Nuart Journal: It’s been 13 years since the publication of Trespass, which has since become almost as ubiquitous as Subway Art on bookshelves around the world – the Subway Art of Street Art. Trespass: A History of Uncommissioned Urban Art marks a particular moment in time. It was written before the rise of neo-muralism, and the global spread of street art festivals – not to mention the role of social media in how people encounter art on the streets. This is street art at the height of its subcultural moment. Your treatment of the Trespass theme has had considerable longevity in its impact, and we are curious to hear your contemporary take on this theme. So, this chat is intended as an opportunity to critically revisit the theme of Trespass, given all that has happened since you last took on this topic…

Carlo McCormick: Because Trespass came out so long ago, in the rapid, constantly changing face of art on the streets, it could probably use an update in many ways, except that I hate the publisher. But I was smart enough contractually to keep the intellectual property. The book is now a weird time capsule. It’s probably pretty dated. They wanted a book on street art, which was, at that point, new and bubbling. But I was really not very interested in telling that story. I knew it was a temporal story, and that it would date really quickly. So, in the premise that I took, I was thinking that we can’t tell the story of street art unless we put it in the context of graffiti and that history. And then we can’t really talk about graffiti unless we talk about all of the different ways that people address public space – so activism, and political graffiti. The first graffiti I saw as a kid was political. It wasn’t people’s names on the walls, it was someone saying something really wild. But a lot of political and socially engaged work has started becoming just ‘feel good’ messages writ large. And that stuff’s corny to me. It’s why, as much as I love the idea of community mural projects, they can get pretty cheesy. But great things can happen even in corny places.

I also wanted to include the aspects of the avant-garde that have also come up with performative and visual ways to address the streets. So, that was the concept, which I think still holds up. It’s the idea of the bigger conversation. I think we still need to continue to track all of those elements and not ghettoise culture by going, ‘Oh, I only care about the muralists at the moment’. The energies will always shift.

In the book, you discuss the etymology of the term trespass, tracing it from an earlier moral Biblical form to its contemporary legal sense. For those readers unfamiliar with this etymology, could you maybe expand on how this older sense of trespass as sin or transgression informs our contemporary understanding – and whether this still has anything to do with art on the streets?

‘Trespass’ was just a way of trying to collect as much diverse material as I could and to keep extending our ways of thinking about gestures in public space. As an art writer, I’m interested in mark making, and to understand and to read the phrases left behind. But I love the idea of urban explorers. A big part of their whole MO is to leave no trace, and if anything, to invade a space and make it a little nicer upon your leaving, like, if you find trash there, you remove it. And that’s beautiful. Conversely, I’m also interested in the more violent notion of the breach. A book that really influenced me as a kid was Crowds and Power by Elias Canetti – I think he wrote it in around 1960. It was a credible, comprehensive study about how crowds work and how power works. He talks about sporting arenas and churches, and all the ways in which people gather, and how these architectures of gathering can amplify or contain the energy of a crowd. But when you deal with a mob, the breach is actually the important thing. You can have a large group of people protesting, but the trigger is literally breaking the barricade, or quite typically someone throwing a brick through a window. That would be the breach. I’m really interested in that, and not necessarily in a positive way, because in the United States we just went through this with the insurrection of January 6th. I never thought I’d be defending the government. But it turns out Big Brother is not the worst relative in the world. Obviously, the last kind of political gesture from the left that was equivalent would have been Occupy, with the idea of occupying space. All these are different strategies with different dynamics, each contending with the little space left for us that is not privatised.

Editor-in-Chief Martyn Reed’s initial inspiration for the theme of Trespass came from Nick Hayes’ The Book of Trespass which reveals a long story of enclosure, gifting of land, exploitation, and dispossession of public rights and the commons. Martyn sees parallels here with street art and graffiti and their relationship to property rights, but also with urban art’s ‘trespass’ into fields such as public art and the art establishment. Hayes sees our ‘quasi-religious belief in the sanctity of private space as the dark heart’ of the UK. He considers trespass as an act of solidarity – and the real value of trespass as not so much in the thrill of transgression, but the effect this has cumulatively in lifting the spell of private ownership.

I like the way Hayes talks about property as the spell, and how do we break the spell of private ownership? Because it becomes a consensus reality that a bunch of people grabbed a bunch of land that at one point belonged to no one and to everyone – and how do we settle it? But I’m an urbanist. I don’t hate nature – we all love to be out in the fresh air and smelling something other than fucking garbage – but it’s not my milieu. If I have to think of nature, I still think of it within the city, I think back to the beginning of the Guerrilla Gardening movement in the 1970s, where they were taking condoms and filling them with seeds and fertiliser.

I shared with Martyn, Agnes Denes’ work ‘AConfrontation’ where she grew a wheat field in Manhattan – that was a great moment. That was kind of a land reclamation, upon which we could build Battery Park City and the World Trade Centre. Because when you create a massive landfill on that scale, and you’re no longer working on bedrock, you have to let it settle for many years before it’s stable enough to build on. There used to be a place on the same site called Art on the Beach. I used to love to break in late at night with girls as a kid. So, I’m interested in those things. But the community garden movement is up there with community murals. It’s great for the community, but it’s maybe not the most edgy, visually compelling work.

Another interesting thing from The Book of Trespass is that Hayes is both an artist and a writer – he does his own illustrations for the book. And he notes that the very act of sketching may ‘legitimise loitering’ – which meant he was often not challenged when trespassing. I wonder whether sketching on walls may also now, in 2023, paradoxically legitimise loitering, or nullify an act of trespass? Has this once transgressive act become so benign that we no longer see this as an act of trespass?

Yes. It’s always worked that way. There was a book I was involved in years ago that came out in Germany, Legal/Illegal. It’s really obscure now, but it had a big impact then. And one of the things I was thinking at that time was that I’ve seen a lot of people do really out there stuff on the street and get arrested for it. They’d go before the judge, and say, ‘well, I’m an artist.’ That was performance art that offended people’s nudity laws or broke other laws – like trespass or illegal congregation. Generally, for prosecutors and judges, art’s a fucking riddle – it intimidates most people. And unless they’re really knee jerk and anti-art – which you’re not going to get in a place like New York City – they’re going to say, ‘Oh, it’s art – just get out of here and don’t do it again’. And it’s really great when art becomes kind of a good excuse – a good alibi. But I also think that there’s a lack of responsibility in that. When you say, ‘Oh, it’s just art’, you’re saying, ‘It is just art’ – nothing more. You’re taking away whatever agency that intervention and illegality carries. If it’s going to spare you jail time or fines, you should probably pull this defence, but understand that you’re diminishing the force of your work by saying, ‘It’s just art’.

You describe creative acts of trespass, in your introduction to the book, as a provocation for others to question consensus reality. But I guess, if you’re using art as an excuse, then that provocation ceases?

With art, people’s eyes have a way of glazing over. When it comes to art, viewers get blinkered in the same way as when they’re faced with advertising. I do like people who do things that are not evidently one or the other. It’s almost like a quaint modernist notion of novelty to try to carry this into the 21st century. That’s why people like being tourists – because they actually start looking around – you can always tell who’s a tourist in New York, because they’re looking up at all the buildings, they’re more aware – but most people usually walk through their quotidian existence without paying much attention to anything. So, anytime you do something that misfits within that visual landscape and makes people wonder for a minute, I think you wake them up a little bit. There’s something positive about that. Even if they dismiss it and forget it, at least you momentarily rattle their cage.

There was this one group that were sending people to help people cross the street because they were all too busy looking at their cell phones. Helping people on corners so that they could keep on their cell phones. With screen time people are becoming even less conscious and less aware of their environment.

Alison Young has written a lot about our shared belief in public space being an illusion. She notes that a lot of the urban spaces that we think of as public, and as ours, are in fact a grid of privately owned spaces. And any unsolicited art in public space is in reality on private walls. So, art on the streets may feed our sense of common ownership, and our sense that we have a right to the city. But maybe that’s not really true?

Obviously, property owners are the vested interest – all those walls are someone’s property – the skin, the membrane, around public space. I’ve always loved things which really make you look where you walk. There’s been a whole lot of work done on sidewalks, on streets, on crosswalks, on floors. And that’s also illegal. You’re not really allowed to mark make there, you can still get arrested for doing a stencil on a sidewalk. I keep big files of jpegs on so many subjects and this is one of them. Municipalities started getting interested in these things, which start as illegal, artsy gestures, but then they employ artists to design crosswalks to be colourful, instead of just white lines, and people begin doing things with manhole covers, fire hydrants, and all that stuff we might call urban ornamentation. It’s one of the many cul-de-sacs I’m interested in. I’m not sure if it’s a medium or a genre, but it’s definitely one of the many strategies out there. So, is public space a kind of delusion? Perhaps insofar as the sanctity of walls, but as a kind of common ground we must all navigate it is as physical and material as it is hypothetical.

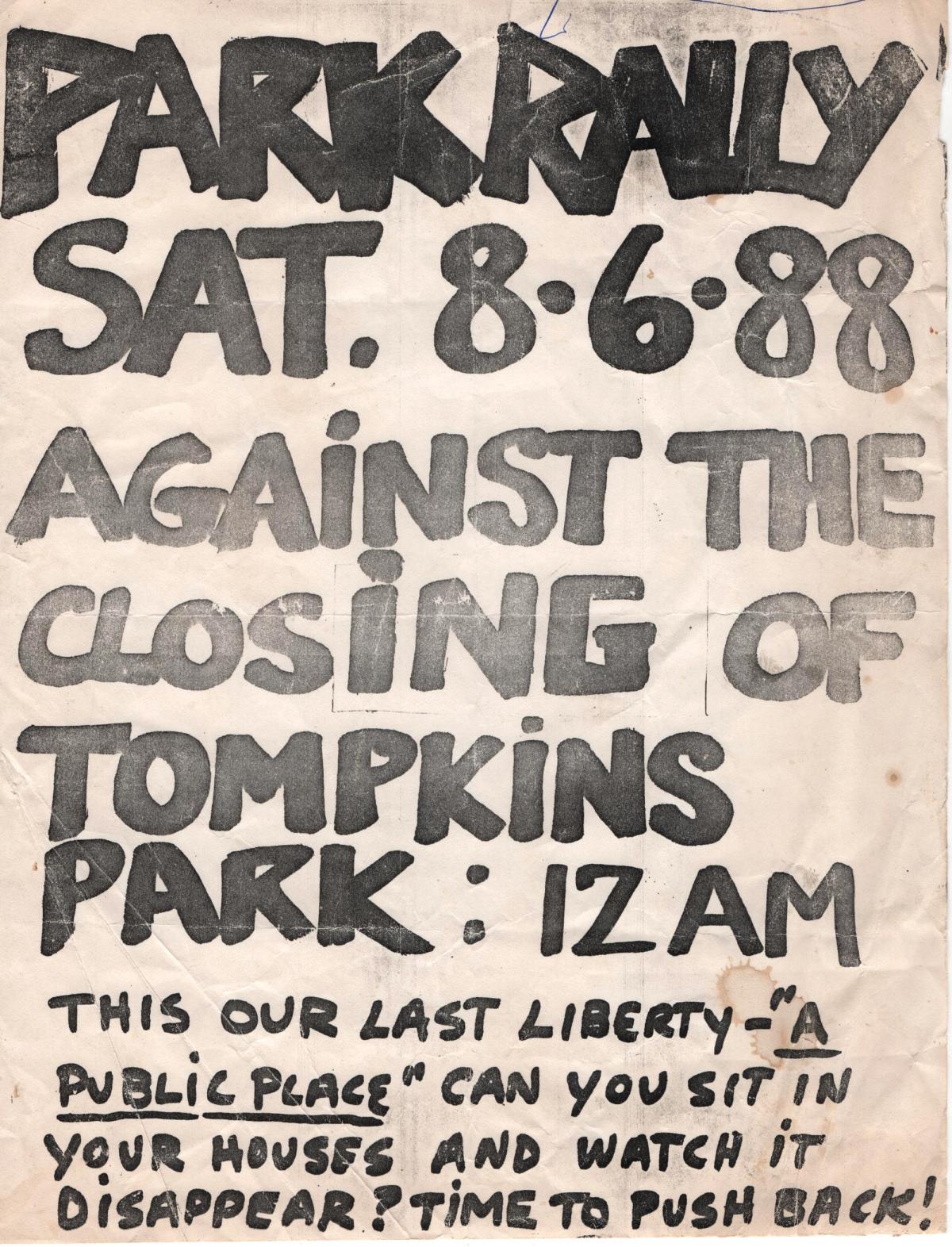

The idea of public space is ultimately a negotiation. It’s a social contract. For example, parks have social rules. Because they should be for everyone. So, you shouldn’t be in a trench coat masturbating near the children’s playground. It wouldn’t be appropriate. But in New York, in my neighbourhood, one of the biggest political events of the last many decades was the riots at Tompkins Square Park (1988) because the police were removing all the homeless people from the park. The police came in there and beat the shit out of everyone. It was a horrible crime, but I was very much on the outside of the discourse of my community, because while I empathise with and want real justice for homeless people, I didn’t like homeless people taking over the whole park. I didn’t want them to be the only people there. Beyond the fact that it turned into an open sewer and it smelled of human faeces, it’s simply that parks should be for everyone. There should be a solution to the situation of the unhoused, but you can’t take the parks away from the little kids who want to play there. And you can’t take them away from the old people who want to sit there, or from the young couples who want to cuddle up there. Parks have to be for everyone. Because there was this crisis in homelessness, and all these great social inequities, people thought I was a fucking asshole for saying that these camps had to go, but for me it’s because I love parks, precisely for their democracy and inclusion, that I hate to see them function solely as a release valve for the margins.

In the book, you describe unsanctioned urban art as ‘the problem child of cultural expression, the last outlaw of visual disciplines.’ More than a decade later, given the endemic rise of commissioned murals in creative cities, internationally, are unsanctioned forms of art in public space still remotely transgressive?

Well, certainly commissioned murals and placemaking are not transgressive. But yesterday, the building next to me was knocked down. And what made me so happy was seeing these super cute kids, they must have been like, 13-14 years old, climbing up, around, and over this big wall to get into the vacant lot. One of them scaled the thing and then the other one threw him the backpack filled with paint, and then climbed over after him, and I was like, ‘Oh, that’s fucking great’. Kids being kids and exploring. They’re not reinventing the wheel, maybe their work will be totally like toys. I have no idea, but they were fucking doing it. It’s still great. So, yes, trespass still has that power. But it really is for that age group.

I know plenty of 50-year olds who still break into places.

It’s like tattoos or potato chips. You can’t stop.

I have 17 tattoos now. I’m trying to stop.

That endorphin kick becomes addictive. Invader is always telling me, ‘You know what, I shouldn’t do this anymore. I get in trouble. And I make a very good career off my art, but I can’t help myself. I need to do it.’ And he does it prolifically. It’s like, ‘Yeah, man, you’re clearly addicted to it’. These practices are a form of engagement and a way of seeing – for whatever their ills they seem far preferable to disengagement and not looking.

Carlo McCormick is a critic and curator based in New York City. His writing has appeared in numerous magazines, hundreds of books, and over a dozen different languages. He has curated exhibitions at museums around the world and lectures regularly at universities, art schools, and other institutions.