, K. (eds.) (2016) Moral Rights. London: Thomson Reuters.

Dwyer, P. (2020) Transform statues to make us question the past. Sydney Morning Herald, June 15, 2020. [Online] Accessed January 26, 2023. https://www.smh.com.au/national/transform-statues-to-make-us-question-the-past-20200614-p552hd.html.

Gamboni, D. (2018) The Destruction of Art: Iconoclasm and Vandalism Since the French Revolution. Rev edn. London: Reaktion Books.

Hadley, M., Hook, S., Orr, N. & Jones, S. (2022) Briefing Paper ‘Anti-Racist Graffiti and Public Art Statues’. Newcastle: Centre for Law and Social Justice, 1-9. [Online] Accessed January 22, 2023. https://www.newcastle.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/799951/Marie-Hadley-Anti-Racist-Graffiti-and-Public-Statues-.pdf.

Hadley, M., Hook, S. & Orr, N. (2022) ‘Ideological Vandalism of Public Statues: Copyright, The Moral Right of Integrity and Racial Justice’. Griffith Journal of Law & Human Dignity, 9(2): 1–34.

Lixinski, L. (2021) ‘Punching Up or Down: International Law’s Fraught Relationship to History As Illustrated Through Cultural Heritage’. ILA Reporter, July 14, 2021. [Online] Accessed January 26, 2023.https://ilareporter.org.au/2021/07/punching-up-or-down-international-laws-fraught-relationship-to-history-as-illustrated-through-cultural-heritage-lucas-lixinski/.

Lixinski, L. (2019) International Heritage Law for Communities: Exclusion and Re-imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mokak, G. (2020) ‘Public memory: The role and curation of commemorative monuments and public art’. National Association for the Visual Arts, June 30, 2020. [Online] Accessed January 26, 2023. https://visualarts.net.au/news-opinion/2020/public-memory-role-and-curation-commemorative-monuments-and-public-art/.

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2022) ‘Monuments, Place Names and Black Lives Matter: Memorialising Captain James Cook’. Legalities, 2(1): 67–81.

Murray, W. (2022)Controversial William Crowther statue to be removed after Hobart City Council Vote’. ABC News, August 16, 2020. [Online] Accessed January 26, 2023. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-08-16/william-crowther-statue-to-be-removed/101334976.

Scarbrough, E. (2020) ‘Burying the Dead Monuments’. Aesthetics for Birds, June 18, 2020. [Online]Accessed January 26, 2023. https://aestheticsforbirds.com/2020/06/18/burying-the-dead-monuments/.

Shahvisi, A. (2021) ‘Colonial Monuments as Slurring Speech Acts’. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 55(3): 453–468.

Sharma, Y. (2023) ‘Vandals Deface Former British Army Officer’s Statue in Anzac Day Protest North-West of Sydney’. Sky News, April 25, 2023. [Online] Accessed April 28, 2023. https://www.skynews.com.au/australia-news/vandals-deface-former-british-army-officers-statue-in-anzac-day-protest-northwest-of-sydney/news-story/ee0bfc88774daadc00a26366829c5af5.

Snow v Eaton Shopping Centre (1982) 73 CPR (2d) 204.